November 28.

St. Stephen the Younger, A. D. 764. St. James of La Marea, of Ancona, A. D. 476.

[Michaelmas Term ends.]

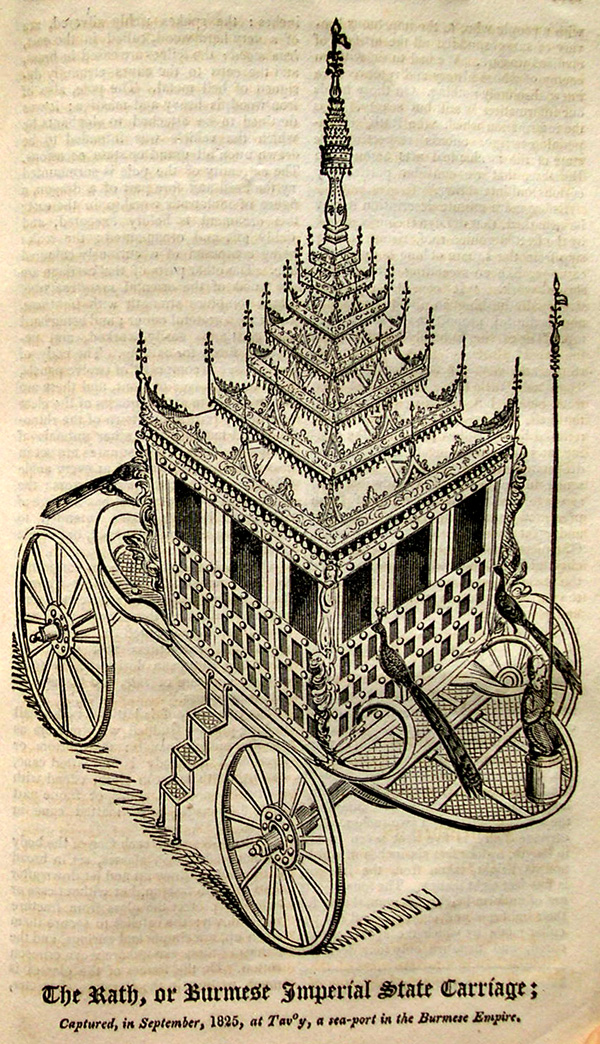

BURMESE STATE CARRIAGE.Exhibited in November, 1825.

An invitation to a private view of the "Rath," or state carriage of the king of Ava, or emperor of the Burmans, at the Egyptian-hall, Piccadilly, gave the editor of the Every-Day Book an opportunity of inspecting it, on Friday, the 18th of November, previous to its public exhibition; and having been accompanied by an artist, for whom he obtained permission to make a drawing of the splendid vehicle, he is enabled to present the accompanying engraving.

The Times, in speaking of it, remarks, that "The Burmese artists have produced a very formidable rival to that gorgeous piece of lumber, the lord mayor's coach. It is not indeed quite so heavy, nor quite so glassy as that moving monument of metropolitan magnificence; but it is not inferior to it in glitter and in gilding, and is far superior in the splendour of the gems and rubies which adorn it. It differs from the metropolitan carriage in having no seats in the interior, and no place for either sword-bearer, chaplain, or any other inferior officer. The reason of this is, that whenever the 'golden monarch' vouchsafes to show himself to his subjects, who with true legitimate loyalty worship him as an emanation from the deity, he orders his throne to be removed into it, and sits thereon, the sole object of their awe and admiration."

The Rath, or Burmese Imperial State Carriage;[1]

Captured, in September, 1825, at Tav°y, a sea-port in the Burmese Empire.

The British Press well observes, that "Independent of the splendour of this magnificent vehicle, its appearance in this country at the present moment is attended with much additional and extrinsic interest. It is the first specimen of the progress of the arts in a country of the very existence of which we appeared to be oblivious, till recent and extraordinary events recalled it to our notice. The map of Asia alone reminded us that an immense portion of the vast tract of country lying between China and our Indian possessions, and constituting the eastern peninsula of India, was designated by the name of the Burmah empire. But so little did we know of the people, or the country they inhabited, that geographers were not agreed upon the orthography of the name. The attack upon Chittagong at length aroused our attention to the concerns of this warlike people, when one of the first intimations we received of their existence was the threat, after they had expelled us from India, to invade England. Our soldiers found themselves engaged in a contest different from any they had before experienced in that part of the world, and with a people who, to the impetuous bravery of savages, added all the artifices of civilized warfare. We had to do with an enemy of whose history and resources we knew absolutely nothing. On those heads our information is still but scanty. It is the information which 'the Rath,' or imperial carriage, affords respecting the state of the mechanical arts among the Burmese, that we consider particularly curious and interesting."

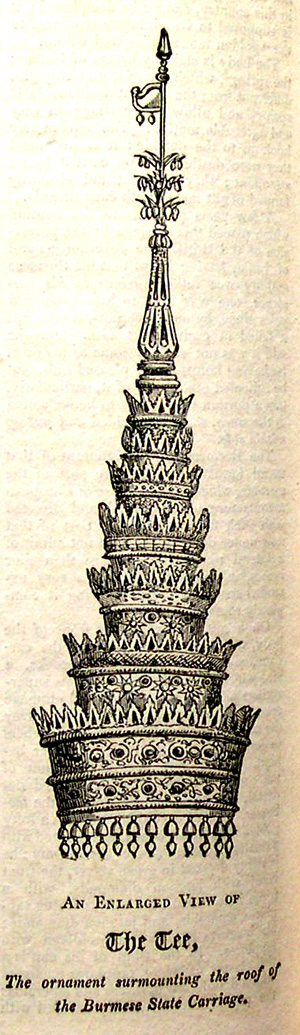

Before more minute description it may be remarked, that the eye is chiefly struck by the fretted golden roof, rising step by step from the square oblong body of the carriage, like an ascending pile of rich shrine-work. "It consists of seven stages, diminishing in the most skilful and beautiful proportions towards the top. The carving is highly beautiful, and the whole structure is set thick with stones and gems of considerable value. These add little to the effect when seen from below, but ascending the gallery of the hall, the spectator observes them, relieved by the yellow ground of the gilding, and sparkling beneath him like dew-drops in a field of cowslips. Their presence in so elevated a situation well serve to explain the accuracy of finish preserved throughout, even in the nicest and most minute portions of the work. Gilt metal bells, with large heart-shaped chrystal drops attached to them, surround the lower stages of the pagoda, and, when the carriage is put in motion, emit a soft and pleasing sound."*[2] The apex of the roof is a pinnacle, called the tee, elevated on a pedestal. The tee is an emblem of royalty. It is formed of movable belts, or coronals, of gold, wherein are set large amethysts of a greenish or purple colour: its summit is a small banner, or vane, of crystal.

The length of the carriage itself is thirteen feet seven inches; or, if taken from the extremity of the pole, twenty-eight feet five inches. Its width is six feet nine inches, and its height, to the summit of the tee, is nineteen feet two inches. The carriage body is five feet seven inches in length, by four feet six inches in width, and its height, taken from the interior, is five feet eight inches. The four wheels are of uniform height, are remarkable for their lightness and elegance, and the peculiar mode by which the spokes are secured, and measure only four feet two inches: the spokes richly silvered, are of a very hard wood, called in the east, iron wood: the felloes are cased in brass, and the caps to the naves elegantly designed of bell metal. The pole, also of iron wood, is heavy and massive; it was destined to be attached to elephants by which the vehicle was intended to be drawn upon all grand or state occasions. The extremity of the pole is surmounted by the head and fore part of a dragon, a figure of idolatrous worship in the east; this ornament is boldly executed, and richly gilt and ornamented; the scales being composed of a curiously coloured talc. The other parts of the carriage are the wood of the oriental sassafras tree, which combines strength with lightness, and emits a grateful odour; and being hard and elastic, is easily worked, and peculiarly fitted for carving. The body of the carriage is composed of twelve panels, three on each face or front, and these are subdivided into small squares of the clear and nearly transparent horn of the rhinoceros and buffalo, and other animals of eastern idolatry. These squares are set in broad gilt frames, studded at every angle with raised silvered glass mirrors: the higher part of these panels has a range of rich small looking-glasses, intended to reflect the gilding of the upper, or pagoda stages.

The whole body is set in, or supported by four wreathed dragon-like figures, fantastically entwined to answer the purposes of pillars to the pagoda roof, and carved and ornamented in a style of vigour and correctness that would do credit to a European designer: the scaly or body part are of talc, and the eyes of pale ruby stones.

The interior roof is latticed with small looking-glasses studded with mirrors as on the outside panels: the bottom or flooring of the body is of matted cane, covered with crimson cloth, edged with gold lace, and the under or frame part of the carriage is of matted cane in panels.

The upper part of each face of the body is composed of sash glasses, set in broad gilt frames, to draw up and let down after the European fashion, but without case or lining to protect the glass from fracture when down; the catches to secure them when up, are simple and curious, and the strings of these glasses are wove crimson cotton. On the frames of the glasses is much writing in the Burmese character, but the language being utterly unknown in this country, cannot be deciphered; it is supposed to be adulatory sentences to the "golden monarch" seated within.

The body is staid by braces of leather; the springs, which are of iron, richly gilt, differ not from the present fashionable C spring, and allow the carriage an easy and agreeable motion. The steps merely hook on to the outside: it is presumed they were destined to be carried by an attendant; they are light and elegantly formed of gilt metal, with cane threads.

A few years previous to the rupture which placed this carriage in the possession of the British, the governor-general of India, having heard that his Burmese majesty was rather curious in his carriages, one was sent to him some few years since, by our governnor-general, but it failed in exciting his admiration—he said it was not so handsome as his own. It having lamps rather pleased him, but he ridiculed other parts of it, particularly, that a portion so exposed to being soiled as the steps, should be folded and put up within side.

The Burmese are yet ignorant of that useful formation of the fore part of the carriage, which enables those of European manufacture to be turned and directed with such facility: the fore part of that now under description, does not admit of a lateral movement of more than four inches, it therefore requires a very extended space in order to bring it completely round.

On a gilt bar before the front of the body, with their heads towards the carriage, stand two Japanese peacocks, a bird which is held sacred by this superstitious people; their figure and plumage are so perfectly represented, as to convey the natural appearance of life; two others to correspond are perched on a bar behind. On the fore part of the frame of the carriage, mounted on a silvered pedestal, in a kneeling position, is the tee-bearer, a small carved image with a lofty golden wand in his hands, surmounted with a small tee, the emblem of sovereignty: he is richly dressed in green velvet, the front laced with jargoon diamonds, with a triple belt round the body, of blue sapphires, emeralds, and jargoon diamonds; his leggings are also embroidered with sapphires. In the front of his cap is a rich cluster of white sapphires encircled with a double star of rubies and emeralds: the cap is likewise thickly studded with the carbuncle, a stone little known to us, but in high estimation with the ancients. Behind the carriage are two figures; their lower limbs are tattooed, as is the custom with the Burmese: from their position, being on one knee, their hands raised and open, and their eyes directed as in the act of firing, they are supposed to have borne a representation of the carbine, or some such fire-arm weapon of defence, indicative of protection.

The pagoda roof constitutes the most beautiful, and is, in short, the only imposing ornament of the carriage. The gilding is resplendent, and the design and carving of the rich borders which adorn each stage are no less admirable. These borders are studded with amethysts, emeralds, jargoon diamonds, garnets, hyacinths, rubies, tourmalines, and other precious gems, drops of amber and crystal being also interspersed. From every angle ascends a light spiral gilt ornament, enriched with crystals and emeralds.

This pagoda roofing, as well as that of the great imperial palace, and of the state war-boat or barge, bears an exact similitude to the chief sacred temple at Shoemadro. The Burman sovereign, the king of Ava, with every eastern Bhuddish monarch, considers himself sacred, and claims to be worshipped in common with deity itself; so that when enthroned in his palace, or journeying on warlike or pleasurable excursions in his carriage, he becomes an object of idolatry.

The seat or throne for the inside is movable, for the purpose of being taken out and used in council or audience on a journey. It is a low seat of cane-work, richly gilt, folding in the centre, and covered by a velvet cushion. The front is studded with almost every variety of precious stone, disposed and contrasted with the greatest taste and skill. The centre belt is particularly rich in gems, and the rose-like clusters or circles are uniformly composed of what is termed the stones of the orient: viz. pearl, coral, sapphire, cornelian, cat's-eye, emerald, and ruby. A range of buffalo-horn panels ornament the front and sides of the throne, at each end of which is a recess, for the body of a lion like jos-god figure, called Sing, a mythological lion, very richly carved and gilt; the feet and teeth are of pearl; the bodies are covered with sapphires, hyacinths, emeralds, tourmalines, carbuncles, jargoon diamonds, and rubies; the eyes are of a tri-coloured sapphire. Six small carved and gilt figures in a praying or supplicatory attitude, are fixed on each side of the seat of the throne, they may be supposed to be interceding for the mercy or safety of the monarch: their eyes are rubies, their drop ear-rings cornelian, and their hair the light feather of the peacock.

The chattah, or umbrella, which overshadows the throne, is an emblem or representation of regal authority and power.

It is not to be doubted, that the caparisons of the elephants would equal in splendour the richness of the carriage, but one only of the elephants belonging to the carriage was captured; the caparisons for both are presumed to have escaped with the other animal. It is imagined that the necks of these ponderous beings bore their drivers, with small hooked spears to guide them, and that the cortêge combined all the great officers of state, priests, and attendants, male and female, besides the imperial body-guard mounted on eighty white elephants.

Among the innumerable titles, the emperor of the Burmans styles himself "king of the white elephant." Xacca, the founder of Indian idolatry, is affirmed by the Brahmins to have gone through a metampsychosis eighty thousand times, his soul having passed into that number of brutes; that the last was in a white elephant, and that after these changes he was received into the company of the gods, and is now a pagod.

This carriage was taken with the workmen who built it, and all their accounts. From these it appeared, that it had been three years in building, that the gems were supplied from the king's treasury, or by contribution from the various states, and that the workmen were remunerated by the government. Independent of these items, the expenses were stated in the accounts to have been twenty-five thousand rupees, (three thousand one hundred and twenty-five pounds.) The stones are not less in number than twenty thousand, which its reputed value at Tavoy was a lac of rupees, twelve thousand five hundred pounds.

AN ENLARGED VIEW OF

The Tee,

The ornament surmounting the roof of

the Burmese State Carriage.[3]It was in August, 1824, that the expedition was placed under the command of lieutenant-colonel Miles, C. B., a distinguished officer in his majesty's service. It comprised his majesty's 89th regiment, 7th Madras infantry, some artillery, and other native troops, amounting in the whole to about one thousand men. The naval force, under the command of captain Hardy, consisted of the Teignmouth, Mercury, Thetis, Panang cruiser Jesse, with three gun boats, three Malay prows, and two row boats. The expedition sailed from Rangoon on the 26th of August, and proceeded up the Tavoy river, which is full of shoals and natural difficulties. On the 9th of September, Tavoy, a place of considerable strength, with ten thousand fighting men, and many mounted guns, surrendered to the expedition. The viceroy of the province, his son, and other persons of consequence, were among the prisoners, and colonel Miles states in his despatch, that, with the spoil, he took "a new state carriage for the king of Ava, with one elephant only." This is the carriage now described. After subsequent successes the expedition returned to Rangoon, whither the carriage was also conveyed; from thence, it was forwarded to Calcutta, and there sold for the benefit of the captors. The purchaser, judging that it would prove an attractive object of curiosity in Europe, forwarded it to London, by the Cornwall, captain Brooks, and it was immediately conveyed to the Egyptian-hall for exhibition. It is not too much to say that it is a curiosity. A people emerging from the bosom of a remote region, wherein they had been concealed until captain Symes's embassy, and struggling in full confidence against British tactics, must, in every point of view, be interesting subjects of inquiry. The Burmese state carriage, setting aside its attractions as a novelty, is a remarkable object for a contemplative eye.

Unlike Asiatics in general, the Burmese are a powerful, athletic, and intelligent men. They inhabit a fine country, rich in rivers and harbours. It unites the British possessions in India with the immense Chinese empire. By incessant encroachments on surrounding petty states, they have swallowed them up in one vast empire. Their jealousy, at the preponderance of our eastern power, has been manifested on many occasions. They aided the Mahratta confederacy; and if the promptness of the marquis of Hastings had not deprived them of their allies before they were prepared for action, a diversion would doubtless have then been made by them on our eastern frontier[.]

Burmah is the designation of an active and vigorous race, originally inhabiting the line of mountains, separating the great peninsula, stretching from the confines of Tartary to the Indian Ocean, and considered, by many, the Golden Chersonesus of the ancients. From their heights and native fastnesses, this people have successively fixed their yoke upon the entire peninsula of Aracan, and after seizing successively the separate states and kingdoms of Ava, Pegue, &c., have condensed their conquests into one powerful state, called the Burmah empire, from their own original name. This great Hindoo-Chinese country, has gone on extending itself on every possible occasion. They subdued Assam, a fertile province of such extent, as to include an area of sixty thousand square miles, inhabited by a warlike people who had stood many powerful contests with neighbouring states. On one occasion, Mohammed Shar, emperor of Hindostan, attempted to conquer Assam with one hundred thousand cavalry; the Assamese annihilated them. The subjugation of such a nation, and constant aggressions, have perfected the Burmese in every species of attack and defence: their stockade system, in a mountainous country, closely intersected with nullahs, or thick reedy jungles, sometimes thirty feet in height, has attained the highest perfection. Besides Aracan, they have conquered part of Siam, so that on all sides the Burmese territory appears to rest upon natural barriers, which might seem to prescribe limits to its progress, and ensure repose and security to its grandeur. Towards the east, immense deserts divide its boundaries from China; on the south, it has extended itself to the ocean; on the north, it rests upon the high mountains of Tartary, dividing it from Tibet; on the west, a great and almost impassable tract of jungle wood, marshes, and alluvial swamps of the great river Houghly, or the Ganges, has, till now, interposed boundaries between itself and the British possessions. Beyond this latter boundary and skirting of Assam is the district of Chittagong, the point whence originated the contest between the Burmese and the British.

The Burmese population is estimated at from seventeen to nineteen millions of people, lively, industrious, energetic, further advanced in civilization than most of the eastern nations, frank and candid, and destitute of that pusillanimity which characterises the Hindoos, and of that revengefull malignity which is a leading trait in the Malay character. Some are even powerful logicians, and take delight in investigating new subjects, be they ever so abstruse. Their learning is confined to the male sex, and the boys are taught by the priests. Females are denied education, except in the higher classes. Their books are numerous, and written in a flowing and elegant style, and much ingenuity is manifested in the construction of their stories.

The monarch is arbitrary. He is the sole lord and proprietor of life and property in his dominions; his word is absolute law. Every male above a certain age is a soldier, the property of the sovereign, and liable to be called into service at any moment.

The country presents a rich and beautiful appearance, and, if cultivated, would be one of the finest in the world. Captain Cox says, "wherever I have landed, I have met with security and abundance, the houses and farmyards put me in mind of the habitations of our little farmers in England."

There is a variety of other information concerning this extraordinary race, in the interesting memoir which may be obtained at the rooms in Piccadilly. These were formerly occupied by "Bullock's Museum." Mr. Bullock, however, retired to Mexico, to form a museum in that country for the instruction of its native population; and Mr. George Lackington purchased the premises in order to let such portions as individuals may require, from time to time, for purposes of exhibition, or as rooms for the display and sale of works in the fine arts, and other articles of refinement. Mr. Day's "Exhibition of the Moses of the Vatican," and other casts from Michael Angelo, with numerous subjects in sculpture and painting, of eminent talent, remains under the same roof with the Burmese carriage, to charm every eye that can be delighted by magnificent objects.

Advent.

This term denotes the coming of the Saviour. In ecclesiastical language it is the denomination of the four weeks preceding the celebration of his birthday. In the Romish church this season of preparation for Christmas is a time of penance and devotion. It consists of four weeks, or at least four Sundays, which commence from the Sunday nearest to St. Andrew's day, whether before or after it: anciently it was kept as a rigorous fast.*[4]

In the church of England it commences at the same period. In 1825, St. Andrew's day being a fixed festival on the 30th of November, and happening on a Wednesday, the nearest Sunday to it, being the 27th of November, was the first Sunday in Advent; in 1826, St. Andrew's day happening on a Thursday, the nearest Sunday to it is on the 3d of December, and, therefore, the first Sunday in Advent.

New Annual Literature.

THE AMULET.

The literary character and high embellishment of the German almanacs, have occasioned an annual publication of beautifully printed works for presents at this season. The Amulet, for 1826, is of this order. Its purpose is to blend religious instruction with literary amusement. Messrs. W. L. Bowles, Milman, Bowring, Montgomery, Bernard, Barton, Conder, Clare, T. C. Croker, Dr. Anster, Mrs. Hofland, &c.; and, indeed, individuals of various denominations, are contributors of sixty original essays and poems to this elegant volume, which is embellished by highly finished engravings from designs by Martin, Westall, Brooke, and other painters of talent. Mr. Martin's two subjects are engraved by himself in his own peculiarly effective manner. Hence, while the Amulet aims to inculcate the fitness of Christian precepts, and the beauty of the Christian character, it is a specimen of the progress of elegant literature and fine art.

The Amulet contains a descriptive poem, wherein the meaning of the word advent is exemplified; it commences on the next page.

THE RUSTIC FUNERAL.

A Poetical Sketch.

BY JOHN HOLLAND.

'Twas Christmas—and the morning of that day,

When holy men agree to celebrate

The glorious advent of their common Lord,

The Christ of God, the Saviour of mankind!

I, as my wont, sped forth, at early dawn,

To join in that triumphant natal hymn,

By Christians offer'd in the house of prayer.

Full of these thoughts, and musing of the theme,

The high, the glorious theme of man's redemption,

As I pass'd onward through the village lane,

My eye was greeted, and my mind was struck,

By the approach of a strange cavalcade,—

If cavalcade that might be called, which here

Six folks composed—the living and the dead.

It was a rustic funeral, off betimes

To some remoter village. I have seen

The fair or sumptuous, yea, the gorgeous rites,

The ceremonial, and the trappings proud,

With which the rich man goeth to the dust;

And I have seen the pauper's coffin borne

With quick and hurried step, without a friend

To follow—one to stand on the grave's brink,

To weep, to sigh, to steal one last sad look,

Then turn away for ever from the sight.

But ne'er did pompous funeral of the proud,

Nor pauper's coffin unattended borne,

Impress me like this picturesque array.

Upright and tall, the coffin-bearer, first

Rode, mounted on an old gray, shaggy ass;

A cloak of black hung from his shoulders down,

And to the hinder fetlocks of the beast

Depended, not unseemly: from his hat

A long crape streamer did the old man wear,

Which ever and anon play'd with the wind:

The wind, too, frequently blew back his cloak,

And then I saw the plain neat oaken coffin,

Which held, perchance, a child of ten years old.

Around the coffin, from beneath the lid,

Appear'd the margin of a milk-white shroud,

All cut, and crimp'd, and pounc'd with eyelet-holes

As well became the last, last earthly robe

In which maternal love its object sees.

A couple follow'd, in whose looks I read

The recent traces of parental grief,

Which grief and agony had written there.

A junior train—a little boy and girl,

Next follow'd, in habiliments of black;

And yet with faces, which methought bespoke

Somewhat of pride in being marshall'd thus,

No less than decorous and demure respect.

The train pass'd by: but onward as I sped,

I could not raze the picture from my mind;

Nor could I keep the unavailing wish

That I had own'd albeit but an hour,

Thy gifted pencil, Stothard!—rather still,

That mine had match'd thy more than graphic pen,

Descriptive Wordsworth! This at least I claim,

Feebly, full feebly to have sketch'd a scene,

Which, 'midst a thousand recollections stor'd

Of village sights, impress'd my pensive mind

With some emotions ne'er to be forgot.Sheffield Park.[5]

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Variegated Stapelia. Stapelia variegata.

Dedicated to St. Stephen, the younger.