July 26.

St. Anne, Mother of the Virgin. St. Germanus, Bp. A.D. 448.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Field Chamomile. Matricaria Chamomilla.

Dedicated to St. Anne.

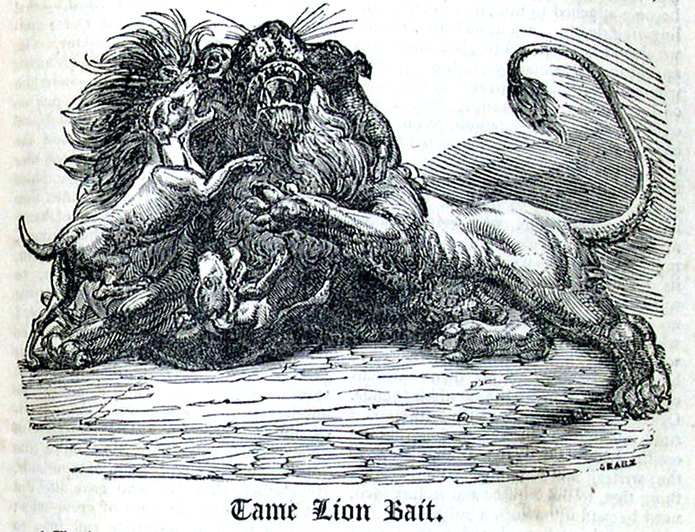

LION FIGHT.

On Tuesday, the 26th of July, 1825, there was a "fight," if so it might be called, between a lion and dogs, which is thus reported in the public journals:—

This extremely gratuitous, as well as disgusting, exhibition of brutality, took place, at a late hour on Tuesday evening, at Warwick; and, except that it was even still more offensive and cruel than was anticipated, the result was purely that which had been predicted in The Times newspaper.

The show was got up in an extensive enclosure, called the "Old Factory-yard," just in the suburbs of Warwick, on the road towards Northampton; and the cage in which the fight took place stood in the centre of a hollow square, formed on two sides by ranges of empty workshops, the windows of which were fitted up with planks on barrels as seats for the spectators; and, in the remaining two, by the whole of Mr. Wombwell's wild "collection," as they have been on show for some days past, arranged in their respective dens and travelling carriages.

In the course of the morning, the dogs were shown, for the fee of a shilling, at a public-house in Warwick, called the "Green Dragon." Eight had been brought over originally; but, by a mistake of locking them up together on the preceding night, they had fallen out among themselves, and one had been killed entirely; a second escaping only with the loss of an ear, and a portion of one cheek. The guardian of the beasts being rebuked for this accident, declared he could not have supposed they would have fought each other—being "all on the same side:" six, however, still remained in condition, as Mrs. Heidelberg expresses it, for the "runcounter."

The price of admission demanded in the first instance for the fight seemed to have been founded on very gross miscalculation. Three guineas were asked for seats at the windows in the first, second, and third floors of the unoccupied manufactory; two guineas for seats on the fourth floor of this building; one guinea for places at a still more distant point; and half-a guinea for standing room in the square. The appearance of the cage when erected was rather fragile, considering the furious struggle which was to take place within it. It measured fifteen feet square, and ten feet high, the floor of it standing about six feet from the ground. The top, as well as the sides, was composed merely of iron bars, apparently slight, and placed at such a distance from each other that the dogs might enter or escape between, but too close for the lion to follow. Some doubts were expressed about the sufficiency of this last precaution—merely because a number of "ladies," it was understood, would be present; but the ladies in general escaped that disgrace, for not a single female came; and, at all events, the attendant bear-wards swore in the most solemn way—that is to say, using a hundred imprecations instead of one—that the security of the whole was past a doubt. Towards afternoon the determination as to "prices" seemed a little to abate; and it was suspected that, in the end, the speculator would take whatever prices he could get. The fact became pretty clear, too, that no real match, nor any thing approaching to one, was pending; because the parties themselves, in their printed notices, did not settle any circumstances satisfactorily, under which the contest could be considered as concluded. Wheeler, Mr. Martin's agent, who had come down on Monday, applied to the local authorities to stop the exhibition; but the mayor, and afterwards, as we understood, a magistrate of the name of Wade, declined interfering, on the ground that, under Mr. Martin's present act, no steps could be taken before the act constituting "cruelty" had been committed. A gentleman, a quaker, who resides near Warwick, also went down to the menagerie, in person, to remonstrate with Mr. Wombwell; but, against the hope of letting seats at "three guineas" a-head, of course his mediation could have very little chance of success.

In the mean time, the unfortunate lion lay in a caravan by himself all day, in front of the cage in which he was to be baited, surveying the preparations for his own annoyance with great simplicity and apparent good humour; and not at all discomfited by the notice of the numerous persons who came to look at him. In the course of the day, the dogs who were to fight were brought into the menagerie in slips, it being not the least singular feature of this combat that it was to take place immediately under the eyes of an immense host of wild beasts of all descriptions (not including the human spectators); three other lions; a she wolf, with cubs; a hyæna; a white bear; a lioness; two female leopards, with cubs; two zebras, male and female; a large assortment of monkeys; and two wild asses; with a variety of other interesting foreigners, being arranged within a few yards of the grand stand.

These animals, generally, looked clean and in good condition; and were (as is the custom with such creatures when confined) perpetually in motion; but the dogs disappointed expectation—they were very little excited by the introduction. They were strong, however, and lively; crossed, apparantly the majority of them, between the bull and the mastiff breed; one or two showed a touch of the lurcher, a point in the descent of fighting dogs which is held to give an increased capacity of mouth. The average weight of those which fought was from about five and thirty to five and forty pounds each; one had been brought over that weighed more than sixty, but he was on some account or other excluded from the contest.

The cub leopards were "fine darling little creatures," as an old lady observed in the morning, fully marked and coloured, and about the size of a two months' old kitten. The young wolves had a haggard, cur-like look; but were so completely like sheep-dog puppies, that a mother of that race might have suckled them for her own. A story was told of the lion "Nero" having already had a trial in the way of "give and take," with a bull bitch, who had attacked him, but, at the first onset, been bitten through the throat. The bitch was said to have been got off by throwing meat to the lion; and if the account were true, the result was only such as with a single dog, against such odds, might reasonably have been expected. Up to a late hour of the day, the arrival of strangers was far less considerable than had been anticipated; and doubts were entertained, whether, in the end, the owner of the lion would not declare off.

At a quarter past seven, however, in the evening, from about four to five hundred persons of different descriptions being assembled, preparations were made for commencing[.]

The Combat.

The dens which contained the animals on show were covered in with shutters; the lion's travelling caravan was drawn close to the fighting cage, so that a door could be opened from one into the other; and the keeper, Wombwell, then going into the travelling caravan, in which another man had already been staying with the lion for some time, the animal followed him into the cage as tamely as a Newfoundland dog. The whole demeanour of the beast, indeed, was so quiet and generous, that, at his first appearance, it became very much doubted whether he would attempt to fight at all. While the multitude shouted, and the dogs were yelling in the ground below, he walked up and down his cage, Wombwell still remaining in it, with the most perfect composure, not at all angered, or even excited; but looking with apparently great curiostiy at his new dwelling and the objects generally about him; and there can hardly be a question, that, during the whole contest, such as it turned out, any one of the keepers might have remained close to him with entire safety.

Wombwell, however, having quitted the cage, the first relay of dogs was laid on. These were a fallow-coloured dog, a brown with white legs, and a third brown altogether—averaging about forty pounds in weight a-piece, and described in the printed papers which were distributed, by the names of Captain, Tiger, and Turk. As the dogs were held for a minute in slips, upon the inclined plane which ran from the ground to the stage, the lion crouched on his belly to receive them; but with so perfect an absence of anything like ferocity, that many persons were of opinion he was rather disposed to play: at all events, the next moment showed clearly that the idea of fighting, or doing mischief to any living creature, never had occurred to him.

At the first rush of the dogs—which the lion evidently had not expected, and did not at all know how to meet—they all fixed themselves upon him, but caught only by the dewlap and the mane. With a single effort, he shook them off, without attempting to return the attack. He then flew from side to side of the cage, endeavouring to get away; but in the next moment the assailants were upon him again, and the brown dog, Turk, seized him by the nose, while the two others fastened at the same time on the fleshy part of his lips and underjaw. The lion then roared dreadfully, but evidently only from the pain he suffered—not at all from anger. As the dogs hung to his throat and head, he pawed them off by sheer strength; and in doing this, and in rolling upon them, did them considerable mischief; but it amounts to a most curious fact, that he never once bit, or attempted to bite, during the whole contest, or seemed to have any desire to retaliate any of the punishment which was inflicted upon him. When he was first "pinned," for instance, (to use the phraseology of the bear-garden,) the dogs hung to him for more than a minute, and were drawn, holding to his nose and lips, several times round the ring. After a short time, roaring tremendously, he tore them off with his claws, mauling two a good deal in the operation, but still not attempting afterwards to act on the offensive. After about five minutes' fighting, the fallow-coloured dog was taken away, lame, and apparently much distressed, and the remaining two continued the combat alone, the lion still working only with his paws, as though seeking to rid himself of a torture, the nature of which he did not well understand. In two or three minutes more, the second dog, Tiger, being dreadfully maimed, crawled out of the gcae [cage]; and the brown dog, Turk, which was the lightest of the three, but of admirable courage, went on fighting by himself. A most extraordinary scene then ensued: the dog, left entirely alone with an animal of twenty times its weight, continued the battle with unabated fury, and, though bleeding all over from the effect of the lion's claws, seized and pinned him by the nose at least half a dozen times; when at length, releasing himself with a desperate effort, the lion flung his whole weight upon the dog, and held him lying between his fore paws for more than a minute, during which he could have bitten his head off a hundred times over, but did not make the slightest effort to hurt him. Poor Turk was then taken away by the dog-keepers, greivously mangled but still alive, and seized the lion, for at least the twentieth time, the very same moment that he was released from under him.

It would be tiresome to go at length into the detail of the "second fight," as it was called, which followed this; the undertaking being to the assembly—for the notion of "match" now began to be too obvious a humbug to be talked about—that there should be two onsets, at twenty minutes' interval, by three dogs at each time. When the last dog of the first set, Turk, was removed, poor Nero's temper was just as good as before the affair began. The keeper, Wombwell, went into the cage instantly, and alone, carrying a pan of water, with which he first sluiced the animal, and then offered him some to drink. After a few minutes the lion laid down, rubbing the parts of his head which had been torn (as a cat would do) with his paw; and presently a pan of fresh water being brought, he lapped out of it for some moments, while a second keeper patted and caressed him through the iron grate. The second combat presented only a repetition of the barbarities committed in the first, except that it completely settled the doubt—if any existed—as to a sum of money being depending. In throwing water upon the lion, a good deal had been thrown upon the stage. This made the floor of course extremely slippery; and so far it was a very absurd blunder to commit. But the second set of dogs let in being heavier than the first, and the lion more exhausted, he was unable to keep his footing on the wet boards, and fell in endeavouring to shake them off, bleeding freely from the nose and head, and evidently in a fair way to be seriously injured. The dogs, all three, seized him on going in, and he endeavoured to get rid of them in the same way as before, using his paws, and not thinking of fighting, but not with the same success. He fell now, and showed symptoms of weakness, upon which the dogs were taken away. This termination, however, did not please the crowd, who cried out loudly that the dogs were not beaten. Some confusion then followed; after which the dogs were again put in, and again seized the lion, who by this time as well as bleeding freely from the head, appeared to have got a hurt in one of his fore feet. At length the danger of mischief becoming pressing, and the two divisions of the second combat having lasted about five minutes, Mr. Wombwell announced that he gave up on the part of the lion; and the exhibition was declared to be at an end.

The first struggle between the lion and his assailants lasted about eleven minutes, and the last something less than five; but the affair altogether wanted even the savage interest which generally belongs to a common bull or bear bait. For, from the beginning of the matter to the end, the lion was merely a sufferer—he never struck a blow. The only picturesque point which could present itself in such a contest would have been, the seeing an animal like the lion in a high state of fury and excitation; but before the battle began, we felt assured that no such event would take place; because the animal in question, had not merely been bred up in such a manner as would go far to extinguish all natural disposition to ferocity, but the greatest pains had been taken to render him tame, and gentle, and submissive. Wombwell, the keeper, walked about in the cage with the lion at least as much at his ease as he could have done with any one of the dogs who were to be matched against him. At the end of the first combat, the very moment the dogs were removed, he goes into the cage and gives him water. At the end of the last battle, while he is wounded and bleeding, he goes to him again without the least hesitation. Wombwell must have known, to

Tame Lion Bait.

"The dogs would not give him a moment's respite, and all three set on him again, while the poor animal howling with pain, threw his great paws awkwardly upon them as they came." — Morning Herald.

certainty, that the animal's temper was not capable of being roused into ferocity. It might admit, perhaps, of some question, whether the supposed untameable nature of many wild animals is not something overrated: and whether it would not be the irresistible strength of a domestic lion (in case he should become excited,) that could render him a dangerous inmate, rather than any probability that he would easily become furious; but, as regards the particular animal in question, and the battle which he had to fight, he evidently had no understanding of it, no notion that the dog was his enemy. A very large dog, the property of a gentleman in Warwick, was led up to his caravan on the day before the fight; this dog's appearance did not produce the slightest impression upon him. So, with the other wild beasts of Wombwell's collection, who were shown to the fighting dogs, as we observed above, on the morning of Tuesday, not one of them appeared to be roused by the meeting in the smallest degree. A common house cat would have been upon the qui vive, and aux mains too probably, in a moment. All the contest that did take place arose out of the fact, that the dogs were of a breed too small and light to destroy an animal of the lion's weight and strength, even if he did not defend himself. It was quite clear, from the moment when the combat began, that he had no more thought or knowledge of fighting, than a sheep would have had under the same circumstances. His absolute refusal to bite is a curious fact; he had evidently no idea of using his mouth or teeth as a means for his defence. The dogs, most of them, showed considerable game; the brown dog Turk, perhaps as much as ever was exhibited, and none of them seemed to feel any of that instinctive dread or horror which some writers have attributed to dogs in the presence of a lion.

It would be a joke to say any thing about the feelings of any man, who, for the sake of pecuniary advantage, could make up his mind to expose a noble animal which he had bred, and which had become attached to him, to a horrible and lingering death. About as little reliance we should be disposed to place upon any appeal to the humanity of those persons who make animal suffering—in the shape of dog-fighting, bear-baiting, &c., a sort of daily sport—an indemnification, perhaps, for the not being permitted to torture their fellow-creatures. But as, probably, a number of persons were present at this detesable exhibition, which we have been describing, who were attracted merely by its novelty, and would be as much disgusted as we ourselves were with its details, we recommend their attention to the following letter, which a gentleman, a member of the Society of Friends, who applied personally to Mr. Wombwell to omit the performance, delivered to him as expressive of his own opinions upon the question, and those of his friends. Of course, addressed to such a quarter, it produced no effect; but it does infinite credit both to the head and heart of the writer, and contains almost every thing that, to honourable and feeling men, need be said upon such a subject::—

"Friend,—I have heard with a great degree of horror, of an intended fight between a lion that has long been exhibited by thee, consequently has long been under thy protection, and six bull-dogs. I seem impelled to write to thee on the subject, and to entreat thee, I believe in christian love, that, whatever may be thy hope of gain by this very cruel and very disgraceful exhibition, thou wilt not proceed. Recollect that they are God's creatures, and we are informed by the holy scriptures, that not even a sparrow falls to the ground without his notice; and as this very shocking scene must be to gratify a spirit of cruelty, as well as a spirit of gambling,—for it is asserted that large sums of money are wagered on the event of the contest,—it must be marked with divine displeasure. Depend upon it that the Almighty will avenge the sufferings of his tormented creatures on their tormentors; for, though he is a God of love, he is also a God of justice; and I believe that no deed of cruelty has ever passed unpunished. Allow me to ask thee how thou wilt endure to see the noble animal thou hast so long protected, and which has been in part the means of supplying thee with the means of life, mangled and bleeding before thee? It is unmanly, it is mean and cowardly, to torment any thing that cannot defend itself,—that cannot speak to tell its pains and sufferings,—that cannot ask for mercy. Oh, spare thy poor lion the pangs of such a death as may perhaps be his,—save him from being torn to pieces—have pity on the dogs that may be torn by him. Spare the horrid spectacle—spare thyself the sufferings that I fear will yet reach thee if thou persist—show a noble example of humanity. Whoever have persuaded thee to expose thy lion to the chance of being torn to pieces, or of tearing other animals, are far beneath the brutes they torment, are unworthy the name of men, or rational creatures. Whatever thou mayest gain by this disgraceful exhibition will, I fear, prove like a canker-worm among the rest of thy substance. The writer of this most earnestly entreats thee to refrain from the intended evil, and to protect the animals in thy possession from all unnecessary suffering. The practice of benevolence will afford thee more true comfort than the possession of thousands. Remember, that He who gave life did not give it to be the sport of cruel man; and the He will assuredly call man to account for his conduct towards his dumb creatures. Remember, also, that cowards are always cruel, but the brave love mercy, and delight to save. With sincere desire for the preservation of thy honour, as a man of humanity, and for thy happiness and welfare, I am, thy friend,

"S. HOARE."

Mr. Hoare's excellent letter, with the particulars of this brutal transaction, thus far, are from The Times newspaper which observes in its leading article thus:

"With great sincerity we offered a few days ago our earnest remonstrance against the barbarous spectacle then preparing, and since, in spite of every better feeling, indulged—we mean the torture of a noble lion, with the full consent, and for the profit, of a mercenary being, who had gained large sums of money by hawking the poor animal about the world and exhibiting him. It is vain, however, to make any appeal to humanity where none exists, or to expatiate on mercy, justice, and retribution hereafter, when those whom we strive to influence have never learned that language in which alone we can address them.

"Little more can be said upon this painful and degrading subject, beyond a relation of the occurrence itself, which it was more our wish than our hope to have prevented. Nothing, at least, could be so well said by any other person, as it has by a humane and eloquent member of the Society of Friends, in his excellent though unavailing letter to Wombwell. What must have been the texture of that mind, on which such sentiments could make no impression?"

The question may be illustrated by Wombwell's subsequent conduct.

To the preceding account, extracted from The Times, additional circumstances are subjoined, in order to preserve a full record of this disgraceful act.

The Morning Herald says—For several months the country has been amused with notices that a fight between a lion and dogs was intended, and time and place were for than once appointed. This had the desired effect—making the lion an object of great attraction in the provincial towns, and a golden harvest was secured by showing him at two shillings a head. The next move was to get up such a fight as would draw all the world from London, as well as from the villages, to fill places marked at one and two guineas each to see it; and lastly, to find dogs of such weight and inferior quality as to stand no chance before an enraged lion—thus securing the lion from injury, and making him still a greater lion than before, or that the world ever saw to be exhibited as the wonderful animal that beat six British bred mastiffs. The repeated disappointments as to time and place led people to conclude that the affair was altogether a hoax, and the magnitude of the stake of 5,000l. said to be at issue, was so far out of any reasonable calculation, that the whole was looked upon as a fabrication, and the majority became incredulous on the subject. Nay, the very persons who saw the lion and the dogs, and the stage, disbelieved even to the last moment that the fight was in reality intended. But the proprietor of the concern was too good a judge to let the flats altogether escape him, though his draught was diminished from having troubled the waters too much. Wombwell, the proprietor, as the leader of a collection of wild beasts, may be excused for his proficiency in trickery, which is the essence and spirit of his calling, but we think him accountable, as a man, for his excessive cruelty in exposing a poor animal that he has reared himself, and made so attached that it plays with him, and fondles him like a spaniel—that has never been taught to know its own powers, or the force of its savage nature, to the attacks of dogs trained to blood, and bred for fighting. The lion now five years old, was whelped in Edinburgh, and has been brought up with so much softness, that it appears as inoffensive as a kitten, and suffers the attendants of the menagerie to ride upon its back or to sleep in its cage. Its nature seems to be gentleness itself, and its education has rendered it perfectly domestic, and deprived it of all savage instinct. In the only experiment made upon its disposition, he turned from a dog which had been run at him, and on which he had fastened, to a piece of meat which was thrown into the cage. Nero is said to be one of the largest lions ever exhibited, and certainly a finer or more noble looking animal cannot be imagined.

Wombwell announced in his posting-bills at Birmingham, Coventry, Manchester, and all the neighbouring towns, that the battle was to be for 5,000l., but communicated, by way of secret, that, in reality, it was but 300l. a side, which he asserted was made good with the owner of the dogs on Monday night, at the Bear, in Warwick; but who the owner of the dogs was, or the maker of the match, it was impossible to ascertain; and though well aware of the impropriety of doubting the authority of the keeper of the menagerie, we must admit that our impression is, that no match was made, that no wagers were laid, and that the affair was got up for the laudable purpose hinted at in the commencement of this notice. The dogs to be sure, were open to the inspection of the curious on Monday, and a rough-coated, game-keeping, butcher-like, honest, ruffianly person from the north, announced himself as ther ostensible friend on the occasion; but by whom employed he was unwilling to declare. His orders were to bring the dogs to "the scratch," and very busy we saw him preparing them for slaughter, and anointing the wounds of one little bitter animal that got its head laid open in the course of the night, while laudably engaged in mangling the throat and forcing out the windpipe of one of its companions, near whom it had been unfortunately chained. The other dogs were good-looking savage vermin, averaging about 40lbs. weight; one of them being less than 30lbs., and the largest not over 60lbs. Four were described as real bull dogs, and the other bull and mastiff crossed. The keeper said they were quite equal to the work; but, to one not given to the fancy dog line, they appeared quite unequal to attack and master a lion, many times as large as all the curs put together. Wedgbury, a person well known in London for his breed of dogs, brought down one over 70lbs., of most ferocious and villanous aspect, with the intention of entering him for a run, but it was set aside by Wombwell; thus affording another proof that Wombwell had the whole concern in his hands, and selected dogs unable, from their weight or size, to do a mortal injury to his lion.

Wombwell appointed seven in the evening as the hour of combat. Accommodations were prepared for about a thousand people, but owing to the frequent disappointments and to the exorbitant prices demanded, not more than two hundred and fifty persons appeared willing or able to pay for the best places, and about as many more admitted on the ground. The charge to the former was reduced to two guineas and one guinea, and to the latter from half a guinea to 7s. 6d. About 400l. was collected, from which, deducting 100l. for expenses, 300l. was cleared by the exhibition, a sum barely the value of the lion if he should lose his life in the contest. The cages in which the other beasts were confined, were all closed up. It was well understood that no match had really been made, and consequently no betting of consequence took place, but among a few countrymen, who, contrasting the size of the lion with the dogs, backed him at 2 to 1.

Wombwell, having no longer the fear of the law before him, proceeded to complete his engagements, and distributed the following bills:—

"THE LION FIGHT.

"The following are the conditions under which the combat between Nero and the dogs will be decided:—

"1st. Three dogs are at once to be slipped at him.

"2d. If one or any of them turn tail, he or they are to be considered as beaten, and no one of the other remaining three shall be allowed to attack him until twenty minutes shall be expired, in order to give Nero rest; for he must be allowed to beat the first three, one by one, or as he may choose before the remaining three shall be started.

"After the expiration of the stipulated time, the remaining three dogs are to start according to the foregoing rules, and be regulated as the umpires shall adjudge.

"The dogs to be handled by Mr. Edwards, John Jones, and William Davis, assisted by Samuel Wedgbury.

"1. Turk, a brown coloured dog.—2. Captain, a fallow and white dog, with skewbald face.—[3.] Tiger, a brown dog, with white legs.—4. Nettle, a little brindled bitch, with black head.—5. Rose, a skewbald bitch.—6. Nelson, a white dog, with brindled spots."

The place chosen for the exhibition was, as we have siad, the yard of a large factory, in the centre of which an iron cage, about fifteen feet square, elevated five feet from the ground, was fixed as the place of combat. This was secured at top by strong open iron work, and at the sides by wrought iron bars, with spaces sufficient between to admit the dogs, and an ascending platform for them to run up. Temporary stations were fixed at the windows of the factory, and all round the yard, and the price for these accomodations named at the outrageous charge of three guineas for the best places, two guineas for the second, one for the third, and half a guinea for standing on the ground. Though the place was tolerably well fitted up, it fell far short of what the mind conceived should be the arena for for [sic] such a combat; but Mr. Wombwell cared not a jot for the pleasures of the imagination, and counted only the golden sovereign to which every deal board would be turned in the course of the day, while his whole collection of wild beasts, lions, tigresses, and wolves, with their whelps and cubs, apes and monkeys, made up a goodly show, and roared and grinned in concert, delighted with the bustle about them, as if in anticipation of the coming fun.

The Morning Chronicle says,---The place chosen for the combat, was the factory yard in which the first stage was erected for the fight between Ward and Cannon. This spot, which was, in fact, extremely well calculated for the exhibition, was now completely enclosed. We formerly stated that two sides of the yard were formed by high buildings, the windows of which looked upon the area; the vacant spaces were now filled up by Mr. Wombwell's collection of wild beasts, which were openly exposed, in their respective cages, on the one side, and by paintings and canvass on the other, so that, in fact, a compact square was formed, which was securely hidden from external observation. There was but one door of admission, and that was next the town. Upon the tops of the cages seats were erected, in amphitheatrical order; and for accommodation here, one guinea was charged. The higher prices were taken for the windows in the factories, and the standing places were 10s. each. The centre of the square was occupied by the den, a large iron cage, the bars of which were usfficiently far asunder to permit the dogs to pass in and out, while the caravan in which Nero was usually confined, was drawn up close to it. The den itself was elevated upon a platform, fixed on wheels about four feet from the ground, and an inclined plane formed of thick planks was placed against it, so as to enable the dogs to rush to the attack. It was into this den that Nero was enticed to be baited. Wombwell's trumpeters then went forth, mounted on horses, and in gaudy array, to announce the fight, which was fixed to take place between five and seven in the evening. They travelled to Leamington, and the adjacent villages; but to have done good they should have gone still farther, for all who ventured from a distance on speculation, announced that those they left behind fully believed that their labour would be in vain.

The dogs attracted a good deal of curiosity. They took up their quarters at the Green Dragon, where they held a levee, and a great number of persons paid sixpence each to have an opportunity of judging of their qualities, and certainly as far as appearance went, they seemed capable of doing much mischief.

On Tuesday morning several persons were admitted to the factory to see the preparations, and at about ten o'clock the dogs were brought in, They seemed perfectly ready to quarrel with each other, but did not evince any very hostile disposition either towards Nero, who, from his private apartment, eyed them with great complacency, or towards the other lion and lionesses by whom they were surrounded, and who, as it were, taunted them by repeated howlings, in which Nero joined chorus with his deep and sonorous voice. The cruelty of unnecessarily exposing such an animal to torture, naturally produced severe comments; and among other persons, a quaker, being in the town of Warwick, waited upon Mr. Wombwell, on Tuesday morning, with Mr. Hoare's letter, which he said he had received twenty miles from the town. However well meant this letter was, and that it arose in the purest notives of christian charity no man could doubt: with Mr. Wombwell it had no effect. He looked at his preparations, he looked at his lion, and he cast a glance forward to his profits, and then shook his head.

The pain of the lion was to be Wombwell's profit; and between agony to the animal, and lucre to himself, the showman did not hesitate.

From the Morning Herald report of this lion bait, several marked circumstances are selected, and subjoined under a denomination suitable to their character—viz:—

POINTS OF CRUELTY.

First Combat.

1. The dogs, as if in concert, flew at the lion's nose and endeavoured to pin him, but Nero still kept up his head, striking with his fore-paws, and seemingly endeavouring more to get rid of the annoyance than to injure them.

2. They unceasingly kept goading, biting, and darting at his nose, sometimes hanging from his mouth, or one endeavouring to pin a paw, while the others mangled the head.

3. Turk, made a most desperate spring at the nose, and absolutely held there for a moment, while Captain and Tiger each seized a paw; the force of all three brought the lion from his feet, and he was pinned to the floor for the instant.

4. His great strength enabled him to shake off the dogs, and then, as if quite terrified at their fury, he turned round and endeavoured to fly; and if the bars of the cage had not confined him, would certainly have made away. Beaten to the end of the cage, he lay extended in one corner, his great tail hanging out through the bars.

5. Nero appeared quite exhausted, and turned a forlorn and despairing look on every side for assistance. The dogs became faint, and panting with their tongues out, stood beside him for a few seconds, until cheered and excited by their keepers' voices they again commenced the attack, and roused Nero to exertion. The poor beast's heart seemed to fail him altogether at this fresh assault, and he lay against the side of the stage totally defenceless, while his foes endeavoured to make an impression on his carcase.

6. Turk turned to the head once more, and goaded the lion, almost to madness, by the severity of his punishment on the jaws and nose.

7. The attack had continued about six minutes, and both lion and dogs were brought to a stand still; but Turk got his wind in a moment, and flew at his old mark of the jaw, which he laid hold of, and hung from it, while Nero roared with anguish.

8. The lion attempted to break away, and flung himself with desperation against the bars of the stage—the dogs giving chase, darting at his flank, and worrying his head, until all three being almost spent, another pause took place, and the dogs spared their victim for an instant.

9. Turk got under his chest, and endeavoured to fix himself on his throat, while Tiger imitating his fierceness, flew at the head. This joint attack worked the spirit of the poor lion a little, he struck Tiger from him with a severe blow of his paw, and fell upon Turk with all the weight of the fore part of his body, and then grasping his paws upon him, held him as in a vice.

10. Here the innocent nature of poor Nero was conspicuous, and the brutality of the person who fought him made more evident, for the fine animal having its totally defenceless enemy within the power of his paw, did not put it upon him and crush his head to mince meat, but lay with his mouth open, panting for breath, nor could all the exertions of Wombwell from outside the bars direct his fury at the dog who was between his feet.

11. It now became a question what was to be done, as Tiger crawled away and was taken to his kennel, and there appeared no chance of the lion moving from his position and relieving the other dog. However, after about a minute's pause, the lion opened his hold, released the dog and got upon his legs, as if he became at ease when freed from the punishment of his assailants.

12. Turk finding himself at liberty, faced the lion, flew at his nose, and there fastened himself like a leech, while poor Nero roared again with anguish. The lion contrived, by a violent exertion, to shake him off. Thus terminated the first round in eleven minutes.

Second Combat.

1. The three dogs were brought to their station, and pointed and excited at the lion; but the inoffensive, innocent creature walked about the stage, evidently unprepared for a second attack.

2. Word being given, the three dogs were slipped at once, and all darted at the flank of the lion, amid the horrid din of the cries of their handlers, and the clapping and applause of the mob. The lion finding himself again assailed, did not turn against his foes, but broke away with a roar, and went several times round the cage seeking to escape from their fury.

3. The dogs pursued him, and all heading him as if by the same impulse, flew at his nose together, brought him down, and pinned him to the floor. Their united strength being now evidently superior to his, he was held fast for several seconds, while the mob shouted with renewed delight.

4. Nero, by a desperate exertion, cleared himself at length from their fury, and broke away; but the dogs agains gave chase and headed him once more, sprung at his nose, and pinned him all three together. The poor beast, lacerated and torn, groaned with pain and heart-rending anguish, and a few people, with something of a human feeling about them, called out to Wombwell to give in for the lion; but he was callous to their entreaties, and Nero was left to his fate.

5. Poor Nero lay panting on the stage, his mouth, nose, and chaps full of blood, while a contest took place between Wombwell and the keepers of the dogs, the one refusing, and the other claiming the victory. At length brutality prevailed, and the dogs were slipped again for the purpose of finishing.

6. Nero was unable to rise and meet them, and suffered himself to be torn and pulled about as they pleased; while the dogs, exulting over their prey, mumbled his carcase, as he lay quite powerless and exhausted. Wombwell then seeing that all chance of the lion coming round was hopeless, and dreading that the death of the poor animal must be the consequence of further punishment, gave in at last, and the handlers of the dogs laid hold of them by the legs, and pulled them by main force away, on which another shout of brutal exultation was set up, and the savage sport of the day concluded.

Nero's Tameness.

Had he exerted a tithe of his strength, struck with his paws, or used his fangs, he must have killed all the dogs, but the poor beast never bit his foes, or attempted any thing further than defending himself from an annoyance. On the whole, the exhibition was the most brutal we have ever witnessed, and appears to be indefensible in every point of view.

In reprobating the baiting of this tame lion by trained and savage dogs, the periodical press has been unanimous. The New Times says, "we rejoice to observe the strong feeling of aversion with which the public in general have heard of this cruel exhibition. As a question of natural history, it may be deemed curious to ascertain the comparative ferocity of the lion and the bull-dog; but even in this respect the Warwick fight cannot be deemed satisfactory; for though the lion was a large and majestic animal, yet, as he had been born and brought up in a domestic state, he had evidentlylittle [sic] or nothing of the fury which a wild animal of the same species evinces in combat. Burron observes, that 'the lion is very susceptible of the impressions given to him, and has always docility enough to be rendered tame to a certain degree.' He adds, that 'the lion, if taken young, and brought up among domestic animals, easily accustoms himself to live with them, and even to play without doing them injury; that he is mild to his keeper, and even caressing, especially in the early part of his life; and that if his natural fierceness now and then breaks out, it is seldom turned against those who have treated him with kindness.' These remarks of the great naturalist are very fully confirmed by the conduct of poor Nero; for both before and after the combat, he suffered his keeper, Wombwell, with impunity to enter his den, give him water to drink, and throw the remainder over his head. — We begin now to feel that a man has no right to torment inferior animals for his amusement; but it must be confessed that this sentiment is rather of recent predominance. The gladiatorial shows of Rome, the quail-fights of India, the bull-fights of Spain, may, in some measure, keep our barbarous ancestors in countenance; but the fact is, that bear-baiting, badger-baiting, bull-baiting, cock-fighting, and such elegant modes of setting on poor animals to worry and torment each other, were, little more than a century ago, the fashionable amusement of persons in all ranks of life. They have gradually descended to the lowest of the vulgar; and though there always will be found persons who adopt the follies and vices of their inferiors, yet these form a very small and inconsiderable minority of the respectable classes; and in another generation it will probably be deemed disgraceful in a gentleman to associate, on any occasion, with prize-fighters and pickpockets." By right education, and the diffusion of humane principles, we may teach youth to shun the inhuman example of their forefathers.

WOMBWELL'S SECOND LION BAIT.

Determined not to forego a shilling which could be obtained by the exposure of an animal to torture, Wombwell in the same week submitted another of his lions to be baited.

The Times, in giving an account of this renewed brutality, after a forcible expression of its "disgust and indignation at the cruelty of the spectacle, and the supineness of the magistracy," proceeds thus: "Wombwell has, notwithstanding the public indignation which accompanied the exposure of the lion Nero to the six dogs, kept his word with the lovers of cruel sports by a second exhibition. He matched his 'Wallace,' a fine lion, cubbed in Scotland, against six of the best dogs that could be found. Wallace's temper is the very opposite of that of the gentle Nero. It is but seldom that he lets even his feeders approach him, and he soon shows that he cannot reconcile himself to familiarity from any creature not of his own species. Towards eight o'clock the factory-yard was well attended, at 5s. each person, and soon after the battle commenced. The lion was turned from his den to the same stage on which Nero fought. The match was—1st. Three couples of dogs to be slipped at him, two at a time—2d. Twenty minutes or more, as the umpires should think fit, to be allowed between each attack—3d. The dogs to be handed to the cage once only. Tinker, Ball, Billy, Sweep, Turpin, Tiger."

THE FIGHT.

"In the first round, Tinker and Ball were let loose, and both made a gallant attack; the lion having waited for them as if aware of the approach of his foes. He showed himself a forest lion, and fought like one. He clapped his paw upon poor Ball, took Tinker in his teeth, and deliberately walked round the stage with him as a cat would with a mouse. Ball, released from the paw, worked all he could, but Wallace treated his slight punishment by a kick now and then. He at length dropped Tinker, and that poor animal crawled off the stage as well as he could. The lion then seized Ball by the mouth, and played precisely the same game with him as if he had actually been trained to it. Ball would have been almost devoured, but his second got hold of him through the bars, and hauled him away. Turpin, a London, and Sweep, a Liverpool dog, made an excellent attack, but it was three or four minutes before the ingenuity of their seconds could get them on. Wallace squatted on his haunches, and placed himself erect at the slope where the dogs mounted the stage, as if he thought they dared not approach. The dogs, when on, fought gallantly; but both were vanquished in less than a minute after their attack. The London dog bolted as soon as he could extricate himself from the lion's grasp, but Sweep would have been killed on the spot, but he was released. Wedgbury untied Billy and Tiger, casting a most piteous look upon the wounded dogs around him. Both went to work. Wallace seized Billy by the loins, and when shaking him, Tiger having run away, Wedgbury cried out, 'There, you see how you've gammoned me to have the best dog in England killed.' Billy, however, escaped with his life; he was dragged through the railing, after having received a mark in the loins, which (if he recovers at all) will probably render him unfit for any future contest[.] The victory of course was declared in favour of the lion.—Several well-dressed women viewed the contest from the uppr apartment of the factory."—Women!

Lion Fights in England.

It is more than two hundred years since an attempt has been made in this country to fight a lion against dogs. In the time of James I., the exhibition took place for the amusement of the court. Those who are curious on the subject, will find in "Seymour's Survey," a description of an experiment of that nature, in 1610. Two lions and a bear were first put into a pit together, but they agreed perfectly well, and disappointed the royal spectators in not assaulting each other. A high-spirited horse was then put in with them, but neither the bear nor the lions attacked him. Six mastiffs were next let loose, but they directed all their fury against the horse, flew upon it, and would have torn it in pieces, but for the interference of the bear-wards, who went into the pit, and drew the dogs away, the lions and bear remaining unconcerned. Your profound antiquarian will vouch for the truth of this narration, but it goes a very little way to establish the fact of an actual fight between a lion and dogs. Perhaps an extract from Stow's Annals may be more satisfactory. It is an account of a contest stated to have taken place in the presence of James I., and his son, prince Henry. "One of the dogs being put into the den, was soon disabled by the lion, who took him by the head and neck, and dragged him about. Another dog was then let loose, and served in the same manner; but the third being put in, immediately seized the lion by the lip, and held him for a considerable time; till being severely torn by his claws, the dog was obliged to quit his hold; and the lion, greatly exhausted by the conflict, refused to renew the engagement; but, taking a sudden leap over the dogs, fled into the interior of his den. Two of the dogs soon died of their wounds; the third survived, and was taken great care of by the prince, who said, 'he that had fought with the king of beasts should never after fight with an inferior creature.'"*[1]

Lion fight at Vienna.

There was a lion fight at the amphitheatre of Vienna, in the summer of 1790, which was almost the last permitted in that capital.

The amphitheatre at Vienna embraced an area of from eighty to a hundred feet in diameter. The lower part of the structure comprised the dens of the different animals. Above those dens, and about ten feet from the ground, were the first and principal seats, over which were galleries. In the course of the entertainment, a den was opened, out of which stalked, in free and ample range, a most majestic lion; and, soon after, a fallow deer was let into the circus from another den. The deer instantly fled, and bounded round the circular space, pursued by the lion; but the quick and sudden turnings of the former continually baulked the effort of its pursuer. After this ineffectual chase had continued for several minutes, a door was opened, through which the deer escaped; and presently five or six of the large and fierce Hungarian mastiffs were sent in. The lion, at the moment of their entrance, was leisurely returning to his den, the door of which stood open. The dogs, which entered behind him, flew towards him in a body, with the utmost fury, making the amphitheatre ring with their barkings. When they reached the lion, the noble animal stopped, and deliberately turned towards them. The dogs instantly retreated a few steps, increasing their vociferations, and the lion slowly resumed his progress towards his den. The dogs again approached; the lion turned his head; his adversaries halted; and this continued until, on his nearing his den, the dogs separated, and approached him on different sides. The lion then turned quickly round, like one whose dignified patience could brook the harrassment of insolence no longer. The dogs fled far, as if instinctively sensible of the power of wrath they had at length provoked. One unfortunate dog, however, which had approached too near to effect his escape, was suddenly seized by the paw of the lion; and the piercing yells which he sent forth quickly caused his comrades to recede to the door of entrance at the opposite site of the area, where the stood in a row, barking and yelling in concert with their miserable associate.

After arresting the struggling and yelling prisoner for a short time, the lion couched upon him with his forepaws and mouth. The struggles of the sufferer grew feebler and feebler, until at length he became perfectly motionless. We all concluded him to be dead. In this composed posture of executive justice, the lion remained for at least ten minutes, when he majestically rose, and with a slow step entered his den, and disappeared. The apparent corpse continued to lie motionless for a few minutes; presently the dog, to his amazement, and that of the whole amphitheatre, found himself alive, and rose with his nose pointed to the ground, his tail between his hind legs pressing his belly, and, as soon as he was certified of his existence, he made off for the door in a long trot, through which he escped with his more fortunate companions.*[2]

Another Lion Fight at Vienna.

Of late years the truth of the accounts which have been so long current, respecting the generous disposition of the lion, have been called in question. Several travellers, in their accounts of Asia and Africa, describe him as of a more rapacious and sanguinary disposition than had formerly been supposed, although few of them have had the opportunity to make him a particular object of their attention.

A circumstance that occurred not long since in Vienna seems, however, to confirm the more ancient accounts. In the year 1791, at which period the custom of baiting wild beasts still existed in that city, a combat was to be exhibited between a lion and a number of large dogs. As soon as the noble animal made his appearance, four large bull-dogs were turned loose upon him, three of which, however, as soon as they came near him, took fright, and ran away. One only had courage to remain, and make the attack. The lion, however, without rising from the ground upon which he was lying, showed him, by a single stroke with his paw, how greatly his superior he was in strength; for the dog was instantly stretched motionless on the ground. The lion drew him towards him, and laid his fore-paws upon him in such a manner that only a small part of his body could be seen. Every one imagined that the dog was dead, and that the lion would soon rise and devour him. But they were mistaken. The dog began to move, and struggled to get loose, which the lion permitted him to do. He seemed merely to have warned him not to meddle with him any more; but when the dog attempted to run away, and had already got half over the enclosure, the lion's indignation seemed to be excited. He sprang from the ground, and in two leaps reached the fugitive, who had just got as far as the paling, and was whining to have it opened for him to escape. The flying animal had called the instinctive propensity of the monarch of the forest into action: the defenceless enemy now excited his pity; for the generous lion stepped a few paces backward, and looked quietly on, while a small door was opened to let the dog out of the enclosure.

This unequivocal trait of generosity moved every spectator. A shout of applause resounded throughout the assembly, who had enjoyed a satisfaction of a description far superior to what they had expected.

It is possible that the African lion, when, under the impulse of hunger, he goes out to seek his prey, may not so often exhibit this magnanimous disposition; for in that case he is compelled by imperious necessity to satisfy the cravings of nature; but when his appetite is satiated, he never seeks for prey, nor does he ever destroy to gratify a blood-thirsty disposition.*[3]

A Man killed by a Lion.

Under the reign of Augustus, king of Poland and elector of Saxony, a lion was kept in the menagerie at Dresden, between whom and his attendant such a good understanding subsisted, that the latter used not to lay the food which he brought to him before the grate, but carried it into his cage. Generally the man wore a green jacket; and a considerable time had elapsed, during which the lion had always appeared very friendly and grateful whenever he received a visit from him.

Once the keeper, having been to church to receive the sacrament, had put on a black coat, as is usual in that country upon such occasions, and he still wore it when he gave the lion his dinner. The unusual appearance of the black coat excited the lion's rage; he leapt at his keeper, and struck his claws into his shoulder. The man spoke to him gently, when the well-known tone of his voice brought the lion in some degree to recollection. Doubt appeared expressed in his terrific features; however, he did not quit his hold. An alarm was raised: the wife and children ran to the place with shrieks of terror. Soon some grenadiers of the guard arrived, and offered to shoot the animal, as there seemed, in this critical moment, to be no other means of extricating the man from him; but the keeper, who was attached to the lion, begged them not to do it, as he hoped he should be able to extricate himself at a less expense. For nearly a quarter of an hour, he capitualted with his enraged friend, who still would not let go his hold, but shook his mane, lashed his sides with his tail, and rolled his fiery eyes. At length the man felt himself unable to sustain the weight of the lion, and yet any serious effort to extricate himself would have been at the immediate hazard of his life. He therefore desired the grenadiers to fire, which they did through the grate, and killed the lion on the spot; but in the same moment, perhaps only by a convulsive dying grasp, he squeezed the keeper between his powerful claws with such force, that he broke his arms, ribs, and spine; and they both fell down dead together.*[4]

A Woman killed by a Lion.

In the beginning of the last century, there was in the menagerie at Cassel, a lion that showed an astonishing degree of tameness towards the woman that had the care of him. This went so far, that the woman, in order to amuse the company that came to see the animal, would often rashly place not only her hand, but even her head, between his tremendous jaws. She had frequently performed this experiment without suffering any injury; but having once introduced her head into the lion's mouth, the animal made a sudden snap, and killed her on the spot. Undoubtedly, this catastrophe was unintentional on the part of the lion; for probably at the fatal moment the air of the woman's head irritated the lion's throat, and compelled him to sneeze or cough; at least, this supposition seems to be confirmed by what followed: for as soon as the lion perceived that he had killed his attendant, the good-tempered, grateful animal exhibited signs of the deepest melancholy, laid himself down by the side of the dead body, which he would not suffer to be taken from him, refused to take any food, and in a few days pined himself to death.† [5]

The Lions in the Tower.

Lions, with other beasts of prey and curious animals presented to the king of England, are committed to the Tower on their arrival, there to remain in the custody of a keeper especially appointed to that office by letters patent; he has apartments for himself, with an allowance of sixpence a day, and further sixpence a day for every lion and leopard. Maitland says the office was usually filled by some person of distinction and quality, and he instances the appointment of Robert Marsfield, Esq., in the reign of king Henry VI.* [6] It appears from the patent rolls, that in 1382, Richard II. appointed John Evesham, one of his valets, keeper of the lions, and one of the valets-at-arms in the Tower of London, during pleasure. His predecessor was Robert Bowyer.† [7] Maitland supposes lions and leopards to have been the only beasts kept there for many ages, except a white bear and an elephant in the reign of Henry III. That monarch, on the 26th of February, 1256, honoured the sheriff of London with the following precept:—"The King to the Sheriffs of London, greeting: We command you, that of the farm of our city ye cause, without delay, to be built at our Tower of London one house of forty feet long, and twenty feet deep, for our Elephant." Next year, on the 11th of October, the king in like manner commanded the sheriffs "to find for the said Elephant and his keeper such necessaries as should be reasonable needful." He had previously ordered them to allow fourpence a day for keeping the white bear and his keeper; and the sheriffs were royally favoured with an injunction to provide a muzzle and an iron chain to hold the bear out of the water, and also a long and strong cord to hold him while he washed himself in the Thames.

Stow relates, that James I., on a visit to the lion and lioness in the Tower, caused a live lamb to be put into them; but they refused to harm it, although the lamb in its innocence went close to them. An anecdote equally striking was related to the editor of the Every-Day Book by an individual whose friend, a few years ago, saw a young calf thrust into the den of a lion abroad. The calf walked to the lion, and rubbed itself against him as he lay; the lion looked, but did not move; the calf, by thrusting its nose under the side of the lion, indicated a desire to suck, and the lion then slowly rose and walked away, from mere disinclination to be interfered with, but without the least expression of resentment, although the calf continued to follow him.

On the 13th of August, 1731, a litter of young lions was whelped in the Tower, from a lioness and lion whelped there six years before. In the Gentleman's Magazine for February, 1739, there is an engraving of Marco, a lion then in the Tower.

On the 6th of April, 1775, a lion was landed at the Tower, as a present to his late majesty from Senegal. He was taken in the woods, out of a snare, by a private soldier, who, being attacked by two natives that had laid it, killed them both, and brought away the lion. The king ordered his discharge for this act, and further rewarded him by a pension of fifty pounds a year for life. On this fact, related in the Gentleman's Magazine for that year, a correspondent inquires of Mr. Urban whether "a lion's whelp is an equivalent for the lives of two human creatures." To this question, reiterated by another, it is answered in the same volume, with rectitude of principle and feeling, that "if the fact be true, the person who recommended the soldier to his majesty's notice, must have considered the action in a military light only, and must totally have overlooked the criminality of it in a moral sense. The killing two innocent fellow-creatures, unprovoked, only to rob them of the fruits of their ingenuity, can never surely be accounted meritorious in one who calls himself a christian. If it is not meritorious, but contrary, the murderer was a very improper object to be recommended as worthy to be rewarded by a humane and christian king." This settled the question, and the subject was not revived.

THE LION'S HEAD.

Because the inundation of the Nile happened during the progress of the sun in Leo, the ancients caused the water of their fountains to issue from the mouth of a lion's head, sculptured in stone. The circumstance is pleasant to notice at this season; a few remarks will be made on fountains by-and-bye.

The Lion's Head, at Button's coffee-house, is well remembered in litrary annals. It was a carving with an orifice at the mouth, through which communications for the "Guardian" were thrown. Button had been a servant in the countess of Warwick's family, and by the patronage of Addison, kept a coffee-house on the south side of Russell-street, about two doors from Covent-garden, where the wits of that day used to assemble. Addison studied all the morning, dined at a tavern, and afterwards went to Button's. "The Lion's Head" was inscribed with two lines from Martial:—

Cervantur magnis isti Cervicibus ungues:

Non nisi delecta pascitur ille fera.This has been translated in the Gentleman's Magazine thus:—

Bring here nice morceaus; be it understood

The lion vindicates his choicest food.Button's "Lion's Head" was afterwards preserved at the Shakspeare Tavern, where it was sold by auction on the 8th of November, 1804, to Mr. Richardson of the Grand Hotel, the indefatigable collector and possessor of an immense mass of materials for the history of St. Paul, Covent-garden, the parish wherein he resides. The late duke of Norfolk was his ineffectual competitor at the sale: the noble peer suffered the spirited commoner to gain the prize for 17l. 10s. Subsequently the duke frequently dined at Mr. Richardson's, whom he courted in vain to relinquish the gem. Mr. R. had the head with its inscription handsomely engraved for his "great seal," from which he has caused delicate impressions to be presented in oak-boxes, to a few whom it has pleased him so to gratify; and among them the editor of the Every-Day Book, who thus acknowledges the acceptable civility.

In the London Magazine the "Lion's Head," fronts each number, greeting its correspondents, and others who expect announcements, with "short affable roars," and inviting "communications" from all "who may have committed a particularly good action, or a particularly bad one—or said or written any thing very clever, or very stupid, during the month." By too literal a construction of this comprehensive invitation, some got into the "head," who, not having reach enough for the "body" of the magazine, were happy to get out with a slight scratch, and others remain without daring to say "their souls are their own"—to the re-reformation of themselves, and as examples to others contemplating like offences. The "Lion" of the "London" is of delicate scent, and shows high masterhood in the great forest of literature.

St. Anne.

Her name, which in Hebrew signifies gracious, is in the church of England calendar and almanacs on this day, which is kept as a great holiday by the Romish church.

The history of St. Anne is an old fiction. It pretends that she and her husband Joachim were Jews of substance, and lived twenty years without issue, when the high priest, on Joachim making his offerings in the temple, at the feast of the dedication, asked him why he, who had no children, presumed to appear among those who had; adding, that his offerings were not acceptable to God, who had judged him unworthy to have children, nor, until he had, would his offerings be accepted. Joachim retired, and bewailed his reproach among his shepherds in the pastures without returning home, lest his neighbours also should reproach him. The story relates that, in this state, an angel appeared to him and consoled him, by assuring him that he should have a daughter, who should be called Mary, and for a sign he declared that Joachim on arriving at the Golden Gate of Jerusalem should there meet his wife Anne, who being very much troubled that he had not returned sooner, should rejoice to see him. Afterwards the angel appeared to Anne, who was equally disconsolate, and comforted her by a promise to the same effect, and assured her by a like token, namely, that at the Golden Gate she should meet her husband for whose safety she had been so much concerned. Accordingly both of them left the places where they were, and met each other at the Golden Gate, and rejoiced at each others' vision, and returned thanks, and lived in cheerful expectation that the promise would be fulfilled.

The meeting between St. Anne and St. Joachim at the Golden Gate was a favourite subject among catholic painters, and there are many prints of it. From one of them in the "Salisbury Missal," (1534 fo. xix) the annexed engraving is copied. The curious reader will find notices of others in a volume on the "Ancient Mysteries," by the editor of the Every-Day Book. The wood engraving in the "Missal" is improperly placed there to illustrate the meeting between the Virgin Mary and Elizabeth.

Meeting of St. Anne and St. Joachim

AT THE GOLDEN GATE.

It is further pretended, that the result of the angel's communication to Joachim and Anne was the miraculous birth of the Virgin Mary, and that she was afterwards dedicated by Anne to the service of the temple, where she remained till the time of her espousal by Joseph.

In the Romish breviary of Sarum there are forms of prayer to St. Anne, which show how extraordinarily highly these stories placed her. One of them is thus translated by bishop Patrick:*[8]

"O vessel of celestial grace,

Blest mother to the virgins' queen,

By thee we beg, in the first place,

Remission of all former sin."Great mother, always keep in mind

The power thou hast, by thy sweet daughter,

And, by thy wonted prayer, let's find

God's grace procur'd to us hereafter."Another, after high commendations to St. Anne, concludes thus:—

"Therefore, still asking, we remain,

And thy unwearied suitors are,

That, what thou canst, thou wouldst obtain,

And give us heaven by thy prayer.

Do thou appease the daughter, thou didst bear,

She her own son, and thou thy grandson dear."The nuns of St. Anne at Rome show a rude silver ring as the wedding-ring of Anne and Joachim; both ring and story are ingenious fabrications. There are of course plenty of her relics and miracles from the same sources. They are further noticed in the work on the "Mysteries" referred to before.

SUMMER HOLIDAYS.

A young, and not unknown correspondent of the Every-Day Book, has had a holiday—his first holiday since he came to London, and settled down into an every-day occupation of every hour of his time. He seems until now not to have known that the environs of London abound in natural as well as artifical beauties. What he has seen will be productive of this advantage; it will induce residents in London, who never saw Dulwich, to pay it a visit, and see all that he saw. Messrs. Colnaghi and Son, of Pall-mall East, Mr. Clay of Ludgate-hill, or any other respectable printseller, will supply an applicant with a ticket of admission for a party, to see the noble gallery of pictures there. These tickets are gratuitous, and a summer holiday may be delightfully spent by viewing the paintings, and walking in the pleasant places adjacent: the pictures will be agreeable topics for conversation during the stroll.

MY HOLIDAY!

To the Editor of the Every-Day Book.

My dear Sir,

The kind and benevolent feelings which you are so wont to discover, and the sparkling good-humour and sympathy which characterize your Every-Day Book, encourage me to describe to you "My holiday!" I approach you with familiarity, being well known as your constant reader. You also know me to be a provincial cockney—a transplant. Oh! why then do you so often paint nature in her enchanting loveliness? What cruelty! You know my destiny is foreign to my desires: I cannot now seek the shade of a retired grove, carelessly throw myself on the bank of a "babbling brook," there muse and angle, as I was wont to do, and, as my old friend Izaak Walton bade me,—"watch the sun to rise and set,

There meditate my time away,

And beg to have a quiet passage to a welcome grave."But, I have had a holiday! The desk was forsaken for eight-and-forty hours! Think of that! I have experienced what Leigh Hunt desires every christian to experience—that there is a green and gay world, as well as a brick and mortar one. Months previous was the spot fixed upon which was to receive my choice, happy spirit. Dulwich was the place. It was an easy distance from town; moreover, it was a "rustic" spot; moreover, it had a picture-gallery; in a word, it was just the sort of place for me. The happy morning dawned, I could say with Horace, with the like feelings of enraptured delight—

"Insanire juvat. Sparge rosas."

Such was the disposition of my mind.

We met (for I was accompanied) at that general rendezvous for carts, stages, waggons, and sociables, the Elephant and Castle. There were the honest, valiant, laughter-loving J—; the pensive, kindly-hearted G—; and the sanguine, romantic, speculative M—. A conveyance was soon sought. It was a square, covered vehicle, set on two wheels, drawn by one horse, which was a noble creature, creditable to its humane master, who has my best wishes, as I presume he will never have cause to answer under Mr. Martin's Act. Thus equipaged and curtained in, we merrily trotted by the Montpelier Gardens, and soon overtook the "Fox-under-the-Hill." To this "Fox" I was an entire stranger, having never hunted in the part of the country before. The beautiful hill which brought us to the heights of Camberwell being gained, we sharply turned to the left, which gave us the view of Dulwich and its adjoining domains in the distance. Oh, ecstacy of thought! Gentle hills, dark valleys, far-spreading groves, luxuriant corn-fields, magnificent prospects, then sparkled before me. The rich carpet of nature decked with Flora's choicest flowers, and wafting perfumes of odoriferous herbs floating on the breezes, expanded and made my heart replete with joy. What kind-heartedness then beamed in our countenances! We talked, and joked, and prattled; and so fast did our transports impulse, that to expect an answer to one of my eager inquiries as to "who lives here or there?" was out of the question. Our hearts were redolent of joy. It was our holiday!

By the side of the neat, grassy, picturesque burying-ground we alighted, in front of Dulwich-college. Now for the picture-gallery. Some demur took place as to the safety of the "ticket." After a few moments' intense anxiety, it appeared. How important was that square bit of card!—it was the key to our hopes—"Admit Mr. R— and friends to view the Bourgeois Gallery." We entered by the gate which conducts into the clean, neat, and well-paved courtyard contiguous to the gallery. In the lodge, which is situate at the end of this paved footpath, you see a comely, urbane personage. With a polite bend of the head, and a gentle smile of good-nature on his countenance on the production of the "ticket," he bids you welcome. The small folding doors on your right hand are then opened, and this magnificent gallery is before you. This collection is extremely rich in the works of the old masters, particularly Poussin, Teniers, Vandyke, Claude, Rubens, Cuype, Murillo, Velasquez, Annibal Caracci, Vandervelt, Vanderwerf, and Vanhuysem. Here I luxuriated. With my catalogue in hand, and the eye steadily fixed upon the subject, I gazed, and although neither connoisseur nor student, felt that calmness, devotion, and serenity of soul, which the admiration of either the works of a poet, or the "sweet harmony" of sound, or form, alone work upon my heart. I love nature, and here she was imitated in her simplest and truest colourings. The gallery, or rather the five elegant rooms, are well designed, and the pictures admirably arranged. We entered by a door about midway in the gallery, on the left. and were particularly pleased with the mausoleum. The design is clever and ingenious, and highly creditable to the talents of Mr. Soane. Here lie sir Francis Bourgeois, and Mr. and Mrs. Desefans, surrounded by these exquisite pictures. The masterly painting of the Death of Cardinal Beaufort is observed nearly over this entrance-door. But, time hastens—and after noticing yonder picture which hangs at the farther extremity of the gallery, I will retire. It is the Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, by Annibal Caracci. Upon this sublime painting I could meditate away an age. It is full of power, of real feeling and poetry. Mark that countenance—the uplifted eye "with holy fervour bright!"—the resignation, calmness, and holy serenity, which speak of truth and magnanimity, contrasted with the physical sufferings and agonies of a horrid death. I was lost—my mind was slumbering on this ocean of sublimity!

The lover of rural sights will return from Dulwich-college by the retired footpath that strikes off to the right by the "cage" and "stocks" opposite the burying-ground. On ascending the verdant hill which leads to Camberwell Grove, the rising objects that gradually open to the view are most beautifully picturesque and enchanting. We reached the summit of the Five Fields:—

"Heav'ns! what a goodly prospect spread around

Of hills, and dales, and woods, and lawns, and spires,

And glittering towns, and gilded streams."This is a fairy region. The ravished eye glances from villa to grove, turret, pleasure-ground, hill, dale; and "figured streams in waves of silver" roll. Here are seen Norwood, Shooter's-hill, Seven Droog Castle, Peckham, Walworth, Greenwich, Deptford, and bounding the horizon, the vast gloom of Epping Forest. What a holiday! What a feast for the mind, the eye, and the heart! A few paces from us we suddenly discerned a humble, aged wintry object, sitting as if in mockery of the golden sunbeam which played across his furrowed cheek. The philanthropy of the good and gentle Elia inspired our hearts on viewing this "dim speck," this monument of days gone by. Love is charity, and it was charitable thus to love. The good old patriarch asked not, but received alms with humility and gratitude. His poverty was honourable: his character was noble and elevated in lowliness. He gracelessly doffed his many-coloured cap in thanks (for hat he had none), and the snowy locks floating on the breeze rendered him an object as interesting as he was venerable. Could we have made all sad hearts gay, we should but have realized the essayings of our souls. Our imaginings were of gladness and of joy. It was our holiday!

Now, my holiday is past! Hope, like a glimmering star, appears to me through the dark waves of time, and is ominous of future days like these. We are now "at home," homely in use as occupation. I am hugging the desk, and calculating. I can now only request others who have leisure and opportunity to take a "holiday," and make it a "holiday" similar to this. Health will be improved, the heart delighted, and the mind strengthened. The grovelling sensualist, who sees pleasure only in confusion, never can know pleasures comparable with these. There is a moral to every circumstance of life. One may be traced in the events of "My holiday!"

I am, dear Sir,

Yours very truly,

S. R.

WEATHER.

To the Editor of the Every-Day Book.

Sir,

The subjoined table for foretelling weather, appears strictly within the plan of the Every-Day Book, for who that purposes out-door recreation, would not seize the probability of fixing on a fine day for the purpose; or what agriculturist would decline information that I venture to affirm may be relied on? It is copied from the Rev. Dr. Adam Clarke. (See the "Wesleyan Methodist Magazine," New Series, vol. iii., p. 457, 458.) Believing that it will be gratifying and useful to your readers,I am, &c.,

O. F. S.Doctors Commons.

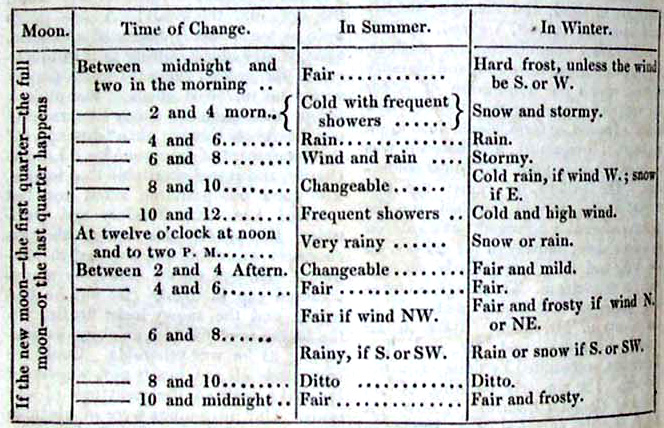

THE WEATHER PROGNOSTICATOR

Through all the Lunations of each Year for ever.

This table and the accompanying remarks are the result of many years' actual observation; the whole being constructed on a due consideration of the attraction of the sun and moon in their several positions respecting the earth; and will, by simple inspection, show the observer what kind of weather will most probably follow the entrance of the moon into any of her quarters, and that so near the truth is to be seldom found to fail.

OBSERVATIONS.

1. The nearer the time of the moon's change, first quarter, full, and last quarter, is to midnight, the fairer will the weather be during the seven days following.

2. The space for this calculation occupies from ten at night till two next morning.

3. The nearer to mid-day or noon these phases of the moon happen, the more foul or wet the weather may be expected during the next seven days.

4. The space for this calculation occupies from ten in the forenoon to two in the afternoon. These observations refer principally to summer, though they affect spring and autumn nearly in the same ratio.

5. The moon's change—first quarter—full—and last quarter, happening during six of the afternoon hours, i. e. from four to ten, may be followed by fair weather: but this is mostly dependent on the wind, as it is noted in the table.

6. Though the weather, from a variety of irregular causes, is more uncertain in the latter part of autumn, the whole of winter, and the beginning of spring; yet, in the main, the above observations will apply to those periods also.

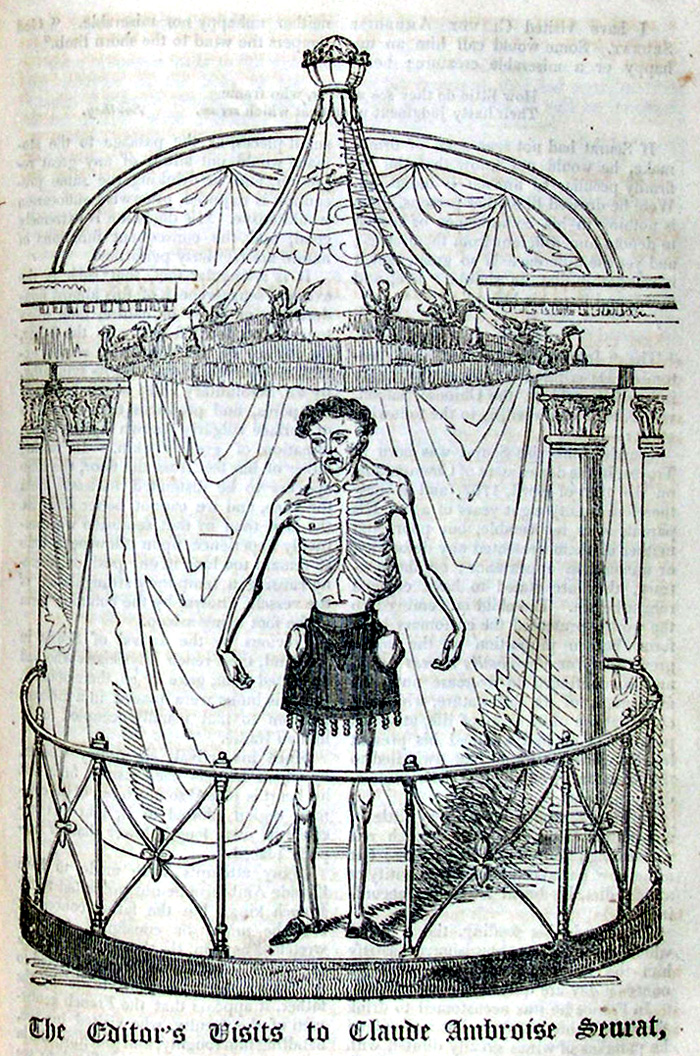

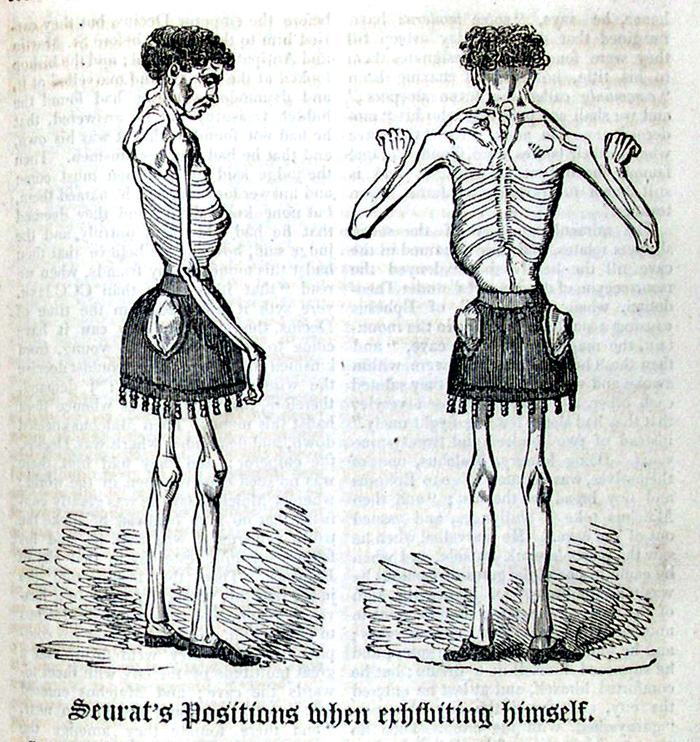

The Editor's Visits to Claude Ambroise Seurat,

EXHIBITED IN PALL MALL UNDER THE APPELLATION OF THE

ANATOMIE VIVANTE; or, LIVING SKELETON!