May 8.

The Apparition of St. Michael the Archangel. St. Peter, Abp. of Tarentaise, or Monstiers, A.D. 1174. St. Victor, A.D. 303. St. Wiro, Bp. 7th Cent. St. Odrian, Bp. of Waterford. St. Gybrian, or Gobrian, 8th Cent.

ST. MICHAEL. THE ARCHANGEL.

It is not clear what particular apparition of St. Michael is celebrated in the Roman Catholic church on this day; their books mention several of his apparitions. They rank him as field-marshal and commander-in-chief of the armies of heaven, as prince of the angels opposed to Lucifer, and, especially, as principal guardian of human souls against the infernal powers.* [1] In heraldry, as head of the order of archangels, his ensign is a banner hanging on a cross, and he is armed as Victory, with a dart in one hand, and a cross on his forehead, or the top of the head; archangels are distinguished from angels by that sign. Usually, however, he is painted in coat-armour, in a glory, with a dart, throwing Lucifer headlong into a flame of fire issuing out of a base proper; this is also termed the battle between Michael and the devil, with his casting out of heaven into the lake of fire and brimstone. "There remained," says a distinguishing herald, "still in heaven, after the fall of Lucifer, the bright star, and his company, more angels than there ever was, is, and shall be men born in the earth, which God ranked into nine orders or chorus, called the nine quoires of holy angels."† [2]

St. Michael is further represented in catholic books as engaged with weighing souls in a pair of scales. A very curious spiritualizing romance, originally in French, printed in English by Caxton, in the reign of Edward V., exemplifies the office of St. Michael in this capacity; the work is entitled—"The Pilgremage of the Sowle." The author expresses himself under "the similitude of a dream," which, he says, befell him on a St. Laurence' night sleeping in his bed. He thought himself travelling towards the city of Jerusalem, when death struck his body and soul asunder; whereupon Satan in a foul and horrible form came towards the soul, which being in great terror, its warden, or guardian angel, desired Satan to flee away and not meddle with it. Satan refuses, alleging that God had permitted that no soul which had done wrong should, on its passage, escape from being "snarlyd in his trappe;" and he said, that the guardian angel well knew that he, the said guardian, could never withdraw the soul from evil, or induce it to follow his good counsel; and that even if he had, the soul would not have thanked him for it; Satan, therefore, knew not why the angel should interfere, and begged he would let him alone to do with the soul what he had a right to do, and could not be prevented from doing. The parley continued, until they agreed to carry the soul before Michael, the provost of heaven, and abide his award on Satan's claim.

The soul was then lifted between them both into the transparent air, wherein the spirits of the newly dead were passing thickly on every side, to and fro, as motes flitting in the sun-beam. They tarried not until they arrived at a marvellous place of bright fire, shining with a brilliant light, surrounded by a great multitude of souls attending there for a like purpose. The guardian angel entered, leaving Satan without, and also the soul, who could hear the voice of his warden speaking in his behalf, and acquainting Michael that he had brought from earth a pilgrim, who was without, and with him Satan his accuser, abiding judgment.

Then Satan began to cry out and said, "Of right he is mine, and that I shall prove; wherefore deliver him to me by judgment, for I abide naught else." This caused proclamation to be made by sound of trumpet in these words:—"All ye that are without, awaiting your judgment, present yourselves before the provost to receive your doom; but first ye that have longest waited, and especially those that have no great matter and are not much troubled; for the plain and light causes shall first be determined, and then other matters that need greater tarrying."

This proclamation greatly disturbed the souls without. Satan and his evil spirits were most especially angry, and holding a consultation, he spoke as follows: "It appears we are of little consequence, and hence our wicked neighbours do us injustice. These wardens hinder us from our purposes, and we are without favour. There is no caitiff pilgrim but hath had a warden assigned him from his birth, to attend him and defend him at all times from our hands, and especially from the time that he washed in the 'salt lye,' ordained by grace d Dieu, who hath ever been our enemy; and then they are taken, as soon as these wardens come, before the provost, and have audience at their own pleasure; while we are kept here without, as mere ribalds. Let us cry out a rowe [haro], and out upon them all! they have done us wrong; and we will speak so loud that in spite of them they shall hear us." Then Satan and his spirits cried out all at once, "Michael! provost, lieutenant, and commissary of the high judge! do us right, without exception or favour of any party. You know very well that in every upright court the prosecutor is admitted to make his accusation and propose his petition; but you first admit the defendant to make his excusation. This manner of judging is suspicious; for were these pilgrims innocent yet, if reason were to be heard, and right were to prevail, the accusers would have the first hearing to say what they would, and then the defendants after them, to excuse themselves if they could: we, then, being the prosecutors, hear us first, and then the defendants."

After Satan's complaint, the soul heard within the curtain, "a longe parlament;" and, at the last, there was another proclamation ordered by sound of trumpet, as follows:—All ye that are accustomed to come to our judgments, to hear and to see, as assessors, that right be performed, come forth immediately and take your seats; ye well knowing your own assigned places. Ye also that are without, waiting the sitting of the court, present yourselves forthwith to the judgment thereof, in order as ye shall be called; so that no one hinder another, or interrupt another's discourse. Ye pilgrims, approach the entrance of this curtain, awaiting without; and your wardens, because they are our equals, belonging to our company, are to appear, as of right they ought, within our presence."

After this proclamation was observed, the guardian angel said,—"Provost Michael! I here present to you this pilgrim, committed to my care in the world below: he has kept his faith to the last, and ought to be received into the heavenly Jerusalem, whereto his body hath long been travelling."—Satan answered—"Michael! attend to my word and I shall tell you another tale." The soul being befriended throughout by St. Michael, finally escapes the dreadful doom of eternal punishment.

On St. Michael's contention with the devil about the body of Moses, more may be seen in the volume on "Ancient Mysteries," from which the present notice is extracted, or in "Bishop Marsh's translation of Michaeli's Introduction to the New Testament."

The managers of an institution for the encouragement of British talent, less versed in biblical criticism than in art, lately offered a prize to the painter who should best represent this strange subject.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Lily of the Valley. Convallaria majalis

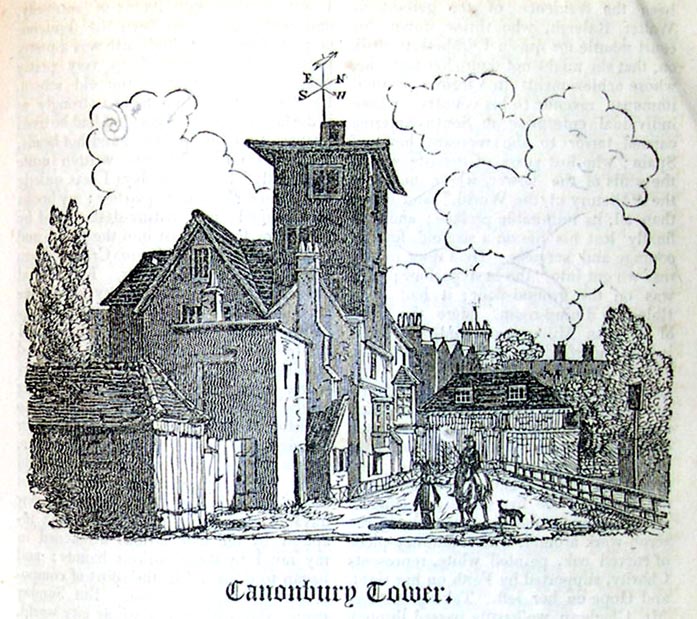

Dedicated to St. Selena.Canonbury Tower.

People methinks are better, but the scenes

Wherein my youth delighted are no more.

I wander out in search of them, and find

A sad deformity in all I see.

Strong recollections of my former pleasures,

And knowledge that they never can return,

Are causes of my sombre mindedness:

I pray you then bear with my discontent.*

A walk out of London is, to me, an event; I have an every-day desire to bring it about, but weeks elapse before the time arrives whereon I can sally forth. In my boyhood, I had only to obtain parental permission, and stroll in fields now no more,— to scenes now deformed, or that I have have been wholly robbed of, by "the spirit of improvement." Five and thirty years have altered every thing — myself with the rest. I am obliged to "ask leave to go out," of time and circumstance; or to wait till the only enemy I cannot openly face has ceased from before me—the north-east wind—or to brave that foe and get the worst of it. I did so yesterday. "This is the time," I said to an artist, "when we Londoners begin to get our walks; we will go to a place or two that I knew many years ago, and see how they look now; and first to Canonbury-house."

Having crossed the back Islington-road, we found ourselves in the rear of the Pied Bull. Ah! I know this spot well: this stagnant pool was a "famous" carp pond among boys. How dreary the place seems! the yard and pens were formerly filled with sheep and cattle for Smithfield market; graziers and drovers were busied about them; a high barred gate was constantly closed; now all is thrown open and neglected, and not a living thing to be seen. We went round to the front, the house was shut up, and nobody answered to the knocking. It had been the residence of the gallant sir Walter Raleigh, who threw down his court mantle for queen Elizabeth to walk on, that she might not damp her feet; he, whose achievements in Virginia secured immense revenue to his country; whose individual enterprise in South America carried terror to the recreant heart of Spain; who lost years of his life within the walls of the Tower, where he wrote the "History of the World," and better than all, its inimitable preface; and who finally lost his life on a scaffold for his courage and services. By a door in the rear we got into "the best parlour;" this was on the ground-floor; it had been Raleigh's dining-room. Here the arms of sir John Miller are painted on glass in the end window; and we found Mr. John Cleghorn sketching them. This gentleman, who lives in the neighbourhood, and whose talents as a draftsman and engraver are well known, was obligingly communicative; and we condoled on the decaying memorials of past greatness. On the ceiling of this room are stuccoed the five senses; Feeling in an oval centre, and the other four in the scroll-work around. The chimney-piece of carved oak, painted white, represents Charity, supported by Faith on her right, and Hope on her left. Taking leave of Mr. Cleghorn, we hastily passed through the other apartments, and gave a last farewell look at sir Walter's house; yet we bade not adieu to it till my accompanying friend expressed a wish, that as sir Walter, according to tradition, had there smoked the first pipe of tobacco drawn in Islington, so he might have been able to smoke the last whiff within the walls that would in a few weeks be levelled to the ground.

We got to Canonbury. Geoffrey Crayon's "Poor Devil Author" sojourned here:—

"Chance threw me," he says, "in the way of Canonbury Castle. It is an ancient brick tower, hard by 'merry Islington;' the remains of a hunting-seat of queen Elizabeth, where she took the pleasure of the country when the neighbourhood was all woodland. What gave it particular interest in my eyes was the circumstance that it had been the residence of a poet. It was here Goldsmith resided when he wrote his 'Deserted Village.' I was shown the very apartment. It was a relic of the original style of the castle, with pannelled wainscots and Gothic windows. I was pleased with its air of antiquity, and with its having been the residence of poor Goldy. 'Goldsmith was a pretty poet,' said I to myself, 'a very pretty poet, though rather of the old school. He did not think and feel so strongly as is the fashion now-a-days; but had he lived in these times of hot hearts and hot heads, he would no doubt have written quite differently.' In a few days I was quietly established in my new quarters; my books all arranged; my writing-desk placed by a window looking out into the fields, and I felt as snug as Robinson Crusoe, when he had finished his bower. For several days I enjoyed all the novelty of change and the charms which grace new lodgings before one has found out their defects. I rambled about the fields where I fancied Goldsmith had rambled. I explored merry Islington; ate my solitary dinner at the Black Bull, which, according to tradition, was a country seat of sir Walter Raleigh, and would sit and sip my wine, and muse on old times, in a quaint old room where many a council had been held. All this did very well for a few days; I was stimulated by novelty; inspired by the associations awakened in my mind by these curious haunts; and began to think I felt the spirit of composition stirring with me. But Sunday came, and with it the whole city world, swarming about Canonbury Castle. I could not open my window but I was stunned with shouts and noises from the cricket ground; the late quiet road beneath my window was alive with the tread of feet and clack of tongues; and, to complete my misery, I found that my quiet retreat was absolutely a 'show house,' the tower and its contents being shown to strangers at sixpence a head. There was a perpetual tramping up stairs of citizens and their families to look about the country from the top of the tower, and to take a peep at the city through the telescope, to try if they could discern their own chimneys. And then, in the midst of a vein of thought, or a moment of inspiration, I was interrupted, and all my ideas put to flight, by my intolerable landlady's tapping at the door, and asking me if I would 'just please to let a lady and gentleman come in, to take a look and R. Goldsmith's room.' If you know any thing what an author's study is, and what an author is himself, you must know that there was no standing this. I put a positive interdict on my room's being exhibited; but then it was shown when I was absent, and my papers put in confusion; and on returning home one day I absolutely found a cursed tradesman and his daughters gaping over my manuscripts, and my landlady in a panic at my appearance. I tried to make out a little longer, by taking the key in my pocket; but it would not do. I overheard mine hostess one day telling some of her customers on the stairs that the room was occupied by an author, who was always in a tantrum if interrupted; and I immediately perceived, by a slight noise at the door, that they were peeping at me through the keyhole. By the head of Apollo, but this was quite too much! With all my eagerness for fame, and my ambition of the stare of the million, I had no idea of being exhibited by retail, at sixpence a head, and that through a key-hole. So I bade adieu to Canonbury Castle, merry Islington, and the haunts of poor Goldsmith, without having advanced a single line in my labours."

Now for this and some other descriptions, I have a quarrel with the aforesaid Geoffrey Crayon, gent. What right has a transatlantic settler to feelings in England? He located in America, but it seems he did not locate his feelings there; if not, why not? What right has he of New York to sit "solitary" in Raleigh's house at Islington, and "muse" on our "old times;" himself clearly a pied animal, mistaking the pied bull for a "black" bull. There is "black" blood between us. By what authority has he a claim to a domicile at Canonbury? Under what international law laid down by Vattel or Martens, or other jurist, ancient or modern, can his pretension to feel and muse at sir Walter's or queen Elizabeth's tower, be admitted? He comes here and describes as if he were a real Englishman; and claims copyright in our courts for his feelings and descriptions, while he himself is a copyist; a downright copyist of my feelings, who am and Englishman, and a forestaller of my descriptions—bating the "black" bull. He has left me nothing to do.

My friend, the artist, obligingly passed the door of Canonbury tower to take a sketch of its north-east side; not that the tower has not been taken before, but it has not been given exactly in that position. We love every look of an old friend, and this look we get after crossing the bridge of the New River, coming from the "Thatched house" to "Canonbury tavern." A year or so ago, the short walk from the lower Islington-road to this bridge was the prettiest "bit" on the river nearest to London. Here the curve of the stream formed the "horse-shoe." In by-gone days only three or four hundred, from the back of Church-street southerly, and from the back of the upper street westerly, to Canonbury, were open green pastures with uninterrupted views easterly, bounded only by the horizon. Then the gardens to the houses in Canonbury-place, terminated by the edge of the river, were covetable retirements; and ladies, lovely as the marble bust of Mrs. Thomas Gent, by Behnes, in the Royal Academy Exhibition, walked in these gardens, "not unseen," yet not obtruded on. How, how changed!

My ringing at the tower-gate was answered by Mr. Symes, who for thirty-nine years past has been resident in the mansion, and is bailiff of the manor of Islington, under lord Northampton. Once more, to "many a time and oft" aforetime, I ranged the old rooms, and took perhaps a last look from its roof. The eye shrunk from the wide havoc below. Where new buildings had not covered the sward, it was embowelling for bricks, and kilns emitted flickering fire and sulphurous stench. Surely the dominion of the brick-and-mortar king will have no end; and cages for commercial spirits will be instead of every green herb. In this high tower some of our literary men frequently shut themselves up, "far from the busy haunts of men." Mr. Symes says that his mother-in-law, Mrs. Evans, who had lived there three and thirty years, and was wife to the former bailiff, often told him that her aunt, Mrs. Tapps, a seventy years; inhabitant of the tower, was accustomed to talk much about Goldsmith and his apartment. It was the old oak room on the first floor. Mrs. Tapps affirmed that he there wrote his "Deserted Village," and slept in a large press bedstead, placed in the eastern corner. From this room two small ones for sleeping in have since been separated, by the removal of the pannelled oak wainscotting from the north-east wall, and the cutting of two doors through it, with a partition between them; and since Goldsmith was here, the window on the south side has been broken through. Hither have I come almost every year, and frequently in many years, and seen the changing occupancy of these apartments. Goldsmith's room I almost suspect to have been tenanted by Geoffrey Crayon; about seven years ago I saw books on one of the tables, with writing materials, and denotements of more than a "Poor Devil Author." This apartment, and other apartments in the tower, are often to be let comfortably furnished, "with other conveniences." It is worth while to take a room or two, were it only to hear Mr. Symes's pleasant conversation about residences and residentiaries, manorial rights and boundaries, and "things as they used to be" in his father's time, who was bailiff before him, and "in Mrs. Evans's time," or "Mrs. Tapps's time." The grand tenantry of the tower has been in and through him and them during a hundred and forty-two years.

Canonbury tower is sixty feet high, and seventy feet square. It is part of an old mansion which appears to have been erected, or, if erected before, much altered about the reign of Elizabeth. The more ancient edifice was erected by the priors of the canons of St. Bartholomew, Smithfield, and hence was called Canonbury, to whom it appertained until it was surrendered with the priory to Henry VIII.; and when the religious houses were dissolved, Henry gave the manor to Thomas lord Cromwell; it afterwards passed through other hands till it was possessed by sir John Spencer, an alderman and lord mayor of London, known by the name of "rich Spencer." While he resided at Canonbury, a Dunkirk pirate came over in a shallop to Barking creek, and hid himself with some armed men in Islington fields, near to the path sir John usually took from his house in Crosby-place to this mansion, with the hope of making him prisoner; but as he remained in town that night, they were glad to make off, for fear of detection, and returned to France disappointed of their prey, and of the large ransom they calculated on for the release of his person. His sole daughter and heiress, Elizabeth, was carried off in a baker's basket from Canonbury-house by William, the second lord Compton, lord president of Wales. He inherited Canonbury, with the rest of sir John Spencer's wealth at his death, and was afterwards created earl of Northampton; in this family the manor still remains. The present earl's rent-roll will be enormously increased, by the extinction of comfort to the inhabitants of Islington and its vicinity, through the covering up of the open fields and verdant spots on his estates.

As a custom it is noticeable, that many metropolitans visit this antique edifice in summer, for the sake of the panoramic view from the roof. To those who inquire concerning the origin or peculiarities of its erection or history, Mr. Symes obligingly tenders the loan of "Nelson's History of Islington," wherein is ample information on these points. In my visit, yesterday, I gathered one or two particulars from this gentleman not befitting me to conceal, inasmuch as I hold and maintain that the world would not be the worse for being acquainted with what every one knows; and that it is every one's duty to contribute as much as he can to the amusement and instruction of others. Be it known then, that Mr. Symes says he possesses the ancient key of the gate belonging to the prior's park. "It formerly hung there," said he, pointing with his finger as we stood in the kitchen, "withinside that clock-case, but by some accident it has fallen to the bottom, and I cannot get at it." The clock-case is let into the solid wall flush with the surface, and the door to the weights opening only a small way down from the dial plate, they descend full two-thirds the length of their lines within a "fixed abode." Adown this space Mr. Symes has looked, and let down inches of candle without being able to see, and raked with long stick without being able to feel, the key; and yet he thinks it there, in spite of the negative proof, and of a suggestion I uncharitably urged, that some antiquary, with confused notions as to the "rights of things," might have removed the key from the nail in the twinkling of Mr. Symes's eye, and finally deposited it among his own "collections." A very large old arm chair, with handsome carved claws, and modern verdant baize on the seat and back, which also stands in the kitchen, attracted my attention. "It was here," said Mr. Symes, "before Mrs. Tapps's time; the old tapestry bottom was quite worn out, and the tapestry back so ragged, that I cut them away, and had them replaced as you see; but I have kept the back, because it represents Queen Elizabeth hunting in the woods that were hereabout in her time—I'll fetch it." On my hanging this tapestry against the clock-case, it was easy to make out a lady gallantly seated on horseback, with a sort of turbaned headdress, and about to throw a spear from her right hand; a huntsman on foot, with a pole in one hand, and leading a brace of dogs with the other, runs at the side of the horse's head; and another man on foot, with a gun on his shoulder, follows the horse; the costume, however, is not so early as the time of Elizabeth; certainly not before the reign of Charles I.

This edifice is well worth seeing, and Mr. Symes's plain civility is good entertainment. Readers have only to ring at the bell above the brass plate with the word "Tower" on it, and ask, "Is Mr. Tower at home?" as I do, and they will be immediately introduced; at the conclusion of the visit the tender of sixpence each, by way of "quit-rent," will be accepted. Those who have been before and not lately, will view "improvement" rapidly devastating the forms of nature around this once delightful spot; others who have not visited it at all may be amazed at the extensive prospects; and none who see the "goings on" and "ponder well," will be able to foretell whether Mr. Symes or the tower will enjoy benefit of survivorship.

To Canonbury Tower.

As some old, stout, and lonely holyhock,

Within a desolate neglected garden,

Doth long survive beneath the gradual choke

Of weeds, that come and work the general spoil;

So, Canonbury, thou dost stand awhile:

Yet fall at last thou must; for thy rich warden

Is fast "improving;" all thy pleasant fields

Have fled, and brick-kilns, bricks, and houses rise

At his command; the air no longer yields

A fragrance—scarcely health; the very skies

Grow dim and townlike; a cold, creeping gloom

Steals into thee, and saddens every room:

And so realities come unto me,

Clouding the chambers of my mind, and making me—like thee.*

Rogation Sunday.

This is the fifth sunday after Easter. "Rogation" is supplication, from the Latin rogare, to beseech.

Rogation Sunday obtained its name from the succeeding Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, which are called Rogation-days, and were ordained by Mammertus, archbishop of Vienne, in Dauphiné; about the year 469 he caused the litanies, or supplications, to be said upon them, for deliverance from earthquakes, fires, wild beasts, and other public calamities, which are alleged to have happened in his city; hence the whole week is called Rogation-week, to denote the continual praying.* [3]

Shepherd, in his "Elucidation of the Book of Common Prayer," mistaking Vienne for Vienna the capital of Germany, says: "The example of Mammertus was followed by many churches in the West, and the institution of the Rogation-days, soon passed from the diocese of Vienna into France, and from France into England."

Rogation-week is also called grass-week, from the appetite being restricted to salads and greens; cross-week, from the cross being more than ordinarily used; procession-week, from the public processions during the period; and gant-week, from the ganging, or going about in these processions.* [4]

The rogations and processions, or singing of litanies along the streets during this week, were practised in England till the Reformation. In 1554, the priests of queen Mary's chapel made public processions. "All the three days there went her chapel about the fields: the first day to St. Giles's, and there sung mass: the next day, being Tuesday, to St. Martin's in the Fields; and there a sermon was preached, and mass sung; and the company drank there: the third day to Westminster; where a sermon was made, and then mass and good cheer made; and after, about the park, and so to St. James's court. The same Rogation-week went out of the Tower, on procession, priests and clerks, and the lieutenant with all his waiters; and the axe of the Tower borne in procession: the waits attended. There joined in this procession the inhabitants of St. Katharine's, Radcliff, Lime-house, Poplar, Stratford, Bow, Shoreditch, and all those that belonged to the Tower, with their halberts. They went about the fields of St. Katharine's, and the liberties."* [5] On the following Thursday, "Being Holy Thursday, at the court of St. James's, the queen went in procession within St. James's, with heralds and serjeants of arms, and four bishops mitred; and bishop Bonner, beside his mitre, wore a pair of slippers of silver and gilt, and a pair of rich gloves with ouches of silver upon them, very rich."† [6]

The effect of processions in the churches, must have been very striking. A person sometimes inquires the use of a large portion of unappropriated room in some of our old ecclesiastical edifices; he is especially astonished at the enormous unoccupied space in a cathedral, and asks, "what is it for?"—the answer is, at this time, nothing. But if the Stuarts had succeeded in reestablishing the catholic religion, then this large and now wholly useless portion of the structure, would have been devoted to the old practices. In that event, we should have had cross-carrying, canopy-carrying, censing, chanting, flower-strewing, and all the other accessories and essentials of the grand pageantry, which distinguishes catholic from protestant worship. The utmost stretch of episcopal ceremonial in England, can scarcely extend to the use of an eighth part of any of our old cathedrals, each of which, in every essential particular as a building, is papal.