October 7.

St. Mark, Pope, A. D. 336. Sts. Sergius and Bacchus. Sts. Marcellus and Apuleius. St. Justina of Padua, A. D. 304. St. Osith, A. D. 870.

Purveyance for Winter.

After the harvest for human subsistence during winter, most of the provision for other animals ripens, and those with provident instincts are engaged in the work of gathering and storing.

Perhaps the prettiest of living things in the forest are squirrels. They may now be seen fully employed in bearing off their future food; and now many of the little creatures are caught by the art of man; to be encaged for life to contribute to his amusement.

Squirrels and Hares.

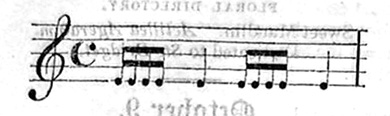

On a remark by the hon. Daines Barrington, that "to observe the habits and manners of animals is the most pleasing part of the study of zoology," a correspondent, in a letter to "Mr. Urban," says "I have for several years diverted myself by keeping squirrels, and have found in them not less variety of humours and dispositions than Mr. Cowper observed in his hares. I have had grave and gay, fierce and gentle, sullen and familiar, and tractable and obedient squirrels. One property I think highly worthy of observation, which I have found common to the species, as far as my acquaintance has been by no means confined to a few: yet this property has, I believe, never been adverted to by any zoological writer. I mean, that they have an exact musical ear. Not that they seem to give the least attention to any music, vocal or instrumental, which they hear; but they universally dance in their cages to the most exact time, striking the ground with their feet in a regular measured cadence, and never changing their tune without an interval of rest. I have known them dance perhaps ten minutes in allegro time of eight quavers in a bar, thus:

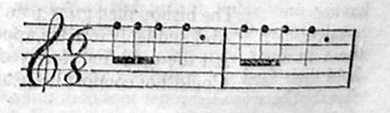

then, after a pause, they would change to the time of six quavers divided into three quavers and a dotted crotchet, thus:

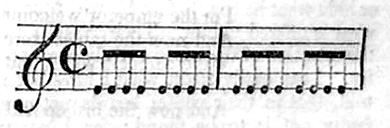

again, after a considerable rest, they would return to common time divided by four semiquavers, one crotchet, in a bar, thus:

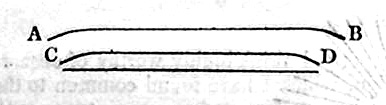

always continuing to dance or jump to the same tune for many minutes, and always resting before a change of tune. I once kept a male and a female in one large cage, who performed a peculiar dance together thus; the male jumped sideways, describing a portion of a circle in the air; the female described a portion of a smaller circle concentric with the first, always keeping herself duly under the male, performing her leap precisely in the same time, and grounding her feet in the same moment with him.

While the male moved from A to B, or from B to A, the female moved from C to D, or from D to C, and their eight feet were so critically grounded together, that they gave but one note. I must observe, that this practice of dancing seems to be an expedient to amuse them in their confinement; because, when they are for a time released from their cages, they never dance, but reserve this diversion until they are again immured."

Mr. Urban's correspondent continues thus, "no squirrel will lay down what he actually has in his paws, to receive even food which he prefers, but will always eat or hide what he has, before he will accept what is offered to him. Their sagacity in the selection of their food is truly wonderful. I can easily credit what I have been told, that in their winter hoards not one faulty nut is to be found; for I never knew them accept a single nut, when offered to them, which was either decayed or destitute of kernel: some they reject having only smelt them; but they seem usually to try them by their weight, poising them in their fore-feet. In eating, they hold their food not with their whole fore-feet, but between the inner toes or thumbs. I know not whether any naturalist has observed that their teeth are of a deep orange colour."

This gentleman, who writes late in the year 1788, proceeds thus, "A squirrel sits by me while I write this, who was born in the spring, 1781, and has been mine near seven years. He is, like Yorick, 'a whoreson mad fellow—a pestilent knave—a fellow of infinite jest and fancy.['] When he came to me, I had a venerable squirrel, corpulent, and unwieldy with age. The young one agreed well with him from their first introduction, and slept in the same cage with him; but he could never refrain from diverting himself with the old gentleman's infirmities. It was my custom daily to let them both out on the floor, and then to set the cage on a table, placing a chair near it to help the old squirrel in returning to his home. This was great exercise to the poor old brute; and it was the delight of the young rogue to frustrate his efforts, by suffering him to climb up one bar of the chair, then pursuing him, embracing him round the waist, and pulling him down to the ground; then he would suffer him to reach the second bar, or perhaps the seat of the chair, and afterwards bring him back to the floor as at first. All this was done in sheer fun and frolic, with a look and manner full of inexpressible archness and drollery. The old one could not be seriously angry at it; he never fought or scolded, but gently complained and murmured at his unlucky companion. One day, about an hour after this exercise, the old squirrel was found dead in his cage, his wind and his heart being quite broken by the mishievous wit of his young mess-mate. My present squirrel one day assaulted and bit me without any provocation. To break him of this trick, I pursued him some minutes about the room, stamping and scolding at him, and threatening him with my handkerchief. After this, I continued to let him out daily, but took no notice of him for some months. The coolness was mutual: he neither fled from me, nor attempted to come near me. At length I called him to me: it appeared that he had only waited for me to make the first advance; he threw off his gravity towards me, and ran up on my shoulder. Our reconciliation was cordial and lasting; he has never attempted to bite me since, and there appears no probablility of another quarrel between us, though he is every year wonderfully savage and ferocious at the first coming-in of filberts and walnuts. He is frequently suffered to expatiate in my garden; he has never of late attempted to wander beyond it; he always climbs up a very high ash tree, and soon after returns to his cage, or into the parlour."

For what this observant writer says of hares, see the 17th day of the present month.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Indian Chrysanthemum. Chrysanthemum Indicum.

Dedicated to St. Mark, Pope.