September 19.

St. Januarius, Bp. of Benevento, A. D. 305. St. Theodore, Abp. of Canterbury, A. D. 690. Sts. Peleus, Pa-Termuthes, and Companions. St. Lucy, A. D. 1090. St. Eustochius, Bp. A. D. 461. St. Sequanus, or Seine, Abbot, A. D. 580.

STOURBRIDGE FAIRThis place, near Cambridge, is also called Sturbridge, Sturbritch, and Stirbitch. A Cambridge newspaper speaks of Stirbitch fair being proclaimed on the 19th of September, 1825, for a fortnight, and of Stirbitch horse-fair commencing on the 26th of the month. The corruption of this proper name, stamps the persons who use it in its vulgar acceptation as being ignorant as the ignorant; the better instructed should cease from shamefully acquiescing in the long continued disturbance of this appelation.

Stephen Batman, in his "Doome warning," published in 1582, relates that "Fishers toke a disfigured divell, in a certain stoure, (which is a mighty gathering togither of waters, from some narrow lake of the sea,) a horrible monster with a goats heade, and eyes shyning lyke fyre, whereuppon they were all afrayde and ranne awaye; and that ghoste plunged himselfe under the ise, and running uppe and downe in the stowre made a terrible noyse and sound." We get in Stirbitch a most "disfigured divell" from Stourbridge. The good people derive their "good name" from their river.

Stourbridge fair originated in a grant from king John to the hospital of lepers at that place. By a charter in the 30th year of Henry VIII., the fair was granted to the magistrates and corporation of Cambridge. The vicechancellor of the university has the same power in it that he has in the town of Cambridge.

By an order of privy council of the 3rd of October, 1547, the mayor and under-sheriff of the county were required, not only to acknowledge before the vicechancellor, heads of colleges and proctors, that they had interfered with the privileges of the university in Stourbridge fair, but also, "that the mayor, in the common hall, shall openly, among his brethren, acknowledge his wilfull proceeding." The breach consisted in John Fletcher, the mayor, having refused to receive into the tolbooth certain persons of "naughty and corrupt behaviour," who were "prisoners, taken by the proctors of the university, in the last Sturbridge fair;" wherefore he was called before the lords and others of the council, and his fault therein "so plainly and justly opened" that he could not deny it, but did "sincerely and willingly confess his said fault."*[1]

In 1613, Stourbridge fair acquired such celebrity, that hackney-coaches attended it from London. Subsequently not less than sixty coaches plied at this fair, which was the largest in England. Vast quantities of butter and cheese found there a ready market; it stocked the people of Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, and other counties with clothes, and all other necessaries; and shopkeepers supplied themselves from thence with the commodities wherein they dealt.† [2]

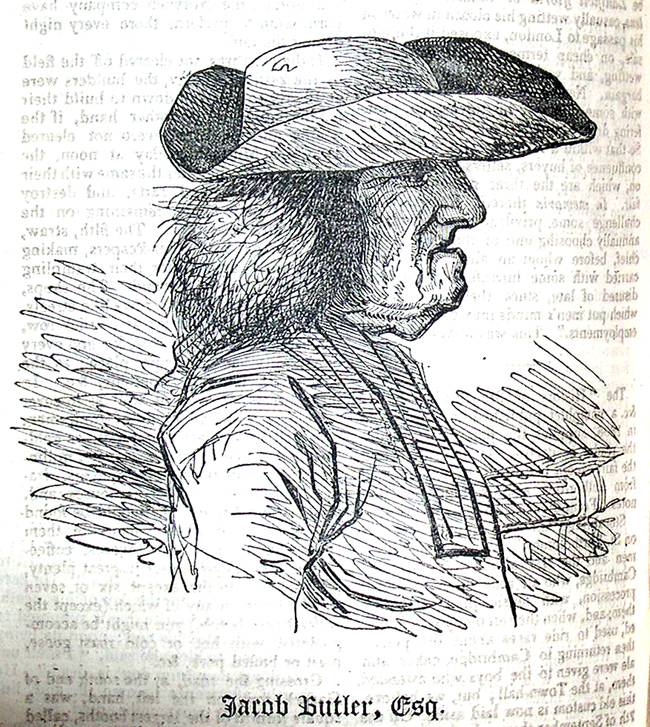

Jacob Butler, Esq. who died on the 28th of May, 1765, stoutly maintained the charter of Stourbridge fair: he was of Bene't-college, Cambridge, and a barrister-at-law. In stature he was six feet four inches high, of determined character, and deemed "a great eccentric" because, among other reasons, he usually invited the giants and dwarfs, who came for exhibition, to dine with him. He was so rigid in seeing the charter literally complied with, that if the ground was not cleared by one o'clock on the day appointed, and he found any of the booths standing, he had them pulled down, and the materials taken away. On one occasion when the wares were not removed by the time mentioned in the charter, he drove his carriage among the crockery and destroyed a great quantity.

The rev. John Butler, LL. D. rector of Wallington, in Hertfordshire, father of Mr. Butler, who was his eldest son, endeavoured in the year 1705, to get Stourbridge fair rated to the poor. This occasioned a partial and oppressive assessment on himself that involved him in great difficulties. Dr. Butler died in 1714, and Jacob Butler succeeded to his difficulties and estates in the parish of Barnwell. As a trustee under an act for the turnpike road from Cambridge to London, Mr. Butler was impeached of abuses in common with his co-trustees. Being obnoxious, he was singled out to make good the abuse, and summoned to the county sessions, where he appeared in his barrister's gown, was convicted and fined ten pounds, which he refused to pay, and was committed. He excepted to the jurisdiction, wherein he was supported by the opinion of sir Joseph Yorke, then attorney-general, and to save an estreat applied to the under-sheriff, who refused his application, and afterwards went to the clerk of the peace at Newmarket, from whom he met the like treatment; this forced him to the quarter-sessions, where he obtained his discharge, after telling the chairman he felt it hard to be compelled to the trouble and expense of teaching him and his brethren law. He appears to have been a lawyer of that school, which admitted no law but the old common law of the land, and statute law. In 1754, "to stem the venality and corruption of the times, he offered himself a candidate to represent the county in parliament, unsupported by the influence of the great, the largess of the wealthy, or any interest, but that which his single character could establish in the esteem of all honest men and lovers of their country. But when he found the struggles for freedom faint and ineffectual, and his spirits too weak to resist the efforts of his enemies, he contented himself with the testimony of those few friends who dare to be free, and of his own unbiassed conscience, which, upon this, as well as every other occasion, voted in his favour; and upon these accounts he was justly entitled to the name of the old Briton." He bore this appellation to the day of his death. The loss of a favourite dog is supposed to have accelerated his end; upon its being announced to him, he said, "I shall not live long now my dog is dead." He shortly afterwards became ill, and, lingering about two months, died.

His coffin, which was made from a large oak by his express order, some months before his death, became an object of public curiosity; it was of sufficient dimensions to contain several persons, and wine was copiously quaffed therein by many of those who went to see it. To a person, who was one of the legatees, the singular trust was delegated of driving him to the grave, on the carriage of a waggon, divested of the body: seated in the front, he was to drive his two favourite horses, Brag and Dragon, to Barnwell church, and should they refuse to receive his body there, he was to return and bury him in the middle of the grass-plat in his own garden. Part only of his request was complied with, for the body being put into a leaden coffin, and the leaden one into a shell, was conveyed in a hearse, and the coffin made before his death was put upon the carriage of his waggon, and driven before the hearse by the gentleman above mentioned; when arrived at the church door, it was taken from the carriage by four men, who received half-a-guinea each; it was then put into the vault, and the corpse being taken from the hearse was carried to the vault, there put into the coffin, and then screwed down.

The late rev. Michael Tyson of Bene't-college, "a good antiquary and a gentleman artist," amused himself with etching a few portraits; among them were some of the old masters of his college, and some of the noted characters in and about Cambridge, as Jacob Butler of Barnwell, who called himself the ["]old Briton," which Mr. Nichols says "may be called his best, both in design and execution; for it expresses the very man himself." A gentleman of the university has obligingly communicated to this work a fine impression of Mr. Tyson's head of "the old Briton," from whence the present portrait is engraven.

Origin of Stourbridge Fair.

Mr. George Dyer, in a supplement to his recently published "Privileges of the University of Cambridge," being a sequel to his "History of the University," cites thus from Fuller:—

"Stourbridge fair is so called from Stour, a little rivulet (on both sides whereof it is kept,) on the east of Cambridge, whereof this original is reported. A clothier of Kendal, a town characterized to be Lanificii gloria et industria prœcellens, casually wetting his cloath in water in his passage to London, exposed it there to sale, on cheap termes, as the worse for wetting, and yet it seems saved by the bargain. Next year he returned again with some other of his townsmen, proffering drier and dearer cloath to be sold. So that within a few years hither came a confluence of buyers, sellers, and lookers-on, which are the three principles of a fair. In memoria thereof, Kendal men challenge some privilege in that place, annually choosing one of the town to be chief, before whom an antic sword was carried with some mirthful solemnities, disused of late, since these sad times, which put men's minds into more serious employments." This was about 1417.

The "History of Stourbridge Fair," &c. a pamphlet published at Cambridge in 1806, supplies the particulars before the reader, respecting Jacob Butler and the fair, except in a few instances derived from authorities acknowledged in the notes. From thence also is as follows:—

Stourbridge fair was annually set out on St. Bartholomew's day, by the aldermen and the rest of the corporation of Cambridge, who all rode there in grand procession, with music playing before them; and, when the ceremony was finished, used to ride races about the place; then returning to Cambridge, cakes and ale were given to the boys who attended them, at the Town-hall; but, we believe, this old custom is now laid aside. On the 7th of September they rode in the same manner to proclaim it; which being done, the fair then began, and continued three weeks, though the greatest part was over in a fortnight.

This fair, which was allowed, some years ago, to be the largest in Europe, is kept in a corn-field about half a mile square, the river Cam running on the north side, and the rivulet called the Stour, (from which, and the bridge which crosses it, the fair received its name,) on the east side; it is about two miles from Cambridge market-place, and where, during the time of the fair, coaches, &c. attend to convey persons to the fair. The chief diversions at the fair were drolls, rope-dancing, sometimes a music-booth, and plays performed; and though there is an act of parliament which prohibits the acting of plays within ten miles of Cambridge, the Norwich company have permission to perform there every night during the fair.

If the corn was not cleared off the field by the 24th of August, the builders were at liberty to tread it down to build their booths; and on the other hand, if the booths and materials were not cleared away by Michaelmas-day at noon, the ploughmen might enter the same with their horses, ploughs, and carts, and destroy whatever they found remaining on the ground after that time. The filth, straw, dung, &c. left by the fair-keepers, making the farmers amends for their trampling and hardening the ground. The shops, or booths, were built in rows like streets, having each their name; as Garlick-row, Booksellers'-row, Cook-row, &c. and every commodity had its proper place; as the cheese-fair, hop-fair, wool-fair, &c. In these streets, or rows, as well as in several others, were all kinds of tradesmen, who sell by wholesale or retail, as goldsmiths, toy-men, barziers, turners, milliners, haberdashers, hatters, mercers, drapers, pewterers, china warehouses, and, in short, most trades that could be found in London, from whence many of them came; there were also taverns, coffee-houses, and eating-houses in great plenty, all kept in booths, except six or seven brick-houses, in any of which (except the coffee-house booth,) you might be accomodated with hot or cold roast goose, roast or boiled pork, &c.

Crossing the road, at the south end of Garlick-row, on the left hand, was a square formed of the largest booths, called the Duddery, the area of which was from two hundred and forty to three hundred feet, chiefly taken up with woollen drapers, wholesale tailors, sellers of second-hand clothes, &c. where the dealers had a room before their booths to take down and open their packs, and bring in waggons to load and unload the same. In the centre of the square there formerly stood a high pole with a vane at the top. On two Sundays, during the principal time of the fair, morning and afternoon, divine service was performed, and a sermon preached by the minister of Barnwell, from a pulpit placed in this square, who was very well paid for the same, by a contribution made among the fair-keepers.

In this duddery only, it is said, that 100,000l. worth of woollen manufacture has been sold in less than a week, exclusive of the trade carried on here by the wholesale tailors from London, and other parts of England, who transacted their business wholly with their pocket-books, and meeting with their chapmen here from all parts of the country, make up their accounts, receive money, and take further orders. These, it is said, exceed the sale of goods actually brought to the fair, and delivered in kind; it was frequently known that the London wholesale-men have carried back orders from their dealers for 10,000l. worth of goods, and some a great deal more. Once, in this duddery, there was a booth consisting of six apartments, which contained goods worth 20,000l. belonging solely to a dealer in Norwich stuffs.

The trade for wool, hops, and leather, was prodigious; the quantity of wool only, which was sold at one fair, was said to amount to between 50 and 60,000l., and of hops to nearly the same sum.

The 14th of September was the horse-fair day, which was always the busiest day during the time of the fair, and the number people, who came from all parts of the county on this day, was very great. Colchester oysters and fresh herrings were in great request, particularly by those who lived in the inland parts of the kingdom.

The fair was like a well-governed city, and less disorder or confusion were to be seen here than in any other place, where there was so great a concourse of people assembled. Here was a court of justice, open from morning till night, where the mayor or his deputy, always attended to determine all controversies in matters arising from the business of the fair, and for keeping the peace; for which purpose he had eight servants to attend him, called red-coats, who were employed as constables, and if any dispute arose between buyer and seller, &c. upon calling out red-coat there was one of them immediately to hand; and if the dispute was not quickly decided, the offenders were taken to the said court, and the case determined in a summary way, (as was practised in those called pie-powder courts in other fairs,) and from which there was no appeal.

The greatest inconvenience attending the tradesmen at this fair, was the manner in which they were obliged to lodge in the night; their bed (if it may be so called,) was laid upon two or three boards nailed to four posts about a foot from the ground, and four boards fixed round it to keep them from falling out; in the day-time it was obliged to be removed from the booth, and laid in the open air, exposed to the weather; at night it was again taken in, and made up in the best manner they were able, and they laid almost neck and heels together, it being not more than five feet long. Very heavy rains, which fall about this season, would sometimes force through the hair-cloths, which were almost the only covering to the booths, and oblige them to get up again; and high winds have been known to blow down many of the booths, particularly in the year 1741.

CRUELTY TO ANIMALS.

Legislative discussion and interference have raised a feeling of kindness towards the brute creation which slumbered and slept in our forefathers. Formerly, the costermonger was accustomed to make wounds for the express purpose of producing torture. He prepared to drive an ass, that had not been driven, with his knife. On each side of the back bone, at the lower end, just above the tail, he made an incision of two or three inches in length through the skin, and beat into these incisions with his stick till they became open wounds, and so remained, while the ass lived to be driven to and from market, or through the streets of the metropolis. A costermonger, now, would shrink from this, which was a common practice between the years 1790 and 1800. The present itinerant venders of apples, and other fruit, abstain from wanton barbarity, while coachmen and carmen are punished for it under Mr. Martin's act. This gentleman's humanity, though sometimes eccentric, is ever active; and, when judiciously exercised, is approved by natural feelings, and supported by public opinion.

A correspondent has pleasantly thrown together some amusing citations respecting the ass. It is a rule with the editor of the Every-Day Book not to alter communications, or he would have turned one expression, in the course of the subjoined paper, which seems to bear somewhat ludicrously upon the interference of the member for Galway, in behalf of that class of animals which have endured more persecution than any in existence, except, perhaps, our fellow human-beings, the Jews.

THE ASS.

(For Hone's Every-Day Book.)

Poorly as the world may think of the intellectual abilities of asses, there have been some very clever fellows among them. There have been periods when, far from his name being synonymous with stupidity, and his person made the subject of the derision, the contempt, and, what is worse, the scourge of the vulgar—(for that is "the unkindest cut of all")—he was "respected and beloved by all who had the pleasure of his acquaintance!" Leo Africanus asserts, that asses may be taught to dance to music, and it is surprising to see the accurate manner in which they will keep time. In this, at least, they must be far superior to us, poor human beings, if they can keep time, for "time stays for no man," as the proverb says. Though their vocal powers do not equal those of a Bra-ham, yet we have had an undoubted proof of the sensitiveness of their ear to the sweets of harmony; Gay also tells us—

"The ass learnt metaphors and tropes,

But most on music fixed his hopes."—And merry Peter Pindar thus apostrophises his asinine namesake:—

"What tho' I've heard some voices sweeter;

Yet exquisite thy hearing, gentle Peter!

Whether a judge of music, I don't know—

If so—

Thou hast th' advantage got of many a score

That enter at the open door."——

What an unfounded calumny then must it have been on the part of the Romans, to declare these "Roussins dé Arcadie" (as La Fontaine calls them) so deficient in their aural faculties, that "to talk to a deaf ass" was proverbial for "to labour in vain!"—Perhaps it was under the same delusion that, as Goldsmith says,—

"John Trott was desired by two witty peers,

To tell them the reason why asses had ears."John owns his ignorance of the subject, and facetiously exclaims—

"Howe'er, from this time, I shall ne'er see your graces,

As I hope to be saved! without thinking on asses!"Which joke, by the bye, the author of "Waverley" has deigned to make free with, and thrust into the mouth of a thick-headed fellow, in the fourth volume of the "Crusaders."

Gesner says he saw one leap through a hoop, and, at the word of command, lie down just as if he were dead.

Mahomet had an excellent creature, half ass and half mule: for if we may take his word for it, the beast carried him from Mecca to Jerusalem in the twinkling of an eye in one step!—"It is only the first step which is difficult," says the French proverb, and here it is undoubtedly right.

Sterne gives us a most affecting account of one which had the misfortune to die. "The ass," the old owner told him, "he was assured loved him. They had been separated three days, during which time the ass had sought him as much as he had sought the ass: and they had scarce either eat or drank till they met." This certainly could not have assisted much to improve the health of the donkey. I cannot better conclude my evidence of his shrewdness and capacity than with an anecdote which many authors combine in declaring:—

"De la peau du lion l'âne s'étant vêtu

Etoit craint partout à la ronde;

Et bien qu'animal sans vertu

Il faisoit trembler tout le monde.

Un petit bout d'oreille, echappé par malheur,

Decouvrit la fourbe et l'erreur.

Martin fit alors son office," &c.La Fontaine.

It is curious to see the same taste and the same peculiarities attached to the same family. As long as the ass was thought to be a lion, he was suffered to go on,—but when he is discovered to be an ass, forth steps Mr. Martin—then the task is his!

Now for the estimation in which they were held.

Shakspeare makes the fairy queen, the lovely Titania, fall in love with a gentleman who sported an ass's head:—

"Methought I was enamour'd of an ass,"

said the lady waking—and she thought right, if love be

All made of fantasy,

"All adoration, duty, and observance."At Rouen, they idolized a donkey in the most ludicrous manner, by dressing him up very gaily in the church, dancing round him, and singing, "eh! eh! eh! father ass! eh! eh! eh! father ass!" which, however flattering to him, was really no compliment to themselves.

The ass on which Silenus rode, when he did good service to Jove, and the other divinities, was transported up into the celestial regions. Apion affirms, that when Antiochus spoiled the temple at Jerusalem a golden ass's head was found, which the Jews used to worship.—To this Josephus replies with just indignation, and argues how could they adore the image of that, which, "when it does not perform what we impose upon it, we beat with a great many stripes!" Poor beasts! they must be getting used to hard usage by this time! The wild ass was a very favourite creature for hunting, as we learn from Martial (13 Lib. 100 Ep.); and Virgil sings—

"Sæpè etiam cursu timidos agitabis onagros."

Its flesh was esteemed a dainty. Xenophon, in the first book of the "Anabasis," compares it to venison; and Bingley says, it is eaten to this day by the Tartars: but what is more curious, Mæcenas, who was a sensible man in other respects, preferred, according to Pliny, the meat of the foal of the tame donkey! "de gustibus non disputandum" indeed! With its milk Poppœa composed a sort of paste with which she bedaubed her face, for the purpose of making it fair; as we are told by Pliny (Lib. 11. 41.) and Juvenal (Sat. 2. 107): and in their unadulterated milk she used frequently to bathe for the same purpose (Dio. 62. 28.):

"Propter quod secum comites educit asellas

Exul Hyperboreum si dimittatur ad axem."Juv. 6. 468.

And in both respects she was imitated by many of the Roman ladies. Of its efficacy to persons of delicate habits there can be no doubt, and Dr. Wolcott only called it in question (when recommended by Dr. Geach,) for the purpose of making the following excellent epigram:—

"And, doctor, do you really think

That ass's milk I ought to drink?

'Twould quite remove my cough, you say,

And drive my old complaints away.—

It cured yourself—I grant it true—

But then—'twas mother's milk to you?"And lastly, even when dead, his utility is not ended; for, as we read in Plutarch (Vita Cleomenis) the philosopher affirmed, that "from the dead bodies of asses, beetles were produced!"

TIM TIMS.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Devil's Bit Scabious. Scabiosa Succisa.

Dedicated to St. Lucy.