November 25.

St. Catharine. 3d. Cent. St. Erasmus, or Elme.

St. Catharine.This saint is in the church of England calendar, and the almanacs. It is doubtful whether she ever existed; yet in mass-books and breviaries, we find her prayed to and honoured by hymns, with stories of her miracles so wonderfully apocryphal that even cardinal Baronius blushes for the threadbare legends. In Alban Butler's memoirs of this saint, it may be discovered by a scrutinizing eye, that while her popularity seems to force him to relate particulars concerning her, he leaves himself room to disavow them; but this is hardly fair, for the great body of readers of his "Lives of the Saints," are too confiding to criticise hidden meanings. "From this martyr's uncommon erudition," he says, "and the extraordinary spirit of piety by which she sanctified her learning, and the use she made of it, she is chosen, in the schools, the patroness and model of christian philosophers." According to his authorities she was beheaded under the emperor Maxentius, or Maximinus II. He adds, "She is said first to have been put upon an engine made of four wheels joined together, and stuck with sharp pointed spikes, that when the wheels were moved her body might be torn to pieces. The acts add, that at the first stirring of the terrible engine, the cords with which the martyr

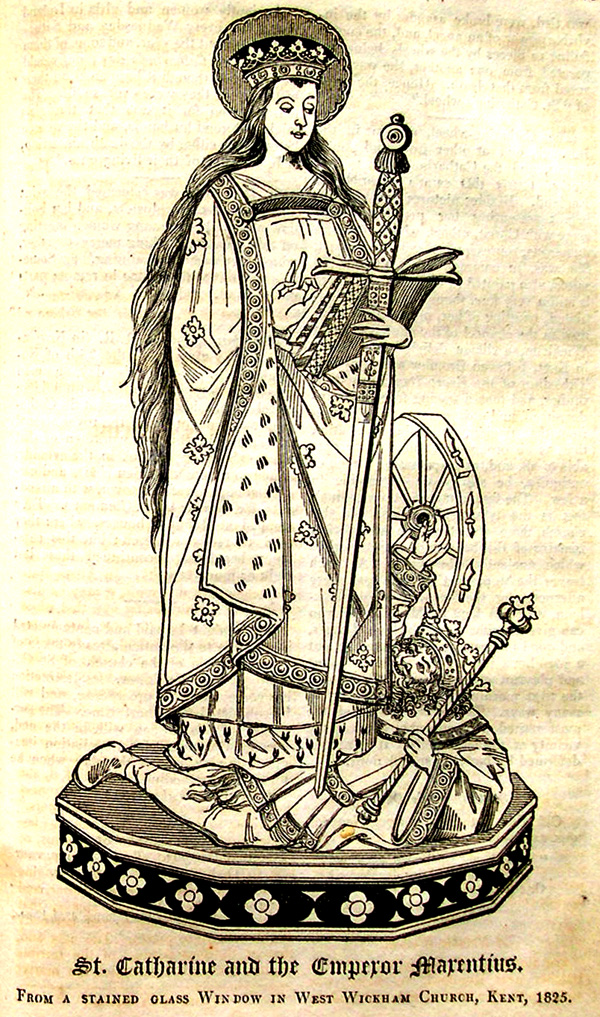

St. Catharine and the Emperor Marentius.

FROM A STAINED GLASS WINDOW IN WEST WICKHAM CHURCH, KENT, 1825.

was tied, were broke asunder by the invisible power of an angel, and, the engine falling to pieces by the wheels being separated from one another, she was delivered from death. Hence, the name of "St. Catharine's wheel."

The Catharine-wheel, a sign in the Borough, and at other inns and public houses, and the Catharine-wheel in fireworks, testify this saint's notoriety in England. Besides pictures and engravings representing her pretended marriage with Christ, others, which are more numerous, represent her with her wheel. She was, in common with other papal saints, also painted in churches, and there is still a very fine, though somewhat mutilated, painting of her, on the glass window in the chancel of the church of West Wickham, a village delightfully situated in Kent, between Bromley and Croydon. The editor of the Every-Day Book went thither, and took a tracing from the window itself, and now presents an engraving from that tracing, under the expectation that, as an ornament, it may be acceptable to all, and, as perpetuating a relic of antiquity, be still more acceptable to a few. The figure under St[.] Catharine's feet is the tyrant Maxentius. In this church there are other fine and perfect remains of the beautifully painted glass which anciently adorned it. A coach leaves the Ship, at Charing-cross, every afternoon for the Swan, at West Wickham, which is kept by Mr. Crittel, who can give a visiter a good bed, good cheer, and good information, and if need be, put a good horse into a good stable. A short and pleasant walk of a mile to the church the next morning will be gratifying in many ways. The village is one of the most retired and agreeable spots in the vicinity of the metropolis. It is not yet deformed by building speculations.

St. Catharine's Day.

Old Barnaby Googe, from Naogeorgus, says—

"What should I tell what sophisters

on Cathrins day devise?

Or else the superstitious toyes

that maisters exercise."Anciently women and girls in Ireland kept a fast every Wednesday and Saturday throughout the year, and some of them also on St. Catharine's day; nor would they omit it though it happened on their birthday, or they were ever so ill. The reason given for it was that the girls might get good husbands, and the women better ones, either by the death, desertion, or reformation of their living ones.*[1]

St. Catharine was esteemed the saint and patroness of spinsters, and her holiday observed by young women meeting on this day, and making merry together, which they call "Cathar'ning."[2]† Something of this still remains in remote parts of England.

Our correspondent R. R. (in November, 1825,) says, "On the 25th of November, St. Catharine's day, a man dressed in woman's clothes, with a large wheel by his side, to represent St. Catharine, was brought out of the royal arsenal at Woolwich, (by the workmen of that place,) about six o'clock in the evening, seated in a large wooden chair, and carried by men round the town, with attendants, &c. similar to St. Clement's. They stopped at different houses, where they used to recite a speech; but this ceremony has been discontinued these last eight or nine years."

Much might be said and contemplated in addition to the notice already taken of the demolition of the church of St. Catharine's, near the Tower. Its destruction has commenced, is proceeding, and will be completed in a short time. The surrender of this edifice will, in the end, become a precedent for a spoliation imagined by very few on the day when he utters this foreboding.

25th of November, 1825.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Sweet Butter-bur. Tussilago frgrans

Dedicated to St. Catharine.