June 21.

St. Aloysius, or Lewis Gonzaga, A. D. 1591. St. Ralph, Abp. of Bourges, A. D. 866. St. Meen, in Latin, Mevennus, also, Melanus, Abbot in Britanny, about A. D. 617. St. Aaron, Abbot in Britanny, 6th Cent. St. Eusebius, Bp. of Samosata, A. D. 379 or 380. St. Leufredus, in French, Leufroi, Abbot, A. D. 738.

Summer Morning and Evening.

The glowing morning, crown'd with youthful roses,

Bursts on the world in virgin sweetness smiling,

And as she treads, the waking flowers expand,

Shaking their dewy tresses. Nature's choir

Of untaught minstrels blend their various powers

In one grand anthem, emulous to salute

Th' approaching king of day, and vernal Hope

Jocund trips forth to meet the healthful breeze,

To mark th' expanding bud, the kindling sky,

And join the general pćan.

While, like a matron, who has long since done

With the gay scenes of life, whose children all

Have sunk before her on the lap of earth—

Upon whose mild expressive face the sun

Has left a smile that tells of former joys—

Grey Eve glides on in pensive silence musing.

As the mind triumphs o'er the sinking frame,

So as her form decays, her starry beams

Shed brightening lustre, till on night's still bosom

Serene she sinks, and breathes her peaceful last,

While on the rising breeze sad melodies,

Sweet as the notes that soothe the dying pillow,

When angel-music calls the saint to heaven,

Come genly floating: 'tis the requiem

Chaunted by Philomel for day departed.Ado.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Viper's Buglos. Echium vulgare.

Dedicated to St. Aloysius

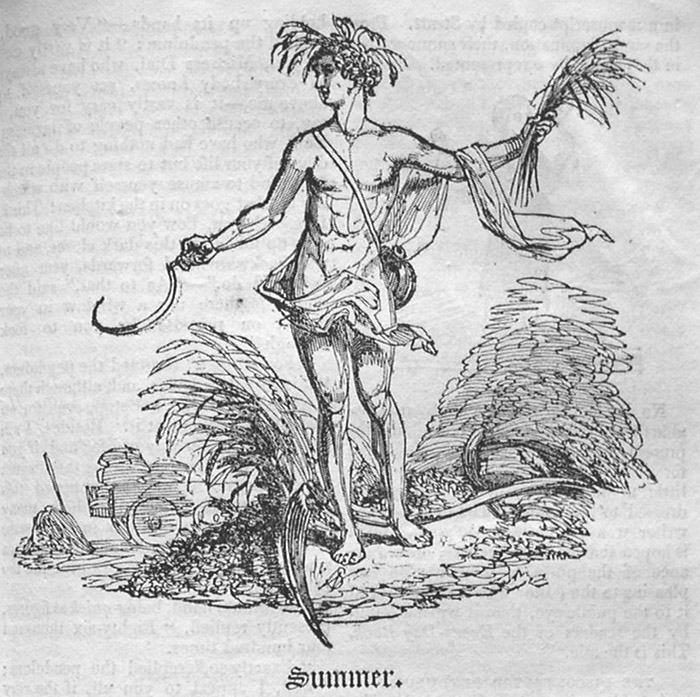

Summer.

Now cometh welcome Summer with great strength,

Joyously smiling in high lustihood,

Conferring on us days of longest length,

For rest of labour, in town, field, or wood;

Offering, to our gathering, richest stores

Of varied herbage, corn, cool fruits, and flowers,

As forth they rise from Nature's open pores,

To fill our homesteads, and to deck our bowers;

Inviting us to renovate our health

by recreation; or, by ready hand,

And calculating thought, t' improve our wealth:

And so, invigorating all the land,

And all the tenantry of earth or flood,

Cometh the plenteous Summer—full of good.*

"How beautiful is summer," says the elegant author of Sylvan Sketches, a volume that may be regarded as a sequel to the Flora Domestica, from the hand of the same lady.—"How beautiful is summer! the trees are heavy with fruit and foliage; the sun is bright and cheering in the morning; the shade of broad and leafy boughs is refreshing at noon; and the calm breezes of the evening whisper gently through the leaves, which reflect the liquid light of the moon when she is seen—

———"lifting her silver rim

Above a cloud, and with a gradual swim

Coming into the blue with all her light."

On page 337 of the present work, there is the spring dress of our ancestors in the fourteenth century, from an illumination in a manuscript copied by Strutt. From the same illustration, their summer dress in that age is here represented.

LONGEST DAY.

No day is disadvantageous to an agreeable thought or two upon "Time;" and the present, being the longest day, is selected for submitting to perusal a very pleasant little apologue from a miscellany addressed to the young. The object of the writer was evidently to do good, and it is hoped that its insertion here, in furtherance of the purpose, may not be less pleasing to the editor who first introduced it to the public eye, than it will be found by the readers of the Every-Day Book. This is the tale.

THE DISCONTENTED PENDULUM.

An old clock, that had stood for fifty years in a farmer's kitchen, without giving its owner any cause of complaint, early one summer's morning, before the family was stirring, suddenly stopped.

Upon this, the dial-plate (if we may credit the fable,) changed countenance with alarm; the hands made a vain effort to continue their course; the wheels remained motionless with surprise; the weights hung speechless; each member felt disposed to lay the blame on the others. At length the dial instituted a formal inquiry as the cause of the stagnation, when hands, wheels, weights, with one voice protested their innocence. But now a faint tick was heard below from the pendulum, who thus spoke:—

"I confess myself to be the sole cause of the present stoppage; and I am willing, for the general satisfaction, to assign my reasons. The truth is, that I am tired of ticking." Upon hearing this, the old clock became so enraged, that it was on the very point of striking.

"Lazy wire!" exclaimed the dial-plate, holding up its hands.—"Very good," replied the pendulum: "it is vastly easy for you, Mistress Dial, who have always, as every body knows, set yourself up above me,—it is vastly easy for you, I say, to accuse other people of laziness! You, who have had nothing to do all the days of your life but to stare people in the face, and to amuse yourself with watching all that goes on in the kitchen! Think, I beseech you, how you would like to be shut up for life in this dark closet, and to wag backwards and forwards, year after year, and do."—"As to that," said the dial, "Is there not a window in your house, on purpose for you to look through?"

"For all that," resumed the pendulum, "it is very dark here: and, although there is a window, I dare not stop, even for an instant, to look out at it. Besides, I am really tired of my way of life; and, if you wish, I'll tell you how I took this disgust at my employment. I happened this morning to be calculating how many times I should have to tick in the course only of the next twenty-four hours: perhaps some of you above there can give me the exact sum."

The minute hand, being quick at figures, presently replied, "Eighty-six thousand four hundred times.["]

"Exactly so," replied the pendulum; "well, I appeal to you all, if the very thought of this was not enough to fatigue one; and when I began to multiply the strokes of one day by those of months and years, really it is no wonder if I felt discouraged at the prospect; so, after a great deal of reasoning and hesitation, thinks I to myself, I'll stop."

The dial could screcely keep its countenance during this harangue; but, resuming its gravity, thus replied:—

"Dear Mr. Pendulum, I am really astonished that such a useful, industrious person as yourself should have been overcome by this sudden notion. It is true you have done a great deal of work in your time; so have we all, and are likely to do; which, although it may fatigue us to think of, the question is, whether it will fatigue us to do. Would you now do me the favour to give about half a dozen strokes, to illustrate my argument?"

The pendulum complied, and ticked six times at its usual pace.—"Now," resumed the dial, "may I be allowed to inquire, if that exertion was at all fatiguing or disagreeable to you?"

"Not in the least," replied the pendulum; "it is not of six strokes that I complain, nor of sixty, but of millions."

"Very good," replied the dial; "but recollect, that though you may think of a million strokes in an instant, you are required to execute but one; and that, however often you may hereafter have to swing, a moment will always be given you to swing in."

"That consideration staggers me, I confess," said the pendulum. "Then I hope," resumed the dial-plate, "we shall all immediately return to our duty; for the maids will lie in bed till noon, if we stand idling thus."

Upon this the weights, who had never been accused of light conduct, used all their influence in urging him to proceed; when, as with one consent, the wheels began to turn, the hand began to move, the pendulum began to swing, and, to its credit, ticked as loud as ever; while a red beam of the rising sun, that streamed through a hole in the kitchen shutter, shining full upon the dial-plate, it brightened up as if nothing had been the matter.

When the farmer came down to breakfast that morning, upon looking at the clock, he declared that his watch had gained half-an-hour in the night.

A celebrated modern writer says, "take care of the minutes, and the hours will take care of themselves." This is an admirable remark, and might be very seasonably recollected when we begin to be "weary in well-doing," from the thought of having much to do. The present moment is all we have to do with in any sense; the past is irrevocable; the future is uncertain; nor is it fair to burthen one moment with the weight of the next. Sufficient unto the moment is the trouble thereof. If we had to walk a hundred miles, we should still have to set but one step at a time, and this process continued would infallibly bring us to our journey's end. Fatigue generally begins, and is always increased, by calculating in a minute the exertion of hours.

Thus, in looking forward to future life, let us recollect that we have not to sustain all its toil, to endure all its sufferings, or encounter all its crosses at once. One moment comes laden with its own little burthens, then flies, and is succeeded by another no heavier than the last; if one could be borne, so can another, and another.

Even in looking forward to a single day, the spirit may sometimes faint from an anticipation of the duties, the labours, the trials to temper and patience that may be expected. Now, this is unjustly laying the burthen of many thousand moments upon one. Let any one resolve always to do right now, leaving then to do as it can; and if he were to live to the age of Methusalem, he would never do wrong. But the common error is to resolve to act right after breakfast, or after dinner, or to-morrow morning, or next time; but now, just now, this once, we must go on the same as ever.

It is easy, for instance, for the most ill-tempered person to resolve, that the next time he is provoked he will not let his temper overcome him; but the victory would be to subdue temper on the present provocation. If, without taking up the burthen of the future, we would always make the single effort at the present moment, while there would, at any time, be very little to do, yet, by this simple process continued, every thing would at last be done.

It seems easier to do right to-morrow than to-day, merely because we forget, that when to-morrow comes, then will be now. Thus life passes with many, in resolutions for the future, which the present never fulfils.

It is not thus with those, who, "by patient continuance in well-doing, seek for glory, honour, and immortality:" day by day, minute by minute, they execute the appointed task to which the requisite measure of time and strength is proportioned: and thus, having worked while it was called day, they at length rest from their labours, and their "works follow them."

Let us then, "whatever our hands find to do, do it with all our might, recollecting that now is the proper and accepted time."* [1]