December 25.

The Nativity of Christ, or Christmas-day. St. Anastasia, A. D. 304. Another St. Anastasia. St. Eugenia, A. D. 257.

Christmas-day.The festival of the nativity was anciently kept by different churches in April, May, and in this month. It is now kept on this day by every established church of christian denomination; and is a holiday all over England, observed by the suspension of all public and private business, and the congregating of friends and relations for "comfort and joy."

Our countryman, Barnaby Googe, from the Latin of Naogeorgus, gives us some lines descriptive of the old festival:—

Then comes the day wherein the Lorde

did bring his birth to passe;

Whereas at midnight up they rise,

and every man to Masse.

This time so holy counted is,

that divers earnestly

Do thinke the waters all to wine

are chaunged sodainly;

In that same houre that Christ himselfe

was borne, and came to light,

And unto water streight againe

transformde and altred quight.

There are beside that mindfully

the money still do watch,

That first to aultar commes, which then

they privily do snatch.

The priestes, least other should it have,

takes oft the same away,

Whereby they thinke throughout the yeare

to have good lucke in play,

And not to lose: then straight at game

till day-light do they strive,

To make some present proofe how well

their hallowde pence wil thrive.

Three Masses every priest doth sing,

upon that solemne day,

With offrings unto every one,

that so the more may play.

This done, a woodden child in clowtes

is on the aultar set,

About the which both boyes and gyrles

do daunce and trymly jet,

And Carrols sing in prayse of Christ,

and, for to helpe them heare,

The organs aunswere every verse

with sweete and solemne cheare.

The priestes doe rore aloude; and round

about the parentes stande

To see the sport, and with their voyce

do helpe them and their hande.

The commemorations in our own times vary from the account in these versifyings. An accurate observer, with a hand powerful to seize, and a hand skilled in preserving manners, offers us a beautiful sketch of Christmas-tide in the "New Monthly Magazine," of December 1, 1825. Foremost in his picture is the most estimable, because the most useful and ornamental character in society,—a good parish priest.

"Our pastor was told one day, in argument, that the interests of christianity were opposed to universal enlightenment. I shall not easily forget his answer. 'The interests of christianity,' said he, 'are the same as the interests of society. It has no other meaning. Christianity is that very enlightenment you speak of. Let any man find out that thing, whatever it be, which is to perform the very greatest good to society, even to its own apparent detriment, and I say that is christianity, or I know not the spirit of its founder. What?' continued he, 'shall we take christianity for an arithmetical puzzle, or a contradiction in terms, or the bitterness of a bad argument, or the interests, real or supposed, of any particular set of men? God forbid. I wish to speak with reverence (this conclusion struck me very much)—I wish to speak with reverence of whatever has taken place in the order of Providence. I wish to think the best of the very evils that have happened; that a good has been got out of them; perhaps that they were even necessary to the good. But when once we have attained better means, and the others are dreaded by the benevolent, and scorned by the wise, then is the time come for throwing open the doors to all kindliness and to all knowledge, and the end of christianity is attained in the reign of beneficence.'

"In this spirit our pastor preaches to us always, but most particularly on Christmas-day; when he takes occasion to enlarge on the character and views of the divine person who is supposed then to have been born, and sends us home more than usually rejoicing. On the north side of the church at M. are a great many holly-trees. It is from these that our dining and bed-rooms are furnished with boughs. Families take it by turns to entertain their friends. They meet early; the beef and pudding are noble; the mince-pies—peculiar; the nuts half play-things and half-eatables; the oranges as cold and acid as they ought to be, furnishing us with a superfluity which we can afford to laugh at; the cakes indestructible; the wassail bowls generous, old English, huge, demanding ladles, threatening overflow as they come in, solid with roasted apples when set down. Towards bed-time you hear of elder-wine, and not seldom of punch. At the manor-house it is pretty much the same as elsewhere. Girls, although they be ladies, are kissed under the misletoe. If any family among us happen to have hit upon an exquisite brewing, they send some of it round about, the squire's house included; and he does the same by the rest. Riddles, hot-cockles, forfeits, music, dances sudden and not to be suppressed, prevail among great and small; and from two o'clock in the day to midnight, M. looks like a deserted place out of doors, but is full of life and merriment within. Playing at knights and ladies last year, a jade of a charming creature must needs send me out for a piece of ice to put in her wine. It was evening and a hard frost. I shall never forget the cold, cutting, dreary, dead look of every thing out of doors, with a wind through the wiry trees, and snow on the ground, contrasted with the sudden return to warmth, light, and joviality.

"I remember we had a discussion that time, as to what was the great point and crowning glory of Christmas. Many were for mince-pie; some for the beef and plum-pudding; more for the wassail-bowl; a maiden lady timidly said, the misletoe; but we agreed at last, that although all these were prodigious, and some of them exclusively belonging to the season, the fire was the great indispensable. Upon which we all turned our faces towards it, and began warming our already scorched hands. A great blazing fire, too big, is the visible heart and soul of Christmas. You may do without beef and plum-pudding; even the absence of mince-pie may be tolerated; there must be a bowl, poetically speaking, but it need not be absolutely wassail. The bowl may give place to the bottle. But a huge, heaped-up, over heaped-up, all-attracting fire, with a semicircle of faces about it, is not to be denied us. It is the lar and genius of the meeting; the proof positive of the season; the representative of all our warm emotions and bright thoughts; the glorious eye of the room; the inciter to mirth, yet the retainer of order; the amalgamater of the age and sex; the universal relish. Tastes may differ even on a mince-pie; but who gainsays a fire? The absence of other luxuries still leaves you in possession of that; but

'Who can hold a fire in his hand

With thinking on the frostiest twelfth-cake?'"Let me have a dinner of some sort, no matter what, and then give me my fire, and my friends, the humblest glass of wine, and a few penn'orths of chesnuts, and I will still make out my Christmas. What! Have we not Burgundy in our blood? Have we not joke, laughter, repartee, bright eyes, comedies of other people, and comedies of our own; songs, memories, hopes? [An organ strikes up in the street at this word, as if to answer me in the affirmative. Right, thou old spirit of harmony, wandering about in the ark of thine, and touching the public ear with sweetness and an abstraction! Let the multitude bustle on, but not unarrested by thee and by others, and not unreminded of the happiness of renewing a wise childhood.] As to our old friends the chesnuts, if any body wants an excuse to his dignity for roasting them, let him take the authority of Milton. 'Who now,' says he, lamenting the loss of his friend Deodati,—'who now will help to soothe my cares for me, and make the long night seem short with his conversation; while the roasting pear hisses tenderly on the fire, and the nuts burst away with a noise,—

'And out of doors a washing storm o'erwhelms

Nature pitch-dark, and rides the thundering elms?'

Christmas in France.

From a newspaper of 1823, (the name unfortunately not noted at the time, and not immediately ascertainable), it appears that Christmas in France is another thing from Christmas in England.

"The habits and customs of the Parisians vary much from those of our own metropolis at all times, but at no time more than at this festive season. An Englishman in Paris, who had been for some time without referring to his almanac, would not know Christmas-day from another by the appearance of the capital. It is, indeed, set down as a jour de fete in the calendar, but all the ordinary business of life is transacted; the streets are, as usual, crowded with waggons and coaches; the shops, with few exceptions, are open, although on other fête days the order for closing them is rigorously enforced, and if not attended to, a fine levied; and at the churches nothing extraordinary is going forward. All this is surprising in a catholic country, which professes to pay such attention to the outward rites of religion.

"On Christmas-eve indeed, there is some bustle for a midnight mass, to which immense numbers flock, as the priests, on this occasion, get up a showy spectacle which rivals the theatres. The altars are dressed with flowers, and the churches decorated profusely; but there is little in all this to please men who have been accustomed to the John Bull mode of spending the evening. The good English habit of meeting together to forgive offences and injuries, and to cement reconciliations, is here unknown. The French listen to the church music, and to the singing of their choirs, which is generally excellent, but they know nothing of the origin of the day and of the duties which it imposes. The English residents in Paris, however, do not forget our mode of celebrating this day. Acts of charity from the rich to the needy, religious attendance at church, and a full observance of hospitable rites, are there witnessed. Paris furnishes all the requisites for a good pudding, and the turkeys are excellent, though the beef is not to be displayed as prize production.

"On Christmas-day all the English cooks in Paris are in full business. The queen of cooks, however, is Harriet Dunn, of the Boulevard.—As sir Astley Cooper among the cutters of limbs, and d'Egville among the cutters of capers, so is Harriet Dunn among the professors of one of the most necessary, and in its results, most gratifying professions of existence; her services are secured beforehand by special retainers; and happy is the peer who can point to his pudding, and declare that it is of the true "Dunn" composition. Her fame has even extended to the provinces. For some time previous to Christmas-day, she forwards puddings in cases to all parts of the country, ready cooked and fit for the table, after the necessary warming. All this is, of course, for the English. No prejudice can be stronger than that of the French against plum-pudding—a Frenchman will dress like an Englishman, swear like an Englishman, and get drunk like an Englishman; but if you would offend him for ever, compel him to eat plum-pudding. A few of the leading restauranteurs, wishing to appear extraordinary, have plomb-pooding upon their cartes, but in no instance is it ever ordered by a Frenchman. Every body has heard the story of St. Louis—Henri Quatre, or whoever else it might be, who, wishing to regale the English ambassador on Christmas-day with a plumb-pudding, procured an excellent recipe for making one, which he gave to his cook, with strict injunctions that it should be prepared with due attention to all the particulars. The weight of the ingredients, the size of the copper, the quantity of water, the duration of time, every thing was attended to except one trifle—the king forgot the cloth, and the pudding was served up like so much soup, in immense tureens, to the surprise of the ambassador, who was, however, too well bred to express his astonishment. Louis XVIII., either to show his contempt of the prejudices of his countrymen, or to keep up a custom which suits his palate, has always an enormous pudding on Christmas-day, the remains of which, when it leaves the table, he requires to be eaten by the servants, bon gré, mauvais gré; but in this instance even the commands of sovereignty are disregarded, except by the numerous English in his service, consisting of several valets, grooms, coachmen, &c., besides a great number of ladies' maids, in the service of the duchesses of Angouleme and Berri, who very frequently partake of the dainties of the king's table."

The following verses from the original in old Norman French, are said to be the first drinking song composed in England. They seem to be an abridged version of the Christmas carol in Anglo-Norman French, translated by Mr. Douce:—

Lordlings, from a distant home,

To seek old Christmas are we come,

Who loves our minstrelsy—

And here, unless report mis-say,

The greybeard dwells; and on this day

Keeps yearly wassel, ever gay

With festive mirth and glee.Lordlings, list, for we tell you true;

Christmas loves the jolly crew,

That cloudy care defy:

His liberal board is deftly spread,

With manchet loaves and wastel bread;

His guests with fish and flesh are led,

Nor lack the stately pye.Lordlings, it is our host's command,

And Christmas joins him hand in hand,

To drain the brimming bowl;

And I'll be foremost to obey—

Then pledge me, sirs, and drink away,

For Christmas revels here to-day

And sways without controul.

Now wassel to you all! and merry may you be,

And foul that wight befall, who drinks not health to me.

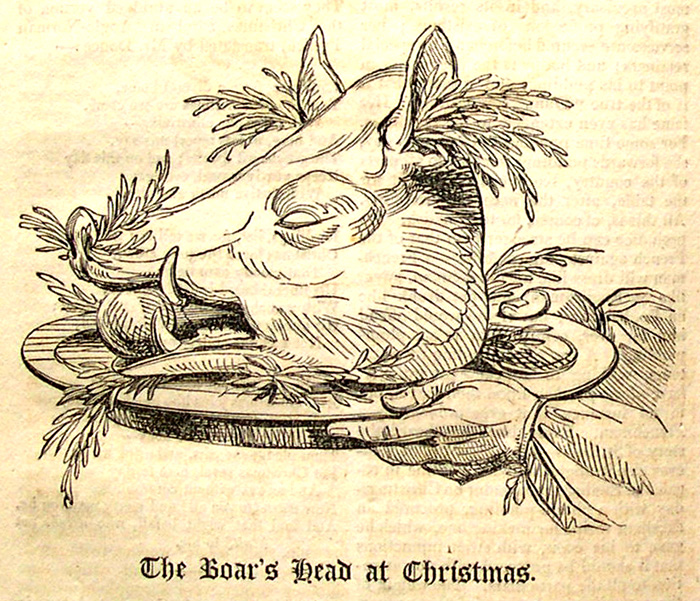

There were anciently great doings in the halls of the inns of court at Christmas time. At the Inner-Temple early in the morning, the gentlemen of the inn went to church, and after the service they did then "presently repair into the hall to breakfast with brawn, mustard, and malmsey." At the first course at dinner, was "served in, a fair and large Bore's head upon a silver platter with minstralsye."*[1]

The Boar's Head.

With our forefathers a soused boar's head was borne to the principal table in the hall with great state and solemnity, as the first dish on Christmas-day.

In the book of "Christmasse Carolles" printed by Wynkyn de Worde in 1521, are the words sung at this "chefe servyce," or on bringing in this the boar's head, with great ceremony, as the first dish: it is in the next column.

A CAROL bryngyng in the Boar's Head.

Caput Apri defero

Reddens laudes Domino.The bore's head in hande bring I,

With garlandes gay and rosemary,

I pray you all synge merely,

Qui estis in convivio.The bore's head, I understande,

Is the chefe servyce in this lande.

Loke wherever it be fande

Servite com Cantico.Be gladde, lords, both more and lasse,

For this hath ordayned our stewarde

To chere you all this Christmasse,

The bore's head with mustarde.

The Boar's Head at Christmas.

"With garlandes gay and rosemary."

Warton says, "This carol, yet with many innovations, is retained at Queen's-college, in Oxford." It is still sung in that college, somewhat altered, "to the common chant of the prose version of the psalms in cathedrals;" so, however, the rev. Mr. Dibdin says, as mentioned before.

Mr. Brand thinks it probable that Chaucer alluded to the custom of bearing the boar's head, in the following passage of the "Franklein's Tale:"—

"Janus sitteth by the fire with double berd,

And he drinketh of his bugle-horne the wine,

Before him standeth the brawne of the tusked swine."

In "The Wonderful Yeare, 1603," Dekker speaks of persons apprehensive of catching the plague, and says, "they went (most bitterly) miching and muffled up and down, with rue and wormwood stuft into their eares and nosthrils, looking like so many bores heads stuck with branches of rosemary, to be served in for brawne at Christmas."

Holinshed says, that in 1170, upon the young prince's coronation, king Henry II. "served his son at the table as sewer, bringing up the bore's head, with trumpets before it, according to the manner."*[2]

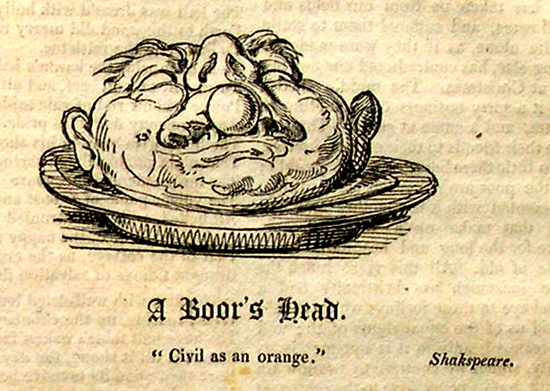

An engraving from a clever drawing by Rowlandson, in the possession of the editor of the Every-Day Book, may gracefully close this article.

A Boor's Head."Civil as an orange."

Shakspeare.

There are some just observations on the old mode of passing this season, in "the World," a periodical paper of literary pleasantries. "Our ancestors considered Christmas in the double light of a holy commemoration, and a cheerful festival, and accordingly distinguished it by devotion, by vacation from business, by merriment, and hospitality. They seemed eagerly bent to make themselves, and every one about them happy; with what punctual zeal did they wish one another a merry Christmas! and what an omission would it have been thought, to have concluded a letter without the compliments of the season! The great hall resounded with the tumultuous joys of servants and tenants, and the gambols they played served as amusement to the lord of the manor, and his family, who, by encouraging every conducive to mirth and entertainment, endeavoured to soften the rigour of the season, and mitigate the influence of winter."

The country squire of three hundred a year, an independent gentleman in the reign of queen Anne, is described as having "never played at cards but at Christmas, when the family pack was produced from the mantle-piece." "His chief drink the year round was generally ale, except at this season, the 5th of November, or some other gala days, when he would make a bowl of strong brandy punch, garnished with a toast and nutmeg. In the corner of his hall, by the fire-side, stood a large wooden two-armed chair, with a cushion, and within the chimney corner were a couple of seats. Here, at Christmas, he entertained his tenants, assembled round a glowing fire, made of the roots of trees, and other great logs, and told and heard the traditionary tales of the village, respecting ghosts and witches, till fear made them afraid to move. In the meantime the jorum of ale was in continual circulation."[3]

It is remarked, in the "Literary Pocket Book," that now, Christmas-day only, or at most a day or two, are kept by people in general; the rest are school holidays. "But, formerly, there was nothing but a run of merry days from Christmas-eve to Candlemas, and the first twelve in particular were full of triumph and hospitality. We have seen but too well the cause of this degeneracy. What has saddened our summer-time has saddened our winter. What has taken us from our fields and May-flowers, and suffered them to smile and die alone, as if they were made for nothing else, has contradicted our flowing cups at Christmas. The middle classes make it a sorry business of a pudding or so extra, and game at cards. The rich invite their friends to their country houses, but do little there but gossip and gamble; and the poor are either left out entirely, or presented with a few clothes and eatables that make up a wretched substitute for the long and hospitable intercourse of old. All this is so much the worse, inasmuch as christianity had a special eye to those feelings which should remind us of the equal rights of all; and the greatest beauty in it is not merely its charity, which we contrive to swallow up in faith, but its being alive to the sentiment of charity, which is still more opposed to these proud distances and formal dolings out.—The same spirit that vindicated the pouring of rich ointment on his feet, (because it was a homage paid to sentiment in his person,) knew how to bless the gift of a cup of water. Every face which you contribute to set sparkling at Christmas is a reflection of that goodness of nature which generosity helps to uncloud, as the windows reflect the lustre of the sunny heavens. Every holly bough and lump of berries with which you adorn your houses is a piece of natural piety as well as beauty, and will enable you to relish the green world of which you show yourselves not forgetful. Every wassail bowl which you set flowing without drunkenness, every harmless pleasure, every innocent mirth however mirthful, every forgetfulness even of serious things, when they are only swallowed up in the kindness of joy with which it is the end of wisdom to produce, is

'Wisest, virtuousest, discreetest, best;'

and Milton's Eve, who suggested those epithets to her husband, would have thought so too, if we are to judge by the poet's account of her hospitality."

ANCIENT CHRISTMAS.And well our christian sires of old

Loved, when the year its course had roll'd,

And brought blithe Christmas back again,

With all its hospitable train.

Domestic and religious rite

Gave honour to the holy night:

On Christmas-eve the bells were rung;

On Christmas-eve the mass was sung;

That only night, in all the year,

Saw the stoled priest the chalice rear.

The damsel donn'd her kirtle sheen;

The hall was dress'd with holly green;

Forth to the wood did merry men go,

To gather in the misletoe.

Then open wide the baron's hall,

To vassal, tenant, serf, and all;

Power laid his rod of rule aside,

And ceremony doff'd his pride.

The heir, with roses in his shoes,

That night might village partner choose:

The lord, underogating, share

The vulgar game of "post and pair."

All hailed, with uncontrouled delight,

And general voice, the happy night,

That to the cottage, as the crown,

Brought tidings of salvation down.The fire, with well-dried logs supply'd,

Went, roaring, up the chimney wide;

The huge hall table's oaken face,

Scrubb'd till it shone, the day to grace,

Bore then upon its massive board

No mark to part the squire and lord.

Then was brought in the lusty brawn,

By old blue-coated serving man;

Then the grim boar's-head frown'd on high,

Crested with bays and rosemary.

Well can the green-garb'd ranger tell,

How, when, and where the monster fell;

What dogs before his death he tore,

And all the baiting of the boar;

While round the merry wassel bowl,

Garnish'd with ribbons, blithe did trowl.

There the huge sirloin reek'd; hard by

Plum-porridge stood, and Christmas pie;

Nor fail'd old Scotland to produce,

At such high tide her savoury goose.

Then came the merry maskers in,

And carols roar'd with blithsome din;

If unmelodious was the song,

It was a hearty note and strong

Who lists may in their mumming see

Traces of ancient mystery;

White shirts supply the masquerade,

And smutted cheeks the visor made;

But, oh! what masquers, richly dight,

Can boast of bosoms half so light!

England was merry England when

Old Christmas brought his sports again.

'Twas Christmas broach'd the mightiest ale;

'Twas Christmas told the merriest tale;

A Christmas gambol oft would cheer

A poor man's heart through half the year.Sir Walter Scott.

WAITS.The musicians who play by night in the streets at Christmas are called waits. It has been presumed, that waits in very ancient times meant watchmen; they were minstrels at first attached to the king's court, who sounded the watch every night, and paraded the streets during winter to prevent depredations.

In London, the waits are remains of the musicians attached to the corporation of the city under that denomination. They cheer the hours of the long nights before Christmas with instrumental music. To denote that they were "the lord mayor's music," they anciently wore a cognizance, a badge on the arm, similar to the represented in the engraving below, from a picture by A. Bloemart.

The Piper.He blows his bagpipe soft or strong,

Or high or low, to hymn or song,

Or shrill lament, or solemn groan,

Or dance, or reel, or sad o-hone!

Or ballad gay, or well-a-day—

To all he gives due melody.

Preparatory to Christmas, the bellman of every parish in London rings his bell at dead midnight, that his "worthy masters and mistresses" may listen, and be assured by his vocal intonation that he is reciting "a copy of verses" in praise of their several virtues, especially their liberality; and, when the festival is over, he calls with his bell, and hopes he shall be "remembered."

At the good town of Bungay, in Suffolk, the "watch" of the year 1823 circulated the following, headed by a representation of a moiety of their dual body:—

A COPY OF CHRISTMAS VERSES,

PRESENTED TO THE

INHABITANTS OF BUNGAY

BY THEIR HUMBLE SERVANTS,

THE LATE WATCHMEN,

John Pye and John Tye.

YOUR pardon, Gentles, while we thus implore,

In strains not less awakening than of yore,

Those smiles we deem our best reward to catch,

And for the which we've long been on the Watch;

Well pleas'd if we that recompence obtain,

Which we have ta'en so many steps to gain.

Think of the perils in our calling past,

The chilling coldness of the midnight blast,

The beating rain, the swiftly-driving snow,

The various ills that we must undergo,

Who roam, the glow-worms of the human race,

The living Jack-a-lanthorns of the place.'Tis said by some, perchance, to mock our toil,

That we are prone to "waste the midnight oil!"

And that, a task thus idle to pursue,

Would be an idle waste of money too!

How hard, that we the dark designs should rue

Of those who'd fain make light of all we do!

But such the fate which oft doth merit greet,

And which now drives us fairly off our beat!

Thus it appears from this our dismal plight,

That some love darkness, rather than the light.Henceforth let riot and disorder reign,

With all the ills that follow in their train;

Let TOMS and JERRYS unmolested brawl,

(No Charlies have they now to floor withal,)

And "rogues and vagabonds" infest the Town,

For cheaper 'tis to save than crack a crown!To brighter scenes we now direct our view—

And first, fair Ladies, let us turn to you.

May each NEW YEAR new joys, new pleasures bring,

And Life for you be one delightful spring!

No summer's sun annoy with fev'rish rays,

No winter chill the evening of your days!To you, kind Sirs, we next our tribute pay:

May smiles and sunshine greet you on your way!

If married, calm and peacful be your lives;

If single, may you forthwith get you wives!Thus, whether Male or Female, Old or Young,

Or Wed or Single, be this burden sung:

Long may you live to hear, and we to call,

A Happy Christmas and New Year to all!

J. and R. Childs, Printers, Bungay.

Previous to Christmas 1825, a trio of foreign minstrels appeared in London, ushering the season with melody from instruments seldom performed on in the streets. These were Genoese with their guitars. Musicians of this order are common in Naples and all over Italy; at the carnival time they are fully employed, and at other periods are hired to assist in those serenades whereof English ladies hear nothing, unless they travel, save by the reports of those who publish accounts of their adventures. The three now spoken of took up their abode in London, at the King's-head public-house, in Leather-lane, from whence ever and anon, to wit, daily, they sallied forth to "discourse most excellent music." They are represented in the engraving below, from a sketch hastily taken by a gentleman who was of a dinner party, by whom they were called into the house of a street in the suburbs.

Italian Minstrels in London,AT CHRISTMAS, 1825.

Ranged in a row, with guitars slung

Before them thus, they played and sung:

Their instruments and choral voice

Bid each glad guest still more rejoice;

And each guest wish'd again to hear

Their wild guitars and voices clear.*

There was much of character in the men themselves. One was tall, and had that kind of face which distinguishes the Italian character; his complexion a clear pale cream colour, with dark eyes, black hair, and a manner peculiarly solemn: the second was likewise tall, and of more cheerful feature; but the third was a short thick-set man, with and Oxberry countenance of rich waggery, heightened by large whiskers: this was the humourist. With a bit of cherry-tree held between the finger and thumb, they rapidly twirled the wires in accompaniment of various airs, which they sung with unusual feeling and skill. They were acquainted with every foreign tune that was called for. That Italian minstrels of this class should venture here for the purpose of perambulating our streets, is evidence that the refinement in our popular manners is known in "the land of song," and they will bear testimony to it from the fact that their performances are chiefly in the public-houses of the metropolis, from whence thirty years ago such aspirants to entertain John Bull would have been expelled with expressions of abhorrence.

To the accounts of Christmas keeping in old times, old George Wither adds amusing particulars in rhime.

Christmas.So now is come our joyfulst feast;

Let every man be jolly;

Each room with ivy leaves is drest,

And every post with holly.

Though some churls at our mirth repine,

Round your foreheads garlands twine;

Drown sorrow in a cup of wine,

And let us all be merry.Now all our neighbours' chimnies smoke,

And Christmas blocks are burning;

Their ovens they with baked meat choke,

And all their spits are turning.

Without the door let sorrow lye;

And if for cold it hap to die,

We'll bury't in a Christmas pie,

And evermore be merry.Now every lad is wond'rous trim,

And no man minds his labour;

Our lasses have provided them

A bagpipe and a tabor;

Young men and maids, and girls and boys,

Give life to one another's joys;

And you anon shall by their noise

Perceive that they are merry.Rank misers now do sparing shun;

Their hall of music soundeth;

And dogs thence with whole shoulders run,

So all things there aboundeth.

The country folks, themselves advance,

With crowdy-muttons out of France;

And Jack shall pipe and Jyll shall dance,

And all the town be merry.Ned Squash hath fetch his bands from pawn,

And all his best apparel;

Brisk Nell hath bought a ruff of lawn

With dropping of the barrel.

And those that hardly all the year

Had bread to eat, or rags to wear,

Will have both clothes and dainty fare,

And all the day be merry.Now poor men to the justices

With capons make their errants;

And if they hap to fail of these,

They plague them with their warrants:

But now they feed them with good cheer,

And what they want, they take in beer,

For Christmas comes but once a year,

And then they shall be merry.Good farmers in the country nurse

The poor, that else were undone;

Some landlords spend their money worse,

On lust and pride at London.

There the roysters they do play,

Drab and dice their lands away,

Which may be ours another day,

And therefore let's be merry.The client now his suit forbears,

The prisoner's heart is eased;

The debtor drinks away his cares,

And for the time is pleased.

Though others' purses be more fat,

Why should we pine, or grieve at that?

Hang sorrow! care will kill a cat,

And therefore let's be merry.Hark! now the wags abroad do call,

Each other forth to rambling;

Anon you'll see them in the hall,

For nuts and apples scrambling.

Hark! how the roofs with laughter sound,

Anon they'll think the house goes round,

For they the cellar's depth have found,

And there they will be merry.The wenches with their wassel bowls

About the streets are singing;

The boys are come to catch the owls,

The wild mare in it bringing.

Our kitchen boy hath broke his box,

And to the dealing of the ox,

Our honest neighbours come by flocks,

And here they will be merry.Now kings and queens poor sheepcotes have,

And mute with every body;

The honest now may play the knave,

And wise men play the noddy.

Some youths will now a mumming go,

Some others play at Rowland-bo,

And twenty other game boys mo,

Because they will be merry.Then, wherefore, in these merry daies,

Should we, I pray, be duller?

No, let us sing some roundelayes,

To make our mirth the fuller.

And, while we thus inspired sing,

Let all the streets with echoes ring;

Woods and hills, and every thing,

Bear witness we are merry.

From Mr. Grant's "Popular Superstitions of the Highlands," we gather the following account:—

Highland Christmas.As soon as the brightening glow of the eastern sky warns the anxious housemaid of the approach of Christmas-day, she rises full of anxiety at the prospect of her morning labours. The meal, which was steeped in the sowans-bowie a fortnight ago, to make the Prechdachdan sour, or sour scones, is the first object of her attention. The gridiron is put on the fire, and the sour scones are soon followed by hard cakes, soft cakes, buttered cakes, brandered bannocks, and pannich perm. The baking being once over, the sowans pot succeeds the gridiron, full of new sowans, which are to be given to the family, agreeably to custom, this day in their beds. The sowans are boiled into the consistence of molasses, when the Lagan-le-vrich, or yeast-bread, to distinguish it from boiled sowans, is ready. It is then poured into as many bickers as there are individuals to partake of it, and presently served to the whole, old and young. It would suit well the pen of a Burns, or the pencil of a Hogarth, to paint the scene which follows. The ambrosial food is despatched in aspiring draughts by the family, who soon give evident proofs of the enlivening effects of the Lagan-le-vrich. As soon as each despatches his bicker, he jumps out of bed—the elder branches to examine the ominous signs of the day,*[4] and the younger to enter on its amusements. Flocking to the swing, a favourite amusement on this occasion the youngest of the family get the first "shoulder," and the next oldest to him in regular succession. In order to add the more to the spirit of the exercise, it is a common practice with the person in the swing, and the person appointed to swing him, to enter into a very warm and humorous altercation. As the swinged person approaches the swinger, he exclaims, Ei mi to chal, "I'll eat your kail." To this the swinger replies, with a violent shove, Cha ni u mu chal, "You shan't eat my kail." These threats and repulses are sometimes carried to such a height, as to break down or capsize the threatener, which generally puts an end to the quarrel.

As the day advances, those minor amusements are terminated at the report of the gun, or the rattle of the ball-clubs—the gun inviting the marksman to the "Kiavamuchd," or prize-shooting, and the latter to "Luchd-vouil," or the ball combatants—both the principal sports of the day. Tired at length of the active amusements of the field, they exchange them for the substantial entertainments of the table. Groaning under the sonsy haggis,"*[5] and many other savoury dainties, unseen for twelve months before, the relish communicated to the company, by the appearance of the festive board, is more easily conceived than described. The dinner once despatched, the flowing bowl succeeds, and the sparkling glass flies to and fro like a weaver's shuttle. As it continues its rounds, the spirits of the company become the more jovial and happy. Animated by its cheering influence, even old decrepitude no longer feels his habitual pains—the fire of youth is in his eye, as he details to the company the exploits which distinguished him in the days of "auld langsyne;" while the young, with hearts inflamed with "love and glory," long to mingle in the more lively scenes of mirth, to display their prowess and agility. Leaving the patriarchs to finish those professions of friendship for each other, in which they are so devoutly engaged, the younger part of the company will shape their course to the ball-room, or the card-table, as their individual inclinations suggest; and the remainder of the evening is spent with the greatest pleasure of which human nature is susceptible.

EVERGREENS AT CHRISTMAS.When Rosemary and Bays, the poet's crown,

Are bawl'd in frequent cries through all the town;

Then judge the festival of Christmass near,

Christmass, the joyous period of the year!

Now with bright Holly all the temples strow,

With Laurel greens, and sacred Misletow.Gay.

From ev'ry hedge is pluck'd by eager hands

The Holly branch with prickly leaves replete,

And fraught with berries of a crimson hue;

Which, torn asunder from its parent trunk,

Is straightway taken to the neighb'ring towns,

Where windows, mantels, candlesticks, and shelves,

Quarts, pints, decanters, pipkins, basons, jugs,

And other articles of household ware,

The verdant garb confess.R. J. Thorn.

The old and pleasant custom of decking our houses and churches at Christmas with evergreens is derived from ancient heathen practices. Councils of the church forbad christians to deck their houses with bay leaves and green boughs at the same time with the pagans; but this was after the church had permitted such doings in order to accomodate its ceremonies to those of the old mythology. Where druidism had existed, "the houses were decked with evergreens in December, that the sylvan spirits might repair to them, and remain unnipped with frost and cold winds, until a milder season had renewed the foliage of their darling abodes."* [6]Polydore Vergil says that, "Trimmyng of the Temples, with hangynges, floures, boughtes and garlondes, was taken of the heathen people, whiche decked their idols and houses with suche array." In old church calendars Christmas-eve is marked "Templa exornantur." Churches are decked.

The holly and the ivy still maintain some mastery at this season. At the two universities, the windows of the college chapels are decked with laurel. The old Christmas carol in MS. at the British Museum, quoted at p. 1598, continues in the following words:—

Ivy hath a lybe; she laghtit with the cold,

So mot they all hafe that wyth Ivy hold.

——————Nay, Ivy! Nay, hyt, &c.Holy hat berys as red as any Rose,

The foster the hunters, kepe hom from the doo.

——————Nay, Ivy! Nay, hyt, &c.Ivy hath berys as black as any slo;

Ther com the oule and ete hum as she goo.

——————Nay, Ivy! Nay, hyt, &c.Holy hath byrdys, aful fayre flok,

The Nyghtyngale, the Poppyngy, the gayntyl Lavyrok.

——————Nay, Ivy! Nay, hyt, &c.Good Ivy! what byrdys ast thou!

Non but the howlet that kreye 'How! How!'

——————Nay, Ivy! Nay, hyt shall not, &c.Mr. Brand infers from this, "that holly was used only to deck the inside of houses at Christmas: while ivy was used not only as a vintner's sign, but also among the evergreens at funerals." He also cites from the old tract, "Round about our Coal-fire, or Christmas Entertainments," that formerly "the rooms were embowered with holly, ivy, cyprus, bays, laurel, and misletoe, and a burning Christmas log in the chimney;" but he remarks, that "in this account the cyprus is quite a new article. Indeed I should as soon have expected to have seen the yew as the cypress used on this joyful occasion."

Mr. Brand is of opinion that "although Gay mentions the misletoe among those evergreens that were put up in churches, it never entered those sacred edifices but by mistake, or ignorance of the sextons; for it was the heathenish and profane plant, as having been of such distinction in the pagan rites of druidism, and it therefore had its place assigned it in kitchens, where it was hung up in great state with its white berries, and whatever female chanced to stand under it, the young man present either had a right or claimed one of saluting her, and of plucking off a berry at each kiss." He adds "I have made many diligent inquiries after the truth of this. I learnt at Bath that it never came into churches there. An old sexton at Teddington, in Middlesex, informed me that some misletoe was once put up in the church there, but was by the clergyman immediately ordered to be taken away." He quotes from the "Medallic History of Carausius," by Stukeley, who speaking of the winter solstice, our Christmas, says: "This was the most respectable festival of our druids called yule-tide; when misletoe, which they called all-heal, was carried in their hands and laid on their altars, as an emblem of the salutiferous advent of Messiah. The misletoe they cut off the trees with their upright hatchets of brass, called celts, put upon the ends of their staffs, which they carried in their hands. Innumerable are these instruments found all over the British Isles. The custom is still preserved in the north, and was lately at York. On the eve of Christmas-day they carry misletoe to the high altar of the cathedral and proclaim a public and universal liberty, pardon, and freedom to all sorts of inferior and even wicked people at the gates of the city towards the four quarters of heaven." This is only a century ago.

In an "Inquiry into the ancient Greek Game, supposed to have been invented by Palamedes," Mr. Christie speaks of the respect the northern nations entertained for the misletoe, and of the Celts and Goths being distinct in the instance of their equally venerating the misletoe about the time of the year when the sun approached the winter solstice. He adds, "we find by the allusion of Virgil, who compared the golden bough in infernis, to the misletoe, that the use of this plant was not unknown in the religious ceremonies of the ancients, particularly the Greeks, of whose poets he was the acknowledged imitator."

The cutting of the misletoe was a ceremony of great solemnity with our ancient ancestors. The people went in procession. The bards walked first singing canticles and hymns, a herald preceded three druids with implements for the purpose. Then followed the prince of the druids accompanied by all the people. He mounted the oak, and cutting the misletoe with a golden sickle, presented it to the other druids, who received it with great respect, and on the first day of the year distributed it among the people as a sacred and holy plant, crying, "The misletoe for the new year." Mr. Archdeacon Nares mentions, "the custom longest preserved was the hanging up of a bush of misletoe in the kitchen or servant's hall, with the charm attached to it, that the maid, who was not kissed under it at Christmas, would not be married in that year." This natural superstition still prevails.

Christmas Doughs, Pies, and Porridge.

The season offers its

—— customary treat,

A mixture strange of suet, currants, meat,

Where various tastes combine.Oxford Sausage.

Yule-dough, or dow, a kind of baby, or little image of paste, was formerly baked at Christmas, and presented by bakers to their customers, "in the same manner as the chandlers gave Christmas candles." They are called yule cakes in the county of Durham. Anciently, "at Rome, on the vigil of the nativity, sweetmeats were presented to the fathers in the Vatican, and all kinds of little images (no doubt of paste) were to be found at the confectioners' shops." Mr. Brand, who mentions these usages, thinks, "there is the greatest probability that we have had from hence both our yule-doughs, plum-porridge, and mince-pies, the latter of which are still in common use at this season. The yule-dough has perhaps been intended for an image of the child Jesus, with the Virgin Mary:" he adds, "it is now, if I mistake not, pretty generally laid aside, or at most retained only by children."

It is inquired by a writer in the "Gentleman's Magazine," 1783, "may not the minced pye, a compound of the choicest productions of the east, have in view the offerings made by the wise men, who came from afar to worship, bringing spices," &c. These were also called shrid-pies.

Christmasse Day.

No matter for plomb-porridge, or shrid-pie

Or a whole oxe offered in sacrifice

To Comus, not to Christ, &c.Sheppard's Epigrams, 1651.

Mr. Brand, from a tract in his library printed about the time of queen Elizabeth of James I. observes, that they were likewise called "minched pies."According to Selden's "Table Talk," the coffin shape of our Christmas pies, is in imitation of the cratch, or manger wherein the infant Jesus was laid. The ingredients and shape of the Christmas pie is mentioned in a satire of 1656, against the puritans:—

Christ-mass? give me my beads: the word implies

A plot, by its ingredients, beef and pyes.

The cloyster'd steaks with salt and pepper lye

Like Nunnes with patches in a monastrie.

Prophaneness in a conclave? Nay, much more,

Idolatrie in crust! ———

——— and bak'd by hanches, then

Serv'd up in coffins to unholy men;

Defil'd, with superstition, like the Gentiles

Of old, that worship'd onions, roots, and lentiles!R. Fletcher.

There is a further account in Misson's "Travels in England." He says, "Every family against Christmass makes a famous pye, which they call Christmas pye. It is a great nostrum; the composition of this pasty is a most learned mixture of neat's-tongues, chicken, eggs, sugar, raisins, lemon and orange peel, various kinds of spicery," &c. The most notably familiar poet of our seasonable customs interests himself for its safety:—

Come guard this night the Christmas-pie

That the thiefe, though ne'r so slie,

With his flesh hooks don't come nie

To catch it;From him, who all alone sits there,

Having his eyes still in his eare,

And a deale of nightly feare

To watch it.Herrick.

Mr. Brand observes, of his own knowledge, that "in the north of England, a goose is always the chief ingredient in the composition of a Christmas pye;" and to illustrate the usage, "further north," he quotes, that the Scottish poet Allan Ramsay, in his "Elegy on lucky Wood," tells us, that among other baits by which the good ale-wife drew customers to her house, she never failed to tempt them at Yule (Christmas,) with

"A bra' Goose Pye."

Further, from "Round about our Coal-fire," we likewise find that "An English gentleman at the opening of the great day, i.e. on Christmass day in the morning, had all his tenants and neighbours enter his hall by day-break. The strong beer was broached, and the black jacks went plentifully about with toast, sugar, nutmegg, and good Cheshire cheese. The hackin (the great sausage) must be boiled by day-break, or else two young men must take the maiden (i.e.) the cook, by the arms and run her round the market-place till she is ashamed of her laziness.

"In Christmass holidays, the tables were all spread from the first to the last; the sirloins of beef, the minced pies, the plumb porridge, the capons, turkeys, geese, and plum-puddings, were all brought upon the board: every one eat heartily, and was welcome, which gave rise to the proverb, 'merry in the hall when beards wag all.'"

Lastly, Mr. Brand makes this important note from personal regard. "Memorandum. I dined at the chaplain's table at St. James's on Christmas-day, 1801, and partook of the first thing served and eaten on that festival at that table, i.e. a tureen full of rich luscious plum-porridge. I do not know that the custom is any where else retained."

Thus has been brought together so much as, for the present, seems sufficient to describe the ancient and present estimation and mode of keeping Christmas.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Holly. Ilex bacciflora.

Dedicated to the Nativity of Jesus Christ.

It ought not, however, to be forgotten, that a scene of awful grandeur, hitherto misrepresented on the stage by the meanest of "his majesty's servants," opens the tragedy of Hamlet, wherein our everlasting bard refers to ancient and still existing tradition, that at the time of cock-crowing, the midnight spirits forsake these lower regions, and go to their proper places; and that the cocks crow throughout the live-long nights of Christmas—a circumstance observable at no other time of the year. Horatio, the friend of Hamlet, discourses at midnight with Francisco, a sentry on the platform before the Danish palace, and Bernardo and Marcellus, two officers of the guard, respecting the ghost of the deceased monarch of Denmark, which had appeared to the military on watch.Mar. Horatio says, 'tis but our fantasy,

And will not let belief take hold of him,

Touching this dreaded sight, twice seen of us;

Therefore I have entreated him, along

With us, to watch the minutes of this night;

That, if again this apparition come,

He may approve our eyes, and speak to it.Hor. Tush! tush! 'twill not appear.

Ber. Sit down awhile;

And let us once again assail your ears,

That are so fortified against our story,

What we two nights have seen.

———Last night of all,

When yon same star, that's westward from the pole,

Had made his course to illume that part of heaven

Where now it burns, Marcellus and myself,

The bell then beating one,———Mar. Peace, break thee off; look, where it comes again!

The ghost enters. Horatio is harrowed with fear and wonder. His companions urge him to address it; and somewhat recovered from astonishment, he urges "the majesty of bury'd Denmark" to speak. It is offended, and stalks away.

Mar. Thus, twice before, and just at this dead hour,

With martial stalk he hath gone by our watch.Horatio discourses with his companions on the disturbed state of the kingdom, and the appearance they have just witnessed; whereof he ways, "a mote it is, to trouble the mind's eye." He is interrupted by its re-entry, and invokes it, but the apparition remains speechless; the "cock crows," and the ghost is about to disappear, when Horatio says,

—— Stay, and speak, — Stop it, Marcellus.

Mar. Shall I strike at it with my partizan?

Hor. Do, if it will not stand.

Ber. 'Tis here!

Hor. 'Tis here!

Mar. 'Tis gone! [Exit Ghost.

We do it wrong, being so majestical,

To offer it the show of violence;

For it is, as the air, invulnerable,

And our vain blows malicious mockery.Ber. It was about to speak, when the cock crew.

Hor. And then it started, like a guilty thing

Upon a fearful summons. I have heard,

The cock, that is the trumpet of the morn,

Doth with his lofty and shrill-sounding throat

Awake the god of day; and, at this warning,

Whether in sea or fire, in earth or air,

The extravagant and erring spirit hies

To his confine: and of the truth herein

This present object makes probation.Marcellus answers, "It faded on the crowing of the cock," and concludes on the vigilance of this bird, previous to the solemn festival, in a strain of superlative beauty:—

Some say, that ever 'gainst that season comes

Wherein our Saviour's birth is celebrated,

This bird of dawning singeth all night long:

And then, they say, no spirit stirs abroad;

The nights are wholesome; then no planet strikes;

No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm,

So hallow'd and so gracious is the time.