September 7.

St. Cloud, A. D. 560. St. Regina, or St. Reine, A. D. 251. St. Evurtius, A. D. 340. St. Grimonia, or Germana. St. Madelberte, A. D. 705. Sts. Alchmund and Tilberht, Bps. of Hexham, A. D. 780 and 789. St. Eunan, first Bp. of Raphoe.

St. Enurchus, or Evurtius.This saint is in the church of England calendar, and therefore in the English almanacs, but on what ground it is difficult to conjecture; for Butler himself merely mentions him as a bishop of Orleans, who lived in the reign of Constantine, and died about 340:—he adds, that "his name is famous, but his history of no authority."

"Fine Feathers make fine Birds."

The subjoined letter, dated the 7th of September, 1825, appears in The Times newspaper of the following day:—

To the Editor of the Times.

Sir,—I consider it necessary to inform the public, through your paper, that there is a fellow going about the town, (dressed like a painter,) imposing upon the unwary, by selling them painted birds, for foreign ones. He entered my house on Monday last, and after some simple conversation with the customers in the room, he introduced the topic of his birds, which he had in a paper bag, stating that he had been at work in a gentleman's family at the west end of the town, and the gentleman being on the point of leaving England for a foreign country, he made him a present of them; "but," says he, "I'm as bad as himself, for I'm going down to Canterbury to-morrow morning myself, to work, and they being of no use to me, I shall take them down to Whitechapel and sell them for what I can get." Taking one out of the bag, he described it as a Virginia Nightingale, which sung four distinct notes or voices: the colour certainly was most beautiful; its head and neck was a bright vermilion, the back betwixt the wings a blue, the lower part to the tail a bright yellow, the wings red and yellow; the tail itself was a compound mixture of the above colours, the belly a clear green—he said it was well worth a sovereign to any gentleman. However, after a good deal of lying, bidding and argument, one of the party offered five shillings, which he at last took; and disposing of the others much in the same way, he quickly decamped. In the course of an hour after, a barber, a knowing hand in the bird way, who lives in the neighbourhood, came in, and taking a little water, with his white apron he transferred the variegated colours of the nightingale to the white flag of his profession. The deception was visible—the swindler had fled—and the poor hedge-sparrow had his unfortunate head severed from his body, for being forced to personate a nightingale.

A LICENSED VICTUALLER.

Upper Thames-street.By the preceding letter in The Times, a great number of persons were first acquainted with a fraud frequently practised. As a useful and amusing communication it has a place here. It may, however, be as well to correct an error which the intelligent "Licensed Victualler" falls into by venturing beyond a plain account, to indulge in figurative expression. It is not doubted that his "barber, a knowing hand in the bird way," wore "a white apron;" but when the "Licensed Victualler" calls the barber's white apron "the white flag of his profession," he errs; a white apron may be the "flag" of the "Licensed Victuraller's profession," but it is not the barber's "flag."

The Barber.

Randle Holme, an indisputable authority, in his great work on "Heraldry," figures a barber as above. "He beareth argent," says Holme; "a barber bare-headed with a pair of cisers in his right hand, and a comb in his left, clothed in russet, his apron checque of the first, and azure; a barber is always known by his checque party-coloured apron, therefore it needs not mentioning." Holme emphatically adds, "neither can be termed a barber, (or poler, or shaver,) as anciently they were called, till his apron be about him;" that is to say, "his checque party-coloured apron." This, and this only, is the "flag of his profession."

Holme derives the denomination barber from barba, a beard, and describes him as a cutter of hair; he was also anciently termed a poller, because in former times to poll was to cut the hair: to trim was to cut the beard, after shaving, into form and order.

The intrument-case of a barber, and the instruments in their several divisions, are particularly described by Holme. It contained his looking-glass, a set of horn combs with teeth on one side and wide, "for the combing and readying of long, thick, and stony heads of hair, and such like perriwigs;" a set of box combs, a set of ivory combs with fine teeth on both sides, an ivory beard-comb, a beard-iron called the forceps, being a curling iron for the beard, a set of razors, tweezers with an earpick, a rasp to file the point of a tooth, a hone for his razors, a bottle of sweet oil for his hone, a powder box with sweet powder, a puff to powder the hair, a four square bottle with a screwed head for sweet water, wash balls and sweet balls, caps for the head to keep the hair up, trimming cloths to put before a man, and napkins to put about his neck, and dry his hands and face with. After he was shaved and barbed, the barber was to hold him the glass, that he might see "his new-made face," and instruct the barber where it was amiss: the barber was then to "take off the linens, brush his clothes, present him with his hat, and, according to his hire, make a bow, with 'your humble servant, sir.'"

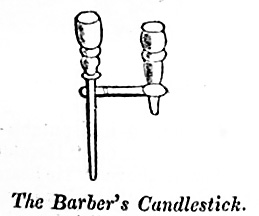

The same author thus figures

The Barber's Candlestick.

He describes it to be "a wooden turned stick, having a socket in the streight peece, and another in the cross or over-thwart peece; this he sticketh in his apron strings on his left side or breast when he useth to trim by candlelight."

Without going into every particular concerning the utensils and art of "Barbering and Shaving," some may be deemed curious, and therefore worthy of notice. It is to be observed, however, that they are from Randle Holme, who wrote in 1688, and relate to barbers of former days.

Barber's Basin.

The barber's washing or trimming-basin had a circle in the brim to compass a man's throat, and a place like a little dish to put the ball in after lathering. Holme says, that "such a like bason as this, valiant Don Quixote took from a bloody enchanting barber, which he took to be a golden head-piece."

The barber's basin is very ancient; it is mentioned by Ezekiel the prophet. In the middle age it was of bright copper.*[1]

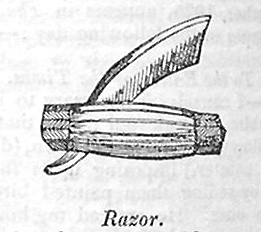

Razor.

This is a figure of the old razor of a superior kind, tipped with silver; "that is," says Holme, "silver plates engraven are fixed upon each end of the haft, to make the same look more gent and rich." The old man, being fidgetted by this ornament, declares, "it is very oft done by yong proud artists who adorne their instruments with silver shrines, more then seting themselves forth by the glory that attends their art, or praise obtained by skill." Before English manufactures excelled in cutlery, razors were imported from Palermo.[2]† Razors are mentioned by Homer.

Barber's Chafer.

"This is a small chafer which they use to carry about with them, when they make any progress to trim or barb gentiles at a distance, to carry their sweet water (or countreyman's broth) in; the round handle at the mouth of the chafer is to fall down as soon as their hand leaves it;" so says Holme. Mr. J. T. Smith remarks, that "the flying barber is a character now no more to be seen in London, though he still remains in some of our country villages; he was provided with a napkin, soap, and pewter bason, the form of which may be seen in many of the illustrative prints of Don Quixote." The same writer speaks of the barber's chafer as being—"A deep leaden vessel, something like a chocolate pot, with a large ring, or handle, at the top; this pot held about a quart of water boiling hot, and thus equipped, he flew about to his customers." These chafers are no longer made in London; the last mould which produced them was sold in New-street, Shoe-lane, at the sale of Mr. Richard Joseph's moulds for pewter utensils, in January, 1815: it was of brass and broken up for metal.*[3]

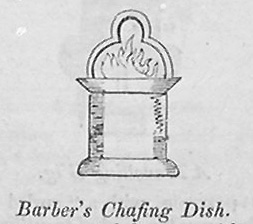

Barber's Chafing Dish.

This was a metal firepot, with a turning handle, and much used during winter, especially in shops without fire-places. It was carried by the handle from place to place, but generally set under a brass or copper basin with a flat broad bottom, whereon if linen cloths were rubbed or let remain, they in a little time became hot or warm for the barber's use.

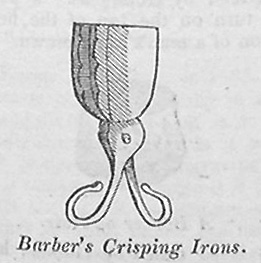

Barber's Crisping Irons.

This is their ancient shape. "In former times these were much used to curl the side locks of a man's head, but now (in 1688) wholly cast aside as useless; it openeth and shutteth like the forceps, only the ends are broad and square, being cut within the mouth with teeth curled and crisped, one tooth striking within another."

Scissors.

Hair-scissors were long and broad in the blades, and rounded towards the points which were sharp.

Beard-scissors had short blades and long handles.

The barber's scissors differed in these respects from others; for instance, the tailor's scissors differed from both by reason of their smallness, some of them having one ring for the thumb only to fit it, while the contrary ring or bow was large enough to admit two or three fingers.

Beards.

Pick-a-devant Beard.

"A full face with a sharp-pointed beard is termed, in blazon, a man's face with a pick-a-devant (or sharp pointed,) beard." Mr. Archdeacon Nares's "Glossary" contains several passages in corroboration of Holme's description of this beard.

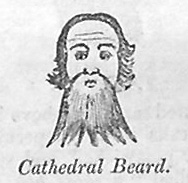

Cathedral Beard.

This Holme calls "the broad or cathedral beard, because bishops and grave men of the church anciently did wear such beards." Besides this, and the pick-a-devant, he says there are several sorts and fashions of beards, viz. "the British beard hath long mochedoes, (mustachios) on the higher lip, hanging down either side the chin, all the rest of the face being bare:—the forked beard is a broad beard ending in two points:—the mouse-eaten beard, when the beard groweth scatteringly, not together, but here a tuft and there a tuft," &c.

Guillaume Duprat, bishop of Clermont, who assisted at the council of Trent, and built the college of the Jesuits at Paris, had the finest beard that ever was seen. It was too fine a beard for a bishop, and the canons of his cathedral, in full chapter assembled, came to the barbarous resolution of shaving him. Accordingly, when next he came to the choir, the dean, the prevot, and the chantre approached with scissors and razors, soap, basin and warm water. He took to his heels at the sight, and escaped to his castle of Beauregard, about two leagues from Clermont, where he fell sick vor vexation, and died.*[4]

Ancient monuments represent the Greek heroes to have worn short curled beards. Among the Romans, after the year 454, C. B., philosophers alone constantly wore a beard; the beard of their military men was short and frizzed. The first emperors with a long and thick beard were Hadrian, who wore it to hide his wounds, and Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius, who wore it as philosophers: a thick beard was afterwards considered an appendage that obtained for the emperors veneration from the people. [5]†

Wigs.

A Peruke.

It is figured as seen above by Holme, who also calls it in his peculiar orthography a "perawicke," and says it was likewise called "a short bob, a head of hair—a wig that hath short locks and a hairy crown." He describes it with some feeling. "This is a counterfeit hair which men wear instead of their own; a thing much used in our days by the generality of men; contrary to our forefathers who got estates, loved their wives, and wore their own hair; but," says he, "in these days (1688) there is no such things!"

He further gives the following as

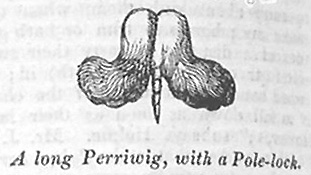

A long Perriwig, with a Pole-lock.

This he puts forth as being "by artists called a long-curled-wig, with a suffloplin, or with a dildo, or pole-lock;" and he affirms, that "this is the sign or cognizance of the perawick-maker."

That the peruke was anciently a barber's sign, is verified by a very rare, and perhaps an unique engraving of St. Paul's cathedral when building, with the scaffolding poles and boards up. This print, in the possession of the editor of the Every-Day Book, represents a barber's shop on the north-side of St. Paul's churchyard, with the barber's pole out at the door, and a swinging sign projecting from each side of the house, a peruke being painted on each.

A Travelling Wig.

This peruque, with a "curled foretop and bobs," was "a kind of travelling wig," having the side or bottom locks turned up into bobs or knots tied up with ribbons." Holme further calls it "a campaign-wig," and says, "it hath knots or bobs, or a dildo, on each side, with a curled forehead."

A Grafted Wig

is described by Holme as "a perawick with a turn on the top of the head, in imitation of a man's hairy crown."

A Border of Hair.

This is so called by Holme; he also calls it "a peruque, with the crown or top cut off; some term it the border of a peruque:" he adds, that "women usually wear such borders, which they call curls or locks when they hang over their ears." He further says, they were called "taures when set in curls on the forehead," and "merkins" when the curls were worn lower, or at the sides of the face.

A Bull-head.

"Some," says Holme, "term this curled forehead a bull-head, from the French word taure, because taure is a bull; it was the fashion of women to wear bull-heads, or bull-like foreheads, anno 1674, and about that time: this is the coat (of arms) of Taurell, a French monsieur, or seigneur."

Curls on Wires.

According to our chief authority, Holme, a female thus "quoiffed," with "a pair of locks and curls," was in "great fashion, about the year 1670." He adds, that "they are false locks, set on wyres, to make them stand at a distance from the head; as the fardingales made their clothes stand out (from the hips downwards) in queen Elizabeth's reign."

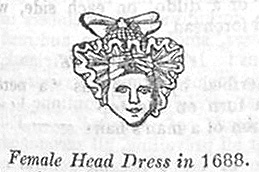

Female Head Dress in 1688.

There is a little difficulty in naming this head dress; for Holme is so diffuse and indignant that he gives it no term though he describes the engraving. The figure is remarkable because it is in many respects similar to the manner wherein the ladies of 1825 adjust the head. It will be remembered that Holme was a herald, and though his descriptions have not hitherto been here related in his armorial language, he always sets them out so, in his "storehouse of armory and blazon." It may be amusing to conclude these extracts from him with his description of this figure in his own words: thus than the old "deputy for the kings of arms" describes it:—

"He beareth argent a woman's face; her forehead adorned with a knot of diverse coloured ribbons; the head with a ruffle quoif, set in corners, and the like ribbons behind the head. This," says Holme, "is a fashion-monger's head, tricked and trimed up [sic], according to the mode of these times, wherein I am writing of it; and, in my judgment, were a fit coat for such seamsters as are skilled in inventions. But" (he angrily breaks forth,) "what do I talk of arms to such, by reason they will be shortly old, and therefore not to be endured by them, whose brains are always upon new devises and inventions! But all are brought again from the old; for there is no new thing under the sun; for what is now, hath been formerly!"

In the great dining-room at Lambeth-palace, there are portraits of all the archbishops, from Laud to the present time. In these we may observe the gradual change of the clerical dress, in the article of wigs. Archbishop Tillotson was the first prelate who wore a wig, which then was not unlike the natural hair, and worn without powder.*[6]

It is related of a barber in Paris, that, to establish the utility of his bag-wigs, he caused the history of Absalom to be painted over his door; and that one of the profession, at a town in Northamptonshire, used this inscription, "Absalom, hadst thou worn a perriwig, thou hadst not been hanged."[7] It is somewhere told of another that he ingeniously versified his brother peruke-maker's inscription, under a sign which represented the death of Absalom and David weeping; he wrote up thus:—

"Oh, Absalom! Oh, Absalom!

Oh, Absalom! my son,

If thou hadst worn a perriwig,

Thou hadst not been undone!"

The well-known, light, flaxen wig of Townsend, the well-known police-officer, is celebrated in a song beginning thus:—

Townsend's Wig.

Tune—"Nancy Dawson."

Of all the wigs in Brighton town,

The black, the grey, the red, the brown,

So firmly glued upon the crown,

There's none like Johnny Townsend's:

It's silken hair and flaxen hue,

(It is a scratch, and not a queue,)

Whene'er it pops upon the view,

Is known for Johnny Townsend's!

Wigs were worn by the romans when bald; those of the Roman ladies were fastened upon a caul of goat-skin. Periwigs commenced with their emperors; they were awkwardly made of hair, painted and glued together.

False hair was always in use, though more from defect than fashion; but the year 1529 is deemed the epoch of the introduction of long perriwigs into France; yet it is certain that ladies tetes were in use here a century before. Mr. Fosbroke, from whose "Encyclopædia of Antiquities" these particulars are derived, says, "that strange deformity, the judge's wig, first appears as a general genteel fashion in the seventeenth century." Towards the close of that century, men of fashion combed their wigs at public places, as an act of gallantry, with very large ivory or tortoiseshell combs, which they carried in their pockets as constantly as their snuff-boxes. At court, in the mall of St. James's-park, and in the boxes of the theatre, gentlemen conversed and combed their perukes.

Hair.

Horace Walpole relates that when the countess of Suffolk married Mr. Howard, they were both so poor, that they took a resolution of going to Hanover before the death of queen Anne, in order to pay their court to the future royal family. Having some friends to dinner, and being disappointed of a full remittance, she was forced to sell her hair to furnish the entertainment. Long wigs were then in fashion, and the countess's hair being fine, long, and fair, produced here twenty pounds.

A fashion of wearing the hair gave rise to a college term at Cambridge, which is thus mentioned and explained in a dictionary of common parlance at that university:—

"APOLLO. One whose hair is loose and flowing;

Unfrizzled, unanointed, and untied;

No powder seen.——"His royal highness prince William of Gloucester was an Apollo during the whole of his residence at the university of Cambridge! The strange fluctuation of fashions has often afforded a theme for amusing disquisition. 'I can remember,' says the pious archbishop Tillotson, in one of his sermons, discoursing on this head, viz. of hair! 'since the wearing the hair below the ears was looked upon as a sin of the first magnitude; and when ministers generally, whatever their text was, did either find, or make occasion to reprove the great sin of long hair; and if they saw any one in the congregation guilty in that kind, they would point him out particularly, and let fly at him with great zeal.' And we can remember since, the wearing the hair cropt, i.e. above the ears, was looked upon, though not as a 'sin,' yet as a very vulgar and raffish sort of thing; and when the doers of newspapers exhausted all their wit in endeavouring to rally the new-raised corps of crops, regardless of the noble duke who headed them; and, when the rude, rank-scented rabble, if they saw any one in the streets, whether time, or the tonsor, had thinned his flowing hair, would point him out particularly, and 'let fly at him,' as the archbishop says, till not a shaft of ridicule remained! The tax upon hair powder has now, however, produced all over the country very plentiful crops. Among the Curiosa Cantabrigiensia, it may be recorded, that our 'most religious and gracious king,' as he was called in the liturgy, Charles the Second, who, as his worthy friend, the earl of Rochester, remarked,

never said a foolish thing,

Nor ever did a wise one,'—sent a letter to the university of Cambridge, forbidding the members to wear perriwigs, smoke tobacco, and read their sermons! It is needless to remark, that tobacco has not yet made its exit in fumo, and that perriwigs still continue to adorn 'the heads of houses!' —— Till the present all prevailing, all accommodating fashion of crops became general at the university, no young man presumed to dine in hall till he had previously received a handsome trimming from the hair-dresser. An inimitable imitation of 'The Bard' of Gray, is ascribed to the pen of the honourable Thomas (the late lord) Erskine, when a student at Cambridge, Mr. E. having been disappointed of the attendance of his college barber, was compelled to forego his commons in hall! An odd thought came into his head. In revenge, he determined to give his hair-dresser a good dressing; so he sat down, and began as follows:—

" 'Ruin seize thee, scoundrel Coe,

Confusion on thy frizzing wait;

Hadst thou the only comb below,

Thou never more shouldst touch my pate." 'Club, nor queue, nor twisted tail,

Nor e'en thy chatt'ring, barber, shall avail

To save thy horse-whipped back from daily fears

From Cantab's curse, from Cantab's tears.' "

The editor of the "Gradus ad Cantabrigiam" regrets that he has not room for the whole of the ode.

An Ancient Barber.

There is a curious print from Heemskerck, of a barber of old times labouring in his vocation: it shows his room or shop. An old woman is making square pancakes at the fire-place, before which an overfed man sits on a chair sleeping: there is a fat toping friar seated by the chimney corner, with his fingers on the crossed hands of a demure looking nun by his side, and he holds up a liquor-measure to denote its emptiness: a nun-like female behind, blows a pair of bellows over her shoulder, and seems dancing to a tune played on the guitar or cittern, by a humorous looking fellow who is standing up: another nun-like female sounds a gridiron with a pair of tongs, while another friar blows an instrument through a window. These persons are perhaps sojourning there as pilgrims, for there is a print hung against the wall representing an owl in a pilgrim's habit on his journey. In this room the barber's bleeding basin is hung up, and his razor is on the mantel ledge: the barber himself is washing the chin of an aged fool, whom, from the hair lying on the ground, it appears he has just polled. A dog on his hind legs is in a fool's habit, probably to intimate that the fool is under the hands of the barber preparatory to his fraternizing with the friars and their dames. The print is altogether exceedingly humorous, and illustrative of manners: so much of it as immediately concerns the barber is given in the present engraving from it.

Mr. Leigh Hunt, in "The Indicator," opposes female indifference to the hair. He says, "Ladies, always delightful, and not the least so in their undress, are apt to deprive themselves of some of the best morning beams by appearing with their hair in papers. We give notice, that essayists, and of course all people of taste, prefer a cap, if there must be any thing; but hair, a million times over. To see grapes in paper-bags is bad enough; but the rich locks of a lady in papers, the roots of the hair twisted up like a drummer's, and the forehead staring bald instead of being gracefully tendrilled and shadowed!—it is a capital offence,—a defiance to the love and admiration of the other sex,—a provocative to a paper war: and we here accordingly declare the said war on paper, not having any ladies at hand to carry it at once into their headquarters. We must allow at the same time, that they are very shy of being seen in this condition, knowing well enough, how much of their strength, like Sampson's, lies in that gifted ornament. We have known a whole parlour of them fluttered off, like a dove-cote, at the sight of a friend coming up the garden."

Of the barber's art, as it was practised formerly, Mr. Archdeacon Nares gives a curious sample from Lyly, an old dramatist, one of whose characters being a barber, says, "thou knowest I have taught thee the knacking of the hands, the tickling on a man's haires, like the tuning of a citterne. I instructed thee in the phrases of our eloquent occupation, as, how, sir, will you be trimmed? will you have your beard like a spade or a bodkin? a pent-hous on your upper lip, or an ally on your chin? a low curle on your head like a bull, or dangling locke like a spaniel? your mustachoes sharpe at the ends, like shomakers' aules, or hanging downe to your mouth like goates flakes? your love-lockes wreathed with a silken twist, or shaggie to fall on your shoulders?"

Barbers' shops were anciently places of great resort, and the practices observed there were consequently very often the subject of allusions. The cittern, or lute, which hung up for the diversion of the customers, is the foundation of a proverb.*[8] The cittern resembled the guitar. In Burton's "Winter Evening Entertainments," published in 1687, with several wood-cuts, there is a representation of a barber's shop, where the person waiting his turn is playing on a lute.† [9]

The peculiar mode of snapping the fingers, as a high qualification in a barber, is mentioned by Green, another early writer. "Let not the barber be forgotten: and look that he be an excellent fellow, and one that can snap his fingers with dexterity." Morose, one of Ben Jonson's characters in his "Silent Woman," is a detester of noise, and particularly values a barber who was silent, and did not snap his fingers. "The fellow trims him silently, and hath not the knack with his shears or his fingers: and that continency in a barber he thinks so eminent a virtue, as it has made him chief of his counsel." ‡[10]

This obsolete practice with barbers is noticed in Stubbe's "Anatomy of Abuses." "When they come to washing," says Stubbe, "oh! how gingerly they behave themselves therein. For then shall your mouth be bossed with the lather, or some that rinseth of the balles, (for they have their sweete balles wherewith all they use to washe,) your eyes closed must be anointed therewith also. Then snap go the fingers, ful bravely, Got wot. Thus this tragedy ended, comes me warme clothes to wipe and dry him withall; next, the eares must be picked, and closed together againe artificially, forsooth," &c. This citation is given by a correspondent to the "Gentleman's Magazine," who adds to it his own observations:—"I am old enough," he says, "to remember when the operation of shaving, in this kingdom, was almost exclusively performed by the barbers: what I speak of is some three-score years ago, at which time gentlemen-shavers were unknown. Expedition was then a prime quality in a barber, who smeared the lather over his customers' faces with his hand; for the delicate refinement of the brush had not been introduced. The lathering of the beard being finished, the operator threw off the lather adhering to his hand, by a peculiar jerk of the arm, which caused the joints of the fingers to crack, this being a more expeditious mode of clearing the hand than using a towel for that purpose; and the more audible the crack, the higher the shaver stood in his own opinion, and in that of his fraternity. This then, I presume, is the custom alluded to by Stubbe."

Mr. J. T. Smith says, "The entertaining and venerable Mr. Thomas Batrich, barber, of Drury-lane, informs me, that before the year 1756, it was a general custom to lather with the hand; but that the French barbers, much about that time, brought in the brush. He also says, that "A good lather is half the shave," is a very old remark among the trade.

In a newspaper report of some proceedings at a police office, in September, 1825, a person deposing against the prisoner, used the phrase "as common as a barber's chair;" this is a very old saying. One of Shakspeare's clowns speaks of "a barber's chair, that fits all," by way of metaphor; and Rabelais shows that it might be applied to any thing in very common use.*[11]

The Barber's Pole is still a sign in country towns, and in many of the villages near London. It was stated by lord Thurlow in the house of peers, on the 17th of July, 1797, when he opposed the surgeons' incorporation bill that, "By a statute still in force, the barbers and surgeons were each to use a pole. The barbers were to have theirs blue and white, striped, with no other appendage; but the surgeons, which was the same in other respects, was likewise to have a gallipot and a red rag, to denote the particular nature of their vocation."

The origin of the barber's pole is to be traced to the period when the barbers were also surgeons, and practised phlebotomy. To assist this operation, it being necessary for the patient to grasp a staff, a stick or a pole was always kept by the barber-surgeon, together with the fillet or bandaging he used for tying the patient's arm. When the pole was not in use the tape was tied to it, that they might be both together when wanted. On a person coming in to be bled the tape was disengaged from the pole, and bound round the arm, and the pole was put into the person's hand: after it was done with, the tape was again tied on the pole, and in this state, pole and tape were often hung at the door, for a sign or notice to passengers that they might there be bled: doubtless the competition for custom was great, because as our ancestors were great admirers of bleeding, they demanded the operation frequently. At length instead of hanging out the indentical pole used in the operation, a pole was painted with stripes round it, in imitation of the real pole and its bandagings, and thus came the sign.

That the use of the pole in bleeding was very ancient, appears from an illumination in a missal of the time of Edward I., wherein the usage is represented. Also in "Comenii Orbis pietus," there is an engraving of the like practice. "Such a staff," says Brand, who mentions these graphic illustrations, "is to this very day put into the hand of patients undergoing phlebotomy by every village practitioner."

The News Sunday-paper of August 4, 1816, says, that a person in Alston, who for some years followed the trade of a barber, recently opened a spirit-shop, when to the no small admiration and amusement of his acquaintance, he hoisted over his door the following lines:—

Rove not from pole to pole, but here turn in,

Where naught exceeds the shaving, but the gin.

The south corner shop of Hosier-lane, Smithfield, is noticed by Mr. J. T. Smith as having been "occupied by a barber whose name was Catch-pole; at least so it was written over the door: he was a whimsical fellow; and would, perhaps because he lived in Smithfield, show to his customers a short bladed instrument, as the dagger with which Walworth killed Wat Tyler." To this may be added, a remark not expressed by Mr. Smith, that Catch-pole had a barber's pole for many years on the outside of his door.*[12]

Catch-pole's manœuvre to catch customers, and get his shop talked about, was very successful. It is observed in the "Spectator," that—"The art of managing mankind is only to make them stare a little, to keep up their astonishment, to let nothing be familiar to them, but ever to have something in your sleeve, in which they must think you are deeper than they are." The writer of the remark exemplifies it by this story:—"There is an ingenious fellow, a barber of my acquaintance, who, besides his broken fiddle and a dryed sea-monster, has a twine-cord, strained with two nails at each end, over his window, and the words, rainy, dry, wet, and so forth, written to denote the weather according to the rising or falling of the cord. We very great scholars are not apt to wonder at this: but I observed a very honest fellow, a chance customer, who sat in the chair before me to be shaved, fix his eye upon this miraculous performance during the operation upon his chin and face. When those, and his head also, were cleared of all incumbrances and excrescences, he looked at the fish, then at the fiddle, still grubbing in his pockets, and casting his eye again at the twine, and the words writ on each side; then altered his mind as to farthings, and gave my friend a silver sixpence. The business, as I said, is to keep up the amazement: and if my friend had had only the skeleton and kitt, he must have been contented with a less payment."

It was customary with barbers to have their shops lighted by candles in brass chandeliers of three, four, and six branches. Mr. Smith noticing their disuse says, "Mr. Batrich has two suspended from his ceiling; he has also a set of bells fixed against the wall, which he has had for these forty years. These are called by the common people Whittington's Bells. In his early days, about eighty years back, when the newspapers were only a penny a-piece, they were taken in by the barbers for the customers to read during their waiting time. This custom is handed to us by the late E. Heemskerck, in an etching by Toms, of a barber's shop, composed of monkies, at the foot of which are the following lines:—

"A barber's shop adorn'd we see,

With monsters, news, and poverty;

Whilst some are shaving, others bled,

And those that wait the papers read;

The master full of wigg, or tory,

Combs out your wig, and tells a story."

Mr. Smith's inquiries concerning barbers have been extensive and curious. He says, "On one occasion, that I might indulge the humour of being shaved by a woman, I repaired to the Seven Dials, where, in Great St. Andrew's-street, a slender female performed the operation, whilst her husband, a strapping soldier in the Horse-guards, sat smoking his pipe. There was a famous woman in Swallow-street, who shaved; and I recollect a black woman in Butcher-row, a street formerly standing by the side of St. Clement's church, near Temple-bar, who is said to have shaved with ease and dexterity." His friend Mr. Batrich informed him that he had read of "the five barberesses of Drury-lane, who shamefully mal-treated a woman in the reign of Charles II." Mr. Batrich died while Mr. Smith's "Ancient Topography of London," was passing through the press.

The "Glasgow Chronicle," about the year 1817, notices the sudden death, in Calton, of Mr. John Falconer, hairdresser, in Kirk-street. While in the act of shaving a man, he staggered, and was falling, when he was placed on a chair, and expired in five minutes. His shop was the arena of all local discussion and was therefore denominated the Calton coffeeroom. His father and he had been in the trade for upwards of half a century. His father was the first who reduced the price of shaving to a halfpenny; and when his brethren in the town wished him again to raise it, he replied, "Charge a penny! Jock and me are just considering about lowering it to a farthing." He would never take more than a halfpenny though it was offered him; and being very skilful at his business, and of a frank jocular turn, he had a large share of public favour, and was enabled even at this low rate to gather money and build houses. He died about sixteen years before his son, who carried on the business. He often said others wrought for need, but he did it for pleasure or recreation, and never was so happy as when he was improving the countenances of the lieges. He was generally allowed to be at the top of his profession. Some old men whom he and his father had shaved for fifty years, boasted that they were never touched by another: one very old customer regularly came for many a year to his shop every Saturday night from the western extremity of the town. His shop was furnished with two dozen of antique chairs, as many pictures, and a musical clock, and for a long time he had a good library of books, but they at length nearly wholly disappeared, and he took up to his house the few that remained as his own share. At two different times, when trade was dull, he gave his tenants a jubilee on the term day, and presented their discharges without receiving a farthing. He left behind him property worth between 2,000l. and 3000l.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Golden Starwort. Aster Solidaginoides.

Dedicated to St. Cloud.