August 25.

St. Lewis, king of France, A. D. 1270, St. Gregory, Administrator of the diocess of Utrecht, A. D. 776. St. Ebba. in English, St. Tabbs, A. D. 683.

PRINTERS.

An exact old writer† ‡[1] says of printers at this season of the year, that "It is customary for all journeymen to make every year, new paper windows about Bartholomew-tide, at which time the master printer makes them a feast called a way-goose, to which is invited the corrector, founder, smith, ink-maker, &c. who all open their purses and give to the workmen to spend in the tavern or ale-house after the feast. From which time they begin to work by candle light."

Paper windows are no more: a well regulated printing-office is as well glazed and as light as a dwelling-house. It is curious however to note, that it appears the windows of an office were formerly papered; probably in the same way that we see them in some carpenters' workshops with oiled paper. The way-goose, however, is still maintained, and these feasts of London printing-houses are usually held at some tavern in the environs.

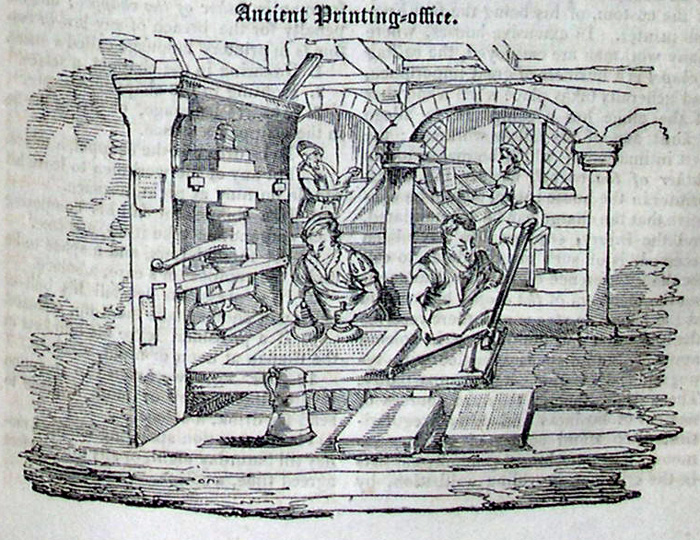

In "The Doome warning all men to the Judgment, by Stephen Batman, 1581," a black letter quarto volume, it is set down among "the straunge prodigies hapned in the worlde, with divers figures of revelations tending to mannes stayed conversion towardes God," whereof the work is composed, that in 1450, "The noble science of printing was aboute thys time founde in Germany at Magunce, (a famous citie in Germanie called Ments,) by Cuthembergers, a knight, or rather John Faustus, as sayeth doctor Cooper, in his Chronicle; one Conradus, an Almaine broughte it into Rome, William Caxton of London, mercer, broughte it into England, about 1471; In Henrie the sixth, the seaven and thirtith of his raign, in Westminster was the first printing." John Guttemberg, sen. is affirmed to have produced the first printed book, in 1442, although John Guttemberg, jun. is the commonly reputed inventor of the art. John Faust, or Fust, was its promoter, and Peter Schoeffer its improver. It started to perfection almost with its invention; yet, although the labours of the old printer have never been outrivalled, their presses have; for the information and amusement of some readers, a sketch is subjoined of one from a wood-cut in Batman's book.

Ancient Printing-office.

In this old print we see the compositor seated at his work, the reader engaged with his copy or proof, and the pressmen at their labours. It exhibits the form of the early press better, perhaps, than any other engraving that has been produced for that purpose; and it is to be noted, as a "custom of the chapel," that papers are stuck on it, as we still see practised by modern pressmen. Note, too, the ample flagon, a vessel doubtless in use ad libitum, by that beer-drinking people with whom printing originated, and therefore not forgotten in their printing-houses; it is wisely restricted here, by the interest of employers, and the growing sense of propriety in press-men, who are becoming as respectable and intelligent a class of "operatives" as they were, within recollection, degraded and sottish.

The Chapel.

"Every printing-house," says Randle Holme, "is termed a chappel." Mr. John M'Creery in one of the notes to "The Press," an elegant poem, of which he is the author, and which he beautifully printed, with elaborate engravings on wood, as a specimen of his typography, says, that "The title of chapel to the internal regulations of a printing-house originated in Caxton's exercising the profession in one of the chapels in Westminster Abbey; and may be considered as an additional proof, from the antiquity of the custom, of his being the first English printer. In extensive houses, where many workmen are employed, the calling a chapel is a business of great importance, and generally takes place when a member of the office has a complaint to allege against any of his fellow workmen; the first intimation of which he makes to the father of the chapel, usually the oldest printer in the house: who, should he conceive that the charge can be substantiated, and the injury, supposed to have been received, is of such magnitude as to call for the interference of the law, summonses the members of the chapel before him at the imposing stone, and there receives the allegation and the defence, in solemn assembly, and dispenses justice with typographical rigour and impartiality. These trials, though they are sources of neglect of business and other irregularities, often afford scenes of genuine humour. The punishment generally consists in the criminal providing a libation, by which the offending workmen may wash away the stain that his misconduct has laid upon the body at large. Should the plaintiff not be able to substantiate his charge, the fine then falls upon himself for having maliciously arraigned his companion; a mode of practice which is marked with the features of sound policy, as it never loses sight of the good of the chapel."

Returning to Randle Holme once more, we find the "good of the chappel" consists of "forfeitures and other chappel dues, collected for the good of the chappel, viz. to be spent as the chappel approves." This indefatigable and accurate collector and describer of every thing he could lay his hands on and press into heraldry, has happily preserved the ancient rules of government instituted by the worshipful fraternity of printers. This book is very rare, and this perhaps may have been the reason that the following document essentially connected with the history of printing, has never appeared in one of the many works so entitled.

Customs of the Chappel.

Every printing-house is called a chappel, in which there are these laws and customs, for the well and good government of the chappel, and for the orderly deportment of all its members while in the chappel.

Every workman belonging to it are members of the chappel, and the eldest freeman is father of the chappel; and the penalty for the breach of any law or custom is in printers' language called a solace.

1. Swearing in the chappel, a solace.

2. Fighting in the chappel, a solace.

3. Abusive language, or giving the lie in the chappel, a solace.

4. To be drunk in the chappel, a solace.

5. For any of the workmen to leave his candle burning at night, a solace.

6. If a compositor fall his composing stick and another take it up, a solace.

7. For three letters and a space to lie under the compositor's case, a solace.

8. If a pressman let fall his ball or balls, and another take them up, a solace.

9. If a pressman leave his blankets in the timpan at noon or night, a solace.

10. For any workman to mention joyning their penny or more a piece to send for drink, a solace.

11. To mention spending chappel money till Saturday night, or any other before agreed time, a solace.

12. To play at quadrats, or excite others in the chappel to play for money or drink, a solace.

13. A stranger to come to the king's printing-house, and ask for a ballad, a solace.

14. For a stranger to come to a compositor and inquire if he had news of such a galley at sea, a solace.

15. For any to bring a wisp of hay directed to a pressman, is a solace.

16. To call mettle lead in a founding-house, is a forfeiture.

17. A workman to let fall his mould, a forfeiture.

18. A workman to leave his ladle in the mettle at noon, or at night, a forfeiture.

And the judges of these solaces, or forfeitures, and other controversies in the chappel, or any of its members, was by plurality of votes in the chappel; it being asserted as a maxime, that the chappel cannot err. Now these solaces, or fines, were to be bought off for the good of the chappel, which never exceeded 1s., 6d., 4d., 2d., 1d., ob., according to the nature and quality thereof.

But if the delinquent proved obstinate and will not pay, the workmen takes him by force, and lays him on his belly, over the correcting stone, and holds him there whilest another with a paper board gives him 10l. in a purse, viz., eleven blows on his buttocks, which he lays on according to his own mercy.

Customs for Payments of Money.

Every new workman to pay for his entrance half a crown, which is called his benvenue, till then he is no member, nor enjoys any benefit of chappel money.

Every journeyman that formerly worked at the chappel, and goes away, and afterwards comes again to work, pays but halve a benvenue.

If journeymen smout* [2] one another, they pay half a benvenue.

All journeymen are paid by their master-printer for all church holidays that fall not on a Sunday, whether they work or no, what they can earn every working-day, be it 2, 3, or 4s.

If a journeyman marries, he pays half a crown to the chappel.

When his wife comes to the chappel, she pays 6d., and then all the journeymen joyn their 2d. a piece to make her drink, and to welcome her.

If a journeyman have a son born, he pays 1s., if a daughter 6d.

If a master-printer have a son born, he pays 2s. 6d., if a daughter 1s. 6d.

An apprentice, when he is bound, pays half a crown to the chappel, and when he is made free, another half crown: and if he continues to work journeywork in the same house he pays another, and then is a member of the chappel.

Probably there will many a conference be held at imposing-stones upon the present promulgation of these ancient rules and customs; yet, until a general assembly, there will be difficulty in determining how far they are conformed to, or departed from, by different chapels. Synods have been called on less frivolous occasions, and have issued decrees more "frivolous and vexatious," than the one contemplated.

In a work on the origin and present state of printing, entitled "Typographica, or the Printer's Instructor, by J. Johnson, Printer, 1824, 2 vols.," there is a list of "technical terms made use of by the profession," which Mr. Johnson prefaces by saying, "we have here introduced the whole of the technical terms, that posterity may know the phrases used by the early nursers and improvers of our art." However, they are not "the whole," nor will it detract from the general merit of Mr. Johnson's curious and useful work, nor will he conceive offence, if the Editor of the Every-Day Book adds a few from Holme's "Academy of Armory,["] a rare store-house of "Created Beings, with the terms and instruments used in all trades and arts," and printers are especially distinguished.

Additions to Mr. Johnson's List of Printers' Terms.

Bad Copy. Manuscript sent to be printed, badly or imperfectly written.

Bad Work. Faults by the compositor or pressman.

Broken Letter. The breaking of the orderly succession the letters stood in, either in a line, page, or form; also the mingling of the letters, technically called pie.

Case is Low. Compositors say this when the boxes, or holes of the case, have few letters in them.

Case is full. When no sorts are wanting.

Case stands still. When the compositor is not at his case.

Cassie Paper. Quires made up of torn, wrinkled, stained, or otherwise faulty sheets.

Cassie Quires. The two outside quires of the ream, also called cording quires.

Charge. To fill the sheet with large or heavy pages.

Companions. The two press-men working at one press: the one first named has his choice to pull or beat; the second takes the refuse office.

Comes off. When the letter in the form delivers a good impression, it is said to come off well; if an ill impression, it is said to come off bad.

Dance. When the form is locked up, if, upon its rising from the composing-stone, letters do not rise with it, or any drop out, the form is said to dance.

Distribute. Is to put the letters into their several places in the case after the form is printed off.

Devil. Mr. Johnson merely calls him the errand-boy of a printing-house; but though he has that office, Holme properly says, that he is the boy that takes the sheets from the tympan, as they are printed off. "These boys," adds Holme, "do in a printing-house commonly black and dawb themselves, whence the workmen do jocosely call them devils, and sometimes spirits, and sometimes flies."

Drive out. "When a compositor sets wide," says Mr. Johnson. Whereto Holme adds, if letter be cast thick in the shank it is said to drive out, &c.

Easy Work. Printed, or fairly written, copy, or full of breaks, or a great letter and small form "pleaseth a compositor," and is so called by him.

Empty Press. A press not in work: most commonly every printing-office has one for a proof-press: viz. to make proofs on.

Even Page. The second, fourth, sixth, &c. pages.

Odd Page. The first, third, fifth, &c. pages.

Folio. Is, in printer's language, the two pages of a leaf of any size.

Form rises. When the form is so well locked up in the chase, that in the raising of it up neither a letter nor a space drops out, it is said that the form rises.

Froze out. In winter, when the paper is frozen, and the letter frozen, so as the workmen cannot work, they say they are froze out. [Such accidents never occur in good printing-houses.]

Going up the form. A pressman's phrase when he beats over the first and third rows or columns of the form with his ink balls.

Great bodies. Letter termed "English," and all above that size: small bodies are long primer, and all smaller letter.

Great numbers. Above two thousand printed of one sheet.

Hard work, with compositors, is copy badly written and difficult; [such as they too frequently receive from the Editor of the Every-Day Book, who alters, and interlines, and never makes a fair copy,] hard work, with pressmen, is small letter and a large form.

Hole. A place where private printing is used, viz, the printing of unlicensed books, or other men's copies.

[Observe, that this was in Holme's time; now, licensing is not insisted on, nor could it be enforced; but the printing "other men's copies" is no longer confined to a hole. Invasion of copyright is perpetrated openly, because legal remedies are circuitous, expensive, and easily evaded. So long as the law remains unaltered, and people will buy stolen property, criminals will rob. The pirate's "fence" is the public. The receiver is as bad as the thief: if there were no receivers, there would be no thieves. Let the public look to this.]

Imperfections of books. Odd sheets over the number of books made perfect. They are also, and more generally at this time, called the waste of the book.

M thick. An m quadrat thick.

N thick. An n quadrat thick.

Open matter, or open work. Pages with several breaks, or with white spaces between the paragraphs or sections.

Over-run. Is the getting in of words by putting out so much of the forepart of the line into the line above, or so much of the latter part of the line into the line below, as will make room for the word or words to be inserted: also the derangement and re-arrangement of the whole sheet, in order to get in over-matter. [Young and after-thought writers are apt to occasion much over-running, a process distressing to the compositor, and in the end to the author himself, who has to pay for the extra-labour he occasions.]

Pigeon holes. Whites between words as large, or greater than between line and line. The term is used to scandalize such composition; it is never suffered to remain in good work.

Printing-house. The house wherein printing is carried on; but it is more peculiarly used for the printing implements. Such an one, it is said, hath removed his printing-house; meaning the implements used in his former house.

Revise. A proof sheet taken off after the first or second proof has been corrected. The corrector examines the faults, marked in the last proof sheet, fault by fault, and carefully marks omissions on the revise.

Short page. Having but little printed in it; [or relatively, when shorter than another page of the work.]

Stick-full. The composing-stick filled with so many lines that it can contain no more.

Token. An hour's work for half a press, viz. a single pressman; this consists of five quires. An hour's work for a whole press is a token of ten quires.

Turn for it. Used jocosely in the chapel: when any of the workmen complain of want of money, or any thing else, he shall by another be answered "turn for it," viz. make shift for it.

[This is derived from the term turn for a letter, which is thus:—when a compositor has not letters at hand of the sort he wants while composing, and finds it inconvenient to distribute letter for it, he turns a letter of the same thickness, face downwards, which turned letter he takes out when he can accomodate himself with the right letter, which he places in its stead.]

Thus much has grown out of the notice, that printers formerly papered their windows about "Bartelmy-tide," and more remains behind. But before farther is stated, if chapels, or individuals belonging to them, will have the goodness to communicate any thing to the Editor of the Every-Day Book respecting any old or present laws, or usages, or other matters of interest connected with printing, he will make good use of it. Notices or anecdotes of this kind will be acceptable when authenticated by the name and address of the contributor. If there are any who doubt the importance of printing, they may be reminded that old Holme, a man seldom moved to praise any thing but for its use in heraldry, says, that "it is now disputed whether typography and architecture may not be accounted Liberal Sciences, being so famous Arts!" Seriously, however, communications respecting printing are earnestly desired.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Perennial Sunflower. Helianthus multiflorus.

Dedicated to St. Lewis.