June 15.

Sts. Vitus, or Guy, Crescentia, and Modestus, 4th Cent. St. Landelin, Abbot, A.D. 686. B. Bernard, of Menthon, A.D. 1008. St. Vauge, Hermit, A.D. 585. B. Gregory Lewis Barbadigo, Cardinal Bp. A.D. 1697.

St. Vitus.

This saint was a Sicilian martyr, under Dioclesian. Why the disease called St. Vitus's dance was so denominated, is not known. Dr. Forster describes it as an affection of the limbs, resulting from nervous irritation, closely connected with a disordered state of the stomach and bowels, and other organs of the abdomen. In papal times, fowls were offered on the festival of this saint, to avert the disease. It is a vulgar belief, that rain on St. Vitus's day, as on St. Swithin's day, indicates rain for a certain number of days following.

It is related, that after St. Vitus and his companions were martyred, their heads were enclosed in a church wall, and forgotten, so that no one knew where they were, until the church was repaired, when the heads were found, and the church bells began to sound of themselves, which causing inquiry, a writing was found, authenticating the heads; they consequently received due honour, and worked miracles in due form.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Sensitive Plant. Mimosa sinsit.

Dedicated to St. Vitus.

CEREMONY OF LAYING

THE

First Stone of the New London-bridge,

ON WEDNESDAY, THE 15TH OF JUNE, 1825.

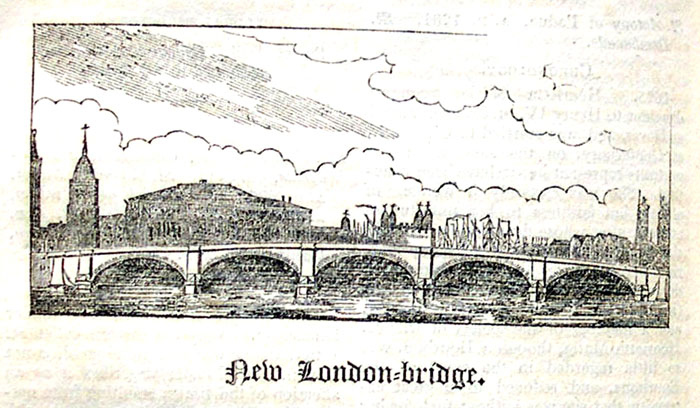

New London-bridge.

London, like famous old Briareus,

With fifty heads and twice told fifty arms,

Laid one strong arm across yon noble flood,

For free communication with each shore;

Hence, though the thews and sinews sink and shrink,

And we so manifold and strong have grown,

That a renewal of the limb for purposes

Of national and private weal be requisite,

It is to be regarded as a friend

That oft hath served us in our utmost need,

With all its strength. Be ye then merciful,

Good citizens, to this our ancient "sib,"

Operate on it tenderly, and keep

Some fragments of it, as memorials

Of its former worth: for our posterity

Will to their ancestors do reverence,

As we, ourselves, do reverence to ours.—*

The present engraving is from the design at the head of the admission tickets, and is exactly of the same form and dimensions; the tickets themselves were large cards of about the size that the present leaf will present when bound in the volume, and cut round the edges.

COPY OF THE TICKET.

Admit the Bearer

to witness THE CEREMONY of laying

THE FIRST STONE

of the

New London-bridge,

on Wednesday, the 15th day of June, 1825.

(Signed) HENy WOODTHORPE, Jun.

Clerk of the Committee.Seal

of the

City Arms.N. B. The access is from the present bridge, and the time of admission will be between the hours of twelve and two.

N° 281.

It has been truly observed of the design for the new bridge, that it is striking for its contrast with the present gothic edifice, whose place it is so soon to supply. It consists but of five elliptical arches, which embrace the whole span of the river, with the exception of a doublt pier on either side, and between each arch a single pier of corresponding design: the whole is more remarkable for its simplicity than its magnificence; so much, indeed, does the former quality appear to have been consulted, that it has not a single balustrade from beginning to end.

New London-bridge is the symbol of an honourable British merchant: it unites plainness with strength and capacity, and will be found to be more expansive and ornamental, the more its uses and purposes are considered.

The following are to be the dimensions of the new bridge:—

Centre arch—span, 150 feet; rise, 32 feet; piers, 24 feet.

Arches next the centre arch—span, 140 feet; rise, 30 feet; piers 22 feet.

Abutment arches—span, 130 feet; rise, 25 feet; abutment, 74 feet.

Total width, from water-side to water-side, 690 feet.

Length of the bridge, including the abutments, 950 feet; without the abutments, 782 feet.

Width of the bridge, from outside to outside of the parapets, 55 feet; carriage-way, 33 feet 4 inches.

"Go and set London-bridge on fire," said Jack Cade, at least so Shakspeare makes him say, to "the rest" of the insurgents, who, in the reign of Henry VI., came out of Kent, took the city itself, and there raised a standard of revolt against the royal authority. "Sooner said than done, master Cade," may have been the answer; and now, when we are about to erect a new one, let us "remember the bridge that has carried safe over." Though its feet were manifold as a centipede's, and though, in gliding between its legs, as it

"doth bestride the Thames,"

some have, ever and anon, passed to the bottom, and craft of men, and craft with goods, so perished, yet the health and wealth of ourselves, and those from whom we sprung, have been increased by safe and uninterrupted intercourse above.

By admission to the entire ceremony of laying the first stone of the new London-bridge, the editor of the Every-Day Book is enabled to give an authentic account of the proceedings from his own close observation; and therefore, collating the narratives in every public journal of the following day, by his own notes, he relates the ceremonial he witnessed, from a chosen situation within the cofferdam.

At an early hour of the morning the vicinity of the new and old bridges presented an appearance of activity, bustle, and preparation; and every spot that could command even a bird's-eye view of the scene, was eagerly and early occupied by persons desirous of becoming spectators of the intended spectacle, which, it was confidently expected, would be extremely magnificent and striking; these anticipations were in no way disappointed.

So early as twelve o'clock, the avenues leading to the old bridge were filled with inidividuals, anxious to behold the approaching ceremony, and shortly afterwards the various houses, which form the streets through which the procession was to pass, had their windows graced with numerous parties of well-dressed people. St. Magnus' on the bridge, St. Saviour's church in the Borough, Fishmongers'-hall, and the different warehouses in the vicinity, had their roofs covered with spectators; platforms were erected in every nook from whence a sight could be obtained, and several individuals took their seats on the Monument, to catch a bird's-eye view of the whole proceedings. The buildings, public or private, that at all overlooked the scene, were literally roofed and walled with human figures, clinging to them in all sorts of possible and improbable attitudes. Happy were they who could purchase seats, at from half a crown to fifteen shillings each, for so the charge varied, according to the degree of the accommodation afforded. As the day advanced, the multitude increased in the street; the windows of the shops were closed, or otherwise secured, and those of the upper floors became occupied with such of the youth and beauty of the city as has not already repaired to the river: and delightfully occupied they were: and were the sun down, as it was not, it had scarcely been missed—for there—

"From every casement came the light,

Of women's eyes, so soft and bright,

Peeping between the trelliced bars,

A nearer, dearer heaven of stars!"The wharfs on the banks of the river, between London-bridge and Southwark-bridge, were occupied by an immense multitude. Southwark-bridge itself was clustered over like a bee-hive; and the river from thence to London-bridge presented the appearance of an immense dock covered with vessels of various descriptions; or, perhaps, it more closely resembled a vast country fair, so completely was the water concealed by multitudes of boats and barges, and the latter again hidden by thousands of specatators, and canvass awnings, which, with the gay holiday company within, made them not unlike booths and tents, and contributed to strengthen the fanciful similitude. The tops of the houses had many of them also their flags and awnings; and, from the appearance of them and the river, one might almost suppose the dry and level ground altogether deserted, for this aquatic fete, worthy of Venice at her best of times. All the vessels in the pool hoisted their flags top-mast-high, in honour of the occasion, and many of them sent out their boats manned, to increase the bustle and interest of the scene.

At eleven o'clock London-bridge was wholly closed, and at the same hour Southwark-bridge was thrown open, free of toll. At each end of London-bridge barriers were formed, and no persons were allowed to pass, unless provided with tickets, and these only were used for the purpose of arriving at the coffer-dam. There was a feeling of awful solemnity at the appearance of this, the greatest thoroughfare of the metropolis, now completely vacated of all its foot-passengers and noisy vehicles.

At one o'clock the lord mayor and sheriffs arrived at Guildhall, the persons engaged in the procession having met at a much earlier hour.

The lady mayoress and a select party went to the coffer-dam in the lord mayor's private state carriage, and arrived at the bridge about half-past two o'clock.

The Royal Artillery Company arrived in the court-yard of the Guildhall at two o'clock.

The carriages of the members of parliament and other gentlemen, forming part of the procession, mustered in Queen-street and the Old Jewry.

At twelve o'clock, the barrier at the foot of the bridge on the city side of the river was thrown open, and the company, who were provided with tickets for the coffer-dam, were admitted within it, and kept arriving till two o'clock in quick succession. At that time the barriers were again closed, and no person was admitted till the arrival of the chief procession. By one o'clock, however, most of the seats within the coffer-dam were occupied, with the exception of those reserved for the persons connected with the procession.

The tickets of admission issued by the committee, consisting of members of the court of common council, were in great request. By their number being judiciously limited, and by other arrangements, there was ample accommodation for all the company. At the bottom of each ticket, there was a notice to signify that the hours of admission were between twelve and two, and not a few of the fortunate holders were extremely punctual in attending at the first mentioned hour, for the purpose of securing the best places. They were admitted at either end of the bridge, and passed on till they came to an opening that had been made in the balustrade, leading to the platform that surrounded the area of the proposed ceremony. This was the coffer-dam formed in the bed of the river, for the building of the first pier, at the Southwark side. The greatest care had been taken to render the dam water-tight, and during the whole of the day, from twelve till six, it was scarcely found necessary to work the steam-engine a single stroke. On passing the aperture in the balustrade, already mentioned, the company immediately arrived on a most extensive platform, from which two staircases divided—the one for the pink tickets, which introduced the possessor to the lowest stage of the works, and the other for the white ones, of less privilege, and which were therefore more numerous. The interior of the works was highly creditable to the committee. Not only were the timbers, whether horizontal or upright, of immense thickness, but they were so securely and judiciously bolted and pinned together, that the liability of any danger or accident was entirely done away with. The very awning which covered the whole coffer-dam, to ensure protection from the sun or rain, had there been any, was raised on a little forest of scaffolding poles, which, any where but by the side of the huge blocks of timber introduced immediately beneath, would have appeared of an unusual stability. In fact, the whole was arranged as securely and as comfortably as though it had been intended to serve the time of all the lord mayors for the next century to come, while on the outside, in the river, every necessary precaution was taken to keep off boats, by stationing officers there for that purpose. With the exception of the lower floor, which, as already mentioned, was only attainable by the possession of pink tickets, and a small portion of the floor next above it, the whole was thrown open without reservation, and the visitors took possession of the unoccupied places they liked best.

The entire coffer-dam was ornamented with as much taste and beauty as the purposes for which it was intended would possibly admit. The entrance to the platform from the bridge, was fitted up with crimson drapery, tastefully festooned. The coffer-dam itself was divided into four tiers of galleries, along which several rows of benches, covered with scarlet cloth, were arranged for the benefit of the spectators. It was covered with canvass to keep out the rays of the sun, and from the transverse beams erected to support it, which were decked with rosettes of different colours, were suspended flags and ensigns of various descriptions, brought from Woolwich yard; which by the constant motion in which they were kept, created a current of air, which was very refreshing. The floor of the dam, which is 45 feet below the high water mark, was covered, like the galleries, with scarlet cloth, except in that part of it where the first stone was to be laid. The floor is 95 feet in length, and 36 in breadth; is formed of beech planks, four inches in thickness, and rests upon a mass of piles, which are shod at the top with iron, and are crossed by immense beams of solid timber. By two o'clock all the galleries were completely filled with well-dressed company, and an eager imaptience for the arrival of the procession was visible in every countenance. The bands of the Horse Guards, red and blue, and also that of the Artillery Company, played different tunes, to render the interval of expectation as little tedious as possible; but, in spite of all their endeavours, a feeling of listlessness appeared to pervade the spectators.—In the mean time the arrangements at Guildhall being completed, the procession moved from the court-yard, in the following order:—

A body of the Artillery Company.

Band of Music.

Marshalmen.

Mr. Cope, the City Marshal, mounted, and in th[e] full uniform of his Office.

The private carriage of —Saunders, Esq., the Water Bailiff, containing the Water-Bailiff, and Nelson, his Assistant.

Carriage containing the Barge-masters.

City Watermen bearing Colours.

A party of City Watermen without Colours.

Carriage containing Messrs. Lewis and Gillman, the Bridge-master, and the Clerk of the Bridge-house Estate.

Another party of the City Watermen.

Carriage containing Messrs. Jolliffe and Sir E. Banks, the Contractors for the Building of the New Bridge.

Model of the New Bridge.

Carriages containing Members of the Royal Society.

Carriage containing John Holmes, Esq., the Bailiff of Southwark.

Carriage containing the Under-Sherrifs.

Carriages containing Thomas Shelton, Esq., Clerk of the Peace for the City of London; W. L. Newman, Esq., the City Solicitor; Timothy Tyrrell, Esq., the Remembrancer; Samuel Collingridge, Esq., and P. W. Crowther, Esq., the Secondaries; J. Boudon, Esq., Clerk of the Chamber; W. Bolland, Esq., and George Bernard, Esq., the Common Pleaders; Henry Woodthorpe, Esq., the Town Clerk; Thomas Denman, Esq., the Common Sergeant; R. Clarke, Esq., the Chamberlain.

These Carriages were followed by those of several Members of Parliament.

Carriages of Members of the Privy Council.

Band of Music and Colours, supported by City Watermen

Members of the Goldsmiths' (the Lord Mayor's) Company.

Marshalmen.

Lord Mayor's Servants in their State Liveries.

Mr. Brown, the City Marshal, mounted on horseback, and in the full uniform of his Office.

The Lord Mayor's State Carriage, drawn by six bay horses, beautifully caparisoned, in which were his Lordship and the Duke of York.

The Sheriffs, in their State Carriages.

Carriages of several Aldermen who have passed the Chair.

Another body of the Royal Artillery Company.The procession moved up Cornhill and down Gracechurch-street, to London-bridge. While awaiting the arrival of the procession, wishes were wafted from many a fair lip, that the lord of the day, as well as of the city, would make his appearance. Small-talk had been exhausted, and the merits of each particular timber canvassed for the hundredth time, when, at about a quarter to three, the lady mayoress made her appearance, and renovated the hopes of the company. They argued that his lordship as a family man, would not be long absent from his lady. The clock tolled three, and no lord mayor had made his appearance. At this critical juncture a small gun made its report; but, except the noise and smoke, it produced nothing. More than an hour elapsed before the eventful moment arrived; a flourish of trumpets in the distance gave hope to many hearts, and finally two six-pounders of the Artillery Company, discharged from the wharf at Old Swan Stairs, at about a quarter-past four o'clock, announced the arrival of the cavalcade. Every one stood up, and in a very few minutes the city watermen, bearing their colours flying, made their appearance at the head of the coffer-dam, and would, if they could, have done the same thing at the bottom of it; but owing to the unaccomodating narrowness of the staircase, they found it inconvenient to convey their flags by the same route that they intended to convey themselves. Necessity, however, has long been celebrated as the mother of invention, and a plan was hit upon to wind the flags over this timber and under that, till after a very serpentine proceeding, they arrived in safety at the bottom. After this had been accomplished, there was a sort of pause, and every body seemed to be thinking of what would come next, when some one in authority hinted, that as the descent of the flags had been performed so dextrously, or for some other reason that did not express itself, they might as easily be conveyed back, so that the company, whose patience, by the bye, was exemplary, were gratified by the ceremony of those poles returning, till the arrival of the expected personages, satisfied every desire. A sweeping train of aldermen were seen winding in the scarlet robes through the mazes of the pink-ticketed staircase, and in a very few minutes a great portion of these dignified elders of the city made their appearance on the floor below, the band above having previously struck up the "Hunter's Chorus" from Der Freischütz. Next in order entered a strong body of the common-councilmen, who had gone to meet the procession on its arrival at the barriers. Independently of those that made their appearance on the lower platform, glimpses of their purpole robes with fur-trimmings, were to be caught on every stage of the scaffolding, where many of them had been stationed throughout the day. After these entered the recorder, the common sergeant, the city solicitor, the city clerk, the city chamberlain, and a thousand other city officers, "all gracious in the city's eyes." These were followed by the duke of York and the lord mayor, advancing together, the duke being on his lordship's right hand. His royal highness was dressed in a plain blue coat with star, and wore at his knee the garter. They were received with great cheering, and proceeded immediately up the floor of the platform, till they arrived opposite the place where the first stone was suspended by a tackle, ready to be swung into the place that it is destined to occupy for centuries. Opposite the stone, an elbowed seat had been introduced into the line of bench, so as to afford a marked place for the chief magistrate, without breaking in upon the direct course of the seats. His lordship, who was in his full robes, offered the chair to his royal highness, which was positively declined on his part. The lord mayor therefore seated himself, and was supported on the right by his royal highness, and on the left by Mr. Alderman Wood. The lady mayoress, with her daughters in elegant dresses, sat near his lordship, accompanied by two fine-looking intelligent boys her sons; near them were the two lovely daughters of lord Suffolk, and many other fashionable and elegantly dressed ladies. In the train which arrived with the lord mayor and his royal highness were the earl of Darnley, lord J. Stewart, the right hon. C. W. Wynn, M. P., sir G. Warrender, M. P., sir I. Coffin, M. P., sir G. Cockburn, M. P., sir R. Wilson, M. P., Mr. T. Wilson, M. P., Mr. W. Williams, M. P., Mr. Davies Gilbert, M. P., Mr. W. Smith, M. P., Mr. Holme Sumner, M. P., with several other persons of distinction, and the common sergeant, the city pleaders, and other city officers.

The lord mayor took his station by the side of the stone, attended by four gentlemen of the committee, bearing, one, the glasscut bottle to contain the coins of the present reign, another, an English inscription incrusted in glass, another, the mallet, and another, the level.

The sub-chairman of the committee, bearing the golden trowel, took his station on the side of the stone opposite the lord mayor.

The engineer, John Rennie, esq., took his place on another side of the stone, and exhibited to the lord mayor the plans and drawings of the bridge.

The members of the committee of management, presented to the lord mayor the cut glass bottle which was intended to contain the several coins.

The ceremony commenced by the children belonging to the wards' schools, Candlewick, Bridge, and Dowgate, singing "God save the King." They were stationed in the highest eastern gallery for that purpose; the effect produced by their voices, stealing through the windings caused by the intervening timbers to the depth below, was very striking and peculiar.

The chamberlain delivered to his lordship the several pieces of coin: his lordship put them into the bottle, and deposited the bottle in the place whereon the foundation stone was to be laid.

The members of the committee, bearing the English inscription incrusted on glasses, presented it to the lord mayor. His lordship deposited it in the subjacent stone.

Mr. Jones, sub-chairman of the Bridge Committee, who attended in purple gowns and with staves, presented the lord mayor, on behalf of the committee, with an elegant silver-gilt trowel, embossed with the combined arms of the "Bridge House Estate and the City of London," and bearing on the reverse an inscription of the date, and design of its presentation to the right hon. the lord mayor, who was born in the ward, and is a member of the guild wherein the new bridge is situated. This trowel was designed by Mr. John Green, of Ludgate-hill, and excuted by Messrs. Green, Ward, and Green, in which firm he is partner. Mr. Jones, on presenting it to the lord mayor, thus addressed his lordship: "My lord, I have the honour to inform you, that the committee of management has appointed your lordship, in your character of lord mayor of London, to lay the first stone of the new London-bridge, and that they have directed me to present to your lordship this trowel as a means of assistance to your lordship in accomplishing that object."

The lord mayor having signified his consent to perform the ceremony, Henry Woodthorpe, esq., the town clerk, who has lately obtained the degree of L. L. D., held the copper plate about to be placed beneath the stone with the following inscription upon it, composed by Dr. Coplestone, master of Oriel-college, Oxford:—

Pontis Vetvati

qvvm propter crebras nimis interiectas moles

impedito cvrsv flvminis

navicvlae et rates

non levi saepe lactura et vitae pericvlo

per angvstas favces

praecipiti aqvarvm impetv ferri solerent

Civitas Londinensis

his incommodis remidium adhibere volens

et celeberrimi simvl in terris emporii

vtilitatibvs consviens

regni insvper senatva avctoritate

ac mvnificentia adivta

pontem

sitv prorsvs novo

amplioribvs spatiis constrvendvm decrev

ca scilicet forma ac magnitvdine

qvae regiae vrbis maiestari

tandem responderet. Neqve alia magis tempore

tantum opvs inchoandvm dvxit

qvam cvm pacato ferme toto terrarvm orbe

Imperivm Britannicvm

fama opibus mvltitvdine civivm et concordia pollens

principe

item gavderet

artivm favtore ac patrono

cvivs svb avspicils

novvs indies aedificiorvm splendor vrbi accederct.

Primum operis lapidem

posvit

Ioannes Garratt armiger

praetor

xv. die Ivnii

anno regis Georgii Quarti sexto

a. s. m.d.ccc.xxv.

Ioanne Rennie S. R. S. architecto.

Translation.

The free course of the river

being obstructed by the numerous piers

of the ancient bridge,

and the passage of boats and vessels

through its narrow channels

being often attended with danger and loss of life

by reason of the force and rapidity of the current,

the City of London,

desirous of providing a remedy for this evil,

and at the same time consulting

the convenience of commerce

in this vast emporium of all nations,

under the sanction and with the liberal aid of

parliament,

resolved to erect a bridge

upon a foundation altogether new,

with arches of wider span,

and of a character corresponding

to the dignity and importance

of this royal city:

nor does any other time seem to be more suitable

for such an undertaking

than when in a period of universal peace

the British empire,

flourishing in glory, wealth, population, and

domestic union,

is governed by a prince,

the patron and encourager of the arts,

under whose auspices

the metropolis has been daily advancing in

elegance and splendour.

The first stone of this work

was laid

by John Garratt, esquire,

lord mayor,

on the 15th day of June,

in the sixth year of king George the Fourth,

and in the year of our Lord

m.d.ccc.xxv.

John Rennie, F. R. S. architect.

Dr. Woodthorpe read the Latin inscription aloud, and the lord mayor, turning to the duke of York, addressed his royal highness and the rest of the company.

Lord Mayor's Speech.

"It is unnecessary for me to say much upon the purpose for which we are assembled this day, for its importance to this great commercial city must be evident; but I cannot refrain from offering a few observations, feeling as I do more than ordinary interest in the accomplishment of the undertaking, of which this day's ceremony is the primary step. I should not consider the present a favourable moment to enter into the chronology or detailed history of the present venerable structure, which is now, from the increased commerce of the country, and the rapid strides made by the sciences in this kingdom, found inadequate to its purposes, but would rather advert to the great advantages which will necessarily result from the execution of this national work. Whether there be taken into consideration, the rapid and consequently dangerous currents arising from the obstructions occasioned by the defects of this ancient edifice, which have proved destructive to human life and to property, or its difficult and incommodious approaches and acclivity, it must be a matter of sincere congratulation that we are living in times when the resources of this highly favoured country are competent to a work of such great public utility. If ever there was a period more suitable than another for embarking in national improvements, it must be the present, governed as we are by a sovereign, patron of the arts, under whose mild and paternal sway (by the blessing divine providence) we now enjoy profound peace; living under a government by whose enlightened and liberal policy our trade and manufactures are in a flourishing state; represented by a parliament whose acts of munificence shed a lustre upon their proceedings: thus happily situated, it is impossible not to hail such advantages with other feelings than those of gratitude and delight. I cannot conclude these remaks without acknowledging how highly complimentary I feel it to the honourable office I now fill, to view such an auditory as surrounds me, among whom are his majesty's ministers, several distinguished nobles of the land, the magistrates and commonalty of this ancient and loyal city, and above all, (that which must ever enlighten and give splendour to any scene,) a brilliant assembly of the other sex, all of whom, I feel assured, will concur with me in expressing an earnest wish that the new London-bridge, when completed, may reflect credit upon the architects, prove an ornament to the metropolis, and redound to the honour of its corporation. I offer up a sincere and fervent prayer, that in executing this great work, there may occur no calamity; that in performing that which is most particularly intended as a prevention of future danger, no mischief may occur with the general admiration of the undertaking."

The lord mayor's address was received with cheers. His lordship then spread the mortar, and the stone was gradually lowered by two men at a windlass. When finally adjusted, the lord mayor struck it on the surface several times with a long-handled mallet, and proceeded to ascertain the accuracy of its position, by placing a level on the top of the east end, and then to the north, west, and south; his lordship passing to each side of the stone for that purpose, and in that order. The city sword and mace were then placed on it crossways; the foundation of the new London-bridge was declared to be laid; the music struck up "God save the King;" and three times three excessive cheers, broke forth from the company; the guns of the honourable Artillery Company, on the Old Swan Wharf, fired a slaute by signal, and every face wore smiles of gratulation. Three cheers were afterwards given for the duke of York; three for Old England; and three for the architect, Mr. Rennie.

It was observed in the coffer-dam, as a remarkable circumstance, that as the day advanced, a splendid sunbeam, which had penetrated through an accidental space in the awning above, gradually approached towards the stone as the hour for laying it advance, and during the ceremony, shone upon it with dazzling lustre.

At the conclusion of the proceedings, the lord mayor, with the duke of York, and the other visitors admitted to the floor of the coffer-dam, retired; after which, many of the company in the galleries came down to view the stone, and several of the younger ones were allowed to ascend and walk over it. Some ladies were handed up, and all who were so indulged, departed with the satisfaction of being enabled to relate an achievement honourable to their feelings.

Among the candidates for a place upon the stone, was a gentleman who had witnessed the scene with great interest, and seemed to wait with considerable anxiety for an opportunity of joining in the pleasure of its transient occupants. This gentleman was P. T. W., by which initials he is known to the readers of the Morning Herald, and other journals. The lightness and agility of his person, favoured the enthusiasm of his purpose; he leapt on the stone, and there

——toeing it and heeling it,

With ball-room grace, and merry face,

Kept livelily quadrilling it,till three cheers from the spectators announced their participation in his merriment; he then tripped off with a graceful bow, amidst the clapping of hands and other testimonials of satisfaction at a performance wholly singular, because unprecedented, unimitated, and inimitable.

The lord mayor gave a grand dinner in the Egyptian-hall, at the Mansion-hoouse, to 376 guests; the duke of York, being engaged to dine with the king, could not attend. The present lord mayor has won his way to the hearts of good livers, by his entertainments, and the court of common council commenced its proceedings on the following day by honourable mention of him for this entertainment especially, and complacently received a notice to do him further honour for the general festivity of his mayoralty.

His lordship's name is Garratt; he is a tea-dealer. Stow mentions that one of similar name, and a grocer, was commemorated by an epitaph in our lady's chapel, in the church of St. Saviour's, Southwark; which church the first pier of the proposed bridge adjoins. He says,

Upon a faire stone under the Grocers' arms, is this inscription:—

Garret some cal'd him,

but that was too hye,

His name is Garrard,

who now here doth lye;

Weepe not for him

since he is gone before

To heaven, where Grocers

there are many more.* [1]

It is supposed that the first bridge of London was built between the years 993 and 1016; it was of wood. There is a vulgar tradition, that the foundation of the old stone bridge was laid upon wool-packs; this report is imagined to have arisen from a tax laid upon wool towards its construction. The first stone-bridge began in 1176, and finished in 1209, was much injured by a fire in the Borough, in 1212, and three thousand people perished. On St. George's day, 1395, there was a great justing upon it, between David, earl of Crawford, of Scotland, and lord Wells of England. It had a drawbridge for the passage of ships with provisions to Queenhithe, with houses upon it, mostly tenanted by pin and needle-makers; there was a chapel on the bridge, and a tower, whereon the heads of unfortunate partisans were placed: an old map of the city, in 1597, represents a terrible cluster; in 1598, Hentzner the German traveller, counted above thirty poles with heads. Upon this bridge was placed the head of the great chancellor, sir Thomas More, which was blown off the pole into the Thames and found by a waterman, who gave it to his daughter; she kept it during life as a relic, and directed at her death it should be placed in her arms and buried with her.

Howel, the author of "Londinopolis," in a paraphrase of some lines by Sannazarius, has this—

Encomium on London-bridge.

When Neptune from his billows London spy'd,

Brought proudly thither by a high spring-tide,

As thro' a floating wood he steer'd along,

And dancing castles cluster'd in a throng;

When he beheld a mighty bridge give law

Unto his surges, and their fury awe;

When such a shelf of cataracts did roar,

As if the Thames with Nile had chang'd her shore;

When he such massy walls, such towers did eye,

Such posts, such irons, upon his back to lye;

When such vast arches he observ'd, that might

Nineteen Rialtos make for depth and height;

When the Cerulean god these things survey'd,

He shook his trident, and, astonish'd, said,

"Let the whole earth now all the wonders count,

This bridge of wonders is the paramount."

Thus has commenced, under the most favourable auspices, a structure which is calculated to secure from danger the domestic commerce of the port of London. That such a work has not long since been executed, is attributable more to the financial difficulties under which the corporation of London has been labouring for the last quarter of a century, than to any doubts of its being either expedient or necessary. A similar design to that which is now in course of execution, was in contemplation more than thirty years ago; and we believe that many of the first architects of the day sent in plans for the removal of the old bridge, and the construction of a new bridge in its place. A want of funds to complete such an undertaking compelled the projectors of it, to abandon it for a time; but the improved condition of the finances of the corporation, the increasing commerce of the city of London with the internal parts of the country, the growing prosperity of the nation at large, and we may also add, a more general conviction derived from longer experience, that the present bridge was a nuisance which deserved to be abated, induced them to resume it, and to resume it with a zeal proportionate to the magnitude of the object which they had in view. Application was made to parliament for the grant of a sum of money to a purpose which, when considered with regard either to local or to national interests, was of great importance. That application was met with a spirit of liberality which conferred as much honour upon the party who received, as upon the party who gave, the bounty. The first results of it were beheld in the operations of to-day; the further results are in the bosom of time; but from the spirit with which the work has been commenced, we have no doubt but they will tend no less to the benefit, than the glory, of the citizens of London.* [2]

There is something peculiarly imposing and impressive in ceremonies of this description, as they are usually conducted, and we certainly do not recollect any previous spectacle of a similar nature, which can be said to have surpassed in general interest, grandeur of purpose, or spendid effect, than that just recorded.

It is at all times agreeable to a philosophical mind, and an understanding which busies itself, not only with the surface and present state of things, but also with their substance and remote tendencies, to contemplate the exercise of human power, and the triumphs of human ingenuity, whether developed in physical or mental efforts, in the pursuit of objects which comprehend a mixture of both. And perhaps, it is in a good degree attributable to this secret impulse of our nature, which operates in some degree upon all, however silent and imperceptible in its operation, that the mass of mankind are accustomed to take such an eager interest in ceremonials like the present. It is true, that show, and preparation, and bustle, and the excitement consequent upon these, are the immediate and apparent motives; but it does not therefore follow that the other reasons are inefficient, or that because they are less prominent and apparent, they are therefore inoperative. The erection of a bridge, without reference to the immediate object or the extent of its design, is pre se a triumph of art over nature—a conquering of one of these obstacles, which the latter, even in her most bountiful and propitious designs, delights to present to man, as if for the purpose of calling his powers into exercise, and affording him the quantity of excitement necessary to the happiness of a sentient being. But if we do not entertain these sentiments, and give them utterance in so many words, we nevertheless feel and act upon them. We delight to attend spectacles like the present, where the first germ of a stupendous work is to be prepared. We look round on the complicated apparatus, and the seemingly discordant and unorganized beams and blocks of wood and granite, and then we think of the simple structure, the harmonious and complete whole to which these confused elements will give birth. Such a structure is pregnant with a multitude of almost indefiniable thoughts and anticipations. We bethink ourselves of the stream of human life, which, some five years hence, will flow over the new London-bridge as thickly, and almost with as little cessation, as the waters of the Thames below: and then we reflect upon the tide of hopes and fears which that human stream will carry in its bosom! One of our first reflections will necessarily be of its adaptation to trade and commerce, of which it will then constitute a a new and immense conduit. Trade, and science, and learning, and war, (Providence long avert it!) will at various periods pass across it. Next we consider what will be the immediate and individual destiny of the structure:— is it to moulder away after the lapse of many ages, under the slow but effectual influence of time, or to suffer dilapidation suddenly from the operation of some natural convulsion? Will it fall before the wrath or wilfulness of man, or is it to be displaced by new improvements and discoveries, in like manner as its old and many-arched neighbour makes way for it—and as that once superseded its narrower and shop-covered predecessor? These are questions which the imaginative man may ask himself; but who is to answer? However, even the man of business may be well excused in indulging some speculations such as these, upon the occasion of the erection of a structure, which is to constitute a new artery to and fro in the mighty heart of London—a fresh vein through which that commerce, which is the life-blood of our national prosperity and greatness will have to flow.* [3]

This is one of those public occurrences which may be considered as an event in a man's life, and an epoch in the city's history—a sort of station in one's worldly journey, from which we measure our distances and dates. To witness the manner and the moment, in which is laid the first single resting stone of a grand national structure—the very origin of the existence of a massive and magnificent pile, which will require years to complete, and ages to destroy, has an elevating and sublime effect on on the mind.

Great public works are the truest sings of a nation's prosperity and power; originally its grandest ornaments, and ultimately the strongest proofs of its existence. Its religion, language, arts, sciences, government, and history, may be swept into nothingness; but yet its national buildings will remain entire through the lapse of successive ages—after their very founders are forgotten—after their local history has become a mere matter of conjection. The columns of Palmyra stand over the ashes of their framers, in a desert as well of history as of sand. The palaces of imperial Rome are still existing, though her religion, her very language, is dead; and the history of the man-wrought miracles of Egypt, had been looked at but as the very dreamings of philosophy long before Napoleon said to his Egyption [sic] army—"From the summits of these pyramids, forty centuries are looking down upon you."

Of all public edifices, a bridge is the most necessary, the most generally and frequently useful—open at all hours and to all persons. It was probably the very first public building. Some conjecture, that the first hint of it was taken from an uprooted tree lying across a narrow current. What a difference between that first natural bridge, and the perfection of pontifical architecture—the vast, solid, and splendid Waterloo—the monumentum si quœras of John Rennie. We feel pleasure in learning, that the new London-bridge has been designed by the same distinguished architect. It falls to the lot of the son to consummate the plans of the father—we hope with equal success, and with similar benefits, as well to the conductor as to the public.

Old London-bridge, for which the new one is intended as a more commodious substitute, was the first that connected the Surrey and Middlesex banks. It was built originally of wood, about 800 years ago, and rebuilt of stone in the reign of king John, 1209, just two years after the chief civic officer assumed the name of mayor. Until the middle of the last century, it was crowded with houses, which made it very inconvenient to the passengers. The narrowness and inequality of its arches, have caused it to be compared to "a thick wall, pierced with small uneven holes, through which the water, dammed up by this clumsy fabric, rushes, or rather leaps, with a velocity extremely dangerous to boats and barges." Of its nineteen arches, none except the centre, which was formed by throwing two into one, is more than twenty feet wide. This is but the width of each of the piers of Waterloo-bridge. It is the most crowded thoroughfare in London, and, in this point, exceeds Charing-cross, which, according to Dr. Johnson, was overflowed by the full tide of human existence. It has been calculated, that there daily pass over London-bridge 90,000 foot passengers; 800 waggons; 300 carts and drays; 1,300 coaches; 500 gigs and tax carts; and 800 saddle horses. The importance of this great point of communication, and the necessity of rendering it adequate to the purposes of its construction, are proved, by the numbers to whom it affords a daily passage at present, and, still more, by the probable increase of the numbers hereafter. The present bridge having been for some years considered destitute of the proper facilities of transition for passengers as well as for vessels, an Act of Parliament, passed in 1823, for building a new one, on a scale and plan equal to the other modern improvements of the metropolis. The first pile of the works was driven on the west side of the present bridge, in March, 1824, and the first coffer-dam having been lately finished, the ceremony of laying the first stone of the new bridge, has been happily and auspiciously completed.* [4]

MRS. BARBAULD.

The decease of this literary and excellent lady in the spring of 1825, occasioned a friend to the Every-Day Book to transmit the following fugitive poem for insertion. It is not collected in any of the works published by Mrs. Barbauld during her lifetime; this, and the rectitude of spirit in the production itself, may justify its being recorded within these pages.

To her honoured Friends

of the families of

MARTINEAU AND TAYLOR

These lines are inscribed

By their affectionate

A. L. BARBAULD

On the Death

OF

MRS. MARTINEAU.

Ye who around this venerated bier

In pious anguish pour the tender tear,

Mourn not!—'Tis Virtue's triumph, Nature's doom,

When honoured Age, slow bending to the tomb,

Earth's vain enjoyments past, her transient woes,

Tastes the long sabbath of well-earned repose.

No blossom here, in vernal beauty shed,

No lover lies, warm from the nuptial bed;

Here rests the full of days,—each task fulfilled,

Each wish accomplished, and each passion stilled.

You raised her languid head, caught her last breath,

And cheered with looks of love the couch of death.Yet mourn!—for sweet the filial sorrows flow,

When fond affection prompts the gush of woe;

No bitter drop, 'midst Nature's kind relief,

Sheds gall into the fountain of your grief;

No tears you shed for patient love abused,

And counsel scorned, and kind restraints refused.

Not yours the pang the conscious bosom wrings,

When late remorse inflicts her fruitless stings.

Living you honoured her, you mourn for, dead;

Her God you worship, and her path you tread.

Your sighs shall aid reflection's serious hour,

And cherished virtues bless the kindly shower:

On the loved theme your lips unblamed shall dwell;

Your lives, more eloquent, her worth shall tell.

—Long may that worth, fair Virtue's heritage,

From race to race descend, from age to age!

Still purer with transmitted lustre shine

The treasured birthright of the spreading line!For me, as o'er the frequent grave I bend,

And pensive down the vale of years descend;

Companions, Parents, Kindred called to mourn,

Dropt from my side, or from my bosom torn;

A boding voice, methinks, in Fancy's ear

Speaks from the tomb, and cries "Thy friends are here!"

Summer Evening's Adventure in Wales.

Mr. Proger of Werndee, riding in the evening from Monmouth, with a friend who was on a visit to him, heavy rain came on, and they turned their horses a little out of the road towards Perthyer. "My cousin Powell," said Mr. Proger, "will, I am sure, be ready to give us a night's lodging." At Perthyer all was still; the family were abed. Mr. Proger shouted aloud under his cousin Powell's chamber-window. Mr. Powell soon heard him; and putting his head out, inquired, "In the name of wonder what means all this noise? Who is there?" "It is only your cousin Proger of Werndee, who is come to your hospitable door for shelter from the inclemency of the weather; and hopes you will be so kind as to give him, and a friend of his, a night's lodging." "What is it you, cousin Proger? You, and your friend shall be instantly admitted; but upon one condition, namely, that you will admit now, and never hereafter dispute, that I am the head of your family." "What was that you said?" replied Mr. Proger. "Why, I say, that if you expect to pass the night in my house, you must admit that I am the head of your family." "No, sir, I never will admit that—were it to rain swords and daggers, I would ride through them this night to Werndee, sooner than let down the consequence of my family by submitting to such an ignominious condition. Come up, Bald! come up!" "Stop a moment, cousin Proger; have you not often admitted, that the first earl of Pembroke (of the name of Herbert) was a younger son of Perthyer; and will you set yourself up above the earls of Pembroke?" "True it is I must give place to the earl of Pembroke, because he is a peer of the realm; but still, though a peer, he is of the youngest branch of my family, being descended from the fourth son of Werndee, who was your ancestor, and settled at Perthyer, whereas I am descended from the eldest son. Indeed, my cousin Jones of Lanarth is of a branch of the family elder than you are; and yet he never disputes my being the head of the family." "Well, cousin Proger, I have nothing more to say: good night to you."—"Stop a moment, Mr. Powell," cried the stranger, "you see how it pours; do let me in at least; I will not dispute with you about our families." "Pray, sir, what your name, and where do you come from?" "My name is so and so; and I come from such a county." "A Saxon of course; it would indeed be very curious, sir, were I to dispute with a Saxon about family. No, sir, you must suffer for the obstinacy of your friend, so good night to you both."* [5]