January 22.

St. Vincent.In the church of England calendar.† [1]

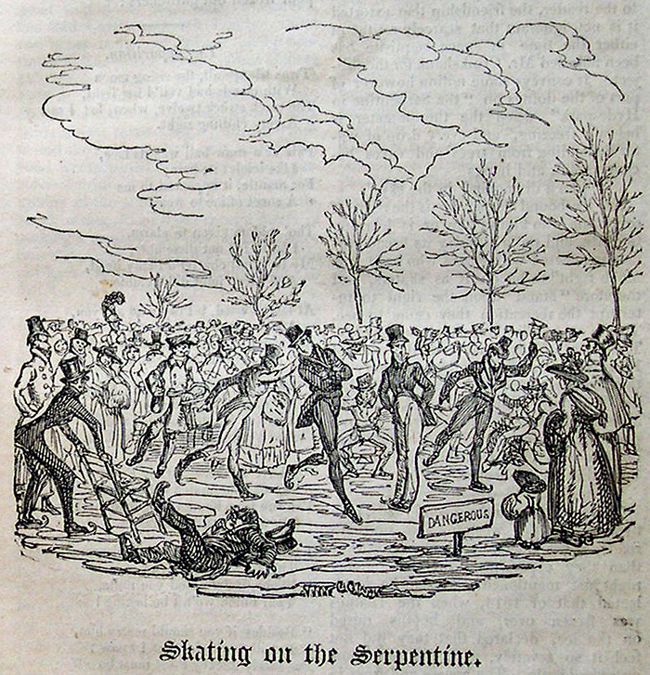

Skating on the Serpentine.The Hyde-park river—which no river is,

The Serpentine—which is not serpentine,

When frozen, every skater claims as his,

In right of common, there to intertwine

With countless crowds, and glide upon the ice.

Lining the banks, the timid and unwilling

Stand and look on, while some the fair entice

By telling, "yonder skaters are quadrilling"—

And here the skateless hire the "best skates" for a shilling.*

A hard frost is a season of holidays in London. The scenes exhibited are too agreeable and ludicrous for the pen to describe. They are for the pencil; and Mr. Cruikshank's is the only one equal to the series. In a work like this there is no room for their display, yet he has hastily essayed the preceding sketch in a short hour. It is proper to say, that however gratifying the representation may be to the reader, the friendship that extorted it is not ignorant that scarcely a tithe of either the time or space requisite has been afforded Mr. Cruikshank for the subject. It conveys some notion however of part of the doings on "the Serpentine in Hyde-park" when the thermometer is below "freezing," and every drop of water depending from trees and eaves becomes solid, and hangs

"like a diamond in the sky."

The ice-bound Serpentine is the resort of every one who knows how or is learning to skate, and on a Sunday its broad surface is covered with gazers who have "as much right" to be on it as skaters, and therefore "stand" upon the right to interrupt the recreation they came to see. This is especially the case on a Sunday. The entire of this canal from the wall of Kensington-gardens to the extremity at the Knightsbridge end was, on Sunday the 15th of January, 1826, literally a mob of skaters and gazers. At one period it was calculated that there were not less than a hundred thousand persons upon this single sheet of ice.

The coachmen on the several roads, particularly on the western and northern roads, never remembered a severer frost than they experienced on the Sunday night just mentioned. Those who recollected that of 1814, when the Thames was frozen over, and booths raised on the ice, declared that they did not feel it so severely, as it did not come on so suddenly. The houses and trees in the country had a singular appearance on the Monday, owing to the combination of frost and fog; the trees, and fronts of houses, and even the glass was covered with thick white frost, and was no more transparent than ground-glass.

Butchers, in the suburbs, where the frost was felt more keenly than in the metropolis, were obliged to keep their shops shut in order to keep out the frost; many of them carried the meat into their parlours, and kept it folded up in cloths round the fires, and unfolded it as their customers came in and required it. The market gardeners also felt the severity of the weather—it stopped their labours, and some of the men, attended by their wives, went about in parties, and with frosted greens fixed at the tops of rakes and hoes, uttered the ancient cry of "Pray remember the gardeners! Remember the poor frozen out gardeners!"* [2]

The Apparition.

'Twas silence all, the rising moon

With clouds had veil'd her light,

The clock struck twelve, when, lo! I saw

A very chilling sight.Pale as a snow-ball was its face,

Like icicles its hair;

For mantle, it appeared to me

A sheet of ice to wear.Tho' seldom given to alarm,

I'faith, I'll not dissemble,

My teeth all chatter'd in my head,

And every joint did tremble.At last, I cried, "Pray who are you,

And whither do you go?"

Methought the phantom thus replied,

"My name is Sally Snow;"My father is the Northern Wind,

My mother's name was Water;

Old parson Winter married them,

And I'm their hopeful Daughter.I have a lover—Jackey Frost,

My dad the match condemns;

I've run from home to-night to meet

My love upon the Thames."I stopp'd Miss Snow in her discourse,

This answer just to cast in,

"I hope, if John and you unite,

Your union wo'n't be lasting!"Besides, if you should marry him,

But ill you'd do, that I know;

For surely Jackey Frost must be

A very slippery fellow."She sat her down before the fire,

My wonder now increases;

For she I took to be a maid,

Then tumbled into pieces!For air, thin air, did Hamlet's ghost,

His foremost cock-crow barter;

But what I saw, and now describe,

Resolv'd itself to water.GREAT FROST, 1814.

The severest and most remarkable frost in England of late years, commenced in December, 1813, and generally called "the Great Frost in 1814," was preceded by a great fog, which came on with the evening of the 27th of December, 1813. It is described as a darkness that might be felt. Cabinet business of great importance had been transacted, and lord Castlereagh left London about two hours before, to embark for the continent. The prince regent, (since George IV.) proceeding towards Hatfield on a visit to the marquis of Salisbury, was obliged to return to Carlton-house, after being absent several hours, during which period the carriages had not reached beyond Kentish-town, and one of the outriders fell into a ditch. Mr. Croker, secretary of the admiralty, on a visit northward, wandered likewise several hours in making a progress not more than three or four miles, and was likewise compelled to put back. It was "darkness that might be felt."

On most of the roads, excepting the high North-road, travelling was performed with the utmost danger, and the mails were greatly impeded.

On the 28th, the Maidenhead coach coming to London, missed the road near Hartford bridge and was overturned. Lord Hawarden was among the passengers, and severely injured.

On the 29th, the Birmingham mail was nearly seven hours in going from the Post-office to a mile or two below Uxbridge, a distance of twenty miles only: and on this, and other evenings, the short stages in the neighbourhood of London had two persons with links, running by the horses' heads. Pedestrians carried links or lanterns, and many, who were not so provided, lost themselves in the most frequented, and at other times well-known streets. Hackney-coachmen mistook the pathway for the road, and the greatest confusion prevailed.

On the 31st, the increased fog in the metropolis was, at night, truly alarming. It required great attention and thorough knowledge of the public streets to proceed any distance, and persons who had material business to transact were unavoidably compelled to carry torches. The lamps appeared through the haze like small candles. Careful hackney-coachmen got off the box and led their horses, while others drove only at a walking pace. There were frequent meetings of carriages, and great mischief ensued. Foot passengers, alarmed at the idea of being run down, exclaimed, "Who is coming?"—"Mind!"—"Take care!" &c. Females who ventured abroad were in great peril; and innumerable people lost their way.

After the fogs, there were heavier falls of snow than had been within the memory of man. With only short intervals, it snowed incessantly for forty-eight hours, and this after the ground was covered with ice, the result of nearly four weeks continued frost. During this long period, the wind blew almost continually from the north and north-east, and the cold was intense. A short thaw of about one day, rendered the streets almost impassable. The mass of snow and water was so thick, that hackney-coaches with an additional horse, and other vehicles, could scarcely plough their way through. Trade and calling of all kinds in the streets were nearly stopped, and considerably increased the distresses of the industrious. Few carriages, even stages, could travel the roads, and those in the neighbourhood of London seemed deserted. From many buildings, icicles, a yard and a half long, were seen suspended. The water-pipes to the houses were all frozen, and it became necessary to have plugs in the streets for the supply of all ranks of inhabitants. The Thames, from London Bridge to Blackfriars, was completely blocked up at ebb-tide for nearly a fortnight. Every pond and river near the metropolis was completely frozen.

Skating was pursued with great avidity on the Canal in St. James's, and the Serpentine in Hyde-park. On Monday the 10th of January, the Canal and the Basin in the Green-park were conspicuous for the number of skaters, who administered to the pleasure of the throngs on the banks; some by the agility and grace of their evolutions, and others by tumbles and whimsical accidents from clumsy attempts. A motley collection of all orders seemed eager candidates for applause. The sweep, the dustman, the drummer, the beau, gave evidence of his own good opinion, and claimed that of the belles who viewed his movements. In Hyde-park, a more distinguished order of visitors crowded the banks of the Serpentine. Ladies, in robes of the richest fur, bid defiance to the wintry winds, and ventured on the frail surface. Skaters, in great numbers, of first-rate notoriety, executed some of the most difficult movements of the art, to universal admiration. A lady and two officers, who performed a reel with a precision scarcely conceivable, received applause so boisterous as to terrify the fair cause of the general expression, and occasion her to forego the pleasure she received from the amusement. Two accidents occurred: a skating lady dislocated the patella or kneepan, and five gentlemen and a lady were submerged in the frosty fluid, but with no other injury than from the natural effect of so cold an embrace.

On the 20th, in consequence of the great accumulation of snow in London, it became necessary to relieve the roofs of the houses by throwing off the load collected upon them. By this means the carriage-ways in the middle of the streets were rendered scarcely passable; and the streams constantly flowing from the open plugs, added to the general mass of ice.

Many coach proprietors, on the northern and western roads, discontinued to run their coaches. In places where the roads were low, the snow had drifted above carriage height. On Finchley-common, by the fall of one night, it lay to a depth of sixteen feet, and the road was impassable even to oxen. On Bagshot-heath and about Esher and Cobham the road was completely choked up. Except the Kent and Essex roads, no others were passable beyond a few miles from London. The coaches of the western road remained stationary at different parts. The Windsor coach was worked through the snow at Conbrook, which was there sixteen feet deep, by employing about fifty labourers. At Maidenhead-lane, the snow was still deeper; and between Twyford and Reading it assumed a mountainous appearance. Accounts say that, on parts of Bagshot-heath, description would fail to convey and adequate idea of its situation. The Newcastle coach went off the road into a pit upwards of eight feet deep, but without mischief to either man or horse. The middle North-road was impassable at Highgate-hill.

On the 22d of January, and for some time afterwards, the ice on the Serpentine in Hyde-park bore a singular appearance, from mountains of snow which sweepers had collected together in different situations. The spaces allotted for the skaters were in circles, squares, and oblongs. Next to the carriage ride on the north side, many astonishing evolutions were performed by the skaters. Skipping on skates, and the Turk-cap backwards, were among the most conspicuous. the ice, injured by a partial thaw in some places, was much cut up, yet elegantly dressed females dashed between the hillocks of snow, with great bravery.

At this time the appearance of the river Thames was most remarkable. Vast pieces of floating ice, laden generally with heaps of snow, were slowly carried up and down by the tide, or collected where the projecting banks or the bridges resisted the flow. These accumulations sometimes formed a chain of glaciers, which, uniting at one moment, were at another cracking and bounding against each other in a singular and awful manner with loud noise. Sometimes these ice islands rose one over another, covered with angry foam, and were violently impelled by the winds and waves through the arches of the bridges, with tremendous crashes. Near the bridges, the floating pieces collected about mid-water, or while the tide was less forcible, and ranged themselves on each other; the stream formed them into order by its force as it passed, till the narrowness of the channel increased the power of the flood, when a sudden disruption taking place, the masses burst away, and floated off. The river was frozen over for the space of a week, and a complete Frost Fair held upon it, as will be mentioned presently.

Since the establishment of mail-coaches correspondence had not been so interrupted as on this occasion. Internal communication was completely at a stand till the roads could be in some degree cleared. The entire face of the country was one uniform sheet of snow; no trace of road was discoverable.

The Post-office exerted itself to have the roads cleared for the conveyance of the mails, and the government interfered by issuing instructions to every parish in the kingdom to employ labourers in reopening the ways.

In the midland counties, particularly on the borders of Northamptonshire and Warwickshire, the snow lay to a height altogether unprecedented. At Dunchurch, a small village on the road to Birmingham, through Coventry, and for a few miles round that place, in all directions, the drifts exceeded twenty-four feet, and no tracks of carriages or travellers could be discovered, except on the great road, for many days.

The Cambridge mail coach coming to London, sunk into a hollow of the road, and remained with the snow drifting over it, from one o'clock to nine in the morning, when it was dragged out by fourteen waggon horses. The passengers, who were in the coach the whole of the time, were nearly frozen to death.

On the 26th, the wind veered to the south-west, and a thaw was speedily discernible. The great fall of the Thames at London-bridge for some days presented a scene both novel and interesting. At the ebbing of the tide, huge fragments of ice were precipitated down the stream with great violence, accompanied by a noise, equal to the report of a small piece of artillery. On the return of the tide, they were forced back; but the obstacles opposed to their passage through the arches were so great, as to threaten a total stoppage to the navigation of the river. The thaw continued, and these appearances gradually ceased.

On the 27th, 28th, and 29th, the roads and streets were nearly impassable from floods, and the accumulation of snow. On Sunday the 30th a sharp frost set in, and continued till the following Saturday evening, the 5th of February.

The Falmouth mail coach started from thence for Exeter, after having proceeded a few miles was overturned, without material injury to the passengers. With the assistance of an additional pair of horses it reached the first stage; after which all endeavours to proceed were found perfectly useless, and the letters were sent to Bodmin by the guard on horseback. The Falmouth and Plymouth coach and its passengers were obliged to remain at St. Austell.

At Plymouth, the snow was nearly four feet high in several of the streets.

At Liverpool, on the 17th of January, Fahrenheit's thermometer, in the Athenæum, stood at fifteen degrees; seven below the freezing point. From the ice accumulated in the Mersey, boats could not pass over. Almost all labour without doors was at a stand.

At Gloucester, Jan. 17. The severity of the frost had not been exceeded by any that preceded it. The Severn was frozen over, and people went to Tewkesbury market across the ice on horseback. The cold was intense. The thermometer, exposed in a north-eastern aspect, stood at thirteen degrees, nine below the freezing point. On the eastern coast, it stood as low as nine and ten; a degree of cold unusual in this country.

Bristol, Jan. 18. The frost continued in this city with the like severity. The Floating Harbour from Cumberland basin to the Feeder, at the bottom of Avon-street, was one continued sheet of ice; and for the first time in the memory of man, the skater made his appearance under Bristol-bridge. The Severn was frozen over at various points, so as to bear the weight of passengers.

At Whitehaven, Jan. 18, the frost had increased in severity. All the ponds and streams were frozen; and there was scarcely a pump in the town that gave out water. The market was very thinly attended, it having been found in many parts impossible to travel until the snow was cut.

At Dublin, Jan. 14, the snow lay in a quantity unparalleled for half a century. In the course of one day and night, it descended so inconceivably thick and rapid, as to block up all the roads, and preclude the possibility of the mail coaches being able to proceed, and it was even found impracticable to send the mails on horseback. Thus all intercourse with the interior was cut off, and it was not until the 18th, when an intense frost suddenly commenced, that the communication was opened, and several mail bags arrived from the country on horseback.

The snow in many of the narrow streets of Dublin, after the footways had been in some measure cleared, was more than six feet. It was nearly impossible for any carriage to force a passage, and few ventured on the hazardous attempt. Accidents, both distressing and fatal, occurred. In several streets and lanes the poorer inhabitants were literally blocked up in their houses, and in the attempt to go abroad, experienced every kind of misery. The number of deaths from cold and distress were greater than at any other period, unless at the time of the plague. There were eighty funerals on the Sunday before this date. The coffin-makers in Cook-street could with difficulty complete their numerous orders: and not a few poor people lay dead in their wretched rooms for several days, from the impossibility of procuring assistance to convey them to the Hospital-fields, and the great difficulty and danger of attempting to open the ground, which was very uneven, and where the snow remained in some parts, twenty feet deep.

From Canterbury, January 25, the communication with the metropolis was not open from Monday until Saturday preceding this date, when the snow was cut through by the military at Chatham-hill, and near Gravesend; and the stages proceeded with their passengers. The mail of the Thursday night arrived at Canterbury late on Friday evening, the bags having been conveyed part of the distance upon men's shoulders. The bags of Friday and Saturday night arrived together on Sunday morning about ten o'clock.

Dalrymple, North Britain, January 29.—Wednesday, the 26th, was an epoch ever to be remembered by the inhabitants of this village. The thaw of that and the preceding day had opened the Doon, formerly "bound like a rock," to a considerable distance above this; and the melting of the snow on the adjacent hills swelled the river beyond its usual height, and burst up vast fragments of ice and congealed snow. It forced them forward with irresistible impetuosity, bending trees like willows, carrying down Skelton-bridge, and sweeping all before it. The overwhelming torrent in its awful progress accumulated a prodigious mass of the frozen element, which, as if in wanton frolic, it heaved out into the field on both sides, covering acres of ground many feet deep. Alternately loading and discharging in this manner, it came to a door or two in the village, as if to apprize the inhabitants of its powers. The river having deserted its wonted channel, endeavoured to make its grand entry by several courses successively in Saint Valley, and finding no one of them sufficient for its reception, took them altogether, and overrunning the whole holm at once, appeared here in terrific grandeur, between seven and eight o'clock in the evening, when the moon retreated behind a cloud, and the gloom of night added to the horrors of the tremendous scene. Like a sea, it overflowed all the gardens on the east side, from the cross to the bridge, and invaded the houses behind by the doors and windows, extinguishing the fires in a moment, lifting and tumbling the furniture, and gushing out at the front doors with incredible rapidity. Its principal inroad was by the end of a bridge. Here, while the houses stood as a bank on either side, it came crashing and roaring up the street in full career, casting forth, within a few yards of the cross, floats of ice like millstones. The houses on the west side were in the same situation with those on the east. At one place the water was running on the house-eaves, at another it was near the door-head, and midway up the street, it stood three feet and a half above the door. Had it advanced five minutes longer in this direction, the whole village must have been inundated.

During this frost a great number of the fish called golden maids, were picked up on Brighton beach and sold at good prices. They floated ashore quite blind, having been reduced to that state by the snow.

Annexed are a few of the casualties consequent on this great frost. A woman was found frozen to death on the Highgate-road. She proved to have been a charwoman, returning from Highgate, where she had been at work, to Pancras.

A poor woman named Wood, while crossing Blackheath from Leigh to the village of Charlton, accompanied by her two children, was benighted, and missed her way. After various efforts to extricate herself, she fell into a hole, and was nearly buried in the snow. From this, however, she contrived to escape, and again proceeded; but at length, being completely exhausted, and her children benumbed with cold, she sat down on the trunk of a tree, where, wrapping her children in her cloak, she endeavoured by loud cries to attract the attention of some passengers. Her shrieks at length were heard by a waggoner, who humanely waded through the snow to her assistance, and taking her children, who seemed in a torpid state, in his arms, he conducted her to a public-house; one of the infants was frozen to death, and the other was recovered with extreme difficulty.

As some workmen were clearing away the snow, which was twelve feet deep, at Kipton, on the border of Northamptonshire, the body of a child about three years old was discovered, and immediately afterwards the body of its mother. She was the wife of a soldier of the 16th regiment, returning home with her infant after accompanying her husband to the place of embarkation. It was supposed they had been a week in the snow.

There was found lying in the road leading from Longford to Upham, frozen to death, a Mr. Apthorne, a grazier, at Coltsworth. He had left Hounslow at dusk on Monday evening, after having drank rather freely, and proposed to go that night to Marlow.

On his return from Wakefield market, Mr. Husband, of Holroyd Hall, was frozen to death, within little more than a hundred yards of the house of his nephew, with whom he resided.

Mr. Chapman, organist, and master of the central school at Andover, Hants, was frozen to death near Wallop, in that county.

A young man named Monk, while driving a stage-coach near Ryegate, was thrown off the box on a lump of frozen snow, and killed on the spot.

The thermometer during this intense frost was as low as 7° and 8° of Fahrenheit, in the neighbourhood of London. There are instances of its having been lower in many seasons, but so long a continuance of very cold weather was never experienced in this climate within the memory of man.

Frost Fair—1814.

On Sunday, the 30th of January, the immense masses of ice that floated from the upper parts of the river, in consequence of the thaw on the two preceding days, blocked up the Thames between Blackfriars and London Bridges; and afforded every probability of its being frozen over in a day or two. Some adventurous persons even now walked on different parts, and on the next day, Monday the 31st, the expectation was realized. During the whole of the afternoon, hundreds of people were assembled on Blackfriars and London Bridges, to see people cross and recross the Thames on the ice. At one time seventy persons were counted walking from Queenhithe to the opposite shore. The frost of Sunday night so united the vast mass as to render it immovable by the tide.

On Tuesday, February 1, the river presented a thoroughly solid surface over that part which extends from Blackfriars Bridge to some distance below Three Crane Stairs, at the bottom of Queen-street, Cheapside. The watermen placed notices at the end of all the streets leading to the city side of the river, announcing a safe footway over, which attracted immense crowds, and in a short time thousands perambulated the rugged plain, where a variety of amusements were provided. Among the more curious of these was the ceremony of roasting a small sheep, or rather toasting or burning it over a coal fire, placed in a large iron pan. For a view of the extraordinary spectacle, sixpence was demanded, and willingly paid. The delicate meat, when done, was sold at a shilling a slice, and termed "Lapland mutton." There were a great number of booths ornamented with streamers, flags, and signs, and within them there was a plentiful store of favourite luxuries with most of the multitude, gin, beer, and gingerbread. The thoroughfare opposite Three Crane Stairs was complete and well frequented. It was strewed with ashes, and afforded a very safe, although a very rough path. Near Blackfriars Bridge, however, the way was not equally severe; a plumber, named Davis, having imprudently ventured to cross with some lead in his hands, sank between two masses of ice, and rose no more. Two young women nearly shared a similar fate; they were rescued from their perilous situation by the prompt efforts of two watermen. Many a fair nymph indeed was embraced in the icy arms of old Father Thames;—three young quakeresses had a sort of semi-bathing, near London Bridge, and when landed on terra-firma; made the best of their way through the Borough, amidst the shouts of an admiring populace. From the entire obstruction the tide did not appear to ebb for some days more than one half the usual mark.

On Wednesday, Feb. 2, the sports were repeated, and the Thames presented a complete "FROST FAIR." The grand "mall" or walk now extended from Blackfriars Bridge to London Bridge; this was named the "City-road," and was lined on each side by persons of all descriptions. Eight or ten printing presses were erected and numerous pieces commemorative of [t]he "great frost" were printed on the ice. Some of these frosty typographers displayed considerable taste in their specimens. At one of the presses, an orange-coloured standard was hoisted, with the watch-word "ORANGE BOVEN," in large characters. This was in allusion to the recent restoration of Holland, which had been for several years under the dominion of the French. From this press the following papers were issued.

"FROST FAIR.

"Amidst the arts which on the THAMES appear,

To tell the wonders of this icy year,

PRINTING claims prior place, which at one view

Erects a monument of THAT and YOU."Another:

"You that walk here, and do design to tell

Your children's children what this year befell,

Come, buy this print, and it will then be seen

That such a year as this has seldom been."Another of these stainers of paper addressed the spectators in the following terms: "Friends, now is your time to support the freedom of the press. Can the press have greater liberty? here you find it working in the middle of the Thames; and if you encourage us by buying our impressions, we will keep it going in the true spirit of liberty during the frost." One of the articles printed and sold contained the following lines:

"Behold, the river Thames is frozen o'er,

Which lately ships of mighty burden bore;

Now different arts and pastimes here you see,

But printing claims the superiority."The Lord's prayer and several other pieces were issued from the icy printing offices, and bought with the greatest avidity.

On Thursday, Feb. 3, the number of adventurers increased. Swings, book-stalls, dancing in a barge, suttling-booths, playing at skittles, and almost every appendage of a fair on land, appeared now on the Thames. Thousands flocked to this singular spectacle of sports and pastimes. The ice seemed to be a solid rock, and presented a truly picturesque appearance. The view of St. Paul's and of the city with the white foreground had a very singular effect;—in many parts, mountains of ice upheaved resembled the rude interior of a stone quarry.

Friday, Feb. 4. Each day brought a fresh accession of "pedlars to sell their wares;" and the greatest rubbish of all sorts was raked up and sold at double and treble the original cost. Books and toys, labelled "bought on the Thames," were in profusion. The watermen profited exceedingly, for each person paid a toll of twopence or threepence before he was admitted to "Frost Fair;" some douceur was expected on the return. Some of them were said to have taken six pounds each in the course of a day.

This afternoon, about five o'clock, three persons, an old man and two lads, were on a piece of ice above London-bridge, which suddenly detached itself from the main body, and was carried by the tide through one of the arches. They laid themselves down for safety, and the boatmen at Billingsgate, put off to their assistance, and rescued them from their impending danger. One of them was able to walk, but the other two were carried, in a state of insensibility, to a public-house, where they received every attention their situation required.

Many persons were on the ice till late at night, and the effect by moonlight was singularly novel and beautiful. The bosom of the Thames seemed to rival the frozen climes of the north.

Saturday, Feb. 5. This morning augured unfavourably for the continuance of "FROST FAIR." The wind had veered to the south, and there was a light fall of snow. The visitors, however, were not to be deterred by trifles. Thousands again ventured, and there was still much life and bustle on the frozen element; the footpath in the centre of the river was hard and secure, and among the pedestrians were four donkies; they trotted a nimble pace, and produced considerable merriment. At every glance, there was a novelty of some kind or other. Gaming was carried on in all its branches. Many of the itinerant admirers of the profits gained by E O Tables, Rouge et Noir, Te-totum, wheel of fortune, the garter, &c. were industrious in their avocations, and some of their customers left the lures without a penny to pay the passage over a plank to the shore. Skittles was played by several parties, and the drinking tents were filled by females and their companions, dancing reels to the sound of fiddles, while others sat round large fires, drinking rum, grog, and other spirits. Tea, coffeee, and eatables, were provided in abundance, and passengers were invited to eat by way of recording their visit. Several tradesmen, who at other times were deemed respectable, attended with their wares, and sold books, toys, and trinkets of almost every description.

Towards the evening, the concourse thinned; rain began to fall, and the ice to crack, and on a sudden it floated with the printing presses, booths, and merry-makers, to the no small dismay of publicans, typographers, shopkeepers, and sojourners.

A short time previous to the general dissolution, a person near one of the printing presses, handed the following jeu d'esprit to its conductor; requesting that it might be printed on the Thames.

To Madam Tabitha Thaw.

"Dear dissolving dame,

"FATHER FROST and SISTER SNOW have Boneyed my borders, formed an idol of ice upon my bosom, and all the LADS OF LONDON come to make merry: now as you love mischief, treat the multitude with a few CRACKS by a sudden visit, and obtain the prayers of the poor upon both banks. Given at my own press, the 5th Feb. 1814.

THOMAS THAMES."

The thaw advanced more rapidly than indiscretion and heedlessness retreated. Two genteel-looking young men ventured on the ice above Westminster Bridge, notwithstanding the warnings of the watermen. A large mass on which they stood, and which had been loosened by the flood tide, gave way, and they floated down the stream. As they passed under Westminster Bridge they cried piteously for help. They had not gone far before they sat down, near the edge; this overbalanced the mass, they were precipitated into the flood, and overwhelmed for ever.

A publican named Lawrence, of the Feathers, in High Timber-street, Queenhithe, erected a booth on the Thames opposite Brook's-wharf, for the accomodation of the curious. At nine at night he left it in the care of two men, taking away all the liquors, except some gin, which he gave them for their own use.—

Sunday, Feb. 6. At two o'clock this morning, the tide began to flow with great rapidity at London Bridge; the thaw assisted the efforts of the tide, and the booth last mentioned was violently hurried towards Blackfriars Bridge. There were nine men in it, but in their alarm they neglected the fire and candles, which communicating with the covering, set it in a flame. They succeeded in getting into a lighter which had broken from its moorings. In this vessel they were wrecked, for it was dashed to pieces against one of the piers of Blackfriars Bridge: seven of them got on the pier and were taken off safely; the other two got into a barge while passing Puddle-dock.

On this day, the Thames towards high tide (about 3 p.m.) presented a miniature idea of the Frozen Ocean; the masses of ice floating along, added to the great height of the water, formed a striking scene for contemplation. Thousands of disappointed persons thronged the banks; and many a 'prentice, and servant maid, "sighed unutterable things," at the sudden and unlooked for destruction of "FROST FAIR."

Monday, Feb. 7. Immense fragments of ice yet floated, and numerous lighters, broken from their moorings, drifted in different parts of the river; many of them were complete wrecks. The frozen element soon attained its wonted fluidity, and old Father Thames looked as cheerful and as busy as ever.

The severest English winter, however astonishing to ourselves, presents no views comparable to the winter scenery of more northern countries. A philosopher and poet of our own days, who has been also a traveller, beautifully describes a lake in Germany:—

Christmas out of doors at Ratzburg.

By S. T. COLERIDGE, Esq.

The whole lake is at this time one mass of thick transparent ice, a spotless mirror of nine miles in extent! The lowness of the hills, which rise from the shores of the lake, preclude the awful sublimity of Alpine scenery, yet compensate for the want of it, by beauties of which this very lowness is a necessary condition. Yesterday I saw the lesser lake completely hidden by mist; but the moment the sun peeped over the hill, the mist broke in the middle, and in a few seconds stood divided, leaving a broad road all across the lake; and between these two walls of mist the sunlight burnt upon the ice, forming a road of goden fire, intolerably bright! and the mist walls themselves partook of the blaze in a multitude of shining colours. This is our second post. About a month ago, before the thaw came on, there was a storm of wind; during the whole night, such were the thunders and howlings of the breaking ice, that they have left a conviction on my mind, that there are sounds more sublime than any sight can be, more absolutely suspending the power of comparison, and more utterly absorbing the mind's self-consciousness in its total attention to the object working upon it. Part of the ice, which the vehemence of the wind had shattered, was droven shoreward, and froze anew. On the evening of the next day at sunset, the shattered ice thus frozen appeared of a deep blue, and in shape like an agitated sea; beyond this, the water that ran up between the great islands of ice which had preserved their masses entire and smooth, shone of a yellow green; but all these scattered ice islands themselves were of an intensely bright blood colour—they seemed blood and light in union! On some of the largest of these islands, the fishermen stood pulling out their immense nets through the holes made in the ice for this purpose, and the men, their net poles, and their huge nets, were a part of the glory—say rather, it appeared as if the rich crimson light had shaped itself into these forms, figures, and attitudes, to make a glorious vision in mockery of earthly things.

The lower lake is now all alive with skaters and with ladies driven onward by them in their ice cars. Mercury surely was the first maker of skates, and the wings at his feet are symbols of the invention. In skating, there are three pleasing circumstances—the infinitely subtle particles of ice which the skaters cut up, and which creep and run before the skate like a low mist and in sunrise or sunset become coloured; second, the shadow of the skater in the water, seen through the transparent ice; and third, the melancholy undulating sound from the skate not without variety; and when very many are skating together, the sounds and the noises give an impulse to the icy trees, and the woods all round the lake trinkle.

In the frosty season when the sun

Was set, and visible for many a mile,

The cottage windows through the twilight blazed,

I heeded not the summons;—happy time

It was indeed for all of us, to me

It was a time of rapture! clear and loud

The village clock tolled six! I wheel'd about

Proud and exulting, like an untired horse

That cared not for its home. All shod with steel

We hissed along the polished ice, in games

Confederate, imitative of the chase

And woodland pleasures, the resounding horn,

The pack loud bellowing and the hunted hare.

So through the darkness and the cold we flew,

And not a voice was idle; with the din,

Meanwhile the precipices rang aloud,

The leafless trees and every icy crag

Tinkled like iron, while the distant hills

Into the tumult sent an alien sound

Of melancholy—not unnoticed, while the stars

Eastward, were sparkling clear, and in the west

The orange sky of evening died away.Not seldom from the uproar I retired

Into a silent bay, or sportively

Glanced sideway, leaving the tumultuous throng

To cut across the image of a star

That gleamed upon the ice; and oftentimes

Where we had given our bodies to the wind,

And all the shadowy banks on either side

Came sweeping through the darkness, shunning still

The rapid line of motion, then at once

Have I, reclining back upon my heels,

Stopped short; yet still the solitary cliffs

Wheeled by me even as if the earth had rolled

With visible motion her diurnal round!

Behind me did they stretch in solemn train

Feebler and feebler, and I stood and watched

Till all was tranquil as a summer sea.Wordsworth.

Skating.

The earliest notice of skating in England is obtained from the earliest description of London. Its historian relates that, "when the great fenne or moore (which watereth the walles of the citie on the north side) is frozen, many young men play upon the yce." Happily, and probably for want of a term to call it by, he describes so much of this pastime in Moorfields, as acquaints us with their mode of skating: "Some," he says, "stryding as wide as they may, doe slide swiftly," this then is sliding; but he proceeds to tell us, that "some tye bones to their feet, and under their heeles, and shoving themselves by a little picked staffe doe slide as swiftly as a birde flyeth in the air, or an arrow out of a crosse-bow."* [3] Here, although the implements were rude, we have skaters; and it seems that one of their sports was for two to start a great way off opposite to each other, and when they met, to lift their poles and strike each other, when one or both fell, and were carried to a distance from each other by the celerity of their motion. Of the present wooden skates, shod with iron, there is no doubt, we obtained a knowledge from Holland.

The icelanders also used the shank-bone of a deer or sheep about a foot long, which they creased, because they should not be stopped by drops of water upon them.† [4]

It is asserted in the "Encyclopædia Britannica," that Edinburgh produced more instances of elegant skaters than perhaps any other country, and that the insitution of a skating club there contributed to its improvement. "I have however seen, some years back" says Mr. Strutt, "when the Serpentine river was frozen over, four gentlemen there dance, if I may be allowed the expression, a double minuet in skates with as much ease, and I think more elegance, than in a ball room; others again, by turning and winding with much adroitness, have readily in succession described upon the ice the form of all the letters in the alphabet." The same may be observed there during every frost, but the elegance of skaters on that sheet of water is chiefly exhibited in quadrilles, which some parties go through with a beauty scarcely imaginable by those who have not seen graceful skating. In variety of attitude, and rapidity of movement, the Dutch, who, of necessity, journey long distances on their rivers and canals, are greatly our superiors.

NATURALISTS' CALENDAR.

Mean Temperature . . . 36 . 35.