May 30.

St. Felix I., Pope, A.D. 274. St. Walstan, Confessor, A.D. 1016. St. Ferdinand III., Confessor, King of Castile and Leon, A.D. 1252. St. Maguil, in Latin, Madelgisilus, Recluse in Picardy, about A.D. 685.

Trinity Monday.

Deptford Fair.

Of late years a fair has been held at Deptford on this day. It originated in trifling pastimes for persons who assembled to see the master and brethren of the Trinity-house, on their annual visit to the Trinity-house, at Deptford. First there were jingling matches; then came a booth or two; afterwards a few shows; and, in 1825, it was a very considerable fair. There were Richardson's, and other dramatic exhibitions; the Crown and Anchor booth, with a variety of dancing and drinking booths, as at Greenwich fair this year, before described, besides shows in abundance.

Brethren of the Trinity-house.

This maritime corporation, according to their charter, meet annually on Trinity Monday, in their hospital for decayed sea-commanders and their widows at Deptford, to choose and swear in a master, wardens, and other officers, for the year ensuing. The importance of this institution to the naval interests of the country, and the active duties required of its members, are of great magnitude, and hence the master has usually been a nobleman of distinguished rank and statesman-like qualities, and his associates are always experienced naval officers: of late years lord Liverpool has been master. The ceremony in 1825 was thus conducted. The outer gates of the hospital were closed against strangers, and kept by a party of the hospital inhabitants; no person being allowed entrance without express permission. By this means the large and pleasant court-yard formed by the quadrangle, afforded ample accomodation to ladies and other respectable persons. In the mean time, the hall on the east side was under preparation within, and the door strictly guarded by constables stationed without; an assemblage of well-dressed females and their friends, agreeably diversified the lawn. From eleven until twelve o'clock, parties of two or three were so fortunate as to find favour in the eyes of Mr. Snaggs, the gentleman who conducted the arrangements, and gained entrance. The hall is a spacious handsome room, wherein divine service is performed twice a-week, and public business, as on this occasion, transacted within a space somewhat elevated, and railed off by balustrades. On getting within the doors, the eye was struck by the unexpected appearance of the boarded floor; it was strewed with green rushes, the use of which by our ancestors, who lived before floors were in existence, is well known. The reason for continuing the practice here, was not so apparent as the look itself was pleasant, by bringing the simple mannters of other times to recollection. At about one o'clock, the sound of music having announced that lord Liverpool and his associate brethren had arrived within the outer gate, the hall doors were thrown open, and the procession entered. His lordship wore the star of the garter on a plain blue coat, with scarlet collar and cuffs, which dress, being the Windsor uniform, was also worn by the other gentlemen. They were preceded by the rev. Dr. Spry, late of Birmingham, now of Langham church, Portland-place, in full canonicals. After taking their seats at the great table within the balustrades, it was proclaimed, that this being Trinity Monday, and therefore, according to the charter, the day for electing the master, deputy-master, and elder brethren of the holy and undivided Trinity, the brethren were required to proceed to the election. Lord Liverpool, being thereupon nominated master, was elected by a show of hands, as were his coadjutors in like manner. The election concluded, large silver and silver-gilt cups, richly embossed and chased, filled with cool drink, were handed round; and the doors being thrown open, and the anxious expectants outside allowed to enter, the hall was presently filled, and a merry scene ensued. Large baskets filled with biscuits were laid on the table before the brethren; Lord Liverpool then rose, and throwing a biscuit into the middle of the hall, his example was followed by the rest of the brethren. Shouts of laughter arose, and a general scramble took place. This scene continued about ten minutes, successive baskets being brought in and thrown among the assembly, until such as chose to join in the scramble were supplied; the banner-bearers of the Trinity-house, in their rich scarlet dresses and badges, who had accompanied the procession into the hall, increased the merriment by their superior activity. A procession was afterwards formed, as before, to Deptford old church, where divine service was performed, and Dr. Spry being appointed to preach before the brethren, he delivered a sermon from Psalm cxlv. 9. "the Lord is good to all, and his tender mercies are over all his works." The discourse being ended, the master and brethren returned in procession to their state barges, which lay at the stairs of Messrs. Gordon & Co., anchorsmiths. They were then rowed back to the Tower, where they had embarked, in order to return to the Trinity-house from whence they had set out. Most of the vessels in the river hoisted their colours in honour of the corporation, and salutes were fired from different parts on shore. The Trinity-yacht, which lay off St. George's, near Deptford, was completely hung with the colours of all nations, and presented a beautiful appearance. Indeed the whole scene was very delightful, and created high feelings in those who recollected that to the brethren of the Trinity are confided some of the highest functions that are exercised for the protection of life and property on our coasts and seas.

To the Editor of the Every-Day Book.

Dear Sir,

Though I have not the pleasure of a personal acquaintance, I know enough to persuade me that you are no every-day body. The love of nature seems to form so prominent a trait in your character, that I, who am also one of her votaries, can rest no longer without communicating with you on the subject. I like, too, the sober and solitary feeling with which you ruminate over by-gone pleasures, and scenes wherein your youth delighted: for, though I am but young myself, I have witnessed by far too many changes, and have had cause to indulge too frequently in such cogitations.

I am a "Surrey-man," as the worthy author of the "Athenæ Oxon." would say: and though born with a desire to ramble, and a mind set on change, I have never till lately had an opportunity of strolling so far northward as "ould Iselton," or "merry Islington:"—you may take which reading you please, but I prefer the first. But from the circumstance of your "walk out of London" having been directed that way, and having led you into so pleasant a mood, I am induced to look for similar enjoyment in my rambling excursions through its "town-like" and dim atmosphere. I am not ashamed to declare, that my taste in these matters differs widely from that of the "great and good" Johnson; who, though entitled, as a constellation of no ordinary "brilliance," to the high sounding name of "the Great Bear," (which I am not the first to appropriate to him,) seems to have set his whole soul on "bookes olde," and "modern authors" of every other description, while the book of nature, which was schooling the negro-wanderer of the desert, proffered nothing to arrest his attention! Day unto day was uttering speech, and night unto night showing knowledge; the sun was going forth in glory, and the placid moon "walking in brightness;" and could he close his ears, and revert his gaze?—"De gustibus nil disputandum" I cannot say, for I do most heartily protest against his taste in such matters.

"The time of the singing of birds is come," but, what is the worst of it, all these "songsters" are not "feathered." There is a noted "Dickey" bird, who took it into his head, so long ago as the 25th of December last, to "sing through the heavens,"*[1] —but I will have nothing to do with the "Christemasse Caroles" of modern day. Give me the "musical pyping" and "pleasaunte songes" of olden tyme, and I care not whether any more "ditees" of the kind are concocted till doomsday.

But I must not leave the singing of birds where I found it: I love to hear the nightingales emulating each other, and forming, by their "sweet jug jug," a means of communication from one skirt of the wood to the other, while every tree seems joying in the sun's first rays. There is such a wildness and variety in the note, that I could listen to it, unwearied, for hours. The dew still lies on the ground, and there is a breezy freshness about us: as our walk is continued, a "birde of songe, and mynstrell of the woode," holds the tenor of its way across the path:—but it is no "noiseless tenor." "Sweet jug, jug, jug," says the olde balade:—

"Sweet jug, jug, jug,

The nightingale doth sing,

From morning until evening,

As they are hay-making."Was this "songe" put into their throats "aforen yt this balade ywritten was?" I doubt it, but in later day Wordsworth and Conder have made use of it; but they are both poets of nature, and might have fancied it in the song itself.

I look to my schoolboy days as the happiest I ever spent: but I was never a genius, and laboured under habitual laziness, and love of ease: "the which," as Andrew Borde says, "doth much comber young persones." I often rose for a "lark," but seldom with it, though I have more than once "cribbed out" betimes, and always found enough to reward me for it. But these days are gone by, and you will find below all I have to say of the matter "collected into English metre:"—

Years of my boyhood! have you passed away?

Days of my youth and have you fled for ever?

Can I but joy when o'er my fancy stray

Scenes of young hope, which time has failed to sever

From this fond heart:—for, tho' all else decay,

The memory of those times will perish never.—

Time cannot blight it, nor the tooth of care

Those wayward dreams of joyousness impair.Still, with the bright May-dew, the grass is wet;

No human step the slumbering earth has prest:

Cheering as hope, the sun looks forth; and yet

There is a weight of sorrow on my breast:

Life, light, and joy, his smiling beams beget,

But yield they aught, to soothe a mind distrest;

Can the heart, cross'd with cares, and born to sorrow,

From Nature's smiles one ray of comfort borrow!But I must sympathize with you in your reflections, amid those haunts which are endeared by many a tie, on the decay wrought by time and events. An old house is an old friend; a dingy "tenement" is a poor relation, who has seen better days; "it looks, as it would look its last," on the surrounding innovations, and wakes feelings in my bosom which have no vent in words. Its "imbowed windows," projecting each story beyond the other, go to disprove Bacon's notion, that "houses are made to live in, and not to look on:" they give it a brow-beating air, though its days of "pomp and circumstance" are gone by, and have left us cheerlessly to muse and mourng over its ruins:—

Oh! I can gaze, and think it quite a treat,

So they be old, on buildings grim and shabby;

I love within the church's walls to greet

Some "olde man" kneeling, bearded like a rabbi,

Who never prayed himself, but has a whim

That you'll "orate," that is—"praye" for him.But this has introduced me to another and an equally pleasing employ; that of traversing the aisles of our country churches, and "meditating among the tombs." I dare not go farther, for I am such an enthusiast, that I shall soon write down your patience.

You expressed a wish for my name and address, on the cover of your third part; I enclose them: but I desire to be known to the public by no other designation than my old one.

I am, dear sir,

Yours, &c.

LECTOR.Camberwell.

CHRONOLOGY .

1431. Joan of Arc, the maid of Orleans was burnt. This cruel death was inflicted on her, in consequence of the remarkable events hereafter narrated. Her memory is revered by Frenchmen, and rendered more popular, through a poem by Voltaire, eminent for its wit and licentiousness. One of our own poets, Dr. Southey, has an epic to her honour.

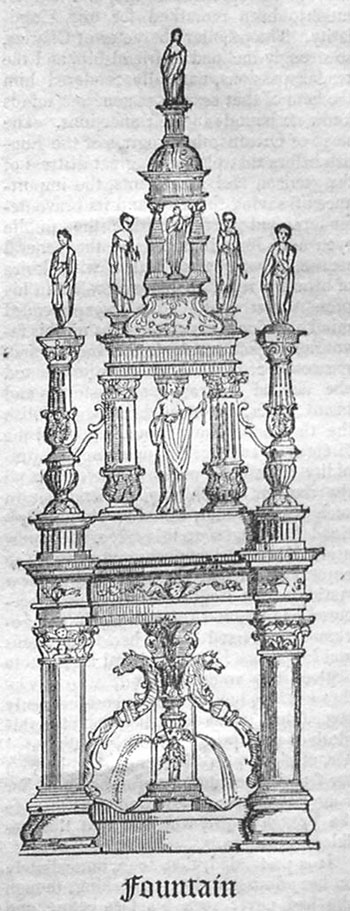

Fountain

Erected in the old Market-place at Rouen, on the spot whereon

Joan of Arc

WAS BURNT.

In the petty town of Neufchateau, on the borders of Lorraine, there lived a country girl of twenty-seven years of age, called Joan d'Arc. She was servant in a small inn, and in that station had been accustomed to ride the horses of the guests, without a saddle, to the watering-place, and to perform other offices, which, in well-frequented inns, commonly fall to the share of the men-servants. This girl was of an irreproachable life, and had not hitherto been remarked for any singularity. The peculiar character of Charles, so strongly inclined to friendship, and the tender passions, naturally rendered him the hero of that sex whose generous minds know no bounds in their affections. The siege of Orleans, the progress of the English before that place, the great distress of the garrison and inhabitants, the importance of saving this city, and its brave defenders, had turned thither the public eye; and Joan, inflamed by the general sentiment, was seized with a wild desire of bringing relief to her sovereign in his present distresses. Her unexperienced mind, working day and night on this favourite object, mistook the impulses of passion for heavenly inspirations; and she fancied that she saw visions, and heard voices, exhorting her to reestablish the throne of France, and to expel the foreign invaders. An uncommon intrepidity of temper, made her overlook all the dangers which might attend her in such a path; and, thinking herself destined by heaven to this office, she threw aside all that bashfulness and timidity so natural to her sex, her years, and her low station. She went to Vaucouleurs; procured admission to Baudricourt, the governor; informed him of her inspirations and intentions; and conjured him not to neglect the voice of God, who spoke through her, but to second those heavenly revelations which impelled her to this glorious enterprise. Baudricourt treated her, at first, with some neglect; but, on her frequent returns to him, he gave her some attendants, who conducted her to the French court, which at that time resided in Chinon.

It is pretended, that Joan, immediately on her admission, knew the king, though she had never seen his face before, and though he purposely kept himself in the crowd of courtiers, and had laid aside every thing in his dress and apparel which might distinguish him: that she offered him, in the name of the supreme Creator, to raise the siege of Orleans, and conduct him to Rheims, to be there crowned and anointed: and, on his expressing doubts of her mission, revealed to him, before some sworn confidants, a secret, which was unknown to all the world beside himself, and which nothing but a heavenly inspiration could have discovered to her: and that she demanded, as the instrument of her future victories, a particular sword, which was kept in the church of St. Catherine of Fierbois, and which, through she had never seen it, she described by all its marks, and by the place in which it had long lain neglected. This is certain, that all these miraculous stories were spread abroad, in order to captivate the vulgar. The more the king and his ministers were determined to give in to the illusion, the more scruples they pretended. An assembly of grave doctors and theologians cautiously examined Joan's mission, and pronounced it undoubted and supernatural. She was sent to the parliament, then at Poictiers, who became convinced of her inspiration. A ray of hope began to break through that despair in which the minds of all men were before enveloped. She was armed cap-a-pee, mounted on horseback, and shown in that martial habiliment before the whole people.

Joan was sent to Blois, where a large convoy was prepared for the supply of Orleans, and an army of ten thousand men, under the command of St. Severe, assembled to escort it; she ordered all the soldiers to confess themselves before they set out on the enterprise; and she displayed in her hands a consecrated banner, whereon the Supreme Being was represented, grasping the globe of earth, and surrounded with flower-de-luces.

The English affected to speak with derision of the maid, and of her heavenly commission; and said, that the French king was now indeed reduced to a sorry pass, when he had recourse to such ridiculous expedients. As the convoy approached the river, a sally was made by the garrison on the side of Beausse, to prevent the English general from sending any detachment to the other side: the provisions were peaceably embarked in boats, which the inhabitants of Orleans had sent to receive them: the maid covered with her troops the embarkation: Suffolk did not venture to attack her; and Joan entered the city of Orleans arrayed in her military garb, and displaying her consecrated standard. She was received as a celestial deliverer by all the inhabitants, who now believed themselves invincible under her influence. Victory followed upon victory, and the spirit resulting from a long course of uninterrupted success was on a sudden transferred from the conquerors to the conquered. The maid called aloud, that the garrison should remain no longer on the defensive. The generals seconded her ardour: an attack was made on the English intrenchments, and all were put to the sword, or taken prisoners. Nothing, after this success, seemed impossible to the maid and her enthusiastic votaries; yet, in one attack, the French were repulsed; the maid was left almost alone; she was obliged to retreat; but displaying her sacred standard, she led them back to the charge, and overpowered the English in their intrenchments. In the attack of another fort, she was wounded in the neck with an arrow; she retreated a moment behind the assailants; pulled out the arrow with her own hands; had the wound quickly dressed; hastened back to head the troops; planted her victorious banner on the ramparts of the enemy; returned triumphant over the bridge, and was again received as the guardian angel of the city. After performing such miracles, it was in vain even for the English generals to oppose with their soldiers the prevailing opinion of supernatural influence: the utmost they dared to advance was, that Joan was not an instrument of God, but only the implement of the devil. In the end the siege of Orleans was raised, and the English thought of nothing but of making their retreat, as soon as possible, into a place of safety; while the French esteemed the overtaking them equivalent to a victory. So much had the events which passed before this city altered every thing between the two nations! The raising of the siege of Orleans was one part of the maid's promise to Charles: the crowning of him at Rheims was the other: and she now vehemently insisted that he should forthwith set out on that enterprise. A few weeks before, such a proposal would have appeared the most extravagant in the world. Rheims lay in a distant quarter of the kingdom; was then in the hands of a victorious enemy; the whole road which led to it was occupied by their garrisons; and no man could be so sanguine as to imagine that such an attempt could so soon come within the bounds of possibility. The enthusiasm and influence of Joan prevailed over all obstacles. Charles set out for Rheims at the head of twelve thousand men: he passed Troye, which opened its gates to him: Chalons imitated the example: Rheims sent him a deputation with its keys, before his approach to it; and the ceremony of his coronation was there performed, with the maid of Orleans by his side in complete armour, displaying her sacred banner, which had so often dissipated and confounded his fiercest enemies. The people shouted with unfeigned joy on viewing such a complication of wonders, and after the completion of the ceremony, the maid threw herself at the king's feet, embraced his knees, and with a flood of tears, which pleasure and tenderness extorted from her, she congratulated him on this singular and marvellous event.

The duke of Bedford, who was regent during the minority of Henry VI., endeavoured to revive the declining state of his affairs by bringing over the young king of England, and having him crowned and anointed at Paris. The maid of Orleans, after the coronation of Charles, declared to the count of Dunois, that her wishes were now fully gratified, and that she had no farther desire than to return to her former condition and to the occupation and course of life which became her sex: but that nobleman, sensible of the great advantages which might still be reaped from her presence in the army, exhorted her to persevere, till, by the final expulsion of the English, she had brought all her prophecies to their full completion. In pursuance of this advice, she threw herself into the town of Compiegne, which was at that time besieged by the duke of Burgundy, assisted by the earls of Arundel and Suffolk; and the garrison, on her appearance, believed themselves thenceforth invincible. But their joy was of short duration. The maid, next day after her arrival (25th of May,) headed a sally upon the quarters of John of Luxembourg; she twice drove the enemy from their intrenchments; finding their numbers to increase every moment, she ordered a retreat; when hard pressed by the pursuers, she turned upon them, and made them again recoil; but being here deserted by her friends, and surrounded by the enemy, she was at last, after exerting the utmost valour, taken prisoner by the Burgundians. The common opinion was, that the French officers, finding the merit of every victory ascribed to her, had, in envy to her renown, by which they themselves were so much eclipsed, willingly exposed her to this fatal accident.

A complete victory would not have given more joy to the English and their partisans. The service of Te Deum, which has so often been profaned by princes, was publicly celebrated on this fortunate event at Paris. The duke of Bedford fancied, that, by the captivity of that extraordinary woman, who had blasted all his successes, he should again recover his former ascendant over France; and, to push farther the present advantage, he purchased the captive from John of Luxembourg, and formed a prosecution against her, which, whether it proceeded from vengeance or policy, was equally barbarous and dishonourable. It was contrived, that the bishop of Beauvais, a man wholly devoted to the English interest, should present a petition against Joan, on pretence that she was taken within the bounds of his diocese; and he desired to have her tried by an ecclesiastical court, for sorcery, impiety, idolatry, and magic. The university of Paris was so mean as to join in the same request: several prelates, among whom the cardinal of Winchester was the only Englishman, were appointed her judges: they held their court at Rouen, where the young king of England then resided: and the maid, clothed in her former military apparel, but loaded with irons, was produced before this tribunal. Surrounded by inveterate enemies, and brow-beaten and overawed by men of superior rank, and men invested with the ensigns of a sacred character, which she had been accustomed to revere, felt her spirit at last subdued; Joan gave way to the terrors of that punishment to which she was sentenced. She declared herself willing to recant; acknowledged the illusion of those revelations which the church had rejected; and promised never more to maintain them. Her sentence was mitigated: she was condemned to perpetual imprisonment, and to be fed during life on bread and water. But the barbarous vengeance of Joan's enemies was not satisfied with this victory. Suspecting that the female dress, which she had now consented to wear, was disagreeable to her, they purposely placed in her apartment a suit of men's apparel, and watched for the effects of that temptation upon her. On the sight of a dress in which she had acquired so much renown, and which, she once believed, she wore by the particular appointment of heaven, all her former ideas and passions revived; and she ventured in her solitude to clothe herself again in the forbidden garment. Her insidious enemies caught her in that situation: her fault was interpreted to be no less than a relapse into heresy: no recantation would now suffice, and no pardon could be granted her. She was condemned to be burned in the market-place of Rouen, and the infamous sentence was accordingly executed. This admirable heroine, to whom the more generous superstition of the ancients would have erected altars, was, on pretence of heresy and magic, delivered over alive to the flames, and expiated, by that dreadful punishment, the signal services which she had rendered to her native country. To the eternal infamy of Charles and his adherents, whom she had served and saved, they made not a single effort, either by force or negociation, to save this heroic girl from the cruel death to which she had been condemned. Hume says she was burnt on the 14th of June. According to Lingard she perished on the 30th of May.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Lesser Spearwort[.] Ranunculus flammula.

Dedicated to St. Ferdinand.