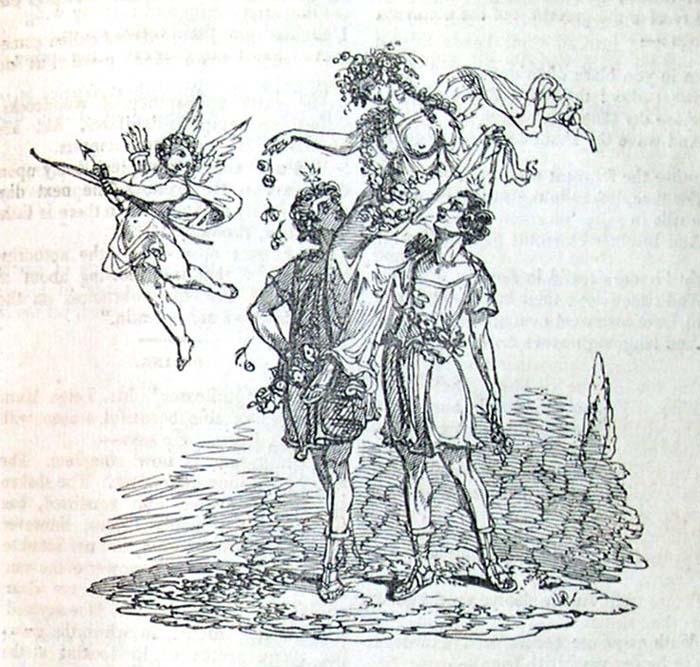

MAY.Then came faire MAY, the fayrest mayd on ground,

Deckt all with dainties of her seasons pryde,

And throwing flow'res out of her lap around:

Upon two brethren's shoulders she did ride,

The twinnes of Leda; which on either side

Supported her, like to their soveraine Queene.

Lord! how all creatures laught, when her they spide,

And leapt and daunc't as they had ravisht beene!

And Cupid Selfe about her fluttred all in greene.

Spenser.

So hath "divinest Spenser" represented the fifth month of the year, in the grand pageant which, to all who have seen it, is still present; for neither the laureate's office nor the poet's art hath devised a spectacle more gorgeous. Castor and Pollux, "the twinnes of Leda," who appeared to sailors in storms with lambent fires on their heads, mythologists have constellated in the firmament, and made still propitious to the mariner. Maia, the brightest of the Pleiades, from whom some say this month derived its name, is fabled to have been the daughter of Atlas, the supporter of the world, and Pleione, a sea-nymph. Others ascribe its name to its having been dedicated by Romaius to the Majores, or Roman senators.

Verstegan affirms of the Anglo-Saxons, that "the pleasant moneth of May they termed by the name of Trisnilki, because in that moneth they began to milke their kine three times in the day."

Scarcely a poet but praises, or describes, or alludes to the beauties of this month. Darwin sings it as the offspring of the solar beams, and invites it to approach and receive the greetings of the elementa[l] beings:—

Born in yon blaze of orient sky,

Sweet May! thy radiant form unfold;

Unclose thy blue voluptuous eye,

And wave thy shadowy locks of gold.For thee the fragrant zephyrs blow,

For thee descends the sunny shower;

The rills in softer murmers flow,

And brighter blossoms gem the bower.Light Graces dress'd in flowery wreaths,

And tiptoe Joys their hands combine;

And Love his sweet contagion breathes,

And laughing dances round thy shrine.Warm with new life, the glittering throng

On quivering fin and rustling wing

Delighted join their votive songs,

And hail thee, goddess of the spring.

One of Milton's richest fancies is of this month; he says, that Adam, discoursing with Eve—

Smil'd with superior love; as Jupiter

On Juno smiles, when he impregns the clouds

That shed May-flowers.Throughout the wide range of poetic excellence, there is no piece of higher loveliness than his often quoted, yet never tiring

Song on May Morning.

Now the bright morning star, day's harbinger,

Comes dancing from the east, and leads with her

The flowery May, who from her green lap throws

The yellow cowslip, and the pale primrose.

Hail, bounteous May! that dost inspire

Mirth, and youth, and warm desire;

Woods and groves are of thy dressing,

Hill and dale both boast thy blessing!

Thus we salute thee with our early song,

And welcome thee, and wish thee long.With exquisite feeling and exuberant grace he derives Mirth from—

The frolic wind that breathes the spring

Zephyr, with Aurora playing

As he met her once a Maying;and, with beautiful propriety, as regards the season, he makes the scenery

———beds of violets blue,

And fresh blown roses wash'd in dew.The first of his "sonnets" is to the nightingale warbling on a "bloomy spray" at eve, while, as he figures,

"The jolly hours lead on propitious May"

In "a Conversational Poem written in April," by Mr. Coleridge, there is a description of the nightingale's song, so splendid that it may take the place of extracts from other poets who have celebrated the charms of the coming month, wherein this bird's high melody prevails with increasing power:—

All is still,

A balmy night! and tho' the stars be dim,

Yet let us think upon the vernal showers

That gladden the green earth, and we shall find

A pleasure in the dimness of the stars.

And hark? the nightingale begins its song.

He crowds, and hurries, and precipitates

With fast thick warble his delicious notes,

As he were fearful, that an April night

Would be too short for him to utter forth

His love-chaunt, and disburthen his full soul

Of all its music!———I know a grove

Of large extent, hard by a castle huge

Which the great lord inhabits not: and so

This grove is wild with tangling underwood,

And the trim walks are broken up, and grass

thin grass and king-cups grow within the paths.

But never elsewhere in one place I knew

So many nightingales: and far and near

In wood and thicket over the wide grove

They answer and provoke each other's songs—

With skirmish and capricious passagings,

And murmers musical and swift jug jug,

And one low piping sound more sweet than all—

Stirring the air with such a harmony,

That should you close your eyes, you might almost

Forget it was not day! On moonlight bushes,

Whose dewy leafits are but half disclos'd,

You may perchance behold them on the twigs,

Their bright, bright eyes, their eyes both bright and

Glist'ning, while many a glow-worm in the shade

Lights up her love-torch.—————Oft, a moment's space,

What time the moon was lost behind a cloud,

Hath heard a pause of silence: till the moon

Emerging, hath awaken'd earth and sky

With one sensation, and those wakeful birds

Have all burst forth in choral minstrelsy,

As if one quick and sudden gale had swept

An hundred airy harps! And I have watch'd

Many a nightingale perch'd giddily

On blos'my twig, still swinging from the breeze,

And to that motion tune his wanton song,

Like tipsy Joy that reels with tossing head.

St. Philip, and St. James the less. St. Asaph, Bp. of Llan-Elway, A.D. 590. St. Marcon, or Marculfus, A.D. 558. St. Sigismund, king of Burgundy, 6th Cent.St. Philip and St. James.

Philip is supposed to have been the first of Christ's apostles, and to have died at Hierapolis, in Phrygia. James, also surnamed the Just, whose name is borne by the epistle in the New Testament, and who was in great repute among the Jews, was martyred in a tumult in the temple, about the year 62.* [1] St. Philip and St. James are in the church of England Calendar.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Tulip. Tulipa Gesneri.

Dedicated to St. Philip.

Red Campion. Lychnisdioica rubra.

Red Bachelor's Buttons. Lychnis dioicaplena

Dedicated to St. James.May-Day.

Hail! sacred thou to sacred joy,

To mirth and wine, sweet first of May!

To sports, which no grave cares alloy,

The sprightly dance, the festive play!Hail! thou, of ever-circling time

That gracest still the ceaseless flow!

Bright blossom of the season's prime,

Aye, hastening on to winter's snow!When first young Spring his angel face

On earth unveiled, and years of gold,

Gilt with pure ray man's guileless race,

By law's stern terrors uncontrolled[,]Such was the soft and genial breeze

Mild Zephyr breathed on all around;

With grateful glee, to airs like these

Yielded its wealth th' unlaboured ground.So fresh, so fragrant is the gale,

Which o'er the islands of the blest

Sweeps; where nor aches the limbs assail,

Nor age's peevish pains infest.Where thy hushed groves, Elysium, sleep,

Such winds with whispered murmurs blow;

So, where dull Lethe's waters creep,

They heave, scarce heave the cypress-bough.And such, when heaven with penal flame

Shall purge the globe, that golden day

Restoring, o'er man's brightened frame

Haply such gale again shall play.Hail! thou, the fleet year's pride and prime!

Hail! day, which fame shall bid to bloom!

Hail! image of primeval time!

Hail! sample of a world to come!—Buchanan, by Langhorne.

On behalf of this ancient festival, a noble authoress contributes a little "forget me not:"—

The First of May.

Colin met Sylvia on the green,

Once on the charming first of May,

And shepherds ne'er tell false I ween,

Yet 'twas by chance the shepherds say[.]Colin he bow'd and blush'd, then said,

Will you, sweet maid, this first of May

Begin the dance by Colin led,

To make this quite his holiday?Sylvia replied, I ne'er from home

Yet ventur'd, till this first of May;

It is not fit for maids to roam,

And make a shepherd's holiday.It is most fit, replied the youth,

That Sylvia should this first of May

By me be taught that love and truth

Can make of life a holiday.Lady Craven.

"We call," says Mr. Leigh Hunt—"we call upon the admirers of the good and beautiful to help us in 'rescuing nature from obloquy.' All you that are lovers of nature in books, — lovers of music, painting, and poetry, — lovers of sweet sounds, and odours, and colours, and all the eloquent and happy face of the rural world with its eyes of sunshine, —you, that are lovers of your species, of youth, and health, and old age,—of manly strength in the manly, of nymph-like graces in the female,—of air, of exercise, of happy currents in your veins, —of the light in great Nature's picture, —of all the gentle spiriting, the loveliness, the luxury, that now stands under the smile of heaven, silent and solitary as your fellow-creatures have left it, — go forth on May-day, or on the earliest fine May morning, if that be not fine, and pluck your flowers and your green boughs to adorn your rooms with, and to show that you do not live in vain. These April rains (for May has not yet come, according to the old style, which is the proper one of our climate), these April rains are fetching forth the full luxury of the trees and hedges;—by the next sunshine, all 'the green weather,' as a little gladsome child called it, will have come again; the hedges will be so many thick verdant walls, the fields mossy carpets, the trees clothed to their finger-tips with foliage, the birds saturating the woods with song. come forth, come forth."* [2]

This was the great rural festival of our forefathers. Their hearts responded merrily to the cheerfulness of the season. At the dawn of May morning the lads and lasses left their towns and vilages, and repairing to the woodlands by sound of music, they gathered the May, or blossomed branches of the trees, and bound them with wreaths of flowers; then returning to their homes by sunrise, they decorated the lattices and doors with the sweet-smelling spoil of their joyous journey, and spent the remaining hours in sports and pastimes. Spenser's "Shepherd's Calendar" poetically records these customs in a beautiful eclogue:—

Youths folke now flocken in every where

To gather May buskets, and smelling breere;

And home they hasten, the postes to dight,

And all the kirke pillers, ere daylight,

With hawthorne buds, and sweet eglantine,

And girlonds of roses, and soppes in wine.* * * * *

Siker this morrow, no longer ago,

I saw a shole of shepheards outgo

With singing and showting, and jolly cheere;

Before them yode a lustie tabrere,

That to the meynie a hornepipe plaid,

Whereto they dauncen eche one with his maide.

To see these folkes make such jovisaunce,

Made my hart after the pipe to daunce.

Tho' to the greene-wood they speeden them all,

To fetchen home May with their musicall:

And home they bringen, in a royall throne,

Crowned as king; and his queen attone

Was Ladie Flora, on whom did attend

A faire flock of faeries, and a fresh bend

Of lovely nymphs. O, that I were there

To helpen the ladies their May-bush beare!

Forbear censure, gentle readers and kind hearers, for quotations from poets, they have made the day especially their own; they are its annalists. A poet's invitation to his mistress to enjoy the festivity, is historical; if he says to her, "together let us range," he tells her for what; and becomes a grave authority to the grave antiquary. The sweetest of all British bards that sing of our customs, beautifully illustrates the May-day of England:—

Get up, get up for shame, the blooming morne

Upon her wings presents the God unshorne.

See how Aurora throwes her faire

Fresh-quilted colours through the aire;

Get up, sweet slug-a-bed, and see

The dew bespangling herbe and tree.

Each flower has wept, and bow'd toward the east,

Above an houre since, yet you not drest,

Nay! not so much as out of bed;

When all the birds have matteyns seyd,

And sung their thankfull hymnes; 'tis sin,

Nay, profanation to keep in,

When as a thousand virgins on this day,

Spring sooner then the lark, to fetch in May.Rise, and put on your foliage, and be seene

To come forth, like the spring-time, fresh and greene,

And sweet as Flora. Take no care

For jewels for your gowne or haire;

Feare not, the leaves will strew

Gemms in abundance upon you;

Besides, the childhood of the day has kept,

Against you come, some orient pearls unwept.

Come, and receive them while the light

Hangs on the dew-locks of the night:

And Titan on the eastern hill

Retires himselfe, or else stands still

Till you come forth. Wash, dresse, be brief in praying;

Few beads are best, when once we goe a Maying.Come, my Corinna, come; and, comming, marke

How each field turns a street, each street a parke

Made green, and trimm'd with trees; see how

Devotion gives each house a bough,

Or branch; each porch, each doore, ere this,

An arke, a tabernacle is,

Made up of white-thorn neatly interwove;

As if here were those cooler shades of love

Can such delights be in the street,

And open fields, and we not see't?

Come, we'll abroad, and let's obay

The proclamation made for May:

And sin no more, as we have done, by staying

But, my Corinna, come, let's goe a Maying.There's not a budding boy or girle, this day,

But is got up, and gone to bring in May.

A deale of youth, ere this, is come

Back, and with white-thorn laden home.

Some have dispatcht their cakes and creame

Before that we have left to dreame;

And some have wept, and woo'd, and plighted troth,

And chose their priest, ere we can cast off sloth:

Many a green gown has been given;

Many a kisse, both odde and even;

Many a glance, too, has been sent

From out the eye, love's firmament;

Many a jest told of the keye's betraying

This night, and locks pickt; yet w'are not a Maying.Come, let us goe, while we are in our prime

And take the harmlesse follie of the time.

We shall grow old apace and die

Before we know our liberty.

Our life is short, and our dayes run

As fast away as do's the sunne;

And as a vapour, or a drop of raine

Once lost, can ne'r be found againe;

So when or you or I are made

A fable, song, or fleeting shade;

All love, all liking, all delight

Lies drown'd with us in endless night.

Then while time serves, and we are but decaying,

Come, my Corinna, come, let's goe a Maying.Herrick.

A gatherer of notices respecting our pastimes says, "The after-part of May-day is chiefly spent in dancing round a tall Poll, which is called a May Poll; which being placed in a convenient part of the village, stands there, as it were consecrated to the Goddess of Flowers, without the least violation offer'd to it, in the whole circle of the year."* [3] One who was an implacable enemy to popular sports relates the fetching in of "the May" from the woods. "But," says he, "their chiefest jewell they bring from thence is their Maie poole, whiche they bring home with greate veneration, as thus. They have twentie or fourtie yoke of oxen, every oxe havyng a sweete nosegaie of flowers tyed on the tippe of his hornes, and these oxen drawe home this Maie poole, which is covered all over with flowers and hearbes, bounde rounde aboute with stringes, from the top to the bottome, and sometyme painted with variable colours, with two or three hundred men, women, and children followyng it, with greate devotion. And thus beyng reared up, with handkerchiefes and flagges streamyng on the toppe, they strawe the grounde aboute, binde greene boughes about it, sett up Sommer haules, Bowers, and Arbours hard by it. And then fall they to banquet and feast, to leape and daunce aboute it, as the Heathen people did at the dedication of their Idolles, whereof this is a perfect patterne, or rather the thymg itself."* [4]

The May-pole is up,

Now give me the cup;

I'll drink to the garlands around it;

But first unto those

Whose hands did compose

The glory of flowers that crown'd it.Herrick.

Another poet, and therefore no opponent to homely mirth on this festal day, so describes part of its merriment as to make a beautiful picture:—

I have seen the Lady of the May

Set in an arbour (on a holy-day)

Built by the May-pole, where the jocund swaines

Dance with the maidens to the bag-pipes straines,

When envious night commands them to be gone,

Call for the merry youngsters one by one,

And, for their well performance, soon disposes,

To this a garland interwove with roses,

To that a carved hooke, or well-wrought scrip;

Gracing another with her cherry lip;

To one her garter; to another, then,

A handkerchiefe, cast o'er and o'er again;

And none returneth emptie that hath spent

His paines to fill their rural merriment.Browne's Pastorals

A poet, who has not versified, (Mr. Washington Irving,) says, "I shall never forget the delight I felt on first seeing a May-pole. It was on the banks of the Dee, close by the picturesque old bridge that stretches across the river from the quiant little city of Chester. I had already been carried back onto former days by the antiquities of that venerable place; the examination of which is equal to turning over the pages of a black-letter volume, or gazing on the pictures in Froissart. The May-pole on the margin of that poetic stream completed the illusion. My fancy adorned it with wreaths of flowers, and peopled the green bank with all the dancing revelry of May-day. The mere sight of this May-pole gave a glow to my feelings, and spread a charm over the country for the rest of the day; and as I traversed a part of the fair plains of Cheshire, and the beautiful borders of Wales, and looked from among swelling hills down a long green valley, through which 'the Deva wound its wizard stream,' my imagination turned all into a perfect Arcadia.—One can readily imagine what a gay scene it must have been in jolly old London, when the doors were decorated with flowering branches, when every hat was decked with hawthorn; and Robin Hood, friar Tuck, Maid Marian, the morris-dancers, and all the other fantastic masks and revellers were performing their antics about the May-pole in every part of the city. On this occasion we are told Robin Hood presided as Lord of the May:—

"With coat of Lincoln green, and mantle too,

And horn of ivory mouth, and buckle bright,

And arrows winged with peacock-feathers light,

And trusty bow well gathered of the yew;"whilst near him, crowned as Lady of the May, maid Marian,

"With eyes of blue,

Shining through dusk hair, like the stars of night,

And habited in pretty forest plight—

His green-wood beauty sits, young as the dew:"and there, too, in a subsequent stage of the pageant, were

"The archer-men in green, with belt and bow,

Feasting on pheasant, river-fowl, and swan,

With Robin at their head, and Marian."I value every custom that tends to infuse poetical feeling into the common people, and to sweeten and soften the rudeness of rustic manners, without destroying their simplicity. Indeed it is to the decline of this happy simplicity that the decline of this custom may be traced; and the rural dance on the green, and the homely May-day pageant, have gradually disappeared, in proportion as the peasantry have become expensive and artificial in their pleasures, and too knowing for simple enjoyment. Some attempts, indeed, have been made of late years, by men of both taste and learning, to rally back the popular feeling to these standards of primitive simplicity; but the time has gone by, the feeling has become chilled by habits of gain and traffic; the country apes the manners and amusements of the town, and little is heard of May-day at present, except from the lamentations of authors, who sigh after it from among the brick walls of the city."

There will be opportunity in the course of this work to dilate somewhat concerning the May-pole and the characters in the May-games, and therefore little will be adduced at present as to the origin of pastimes, which royalty itself delighted in, and corporations patronized. For example of these honours to the festal day, an honest gatherer of older chronicles shall relate in his own words, so much as he acquaints us with:—

" In the moneth of May, namely on May day in the morning, every man, except impediment, would walke into the sweet meddowes and green woods, there to rejoyce their spirits with the beauty and savour of sweet flowers, and with the harmonie of birds, praising God in their kinde. And for example hereof, Edward Hall hath noted, that king Henry the eighth, as in the third of his reigne, and divers other yeeres, so namely in the seventh of his reigne, on May day in the morning, with queen Katharine for his wife, accompanied with many lords and ladies, rode a Maying from Greenwich to the high ground of Shooters-hill: where as they passed by the way, they espyed a company of tall yeomen, clothed all in greene, with greene hoods, and with bowes and arrowes, to the number of 200. One, being their chieftaine, was called Robin Hood, who required the king and all his company to stay and see his men shoot: whereunto the king granting, Robin Hood whistled, and all the 200 archers shot off, loosing all at once; and when he whistled againe, they likewise shot againe" their arrows whistled by craft of the head, so that the noise was strange and loud, which greatly delighted the king, queene, and their company.

"Moreover, this Robin Hood desired the king and queene, with their retinue, to enter the greene wood, where, in arbours made of boughes, and deckt with flowers, they were set and served plentifully with venison and wine, by Robin Hood and his meyny, to their great contentment, and had other pageants and pastimes; as yee may read in my said author.

"I find also, that in the month of May, the citizens of London (of all estates) lightly in every parish, or sometimes two or three parishes joyning together, had their severall Mayings, and did fetch in May-poles, with divers warlike shewes, with good archers, morice-dancers, and other devises for pastime all the day long; and towards the evening, they had stage-plaies, and bonefires in the streets.

"Of these Mayings, we read in the reign of Henry the sixth, that the aldermen and sheriffes of London, being on May day at the bishop of Londons wood in the parish of Stebunheath, and having there a worshipfull dinner for themselves and other commers, Lydgate the poet, that was a monk of Bury, sent to them by a pursivant a joyfull commendation of that season, containing sixteene staves in meeter royall, beginning thus:—

"Mighty Flora, goddesse of fresh flowers,

which clothed hath the soyle in lusty green,

Made buds to spring, with her sweet showers,

by influence of the sunne shine,

To doe pleasance of intent full cleane,

unto the states which now sit here,

Hath Ver downe sent her own daughter deare,"Making the vertue, that dured in the root,

Called the vertue, the vertue vegetable,

for to transcend, most wholesome and most soote,

Into the top, this season so agreeable:

the bawmy liquor is so commendable,

That it rejoyceth with his fresh moisture,

man, beast, and fowle, and every creature," &c.Thus far hath our London historian conceived it good for his fellow citizens to know.

Of the manner wherein a May game was anciently set forth, he who above all writers contemporary with him could best devise it has "drawn out the platform," and exhibited the pageant, as performed by the household servants and dependants of a baronial mansion in the fifteenth century. This is the scene:— "In the front of the pavilion, a large square was staked out, and fenced with ropes, to prevent the crowd from pressing upon the performers, and interrupting the diversion; there were also two bars at the bottom of the inclosure, through which the actors might pass and repass, as occasion required.—Six young men first entered the square, clothed in jerkins of leather, with axes upon their shoulders like woodmen, and their heads bound with large garlands of ivy-leaves, intertwined with sprigs of hawthorn. Then followed six young maidens of the village, dressed in blue kirtles, with garlands of primroses on their heads, leading a fine sleek cow decorated with ribbons of various colours, interspersed with flowers; and the horns of the animal were tipped with gold. These were succeeded by six foresters, equipped in green tunics, with hoods and hosen of the same colour; each of them carried a bugle-horn attached to a baldrick of silk, which he sounded as he passed the barrier. After them came Peter Lanaret, the baron's chief falconer, who personified Robin Hood; he was attired in a bright grass-green tunic, fringed with gold; his hood and his hosen were parti-coloured, blue and white; he had a large garland of rosebuds on his head, a bow bent in his hand, a sheaf of arrows at his girdle, and a bugle-horn depending from a baldrick of light blue tarantine, embroidered with silver; he had also a sword and a dagger, the hilts of both being richly embossed with gold.— Fabian, a page, as Little John, walked at his right hand; and Cecil Cellerman the butler, as Will Stukely, at his left. These, with ten others of the jolly outlaw's attendants who followed, were habited in green garments, bearing their bows bent in their hands, and their arrows in their girdles. Then came two maidens, in orange-coloured kirtles with white courtpies, strewing flowers, followed immediately by the Maid Marian, elegantly habited in a watchet-coloured tunic reaching to the ground; over which she wore a white linen rochet with loose sleeves, fringed with silver, and very neatly plaited; her girdle was of silver baudekin, fastened with a double bow on the left side; her long flaxen hair was divided into many ringlets, and flowed upon her shoulders; the top part of her head was covered with a net-work cawl of gold, upon which was placed a garland of silver, ornamented with blue violets. She was supported by two bride-maidens, in sky-coloured rochets girt with crimson girdles, wearing garlands upon their heads of blue and white violets. After them came four other females in green courtpies, and garlands of violets and cowslips. Then Sampson the smith, as Friar Tuck, carrying a huge quarter-staff on his shoulder; and Morris the mole-taker, who represented Much the miller's son, having a long pole with an inflated bladder attached to one end. And after them the May-pole, drawn by eight fine oxen, decorated with scarfs, ribbons, and flowers of divers colours; and the tips of their horns were embellished with gold. The rear was closed by the hobby-horse and the dragon. —When the May-pole was drawn into the square, the foresters sounded their horns, and the populace expressed their pleasure by shouting incessantly until it reached the place assigned for its elevation:— and during the time the ground was preparing for its reception, the barriers of the bottom of the inclosure were opened for the villagers to approach, and adorn it with ribbons, garlands, and flowers, as their inclination prompted them. — The pole being sufficiently onerated with finery, the square was cleared from such as had no part to perform in the pageant; and then it was elevated amidst the reiterated acclamations of the spectators. The woodmen and the milk-maidens danced around it according to the rustic fashion; the measure was played by Peretto Cheveritte, the baron's chief minstrel, on the bagpipes accompanied with the pipe and tabour, performed by one of his associates. When the dance was finished, Gregory the jester, who undertook to play the hobby-horse, came forward with his appropriate equipment, and, frisking up and down the square without restriction, imitated the galloping, curvetting, ambling, trotting, and other paces of a horse, to the inifinite satisfaction of the lower classes of the spectators. He was followed by Peter Parker, the baron's ranger, who personated a dragon, hissing, yelling, and shaking his wings with wonderful ingenuity; and to complete the mirth, Morris, in the character of Much, having small bells attached to his knees and elbows, capered here and there between the two monsters in the form of a dance; and as often as he came near to the sides of the inclosure, he cast slily a handful of meal into the faces of the gaping rustics, or rapped them about their heads with the bladder tied at the end of his pole. In the mean time, Sampson, representing Friar Tuck, walked with much gravity around the square, and occasionally let fall his heavy staff upon the toes of such of the crowd as he thought were approaching more forward than they ought to do; and if the sufferers cried out from the sense of pain, he addressed them in a solemn tone of voice, advising them to count their beads, say a paternoster or two, and to beware of purgatory. These vagaries were highly palatable to the populace, who announced their delight by repeated plaudits and loud bursts of laughter; for this reason they were continued for a considerable length of time: but Gregory, beginning at last to faulter in his paces, ordered the dragon to fall back: the well-nurtured beast, being out of breath, readily obeyed, and their two companions followed their example; which concluded this part of the pastime. — Then the archers set up a target at the lower part of the green, and made trial of their skill in a regular succession. Robin Hood and Will Stukely excelled their comrades; and both of them lodged an arrow in the centre circle of gold, so near to each other that the difference could not readily be decided, which occasioned them to shoot again; when Robin struck the gold a second time, and Stukely's arrow was affixed upon the edge of it. Robin was therefore adjudged the conqueror; and the prize of honour, a garland of laurel embellished with variegated ribbons, was put upon his head; and to Stukely was given a garland of ivy, because he was the second best performer in that contest. — The pageant was finished with the archery; and the procession began to move away to make room for the villagers, who afterwards assembled in the square, and amused themselves by dancing round the May-pole in promiscuous companies, according to the antient custom." [5] It is scarcely possible to give a better general idea of the regular May-game, than as it has been here represented.

Of the English May-pole this may be observed. An author before cited says, that "at the north-west corner of Aldgate ward in Leadenhall-street, standeth the fair and beautiful parish church of St. Andrew the apostle, with an addition, to be known from other churches of that name, of the knape, or undershaft, and so called St. Andrew Undershaft because that of old time, every year (on May-day in the morning,) it was used, that a high or long shaft, or May-pole, was set up there, in the midst of the street, before the south door of the said church, which shaft or pole, when it was set on end, and fixed in the ground, was higher than the church steeple. Jeffrey Chaucer, writing of a vain boaster, hath these words, meaning of the said shaft:—

"Right well aloft, and high ye bear your head,

* * * * *

As ye would bear the great shaft of Corn-hill.This shaft was not raised any time since evil May day, (so called of an insurrection being made by prentices, and other young persons against aliens, in the year 1517,) but the said shaft was laid along over the doors, and under the pentices of one rowe of houses, and Alley-gate, called of the shaft, Shaft-alley, (being of the possessions of Rochester-bridge,) in the ward of Lime-street.— It was there, I say, hanged on iron hooks many years, till the third of king Edward the sixth, (1552), that one sir Stephen, curate of St. Katherine Christ's church, preaching at Paul's Cross, said there, that this shaft was made an idoll, by naming the church of St. Andrew with the addition of Undershaft; he perswaded, therefore, that the names of churches might be altered.—This sermon at Paul's Cross took such effect, that in the afternoon of that present Sunday, the neighbors and tenants to the said bridge, over whose doors the said shaft had lain, after they had dined (to make themselves strong,) gathered more help, and, with great labor, raising the shaft from the hooks, (whereon it had rested two-and-thirty years,) they sawed it in pieces, every man taking for his share so much as had lain over his door and stall, the length of his house; and they of the alley, divided amongst them, so much as had lain over their alley-gate. Thus was his idoll (as he termed it,) mangled, and after burned."* [6]

It was a great object with some of the more rigid among our early reformers, to suppress amusements, especially May-poles; and these "idols" of the people were got down as zeal grew fierce, and got up as it grew cool, till, after various ups and downs, the favourites of the populace were, by the parliament, on the 6th of April, 1644, thus provided against: "The lords and commons do further order and ordain, that all and singular May-poles, that are or shall be erected, shall be taken down, and removed by the constables, bossholders, tithing-men, petty constables, and churchwardens of the parishes, where the same be, and that no May-pole be hereafter set up, erected, or suffered to be set up within this kingdom of England, or dominion of Wales; the said officers to be fined five shillings weekly till the said May-pole be taken down."

Accordingly down went all the May-poles that were left. A famous one in the Strand, which had ten years before been sung in lofty metre, appears to have previously fallen. The poet says,—

Fairly we marched on, till our approach

Within the spacious passage of the Strand,

Objected to our sight a summer broach,

Y cleap'd a May Pole, which in all our land,

No city, towne, nor streete, can parralell,

Nor can the lofty spire of Clarken-well,

Although we have the advantage of a rocke,

Pearch up more high his turning weather-cock.Stay, quoth my Muse, and here behold a signe

Of harmelesse mirth and honest neighbourhood,

Where all the parish did in one combine

To mount the rod of peace, and none withstood:

When no capritious constables disturb them,

Nor justice of the peace did seek to curb them,

Nor peevish puritan, in rayling sort,

Nor over-wise church-warden, spoyl'd the sport.Happy the age, and harmlesse were the dayes,

(For then true love and amity was found,)

When every village did a May Pole raise,

And Whitson-ales and MAY-GAMES did abound:

And all the lusty yonkers, in a rout,

With merry lasses daunc'd the rod about,

Then Friendship to their banquets bid the guests,

And poore men far'd the better for their feasts.The lords of castles, mannors, townes, and towers,

Rejoic'd when they beheld the farmer's flourish,

And would come downe unto the summer-bowers

To see the country-gallants dance the Morrice.

* * * * * *But since the SUMMER POLES were overthrown,

And all good sports and merriments decay'd,

How times and men are chang'd, so well is knowne,

It were but labour lost if more were said.

* * * * * *But I doe hope once more the day will come,

That you shall mount and pearch your cocks as high

As ere you did, and that the pipe and drum

Shall bid defiance to your enemy;

And that all fidlers, which in corners lurke,

And have been almost starv'd for want of worke,

Shall draw their crowds, and, at your exaltation,

Play many a fit of merry recreation.*[7]The restoration of Charles II. was the signal for the restoration of May-poles. On the very first May-day afterwards, in 1661, the May-pole in the Strand was reared with great ceremony and rejoicing, a curious account of which, from a rare tract, is at the reader's service. "Let me declare to you," says the triumphant narrator, "the manner in general of that stately cedar erected in the strand 134 foot high, commonly called the May-Pole, upon the cost of the parishioners there adjacent, and the gracious consent of his sacred Majesty with the illustrious Prince The Duke of York. This Tree was a most choice and remarkable piece; 'twas made below Bridge, and brought in two parts up to Scotland Yard near the King's Palace, and from thence it was conveyed April 14th to the Strand to be erected. It was brought with a streamer flourishing before it, Drums beating all the way and other sorts of musick; it was supposed to be so long, that Landsmen (as Carpenters) could not possibly raise it; (Prince James the Duke of York, Lord High Admiral of England, commanded twelve seamen off a boord to come and officiate the business, whereupon they came and brought their cables, Pullies, and other tacklins, with six great anchors) after this was brought three Crowns, bore by three men bare-headed and a streamer displaying all the way before them, Drums beating and other musick playing; numerous multitudes of people thronging the streets, with great shouts and acclamations all day long. The May pole then being joyned together, and hoopt about with bands of iron, the crown and cane with the Kings Arms richly gilded, was placed on the head of it, a large top like a Balcony was about the middle of it. This being done, the trumpets did sound, and in four hours space it was advanced upright, after which being established fast in the ground six drums did beat, and the trumpets did sound; again great shouts and acclamations the people give, that it did ring throughout all the strand. After that came a Morice Dance finely deckt, with purple scarfs, in their half-shirts, with a Tabor and Pipe, the ancient Musick, and danced round about the Maypole, and after that danced the rounds of their liberty. Upon the top of this famous standard is likewise set up a royal purple streamer, about the middle of it is placed four Crowns more, with the King's Arms likewise, there is also a garland set upon it of various colours of delicate rich favours, under which is to be placed three great Lanthorns, to remain for three honours; that is, one for Prince James Duke of York, Ld High Admiral of England; the other for the Vice Admiral; and the third for the rear Admiral; these are to give light in dark nights and to continue so as long as the Pole stands which will be a perpetual honour for seamen. It is placed as near hand as they could guess, in the very same pit where the former stood, but far more glorious, bigger and higher, than ever any one that stood before it; and the seamen themselves do confess that it could not be built higher nor is there not such a one in Europe beside, which highly doth please his Majesty, and the illustrious Prince Duke of York; little children did much rejoice, and antient people did clap their hands, saying, golden days began to appear. I question not but 'twill ring like melodious musick throughout every county in Englend [sic], when they read this story being exactly pen'd; let this satisfie for the glories of London that other loyal subjects may read what we here do see."* [8]

A processional engraving, by Vertue, among the prints of the Antiquarian Society, represents this May-pole, as a door or two westward beyond

"Where Catharine-street descends into the Strand;"

and as far as recollection of the print serves, it was erected opposite to the site of sir Walter Stirling and Co's. present banking-house. In a compilation respecting "London and Middlesex," it is stated that this May-pole having decayed, was obtained of the parish by sir Isaac Newton, in 1717, and carried through the city to Wanstead, in Essex; and by license of sir Richard Child, lord Castlemain, reared in the park by the rev. Mr. Pound, rector of that parish, for the purpose of supporting the largest telescope at that period in the world, given by Mons. Hugon, a French member of the Royal Society, as a present; the telescope was one hundred and twenty-five feet long. This May-pole on public occasions was adorned with streamers, flags, garlands of flowers and other ornaments.

It was near the May-pole in the Strand that, in 1677, Mr. Robert Perceval was found dead with a deep wound under his left breast, and his sword drawn and bloody, lying by him. He was nineteen years of age, had fought as many duels as he had lived years, and with uncommon talents was an excessive libertine. He was second son to the right hon. sir Robert Perceval, bart. Some singular particulars are related of him in the "History of the House of Yvery." A stranger's hat with a bunch of ribbons in it was lying near his body when it was discovered, and there exists no doubt of his having been killed by some person who, notwithstanding royal proclamations and great inquiries, was never discovered. The once celebrated Beau Fielding was suspected of the crime. He was buried under the chapel of Lincoln's-inn. His elder brother, sir Philip Perceval, intent on discovering the murderers, violently attacked a gentleman in Dublin, whom he declared he had never seen before; he could only account for his rage by saying he was possessed with a belief that he was one of those who had killed his brother; they were soon parted, and the gentleman was seen no more.

The last poet who seems to have mentioned it was Pope; he says of an assemblage of persons that,—

Amidst the area wide they took their stand,

Where the tall May-pole once o'er-look'd the Strand.

A native of Penzance, in Cornwall, relates to the editor of the Every-Day Book, that it is an annual custom there, on May-eve, for a number of young men and women to assemble at a public-house, and sit up till the clock strikes twelve, when they go round the town with violins, drums, and other instruments, and by sound of music call upon others who had previously settled to join them. As soon as the party is formed, they proceed to different farmhouses, within four or five miles of the neighbourhood, where they are expected as regularly as May morning comes; and they there partake of a beverage called junket, made of raw milk and rennet, or running, as it is there called, sweetened with sugar, and a little cream added. After this, they take tea, and "heavy country cake," composed of flour, cream, sugar, and currants; next, rum and milk, and then a dance. After thus regaling, they gather the May. While some are breaking down the boughs, others sit and make the "May music." This is done by cutting a circle through the bark at a certain distance from the bottom of the May branches; then, by gently and regularly tapping the bark all round, from the cut circle to the end, the bark becomes loosened, and slips away whole from the wood; and a hole being cut in the pipe, it is easily formed to emit a sound when blown through, and becomes a whistle. The gathering and the "May music" being finished, they then "bring home the May," by five or six o'clock in the morning, with the band playing, and their whistles blowing. After dancing throughout the town, they go to their respective employments. Although May-day should fall on a Sunday, they observe the same practice in all respects, with the omission of dancing in the town.

On the first Sunday after May-day, it is a custom with families at Penzance to visit Rose-hill, Poltier, and other adjacent villages, by way of recreation. These pleasure-parties usually consist of two or three families together. They carry flour and other materials with them to make the "heavy cake," just described, at the pleasant farm-dairies, which are always open for their reception. Nor do they forget to take tea, sugar, rum, and other comfortable things for their refreshment, which, by paying a trifle for baking, and for the niceties awaiting their consumption, contents the farmers for the house-room and pleasure they afford their welcome visitants. Here the young ones find delicious "junkets," with "sour milk," or curd cut in diamonds, which is eaten with sugar and cream. New made cake, refreshing tea, and exhilarating punch, satisfy the stomach, cheer the spirits, and assist the walk home in the evening. These pleasure-takings are never made before May-day; but the first Sunday that succeeds it, and the leisure of every other afternoon, is open to the frugal enjoyment; and among neighbourly families and kind friends, the enjoyment is frequent.

To the Editor of the Every-Day Book.

Sir,

There still exists among the labouring classes in Wales the custom of May-dancing, wherein they exhibit their persons to the best advantage, and distinguish their agility before the fair maidens of their own rank.About a fortnight previous to the day, the interesting question among the lads and lasses is, "Who will turn out to dance in the summer this year?" From that time the names of the gay performers are buzzed in the village, and rumour "with her hundred tongues" proclaims them throughout the surrounding neighbourhood. Nor is it asked with less interest, "Who will carry the garland?" and "Who will be the Cadi?" Of the peculiar offices of these two distinguished personages you shall hear presently.About nine days or a week previous to the festival, a collection is made of the gayest ribbons that can be procured. Each lad resorts to his favoured lass, who gives him the best she possesses, and uses her utmost interest with her friends or her mistress to obtain a loan of whatever may be requisite to supply the deficiency. Her next care is to decorate a new white shirt of fine linen. This is a principal part of her lover's dress. The bows and puffs of ribbon are disposed according to the peculiar taste of each fair girl who is rendered happy by the pleasing task; and thus the shirts of the dancers, from the various fancies of the adorners, form a diversified and lively appearance.During this time the chosen garland-bearer is also busily employed. Accompanied by one from among the intended dancers, who is best known among the farmers for decency of conduct, and consequent responsibility, they go from house to house, throughout their parish, begging the loan of watches, silver spoons, or whatever other utensils of this metal are likely to make a brilliant display; and those who are satisfied with the parties, and have a regard for the celebration of this ancient day, comply with their solicitation.When May-day morn arrives, the group of dancers assemble at their rendezvous—the village tavern. From thence (when permission can be obtained from the clergyman of the parish,) the rustic procession sets forth, accompanied by the ringing of bells.The arrangement and march are settled by the Cadi, who is always the most active person in the company; and is, by virtue of his important office, the chief marshal, orator, buffoon, and money collector. He is always arrayed in comic attire, generally in a partial dress of both sexes: a coat and waistcoat being used for the upper part of the body, and for the lower petticoats, somewhat resembling Moll Flagon, in the "Lord of the Manor." His countenance is also particularly distinguished by a hideous mask, or is blackened entirely over; and then the lips, cheeks, and orbits of the eyes are sometimes painted red. The number of the rest of the party, including the garland-bearer, is generally thirteen, and with the exception of the varied taste in the decoration of their shirts with ribbons, their costume is similar. It consists of clothing entirely new from the hat to the shoes, which are made neat, and of a light texture, for dancing. The white decorated shirts, plaited in the neatest manner, are worn over the rest of their clothing; the remainder of the dress is black velveteen breeches, with knee-ties depending half-way down to the ancles, in contrast with yarn hose of a light grey. The ornaments of the hats are large rosettes of varied colours, with streamers depending from them; wreaths of ribbon encircle the crown, and each of the dancers carries in his right hand a white pocket handkerchief.The garland consists of a long staff or pole, to which is affixed a triangular or square frame, covered with strong white linen, on which the silver ornaments are firmly fixed, and displayed with the most studious taste. Silver spoons and smaller forms are placed in the shape of stars, squares, and circles. Between these are rows of watches; and at the top of the frame, opposite the pole in its centre, their whole collection is crowned with the largest and most costly of the ornaments; generally a large silver cup or tankard. This garland, when completed, on the eve of May-day, is left for the night at that farmhouse from whence the dancers have received the most liberal loan of silver and plate for its decoration, or with that farmer who is distinguished in his neighbourhood as a good master, and liberal to the poor. Its deposit is a token of respect, and it is called for early on the following morning.The whole party being assembled, they march in single file, but more generally in pairs, headed by the Cadi. After him follows the garland-bearer, and then the fiddler, while the bells of the village merrily ring the signal of their departure. As the procession moves slowly along, the Cadi varies his station, hovers about his party, brandishes a ladle, and assails every passenger with comic eloquence and ludicrous persecution, for a customary and expected donation.When they arrive at a farmhouse, they take up their ground on the best station for dancing. The garland-bearer takes his stand; the violin strikes up an old national tune uniformly used on that occasion, and the dancers move forward in a regular quick-step to the tune, in the order of procession; and at each turn of the tune throw up their white handkerchiefs with a shout, and the whole facing quickly about, retrace their steps, repeating the same manœuvre until the tune is once played. The music and dancing then vary into a reel, which is succeeded by another dance, to the old tune of "Cheshire Round."During the whole of this time, the buffoonery of the Cadi is exhibited without intermission. He assails the inmates of the house for money, and when this is obtained he bows or curtsies his thanks, and the procession moves off to the next farmhouse. They do not confine the ramble of the day to their own parish, but go from one to another, and to any country town in the vicinity.When they return to their resident village in the evening, the bells ringing merrily announce their arrival. The money collected during the day's excursion is appropriated to defray whatever expenses may have been incurred in the necessary preparations, and the remainder is spent in jovial festivity.This ancient custom, like many others among the ancient Britons, is annually growing into disuse. The decline of sports and pastimes is in every age a subject of regret. For in a civil point of view, they denote the general prosperity, natural energy, and happiness of the people, consistent with morality,—and combined with that spirit of true religion, which unlike the howling of the dismal hyæna or ravening wolf, is as a lamb sportive and innocent, and as a lion magnanimous and bold!I am, Sir,

Yours sincerely,

H. T. B.April 14, 1825.

MAY-DAY AT HITCHIN, IN HERTFORDSHIRE.

For the Every-Day Book.

EXTRACT from a letter dated Hitchin, May 1st, 1823.

On this day a curious custom is observed here, of which I will give you a brief account.Soon after three o'clock in the morning a large party of the town-people, and neighbouring labourers, parade the town, singing the "Mayer's Song." They carry in their hands large branches of May, and they affix a branch either upon, or at the side of, the doors of nearly every respectable house in the town; where there are knockers, they place these branches within the handles; that which was put into our knocker was so large that the servant could not open the door till the gardener came and took it out. The larger the branch is, that is placed at the door, the more honourable to the house, or rather to the servants of the house. If, in the course of the year, a servant has given offence to any of the Mayers, then, instead of a branch of May, a branch of elder, with a bunch of nettles, is affixed to her door: this is considered a great disgrace, and the unfortunate subject of it is exposed to the jeers of her rivals. On May morning, therefore, the girls look with some anxiety for their May-branch, and rise very early to ascertain their good or ill fortune. The houses are all thus decorated by four o'clock in the morning. Throughout the day parties of these Mayers are seen dancing and frolicking in various parts of the town. The group that I saw to-day, which remained in Bancroft for more than an hour, was composed as follows. First came two men with their faces blacked, one of them with a birch broom in his hand, and a large artificial hump on his back; the other dressed as a woman, all in rags and tatters, with a large straw bonnet on, and carrying a ladle: these are called "mad Moll and her husband:" Next came two men, one most fantastically dressed with ribbons, and a great variety of gaudy coloured silk handkerchiefs tied round his arms from the shoulders to the wrists, and down his thighs and legs to the ancles; he carried a drawn sword in his hand; leaning upon his arm was a youth dressed as a fine lady, in white muslin, and profusely bedecked from top to toe with gay ribbons: these, I understood, were called the "Lord and Lady" of the company; after these followed six or seven couples more, attired much in the same style as the lord and lady, only the men were without swords. When this group received a satisfactory contribution at any house, the music struck up from a violin, clarionet, and fife, accompanied by the long drum, and they began the merry dance, and very well they danced, I assure you; the men-women looked and footed it so much like real women, that I stood in great doubt as to which sex they belonged to, till Mrs. J.—— assured me that women were not permitted to mingle in these sports. While the dancers were merrily footing it, the principal amusement to the populace was caused by the grimaces and clownish tricks of mad Moll and her husband. When the circle of spectators became so contracted as to interrupt the dancers, then mad Moll's husband went to work with his broom, and swept the road-dust, all round the circle, into the faces of the crowd, and when any pretended affronts were offered (and many were offered) to his wife, he pursued the offenders, broom in hand; if he could not overtake them, whether they were males or females, he flung his broom at them. These flights and pursuits caused an abundance of merriment.I saw another company of Mayers in Sun-street, and, as far as I could judge from where I stood, it appeared to be of exactly the same description as that above-mentioned, but I did not venture very near them, for I perceived mad Moll's husband exercising his broom so briskly upon the flying crowd, that I kept at a respectful distance.

May-day at Hitchin, in Hertfordshire.

The "Mayer's Song" is a composition, or rather a medley, of great antiquity, and I was therefore very desirous to procure a copy of it; in accomplishing this, however, I experienced more difficulty than I had anticipated; but at length succeeded in obtaining it from one of the Mayers. The following is a literal transcript of it:

The Mayer's Song.

Remember us poor Mayers all,

And thus do we begin

To lead our lives in righteousness,

Or else we die in sin.We have been rambling all this night,

And almost all this day,

And now returned back again

We have brought you a branch of May.A branch of May we have brought you,

And at your door it stands,

It is but a sprout,

But it's well budded out

By the work of our Lord's hands.The hedges and trees they are so green,

As green as any leek,

Our heavenly Father He watered them

With his heavenly dew so sweet.The heavenly gates are open wide,

Our paths are beaten plain,

And if a man be not too far gone,

He may return again.The life of man is but a span,

It flourishes like a flower,

We are here to-day, and gone to-morrow,

And we are dead in an hour.The moon shines bright, and the stars give a light,

A little before it is day,

So God bless you all, both great and small,

And send you a joyful May.

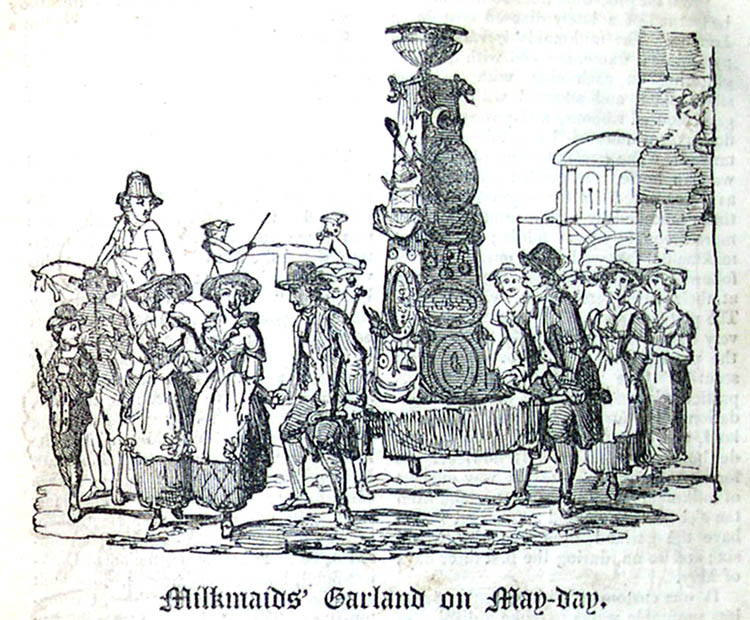

Milkmaids' Garland on May-day.

In London, thirty years ago,

When pretty milkmaids went about,

It was a goodly sight to see

Their May-day Pageant all drawn out:—Themselves in comely colours drest,

Their shining garland in the middle,

A pipe and tabor on before,

Or else the foot-inspiring fiddle.They stopt at houses, where it was

Their custom to cry "milk below!"

And, while the music play'd, with smiles

Join'd hands, and pointed toe to toe.Thus they tripp'd on, till—from the door

The hop'd for annual present sent—

A signal came, to curtsy low,

And at that door cease merriment[.]Such scenes, and sounds, once blest my eyes,

And charm'd my ears— but all have vanish'd!

On May-day, now, no garlands go,

For milk-maids, and their dance, are banish'd.My recollections of these sights

"Annihilate both time and space;"

I'm boy enough to wish them back,

And think their absence—out of place.May 4, 1825.

From the preceding lines somewhat may be learned of a lately disused custom in London. The milkmaids' garland was a pyramidical frame, covered with damask, glittering on each side with polished silver plate, and adorned with knots of gay-coloured ribbons, and posies of fresh flowers, surmounted by a silver urn, or tankard. The garland being placed on a wooden horse, was carried by two men, as represented in the engraving, sometimes preceded by a pipe and tabor, but more frequently by a fiddle; the gayest milkmaids followed the music, others followed the garland, and they stopped at their customers' doors, and danced. The plate, in some of these garlands, was very costly. It was usually borrowed of the pawnbrokers, for the occasion, upon security. One person in that trade was particularly resorted to for this accommodation. He furnished out the entire garland, and let it at so much per hour, under bond from responsible housekeepers for its safe return. In this way one set of milkmaids would hire the garland from ten o'clock till one, and another set would have the garland from one o'clock till six; and so on, during the first three days of May.

It was customary with milk-people of less profitable walks to make a display of another kind, less gaudy in appearance, but better bespeaking their occupation, and more appropriate to the festival. This was an exhibition of themselves, in their best apparel, and of the useful animal which produced the fluid they retailed. One of these is thus described to the editor of the Every-Day Book, by an intelligent eye-witness, and admirer of the pleasant sight. A beautiful country girl "drest all in her best," and more gaily attired than on any other day, with floral ornaments in her neat little hat, and on her bosom, led her cow, by a rope depending from its horns, garlanded with flowers and knots of ribbons; the horns, neck, and head of the cow were decorated in like manner: a fine net, like those upon ladies' palfreys, tastefully stuck with flowers, covered Bess's back, and even her tail was ornamented, with products of the spring, and silken knots. The proprietress of the cow, a neat, brisk, little, matronly body, followed on one side, in holiday-array, with a sprig in her country bonnet, a blooming posy in her handkerchief, and ribbons on her stomacher. This scene was in Westminster, near the old abbey. Ah! those were the days.

The milkmaids' earlier plate-garland was a pyramid of piled utensils, carried on a stout damsel's head, under which she danced to the violin.

MAY-FAIR.

The great May-fair was formerly held near Piccadilly. An antiquary, (shudder not, good reader, at the chilling name—he was a kind soul,) Mr. Carter, describes this place in an interesting communication, dated the 6th of March, 1816, to his valued friend, the venerable "Sylvanus Urban." "Fifty years have passed away since this place of amusement was at its height of attraction: the spot where the fair was held still retains the name of May-fair, and exists in much the same state as at the above period: for instance, Shepherd's market, and houses surrounding it on the north and east sides, with White Horse-street, Shepherd's-court, Sun-court, Market-court. Westwards an open space extending to Tyburn (now Park) lane, since built upon, in chapel-street, Shepherd's-street, Market-street, Hertford-street, &c. Southwards, the noted Ducking-pond, house, and gardens, since built upon, in a large Riding-school, Carrington-street, (the noted Kitty Fisher lived in this street,) &c. The market-house consisted of two stories; first story, a long and cross aisle, for butcher's shops, externally, other shops connected with culinary purposes; second story, used as a theatre at fair-time, for dramatic performances. My recollection serves to raise before me the representation of the 'Revenge,' in which the only object left on remembrance is the 'black man,' Zanga. Below, the butchers gave place to toy-men and gingerbread-bakers. At present, the upper story is unfloored, the lower ditto nearly deserted by the butchers, and their shops occupied by needy peddling dealers in small wares; in truth, a most deplorable contrast to what once was such a point of allurement. In the areas encompassing the market-building were booths for jugglers, prize-fighters, both at cudgels and back-sword, boxing-matches, and wild beasts. The sports not under cover were mountebanks, fire-eaters, ass-racing, sausage-tables, dice-tables, up-and-downs, merry-go-rounds, bull-baiting, grinning for a hat, running for a shift, hasty-pudding eaters, eel-divers, and an infinite variety of other similar pastimes. Among the extraordinary and wonderful delights of the happy spot, take the following items, which still hold a place within my mind, though I cannot affirm they all occurred at one precise season. The account may be relied on, as I was born, and passed my youthful days in the vicinity, in Piccadilly, (Carter's Statuary,) two doors from the south end of White Horse-street, since rebuilt (occupied at present by lady Pulteney).— Before a large commodious house, with a good disposure of walks, arbours, and alcoves, was an area, with an extensive bason of water, otherwise 'Ducking-pond,' for the recreation of lovers of the polite and humane sport. Persons who came with their dogs paid a trifling fee for admission, and were considered the chief patrons and supporters of the pond; others, who visited the place as mere spectators, paid a double fee. A duck was put into the pond by the master of the hunt; the several dogs were then let loose, to seize the bird. For a long time they made the attempt in vain; for, when they came near the devoted victim, she dived under water, and eluded their remorseless fangs. Herein consisted the extreme felicity of the interesting scene. At length, some dog more expert than the rest, caught the feathered prize, and bore it away, amidst the loudest acclamations, to its most fortunate and envied master. This diversion was held in such high repute about the reign of Charles II., that he, and many of his prime nobility, did not disdain to be present, and partake, with their dogs, of the elegant entertainment. In Mrs. Behn's play of 'Sir Patient Fancy,' (written at the above period,) a sir Credulous Easy talks about a cobbler, his dog-tutor, and his expectation of soon becoming 'the duke of Ducking-pond.' — A 'Mountebanks' Stage' was erected opposite the Three Jolly Butchers' public-house, (on the east side of the market area, now the King's Arms.) Here Woodward, the inimitable comedian and harlequin, made his first appearance as merry-andrew; from these humble boards he soon after found his way to Covent-garden theatre. — then there was 'Beheading of Puppets.' In a coal-shed attached to a grocer's shop, (then Mr. Frith's, now Mr. Frampton's,) one of these mock executions was exposed to the attending crowd. A shutter was fixed horizontally; on the edge of which, after many previous ceremonies, a puppet laid its head, and another puppet then instantly chopped it off with an axe. In a circular staircase-window, at the north end of Sun-court, a similar performance took place by another set of puppets. The condemned puppet bowed its head to the cill which, as above, was soon decapitated. In these representations, the late punishment of the Scotch chieftain (lord Lovat) was alluded to, in order to gratify the feelings of southern loyalty, at the expense of that farther north. —In a fore one-pair room, on the west side of Sun-court, a Frenchman submitted to the curious the astonishing strength of the 'Strong Woman,' his wife. A blacksmith's anvil being procured from White Horse-street, with three of the men, they brought it up, and placed it on the floor. The woman was short, but most beautifully and delicately formed, and of a most lovely countenance. She first let down her hair, (a light auburn.) of a length descending to her knees, which she twisted round the projecting part of the anvil, and then, with seeming ease, lifted the ponderous weight some inches from the floor. After this, a bed was laid in the middle of the room; when, reclining on her back, and uncovering her bosom, the husband ordered the smiths to place thereon the anvil, and forge upon it a horse-shoe! This they obeyed; by taking from the fire a red-hot piece of iron, and with their forging hammers completing the shoe, with the same might and indifference as when in the shop at their constant labour. The prostrate fair one appeared to endure this with the utmost composure, talking and singing during the whole process; then, with an effort which to the by-standers seemed like some supernatural trial, cast the anvil from off her body, jumping up at the same moment with extreme gaiety, and without the least discomposure of her dress or person. That no trick or collusion could possibly be practised on the occasion was obvious, from the following evidence: —The audience stood promiscuously about the room, among whom were our family and friends; the smiths were utter strangers to the Frenchman, but known to us; therefore the several efforts of strength must have proceeded from the natural and surprising power this foreign dame was possessed of. She next put her naked feet on a red-hot salamander, without receiving the least injury: but this is a feat familiar with us at this time. Here this kind of gratification to the senses concluded. —Here, too, was 'Tiddy-doll.

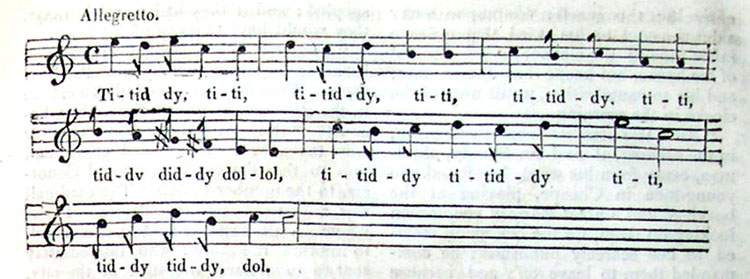

Tiddy Diddy Doll—loll, loll, loll.

This celebrated vender of gingerbread, from his eccentricity of character, and extensive dealings in his way, was always hailed as the king of itinerant tradesmen.* [9] In his person he was tall, well made, and his features handsome. He affected to dress like a person of rank; white gold laced suit of clothes, laced ruffled shirt, laced hat and feather, white silk stockings, with the addition of a fine white apron. Among his harangues to gain customers, take this as a specimen:— 'Mary, Mary, where are you now, Mary? I live, when at home, at the second house in Little Ball-street, two steps under ground, with a wiscum, riscum, and a why-not. Walk in, ladies and gentlemen; my shop is on the second-floor backwards, with a brass knocker at the door. Here is your nice gingerbread, your spice gingerbread; it will melt in your mouth like a red-hot brickbat, and rumble in your inside like Punch and his wheelbarrow.' He always finished his address by singing this fag end of some popular ballad:—

Hence arose his nickname of 'Tiddy-doll.' In Hogarth's print of the execution of the 'Idle 'Prentice,' at Tyburn, Tiddy-doll is seen holding up a gingerbread cake with his left hand, his right being within his coat, and addressing the mob in his usual way:—'Mary, Mary,' &c. His costume agrees with the aforesaid description. For many years, (and perhaps at present,) allusions were made to his name, as thus:—'You are so fine, (to a person dressed out of character,) you look like Tiddy-doll. You are as tawdry as Tiddy-doll. You are quite Tiddy-doll,' &c.—Soon after the late lord Coventry occupied the house, corner of Engine-street, Piccadilly, (built by sir Henry Hunlocke, Bart., on the site of a large ancient inn, called the Greyhound;) he being annoyed with the unceasing uproar, night and day, during the fair, (the whole month of May,) procured, I know not by what means, the entire abolition of this festival of 'misrule' and disorder."

The engraving here given is from an old print of Tiddy-doll; it is presumed, that the readers of the Every-Day Book will look at it with interest.

EVIL MAY-DAY.

In the reign of king Henry VIII., a great jealousy arose in the citizens of London towards foreign artificers, who were then called "strangers." By the interference of Dr. Standish, in a Spital sermon, at Easter, this was fomented into so great rancour, that it violently broke forth in the manner hereafter related by Stow, and occasioned the name of "Evil May-day" to the first of May, whereon the tumult happened. It appears then from him that:—

"The 28th day of April, 1517, divers yong-men of the citie picked quarels with certaine strangers, as they passed along the streets: some they smote and buffetted, and some they threw in the channell: for which, the lord maior sent some of the Englishmen to prison, as Stephen Studley, Skinner, Stevenson, Bets, and other.

"Then suddenly rose a secret rumour, and no man could tell how it began, that on May-day next following, the citie would slay all the aliens: insomuch that divers strangers fled out of the citie.

"This rumour came to the knowledge of the kings councell: whereupon the lord cardinall sent for the maior, and other of the councell of the citie, giving them to understand what hee had heard.

"The lord maior (as one ignorant of the matter) told the cardinall, that he doubted not so to governe the citie, but as peace should be observed.

"The cardinall willed him so to doe, and to take good heed, that if any riotous attempt were intended, he should by good policy prevent it.

"The maior comming from the cardinals house, about foure of the clocke in the afternoone on May eve, sent for his brethren to the Guild-hall, yet was it almost seven of the clocke before the assembly was set. Vpon conference had of the matter, some thought it necessary, that a substantial watch should be set of honest citizens, which might withstand the evill doers, if they went about any misrule. Other were of contrary opinion, as rather thinking it best, that every man should be commanded to shut in his doores, and to keepe his servants within. Before 8 of the clock, master recorder was sent to the cardinall, with these opinions: who hearing the same, allowed the latter. And then the recorder, and sir Thomas More, late under-sheriffe of London, and now of the kings councell, came backe againe to the Guild-hall, halfe an houre before nine of the clock, and there shewed the pleasure of the kings councell: whereupon every alderman sent to his ward, that no man (after nine of the clocke) should stir out of his house, but keepe his doores shut, and his servants within, untill nine of the clocke in the morning.

"After this commandement was given, in the evening, as sir Iohn Mundy, alderman, came from his ward, hee found two young-men in Cheape, playing at the bucklers, and a great many of young-men looking on them, for the commend seemed to bee scarcely published; he commended them to leave off; and because one of them asked him why, hee would have him sent to the counter. But the prentices resisted the alderman, taking the young-man from him, and cryed prentices, prentices, clubs, clubs; then out at every doore came clubs and other weapons, so that the alderman was forced to flight. Then more people arose out of every quarter, and forth came servingmen, watermen, courtiers, and other, so that by eleven of the clocke, there were in Cheape, 6 or 7 hundred, and out of Pauls church-yard came about 300. From all places they gathered together, and brake up the Counter, took out the prisoners, which had been committed thither by the lord maior, for hurting the strangers: also they went to Newgate, and tooke out Studley and Bets, committed thither for the like cause. The maior and sheriffes were present, and made proclamation in the kings name, but nothing was obeyed.

"Being thus gathered into severall heaps, they ran thorow saint Nicholas shambles, and at saint Martins gate, there met with them sir Thomas More, and other, desiring them to goe to their lodgings.

"As they were thus intreating, and had almost perswaded the people to depart, they within saint Martins threw out stones and bats, so that they hurt divers honest persons, which were with sir Thomas More, perswading the rebellious rout to cease. Insomuch as at length, one Nicholas Dennis, a serjeant at arms, being there sore hurt, cryed in a fury, Down with them: and then all the unruly persons ran to the doores and windowes of the houses within St. Martins, and spoiled all that they found. After that they ran into Cornehill, and so on to a house east of Leadenhal, called the Green-gate, where dwelt one Mewtas a Piccard or Frenchman, within whose house dwelled divers French men, whom they likewise spoyled: and if they had found Mewtas, they would have stricken off his head.

"Some ran to Blanchapleton, and there brake up the strangers houses, and spoiled them. Thus they continued till 3 a clocke in the morning, at which time, they began to withdraw: but by the way they were taken by the maior and other, and sent to the Tower, Newgate and Counters, to the number of 300. The cardinall was advertised by sir Thomas Parre, whom in all haste he sent to Richmond, to informe the king: who immediately sent to understand the state of the city, and was truely informed. Sir Roger Cholmeley Lievtenant of the Tower, during the time of this business, shot off certaine peeces of ordnance against the city, but did no great hurt. About five of the clock in the morning, the earles of Shrewsbury and Surrey, Thomas Dockery, lord prior of saint Iohns, George Nevill, lord Aburgaveny, and other, came to London with such powers as they could make, so did the innes of court; but before they came, the business was done, as ye have heard.

"Then were the prisoners examined, and the sermon of doctor Bell called to remembrance, and hee sent to the Tower. A commission of oyer and determiner was directed to the duke of Norfolke, and other lords, for punishment of this insurrection. The second of May, the commissioners, with the lord maior, aldermen, and iustices, went to the Guildhall, where many of the offenders were indicted, whereupon they were arraigned, and pleaded not guilty, having day given them till the 4. of May.

"On which day, the lord maior, the duke of Norfolke, the earle of Surrey and other, came to sit in the Guildhall. The duke of Norfolke entred the city with one thousand three hundred men, and the prisoners were brought through the streets tyed in ropes, some men, some lads but of thirteen of foureteene yeeres old, to the number of 278 persons. That day Iohn Lincolne and divers other were indicted, and the next day thirteen were adjudged to be drawne, hanged, and quartered: for execution whereof, ten payre of gallowes were set up in divers places of the city, as at Aldgate, Blanchapleton, Grasse-street, Leaden-hall, before either of the counters, at Newgate, saint Martins, at Aldersgate and Bishopgate. And these gallowes were set upon wheels, to bee removed from street to street, and from doore to doore, whereas the prisoners were to be executed.

"On the seventh of May, Iohn Lincoln, one Shirwin, and two brethren, named Betts, with divers other were adjudged to dye. They were on the hurdles drawne to the standard in Cheape, and first was Lincolne executed: and as the other had the ropes about their neckes, there came a commandement from the king, to respit the execution, and then were the prisoners sent againe to prison, and the armed men sent away out of the citie.

"On the thirteenth of May, the king came to Westminster-hall, and with him the lord cardinall, the dukes of Norfolke, and Suffolke, the earles of Shrewsbury, Essex, Wiltshire, and Surrey, with many lords and other of the kings councell; the lord maior of London, aldermen and other chiefe citizens, were there in their best liveries, by nine of the clocke in the morning. Then came in the prisoners, bound in ropes in a ranke one after another, in their shirts, and every one had a halter about his necke, being in number 400 men, and 11 women.

"When they were thus come before the kings presence, the cardinall laid sore to the maior and aldermen their negligence, and to the prisoners he delared [sic] how justly they had deserved to dye. Then all the prisoners together cryed to the king for mercy, and there with the lords besought his grace of pardon: at whose request, the king pardoned them all. The generall pardon being pronounced, all the prisoners shouted at once, and cast their halters towards the roofe of the hall. The prisoners being dismissed, the gallowes were taken downe, and the citizens tooke more heed to their servants: keeping (for ever after) as on that night, a strong watch in Armour, in remembrance of Evill May-day.