To the Reader.

I am encouraged, by the approbation of my labours, to persevere in the completion of my plan, and to continue this little work next year as usual.

Not a sentence that has appeared in the preceding sheets will be repeated, and the Engravings will be entirely new.

W. HONE.

December 1825.

December 24.Sts. Thrasilla and Emiliana. St. Gregory, of Spoleto, A. D. 304.

Christmas Eve.This is the vigil of that solemn festival which commemorates the day that gave

"To man a saviour—freedom to the slave."

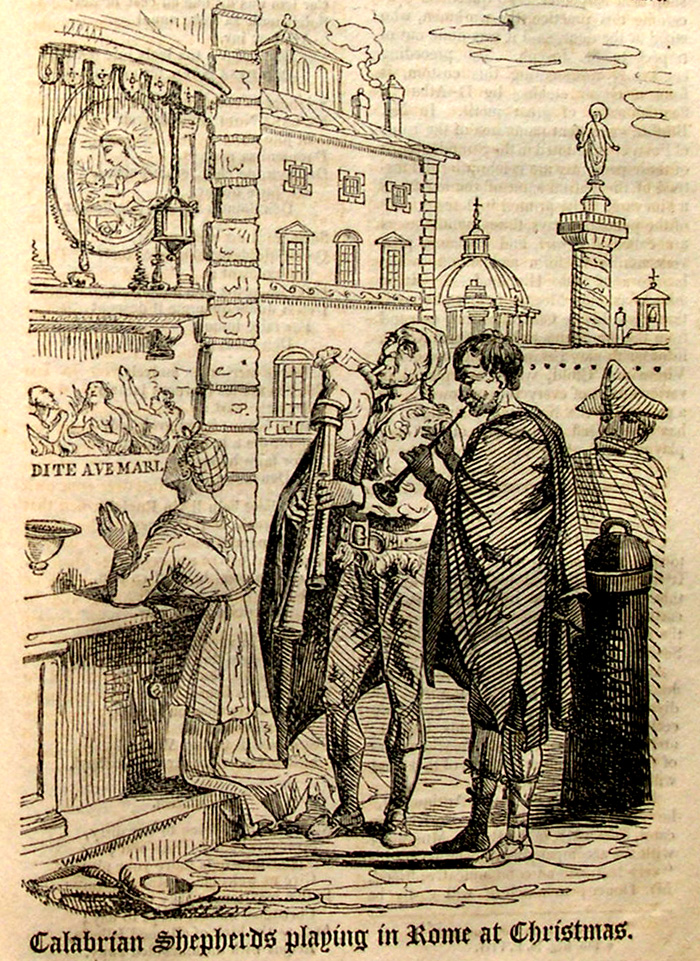

Calabrian Shepherds playing in Rome at Christmas.In the last days of Advent the Calabrian minstrels enter Rome, and are to be seen in every street saluting the shrines of the virgin mother with their wild music, under the traditional notion of soothing her until the birth-time of her infant at the approaching Christmas. This circumstance is related by lady Morgan, who observed them frequently stopping at the shop of a carpenter. To questions concerning this practice, the workmen, who stood at the door, said it was done out of respect to St. Joseph. The preceding engraving, representing this custom, is from a clever etching by D. Allan, a Scottish artist of great merit. In Mr. Burford's excellent panorama of the ruins of Pompeii, exhibited in the Strand, groups of these peasantry are celebrating the festival of the patron saint of the master of a vineyard. The printed "Description" of the panorama says, these mountaineers are called Pifferari, and "play a pipe very similar in form and sound to the bagpipes of the Highlanders." It is added, as lady Morgan before observed, that "just before Christmas they descend from the mountains to Naples and Rome, in order to play before the pictures of the Virgin and Child, which are placed in various parts of every Italian town." In a picture of the Nativity by Raphael, he has introduced a shepherd at the door playing on the bagpipes.

Christmas Carols.

Carol is said to be derived from cantare, to sing, and rola, an interjection of joy.*[1] It is rightly observed by Jeremy Taylor, that "Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, and good-will towards men," the song of the angels on the birth of the Saviour, is the first Christmas carol.

Anciently, bishops carolled at Christmas among their clergy; but it would be diverging into a wide field to exemplify ecclesiastical practices on this festival; and to keep close to the domestic usages of the season, church customs of that kind will not now be noticed.

In Mr. Brand's "Popular Antiquities," he gives the subjoined Anglo-Norman carol, from a MS. in the British Museum,† [2] with the accompanying translation by his "very learned and communicative friend, Mr. Douce; in which it will easily be observed that the translator has necessarily been obliged to amplify, but endeavours every where to preserve the sense of the original."

Anglo-Norman Carol.Seignors ore entendez a nus,

De loinz sumes venuz a wous,

Pur quere NOEL;

Car lem nus dit que en cest hostel

Soleit tenir sa feste anuel

Ahi cest iur.

Deu doint a tuz icels joie d'amurs

Qi a DANZ NOEL ferunt honors.Seignors io vus di por veir

KE DANZ NOEL ne uelt aveir

Si joie non;

E repleni sa maison,

De payn, de char, & de peison,

Por faire honor.

Deu doint a tuz ces joie damur.Seignors il est crie en lost,

Qe cil qui despent bien & tost,

E largement;

E fet les granz honors sovent

Deu li duble quanque il despent

Por faire honor.

Deu doint a.Seignors escriez les malveis,

Car vus nel les troverez jameis

De bone part:

Botun, batun, ferun groinard,

Car tot dis a le quer cuuard

Por faire honor.

Deu doint.NOEL beyt bein li vin Engleis

E li Gascoin & li Franceys

E l'Angeuin:

NOEL fait beivre son veisin,

Si quil se dort, le chief en clin,

Sovent le ior.

Deu doint a tuz cels.Seignors io vus di par NOEL,

E par li sires de cest hostel,

Car benez ben:

E io primes beurai le men,

E pois apres chescon le soen,

Par mon conseil,

Si io vus di trestoz Wesseyl

Dehaiz eit qui ne dirra Drincheyl.

Translation.

Now, lordings, listen to our ditty,

Strangers coming from afar;

Let poor minstrels move your pity,

Give us welcome, soothe our care:

In this mansion, as they tell us,

Christmas wassell keeps to day;

And, as the king of all good fellows,

Reigns with uncontrouled sway.Lordings, in these realms of pleasure,

Father Christmas yearly dwells;

Deals out joy with liberal measure,

Gloomy sorrow soon dispels:

Numerous guests, and viands dainty,

Fill the hall and grace the board;

Mirth and beauty, peace and plenty,

Solid pleasures here afford.Lordings, 'tis said the liberal mind,

That on the needy much bestows,

From Heav'n a sure reward shall find;

From Heav'n, whence ev'ry blessing flows.

Who largely gives with willing hand,

Or quickly gives with willing heart,

His fame shall spread throughout the land,

His memory thence shall ne'er depart.Lordings, grant not your protection

To a base, unworthy crew,

But cherish, with a kind affection,

Men that are loyal, good, and true.

Chace from your hospitable dwelling

Swinish souls, that ever crave;

Virtue they can ne'er excel in,

Gluttons never can be brave.Lordings, Christmas loves good drinking,

Wines of Gascoigne, France, Anjou,*[3]

English ale, that drives out thinking,

Prince of liquors old or new.

Every neighbour shares the bowl,

Drinks of the spicy liquor deep,

Drinks his fill without controul,

Till he drowns his care in sleep.And now—by Christmas, jolly soul!

By this mansion's generous sire!

By the wine, and by the bowl,

And all the joys they both inspire!

Here I'll drink a health to all.

The glorious task shall first be mine:

And ever may foul luck befal

Him that to pledge me shall decline!THE CHORUS.

Hail, father Christmas! hail to thee!

Honour'd ever shalt thou be!

All the sweets that love bestows,

Endless pleasures, wait on those

Who, like vassals brave and true,

Give to Christmas homage due.

From what has been observed of Christmas carols in another work, by the editor, a few notices will be subjoined with this remark, that the custom of singing carols at Christmas is very ancient; and though most of those that exist at the present day are deficient of interest to a refined ear, yet they are calculated to awaken tender feelings. For instance, one of them represents the virgin contemplating the birth of the infant, and saying,

"He neither shall be clothed

in purple nor in pall,

But all in fair linen,

as were babies all:

He neither shall be rock'd

in silver nor in gold,

But in a wooden cradle,

that rocks on the mould."Not to multiply instances at present, let it suffice that in a MS. at the British Museum*[4] there is "A song on the holly and the ivy," beginning,

"Nay, my nay, hyt shal not be I wys,

Let holy hafe the maystry, as the maner ys:"Holy stond in the hall, fayre to behold,

Ivy stond without the dore, she ys ful sore acold.

"Nay my nay," &c."Holy, & hys mery men, they dawnsyn and they syng,

Ivy and hur maydyns, they wepyn & they wryng.

"Nay my nay," &c.The popularity of carol-singing occasioned the publication of a duodecimo volume in 1642, intitled, "Psalmes or Songs of Sion, turned into the language, and set to the tunes of a strange land. By W(illiam) S(layter), intended for Christmas carols, and fitted to divers of the most noted and common but solemne tunes, every where in this land familiarly used and knowne." Upon the copy of this book in the British Museum, a former possessor has written the names of some of the tunes to which the author designed them to be sung: for instance, Psalm 6, to the tune of Jane Shore; Psalm 19, to Bar. Forster's Dreame; Psalm 43, to Crimson Velvet; Psalm 47, to Garden Greene; Psalm 84, to The fairest Nymph of the Valleys; &c.

In a carol, still sung, called "Dives and Lazarus," there is this amusing account:

"As it fell it out, upon a day,

Rich Dives sicken'd and died,

There came two serpents out of hell,

His soul therein to guide."Rise up, rise up, brother Dives,

And come along with me,

For you've a place provided in hell,

To set upon a serpent's knee."However whimsical this may appear to the reader, he can scarcely conceive its ludicrous effect, when the "serpent's knee" is solemnly drawn out to its utmost length by a Warwickshire chanter, and as solemnly listened to by the well-disposed crowd, who seem, without difficulty, to believe that Dives sits on a serpent's knee. The idea of sitting on this knee was, perhaps, conveyed to the poet's mind by old wood-cut representations of Lazarus seated in Abraham's lap. More anciently, Abraham was frequently drawn holding him up by the sides, to be seen by Dives in hell. In an old book now before me, they are so represented, with the addition of a devil blowing the fire under Dives with a pair of bellows.

Carols begin to be spoken of as not belonging to this century, and few, perhaps, are aware of the number of these compositions now printed. The editor of the Every-Day Book has upwards of ninety, all at this time, published annually.

This collection he has had little opportunity of increasing, except when in the country he has heard an old woman singing an old carol, and brought back the carol in his pocket with less chance of its escape, than the tune in his head.

Mr. Southey, describing the fight "upon the plain of Patay," tells of one who fell, as having

"In his lord's castle dwelt, for many a year,

A well-beloved servant: he could sing

Carols for Shrove-tide, or for Candlemas,

Songs for the wassel, and when the boar's head

Crown'd with gay garlands, and with rosemary,

Smoak'd on the Christmas board."Joan of Arc, b. x. 1. 466.

These ditties, which now exclusively enliven the industrious servant-maid, and the humble labourer, gladdened the festivity of royalty in ancient times. Henry VII., in the third year of his reign, kept his Christmas at Greenwich: on the twelfth night, after high mass, the king went to the hall, and kept his estate at the table; in the middle sat the dean, and those of the king's chapel, who, immediately after the king's first course, "sang a carall."*[5] Granger innocently observes, that "they that fill the highest and the lowest classes of human life, seem in many respects to be more nearly allied than even themselves imagine. A skilful anatomist would find little or no difference in dissecting the body of a king, and that of the meanest of his subjects; and a judicious philosopher would discover a surprising conformity in discussing the nature and qualities of their minds."*[6]

The earliest collection of Christmas carols supposed to have been published, is only known from the last leaf of a volume printed by Wynkn de Worde, in the year 1521. This precious scrap was picked up by Tom Hearne; Dr. Rawlinson purchased it at his decease in a volume of tracts, and bequeathed it to the Bodleian library. There are two carols upon it: one, "a caroll of huntynge," is reprinted in the last edition of Juliana Berners' "Boke of St. Alban's;" the other, "a caroll, bringing in the bore's head," is in Mr Dibdin's "Ames," with a copy of it as it is now sung in Queen's-college, Oxford, every Christmas-day. Dr. Bliss, of Oxford, also printed on a sheet for private distribution, a few copies of this and Ant. a Wood's version of it [sic], with notices concerning the custom, from the hand-writings of Wood and Dr. Rawlinson, in the Bodleian library. Ritson, in his ill-tempered "Observations on Warton's History of English Poetry," (1782, 4to. p. 37,) has a Christmas carol upon bringing up the boar's head, from an ancient MS. in his possession, wholly different from Dr. Bliss's. The "Bibliographical Miscellanies," (Oxford, 1813, 4to.) contains seven carols from a collection in one volume in the possession of Dr. Cotton, of Christchurch-college, Oxford, "imprynted at London, in the Powltry, by Richard Kele, dwellyng at the longe shop vnder saynt Myldrede's Chyrche," probably "between 1546 and 1552." I had an opportunity of perusing this exceedingly curious volume, which is supposed to be unique, and has since passed into the hands of Mr. Freeling. There are carols among the Godly and Spiritual Songs and Balates, in "Scottish Poems of the sixteenth century," (1801, 8vo.); and one by Dunbar, from the Bannatyne MS. in "Ancient Scottish Poems." Others are in Mr. Ellis's edition of Brand's "Popular Antiquities," with several useful notices. Warton's "History of English Poetry" contains much concerning old carols. Mr. Douce, in his "Illustrations of Shakspeare," gives a specimen of the carol sung by the shepherds, on the birth of Christ, in one of the Coventry plays. There is a sheet of carols headed thus: "CHRISTUS NATUS EST: Christ is born;" with a wood-cut, 10 inches high, by 8½ inches wide, representing the stable at Bethlehem; Christ is in the crib, watched by the virgin and Joseph; shepherds kneeling; angels attending; a man playing on the bagpipes; a woman with a basket of fruit on her head; a sheep bleating, and an ox lowing on the ground; a raven croaking, and a crow cawing on the hay-rack; a cock crowing above them; and angels singing in the sky. The animals have labels from their mouths, bearing Latin inscriptions. Down the side of the wood-cut is the following account and explanation: "A religious man, inventing the conceits of both birds and beasts, drawn in the picture of our Saviour's birth, doth thus express them: the cock croweth, Christus natus est, Christ is born. The raven asked, Quando? When? The crow replied, Hac nocte, This night. The ox cryeth out, Ubi? Ubi? Where? where? The sheep bleated out, Bethlehem, Bethlehem. A voice from heaven sounded, Gloria in Excelsis, Glory be on high.—London: printed and sold by J. Bradford, in Little Britain, the corner house over against the Pump, 1701. Price One Penny." This carol is in the possession of Mr. Upcott.

The custom of singing carols at Christmas prevails in Ireland to the present time. In Scotland, where no church feasts have been kept since the days of John Knox, the custom is unknown. In Wales it is still preserved to a greater extent, perhaps, than in England; at a former period, the Welsh had carols adapted to most of the ecclesiastical festivals, and the four seasons of the year, but in our times they are limited to that of Christmas. After the turn of midnight at Christmas-eve, service is performed in the churches, followed by the singing of carols to the harp. Whilst the Christmas holidays continue, they are sung in like manner in the houses, and there are carols especially adapted to be sung at the doors of the houses by visiters before they enter. Lffyr Carolan, or the book of carols, contains sixty-six for Christmas, and five summer carols; Blodeugerdd Cymrii, or the "Anthology of Wales," contains forty-eight Christmas carols, nine summer carols, three May carols, one winter carol, one nightingale carol, and a carol to Cupid. The following verse of a carol for Christmas is literally translated from the first mentioned volume. The poem was written by Hugh Morris, a celebrated songwriter during the commonwealth, and until the early part of the reign of William III:—

"To a saint let us not pray, to a pope let us not kneel;

On Jesu let us depend, and let us discreetly watch

To preserve our souls from Satan with his snares;

Let us not in morning invoke any one else."With the succeeding translation of a Welsh wassail song, the observer of manners will, perhaps, be pleased. In Welsh, the lines of each couplet, repeated inversely, still keep the same sense.

A Carol for the Eve of St. Mary's Day.This is the season when, agreeably to custom,

That it was an honour to send wassail

By the old people who were happy

In their time, and loved pleasure;

And we are now purposing

To be like them, every one merry:

Merry and foolish, youths are wont to be,

Being reproached for squandering abroad.

I know that every mirth will end

Too soon of itself;

Before it is ended, here comes

The wassail of Mary, for the sake of the time:

N ———*[7] place the maid immediately

In the chair before us;

And let every body in the house be content that we

May drink wassail to virginity,

To remember the time, in faithfulness,

When fair Mary was at the sacrifice,

After the birth to her of a son,

Who delivered every one, through his good will

From their sins, without doubt.

Should there be an inquiry who made the carol,

He is a man whose trust is fully on God,

That he shall go to heaven to the effulgent Mary,

Towards filling orders where she also is.THOMAS EVANS.

In the rage for "collecting" almost every thing, it is surprising that "collectors" have almost overlooked carols, as a class of popular poetry. To me they have been objects of interest from circumstances which occasionally determine the direction of pursuit. The wood-cuts round the annual sheets, and the melody of "God rest you merry gentlemen," delighted my childhood; and I still listen with pleasure to the shivering carolist's evening chant towards the clean kitchen window decked with holly, the flaring fire showing the whitened hearth, and reflecting gleams of light from the surfaces of the dresser utensils.Davies Gilbert, Esq. F.R.S. F.A.S. &c. has published "Ancient Christmas carols, with the tunes to which they were formerly sung in the west of England." Mr. Gilbert says, that "on Christmas-day these carols took the place of psalms in all the churches, especially at afternoon service, the whole congregation joining: and at the end it was usual for the parish clerk, to declare in a loud voice, his wishes for a merry Christmas and a happy new year."

In "Poor Robin's Almanac," for 1695, there is a Christmas carol, which is there called, "A Christmas Song," beginning thus:—

Now thrice welcome, Christmas,

Which brings us good cheer,

Minced-pies and plumb-porridge,

Good ale and strong beer;

With pig, goose, and capon,

The best that may be,

So well doth the weather

And our stomachs agree.Observe how the chimneys

Do smoak all about,

The cooks are providing

For dinner, no doubt;

But those on whose tables

No victuals appear,

O, may they keep Lent

All the rest of the year!With holly and ivy

So green and so gay;

We deck up our houses

As fresh as the day.

With bays and rosemary

And laurel compleat,

And every one now

Is a king in conceit.

So much only concerning carols for the present. But more shall be said hereon in the year 1826, if the editor of the Every-Day Book live, and retain his faculties to that time. He now, however, earnestly requests of every one of its readers in every part of England, to collect every carol that may be singing at Christmas time in the year 1825, and convey these carols to him at their earliest convenience, with accounts of manners and customs peculiar to their neighbourhood, which are not already noticed in this work. He urges and solicits this most earnestly and anxiously, and prays his readers not to forget that he is a serious and needy suitor. They see the nature of the work, and he hopes that any thing and every thing that they think pleasant or remarkable, they will find some means of communicating to him without delay. The most agreeable presents he can receive at any season, will be contributions and hints that may enable him to blend useful information with easy and cheerful amusement.

CUSTOMS ON

Christmas Eve.

Mr. Coleridge writing his "Friend," from Ratzeburg, in the north of Germany, mentions a practice on Christmas-eve very similar to some on December 6th, St. Nicholas'-day. Mr. Coleridge says, "There is a Christmas custom here which pleased and interested me. The children make little presents to their parents, and to each other, and the parents to the children. For three or four months before Christmas the girls are all busy, and the boys save up their pocket-money to buy these presents. What the present is to be is cautiously kept secret; and the girls have a world of contrivances to conceal it—such as working when they are out on visits, and the others are not with them—getting up in the morning before day-light, &c. Then, on the evening before Christmas-day, one of the parlours is lighted up by the children, into which the parents must not go; a great yew bough is fastened on the table at a little distance from the wall, a multitude of little tapers are fixed in the bough, but not so as to burn it till they are nearly consumed, and coloured paper, &c. hangs and flutters from the twigs. Under this bough the children lay out in great order the presents they mean for their parents, still concealing in their pockets what they intend for each other. Then the parents are introduced, and each presents his little gift; they then bring out the remainder one by one, from their pockets, and present them with kisses and embraces. Where I witnessed this scene, there were eight or nine children, and the eldest daughter and the mother wept aloud for joy and tenderness; and the tears ran down the face of the father, and he clasped all his children so tight to his breast, it seemed as if he did it to stifle the sob that was rising within it. I was very much affected. The shadow of the bough and its appendages on the wall, and arching over on the ceiling, made a pretty picture; and then the raptures of the very little ones, when at last the twigs and their needles began to take fire and snap—O it was a delight to them!—On the next day, (Christmas-day) in the great parlour, the parents lay out on the table the presents for the children; a scene of more sober joy succeeds; as on this day, after an old custom, the mother says privately to each of her daughters, and the father to his sons, that which he has observed most praiseworthy and that which was most faulty in their conduct. Formerly, and still in all the smaller towns and villages throughout North Germany, these presents were sent by all the parents to some one fellow, who, in high buskins, a white robe, a mask, and an enormous flax wig, personates Knecht Rupert, i. e. the servant Rupert. On Christmas-night he goes round to every house, and says, that Jesus Christ, his master, sent him thither. The parents and elder children receive him with great pomp and reverence, while the little ones are most terribly frightened. He then inquires for the children, and, according to the character which he hears from the parents, he gives them the intended present, as if they came out of heaven from Jesus Christ. Or, if they should have been bad children, he gives the parents a rod, and, in the name of his master, recommends them to use it frequently. About seven or eight years old the children are let into the secret, and it is curious how faithfully they keep it."

A correspondent to the "Gentleman's Magazine," says, that when he was a school-boy, it was a practice on Christmas-eve to roast apples on a string till they dropt into a large bowl of spiced ale, which is the whole composition of lamb's wool. Brand thinks, that this popular beverage obtained its name from the softness of the composition, and he quotes from Shakspeare's "Midsummer-Night's Dream,"

——— "Sometimes lurk I in a gossip's bowl,

In very likeness of a roasted crab;

And, when she drinks, against her lips I bob,

And on her wither'd dew-lap pour the ale."It was formerly a custom in England on Christmas-eve to wassail, or wish health to the apple-tree. Herrick enjoins to—

"Wassaile the trees, that they may beare

You many a plum, and many a peare;

For more or lesse fruits they will bring,

And you do give them wassailing."In 1790, it was related to Mr. Brand, by sir Thomas Acland, and Werington, that in his neighbourhood on Christmas-eve it was then customary for the country people to sing a wassail or drinking-song, and throw the toast from the wassail-bowl to the apple-trees in order to have a fruitful year.

"Pray remember," says T. N. of Cambridge, to the editor of the Every-Day Book, "that it is a Christmas custom from time immemorial to send and receive presents and congratulations from one friend to another; and, could the number of baskets that enter London at this season be ascertained, it would be astonishing; exclusive of those for sale, the number and weight of turkeys only, would surpass belief. From a historical account of Norwich it appears, that between Saturday morning and the night of Sunday, December 22, 1793, one thousand seven hundred turkeys, weighing 9 tons, 2 cwt. 2 lbs. value 680l. were sent from Norwich to London; and two days after half as many more."

"Now," says Stevenson, in his Twelve Months, 1661, "capons and hens, besides turkeys, geese, ducks, with beef and mutton, must all die; for in twelve days a multitude of people will not be fed with a little. Now plums and spice, sugar and honey, square it among pies and broth. Now a journeyman cares not a rush for his master, though he begs his plum-porridge all the twelve days. Now or never must the music be in tune, for the youth must dance and sing to get them a heat, while the aged sit by the fire. The country-maid leaves half her market, and must be sent again if she forgets a pack of cards on Christmas-eve. Great is the contention of holly and ivy, whether master or dame wears the breeches; and if the cook do not lack wit, he will sweetly lick his fingers."

Mr. Leigh Hunt's Indicator presents this Christmas picture to our contemplation—full of life and beauty:—

HOLIDAY CHILDREN.One of the most pleasing sights at this festive season is the group of boys and girls returned from school. Go where you will, a cluster of their joyous chubby faces present themselves to our notice. In the streets, at the panorama, or play-house, our elbows are constantly assailed by some eager urchin whose eyes just peep beneath to get a nearer view.

I am more delighted in watching the vivacious workings of their ingenuous countenances at these Christmas shows, than at the sights themselves.

From the first joyous huzzas, and loud blown horns which announce their arrival, to the faint attempts at similar mirth on their return, I am interested in these youngsters.

Observe the line of chaises with their swarm-like loads hurrying to tender and exulting parents, the sickly to be cherished, the strong to be amused; in a few mornings you shall see them, new clothes, warm gloves, gathering around their mother at every toy-shop, claiming the promised bat, hoop, top, or marbles; mark her kind smile at their ecstasies; her prudent shake of the head at their multitudinous demands; her gradual yielding as they coaxingly drag her in; her patience with their whims and clamour while they turn and toss over the play-things, as now a sword, and now a hoop is their choice, and like their elders the possession of one bauble does but make them sigh for another.

View the fond father, his pet little girl by the hand, his boys walking before on whom his proud eye rests, while ambitious views float o'er his mind for them, and make him but half attentive to their repeated inquiries; while at the Museum or Picture-gallery, his explanations are interrupted by the rapture of discovering that his children are already well acquainted with the different subjects exhibited.

Stretching half over the boxes at the theatre, adorned by maternal love, see their enraptured faces now turned to the galleries wondering at their height and at the number of regular placed heads contained in them, now directed towards the green cloud which is so lingeringly kept between them and their promised bliss. The half-peeled orange laid aside when the play begins; their anxiety for that which they understand; their honest laughter which runs through the house like a merry peal of sweet bells; the fear of the little girl lest they should discover the person hid behind the screen; the exultation of the boy when the hero conquers.

But, oh, the rapture when the pantomime commences! Ready to leap out of the box, they joy in the mischief of the clown, laugh at the thwacks he gets for his meddling, and feel no small portion of contempt for his ignorance in not knowing that hot water will scald and gunpowder explode; while with head aside to give fresh energy to the strokes, they ring their little palms against each other in testimony of exuberant delight.

Who can behold them without reflecting on the many passions that now lie dormant in their bosoms, to be in a few years agitating themselves and the world. Here the coquet begins to appear in the attention paid to a lace frock or kid gloves for the first time displayed, or the domestic tyrant in the selfish boy, who snatches the largest cake, or thrusts his younger brother and sister from the best place.

At no season of the year are their holidays so replete with pleasures; the expected Christmas-box from grand-papa and grand-mamma; plum-pudding and snap-dragon, with blindman's-buff and forfeits; perhaps to witness a juvenile play rehearsed and ranted; galantée-show and drawing for twelfth-cake; besides Chrismas gambols in abundance, new and old.

Even the poor charity-boy at this season feels a transient glow of cheerfulness, as with pale blue face, frost-nipped hands, and ungreatcoated, from door to door, he timidly displays the unblotted scutcheon of his graphic talents, and feels that the pence bestowed are his own, and that for once in his life he may taste the often desired tart, or spin a top which no one can snatch from him in capricious tyranny.

Ancient Representation of the Nativity.

THE OX AND THE ASS.

According to Mr. Brand, "a superstitious notion prevails in the western parts of Devonshire, that at twelve o'clock at night on Christmas-eve, the oxen in their stalls are always found on their knees, as in an attitude of devotion; and that (which is still more singular) since the alteration of the style, they continue to do this only on the eve of old Christmas-day. An honest countryman, living on the edge of St. Stephen's Down, near Launceston, Cornwall, informed me, October 28, 1790, that he once, with some others, made a trial of the truth of the above, and watching several oxen in their stalls at the above time, at twelve o'clock at night, they observed the two oldest oxen only fall upon their knees, and, as he expressed it in the idiom of the country, make 'a cruel moan like christian creatures.' I could not but with great difficulty keep my countenance: he saw, and seemed angry that I gave so little credit to his tale, and walking off in a pettish humour, seemed to 'marvel at my unbelief.' There is an old print of the Nativity, in which the oxen in the stable, near the virgin and the child, are represented upon their knees, as in a suppliant posture. This graphic representation has probably given rise to the above superstitious notion on this head." Mr. Brand refers to "an old print," as if he had only observed one with this representation; whereas, they abound, and to the present day the ox and the ass are in the wood-cuts of the nativity on our common Christmas carols. Sannazarius, a Latin poet of the fifteenth century, in his poem De Partu Virginis, which he was several years in revising, and which chiefly contributed to the celebrity of his name among the Italians, represents that the virgin wrapped up the new-born infant, and put him into her bosom; that the cattle cherished him with their breath, an ox fell on his knees, and an ass did the same. He declares them both happy, promises they shall be honoured at all the altars in Rome, and apostrophizes the virgin on occasion of the respect the ox and ass have shown her. To a quarto edition of this Latin poem, with an Italian translation by Gori, printed at Florence in 1740, there is a print inscribed "Sacrum monumentum in antiquo vitro Romæ in Musea Victorio," from whence the preceding engraving is presented, as a curious illustration of the obviously ancient mode of delineating the subject.

In the edition just mentioned of Sannazarius's exceedingly curious poem, which is described in the editor's often cited volume on "Ancient Mysteries," there are other engravings of the nativity with the ox and the ass, from sculptures on ancient sarcophagi at Rome. This introduction of the ox and the ass warming the infant in the crib with their breath, is a fanciful construction by catholic writers on Isaiah i. 3; "The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master's crib."

Sannazarius was a distinguished statesman in the kingdom of Naples. His superb tomb in the church of St. Mark is decorated with two figures originally executed for and meant to represent Apollo and Minerva; but as it appeared indecorous to admit heathen divinities into a christian church, and the figures were thought too excellent to be removed, the person who shows the church is instructed to call them David and Judith: "You mistake," said a sly rogue who was on of a party surveying the curiosities, "the figures are St. George, and the queen of Egypt's daughter." The demonstrator made a low bow, and thanked him.*[8]

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Frankincense. Pinus Tæda.

Dedicated to Sts. Thrasilla and Emiliana.