December 17.

St. Olympias, A. D. 410. St. Begga, Abbess, A. D. 698.

[Oxford Term ends.]

The Season.By this time all good housewives, with an eye to Christmas, have laid in their stores for the coming festivities. Their mincemeat has been made long ago, and they begin to inquire, with some anxiety, concerning the state of the poultry market, and especially the price of prime roasting beef.

"O the roast beef of old England,

And O the old English roast beef!"

Manner of Roasting Beef anciently.

A correspondent, who was somewhat ruffled in the dog-days by suggestions for preventing hydrophobia, let his wrath go down before the dog-star; and in calm good nature he communicates a pleasant anecdote or two, which, at this time, may be deemed acceptable.

To the Editor of the Every-Day Book.Dear Sir,

As an owner of that useful class of animals, dogs, I could not but a little startle at the severity you cast on their owners in your "Sirius," or dog-star of July 3d. In enumerating their different qualities and prescribing substitutes, you forgot one of the most laborious employments formerly assigned to a species of dogs with long backs and short legs, called "Turnspits."The mode of teaching them their business was more summary than humane: the dog was put in a wheel, and a burning coal with him; he could not stop without burning his legs, and so was kept upon the full gallop. These dogs were by no means fond of their profession; it was indeed hard work to run in a wheel for two or three hours, turning a piece of meat which was twice their own weight. As the season for roasting meat is fast approaching, perhaps you can find a corner in your Every-Day Book for the insertion of a most extraordinary circumstance, relative to these curs, which took place many years ago at Bath.

It is recorded, that a party of young wags hired the chairmen on Saturday night to steal all the turnspits in the town, and lock them up till the following evening. Accordingly on Sunday, when every body desires roast meat for dinner, all the cooks were to be seen in the streets,—"Pray have you seen our Chloe?" says one. "Why," replies the other, "I was coming to ask you if you had seen our Pompey;" up came a third while they were talking, to inquire for her Toby,—and there was no roast meat in Bath that day. It is recorded, also, of these dogs in this city, that one Sunday, when they had as usual followed their mistresses to church, the lesson for the day happened to be that chapter in Ezekiel, wherein the self-moving chariots are described. When first the word "wheel" was pronounced, all the curs pricked up their ears in alarm; at the second wheel they set up a doleful howl; and when the dreaded word was uttered a third time, every one of them scampered out of church, as fast as he could, with his tail between his legs.

Nov. 25, 1825. JOHN FOSTER.

A real EVERY-DAY English Dialogue.

(From the Examiner.)

A. (Advancing) "How d'ye do, Brooks?

B. "Very well, thank'ee; how do you do?"

A. "Very well, thank'ee; is Mrs. Brooks well?"

B. "Very well, I'm much obliged t'ye. Mrs. Adams and the children are well, I hope?"

A. "Quite well, thank'ee."

(A pause.)

B. "Rather pleasant weather to-day."

A. "Yes, but it was cold in the morning."

B. "Yes, but we must expect that at this time o'year."

(Another pause,—neckcloth twisted and switch twirled.)

A. "Seen Smith lately?"

B. "No,—I can't say I have—but I have seen Thompson."

A. "Indeed—how is he?"

B. "Very well, thank'ee."

A. "I'm glad of it. — Well, —good morning."

B. "Good morning."

Here it is always observed that the speakers, having taken leave, walk faster than usual for some hundred yards.

Wild Fowl Shooting in France.Or where the Northern ocean, in vast whirls

Boils round the naked melancholy isles

Of farthest Thulè, and th' Atlantic surge

Pours in among the stormy Hebrides;

Who can recount what transmigrations there

Are annual made? what nations come and go?

And how the living clouds on clouds arise?

Infinite wings till all the plume-dark air

And rude, resounding shore, are one wild cry.Thomson.

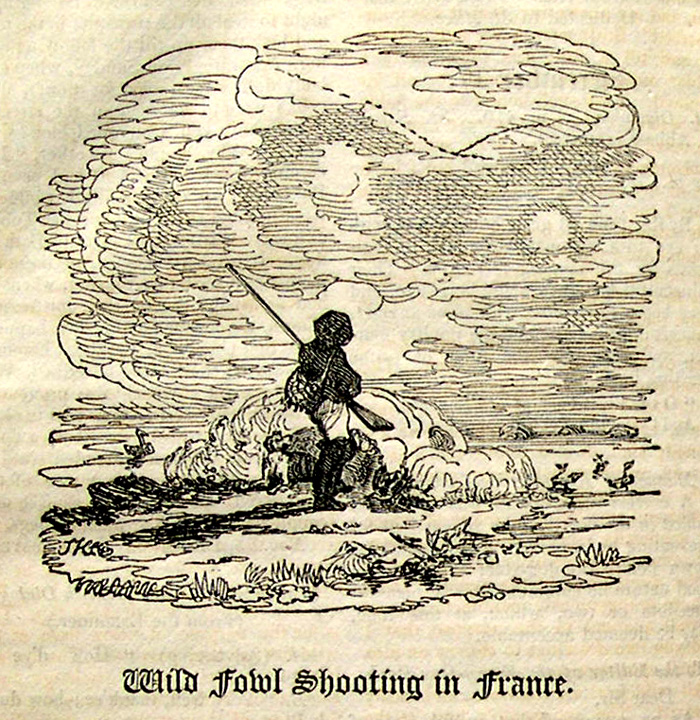

To a sporting friend, the editor is indebted for the seasonable information in the accompanying letter, and the drawings of the present engravings.Abbeville, Nov. 14, 1825.

Dear Sir,

It is of all things in the world the most unpleasant to write about nothing, when one knows a letter with something is expected. It is true that I promised to look out for pious chansons, miraculous stories, and other whims and wonders of the French vulgar; and though I do not send you a budget of these gallimaufry odds and ends, whereon I know you have set your heart, yet I hope you will believe that I thoroughly determined to keep my word. To be frank, I had no sooner landed, than desire came over me to reach my domicile at this place as fast as possible, and get at my old field-sports. I therefore posted hither without delay, and, having my gun once more in my hand, have been up every morning with the lark, lark shooting, and letting fly at all that flies—my conscience flying and flapping my face at every recollection of my engagement to you. I well remember your telling me I should forget you, and my answering, that it was "impossible!" Birds were never more plentiful, and till a frost sets them off to a milder atmosphere, I cannot be off for England. I am spell-bound to the fields and waters. Do not, however, be disheartened; I hope yet to do something handsome for your "hobby," but I have one of my own, and I must ride him while I can.It strikes me, however, that I can communicate something in my way, that will interest some readers of the Every-Day Book, if you think proper to lay it before them.

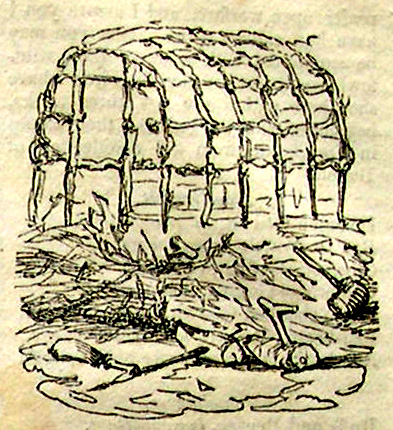

Every labouring man in France has a right to sport, and keeps a gun. The consequence of this is, that from the middle of October, or the beginning of this month, vast quantities of wild-fowl are annually shot in and about the fens of Picardy, whither they resort principally in the night, to feed along the different ditches and small ponds, many of which are artificially contrived with one, two, and sometimes three little huts, according to the dimensions of the pond. These huts are so ingeniously manufactured, and so well adapted to the purpose, that I send you two drawings to convey an idea of their construction.

All wild-fowl are timorous, and easily deceived. The sportsman's huts, to the number of eight or ten, are placed in such a situation, that not until too late do the birds discover the deception, and the destruction which, under cover, the fowlers deal among them. To allure them from their heights, two or three tame ducks, properly secured to stones near the huts, keep up an incessant quacking during the greater part of the night. The huts are sufficiently large to admit two men and a dog; one man keeps watch while his companion sleeps half the night, when, for the remainder, it becomes his turn to watch and relieve the other. They have blankets, a mattress, and suitable conveniences, for passing night after night obscured in their artificial caverns, and exposed to unwholesome damps and fogs. The huts are formed in the following manner:—A piece of ground is raised sufficiently high to protect the fowler from the wet ground, upon which is placed the frame of the temporary edifice. This is mostly made of ozier, firmly interwoven, as in this sketch.

This frame is covered with dry reeds, and well plastered with mud or clay, to the thickness of about four inches, upon which is placed, very neatly, layers of turf, so that the whole, at a little distance, looks like a mound of verdant earth. Three holes, about four inches in diameter, for the men inside to see and fire through, are neatly cut; one is in the front, and one on each side. Very frequently there is a fourth at the top., This is for the purpose of firing from at the wild-fowl as they pass over. The fowlers, lying upon their backs, discharge guess shots at the birds, who are only heard by the noise of their wings in their flight. Fowlers, with quick ears, attain considerable expertness in this guess-firing.

The numbers that are shot in this way are incredible. They are usually therefore sold at a cheap rate. At forty sous a couple, (1s. 8d. English) they are dear, but the price varies according to their condition.

In the larger drawing, I have given the appearance of the country and of the atmosphere at this season, and a duck-shooter with his gun near his hut, on the look out for coming flocks; but I fear wood engraving, excellent as it is for most purposes, will fall very short of the capability of engraving on copper to convey a correct idea of the romantic effect of the commingling cloud, mist, and sunshine, I have endeavoured to represent in this delightful part of France. Such as it is, it is at your service to do with as you please.

For myself, though for the sake of variety, I have now and then crept into a fowler's hut, and shot in ambuscade, I prefer open warfare, and I assure you I have had capital sport. That you may be acquainted with some of these wildfowl, I will just mention the birds I have shot here within the last three weeks, beginning with the godwit; their names in French are from my recollection of Buffon.

The Godwit.

Common Godwit, la grand barge.

Red Godwit, la barge rousse.

Cinereous Godwit, (Bewick).

Cambridge Godwit, (Latham).

Green-shanked Godwit, la barge variée.

Red-legged Godwit, le chevalier rouge.

Redshank, le chevalier aux pieds rouges.

Sandpipers.

Ruffs and Reeves, le combattant.

Green Sandpiper, le bécasseau, ou culblanc.

Common Sandpiper, la guignette.

Brown Sandpiper, (Bewick.)

Dunlin, la brunette.

Ox-eye, l'alouette de mer.

Little Stint, la petite alouette de mer, (Brisson) &c. &c.

Curlews.

Curlew, la courles.

Whimbiel, le petite courles.

Heron.

Common, le heron hupe.

Bittern, le butor.

Little Bittern, le blongois.

Ducks.

The common Wild Duck, le canard sauvage.

Gadwell, or Gray, le chipeau.

Pochard, penelope, le millovin.

Pintail, la canard à longue queue.

Golden-eye, le garrot.

Morillon, le morillon.

Tufted Duck, le petit morillon. (Brisson.)

Gargany, la sarcelle.

Teal, la petite sarcelle.

If you were here you should have a "gentleman's recreation," of the most delightful kind. Your propensity to look for "old masters," would turn into looking out for prime birds. The spotted red-shanks, or barkers, as they are sometimes called, would be fine fellows for you, who are fond of achieving difficulties. They come in small flocks, skimming about the different ponds into which they run to the height of the body, picking up insects from the bottom, and looking as if they had no legs. They are excessively wary, and above all, the most difficult to get near. Confound all "black letter" say I, if it keeps a man from such delightful scenes as I have enjoyed every hour since I came here; as to picture-loving—come and see these pictures which never tire by looking at. I like a good picture though myself, and shall pick up some prints at Paris to put with my others. You may be certain therefore of my collecting something for you, after the birds have left, especially wood cuts. I shall accomplish what I can in the scrap and story-book way, which is not quite in my line, yet I think I know what you mean. In my next you shall have something about lark-shooting, which, in England, is nothing compared with what the north of France affords.

I am, &c.

J. J. H.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

White Cedar. Cupressus thyoides.

Dedicated to St. Olympias.