September 5.

St. Laurence Justinian, first Patriarch of Venice, A. D. 1455. St. Bertin, Abbot, A. D. 709. St. Alto, Abbot, 8th Cent.

Bartholomew Fair.

1825. On this day, Monday the 5th, the Fair was resumed, when the editor of the Every-Day Book accurately surveyed it throughout. From his notes made on the spot he reports the following particulars of what he there observed.

VISIT TO

Bartholomew Fair.

At ten o'clock this morning I entered Smithfield from Giltspur-street. [Mem. This way towards Smithfield was anciently called Gilt Spurre, or Knight-Riders Street, because of the knights, who in quality of their honour wore gilt spurs, and who, with others, rode that way to the tournaments, justings, and other feats of arms used in Smithfield.* [1]

On this day there were small uncovered stalls, from the Skinner-street corner of Giltspur-street, beginning with the beginning of the churchyard, along the whole length of the churchyard. On the opposite side of Giltspur-street there were like stalls, uncovered, from the Newgate-street corner, in front of the Compter-prison, in Giltspur-street. At these stalls were sold oysters, fruit, inferior kinds of cheap toys, common gingerbread, small wicker-baskets, and other articles of trifling value. They seemed to be mere casual standings, taken up by petty dealers, and chapmen in small ware, who lacked means to purchase room, and furnish out a tempting display. Their stalls were set out from the channel into the roadway. One man occupied upwards of twenty feet of the road lengthwise, with discontinued wood-cut pamphlets, formerly published weekly at twopence, which he spread out on the ground, and sold at a halfpenny each in great quantities; he also had large folio bible prints, at a halfpenny each, and prints from magazines at four a penny. The fronts of these standings were towards the passengers in the carriage-way. They terminated, as before observed, with the northern ends of St. Sepulchre's churchyard on one side, and the Compter on the other. Then, with occasional distances of three or four feet for footways, from the road to the pavement, began lines of covered stalls, with their open fronts opposite the fronts of the house, and close to the curb stone, and their enclosed backs in the road. On the St. Sepulchre's side, they extended to Cock-lane, from Cock-lane to the house of Mr. Blacket, clothier and mercer, at the Smithfield corner of Giltspur-street; then, turning the corner of his house into Smithfield, they continued to Hosier-lane, and from thence all along the west side of Smithfield to the Cow-lane corner, where, on that side, they terminated at that corner, in a line with the opposite corner leading to St. John-street, where the line was resumed, and ran thitherward to Smithfield-bars, and there on the west side ended. Crossing over to the east side, and returning south, these covered stalls commenced opposite to their termination on the west, and ran towards Smithfield, turning into which they ran westerly towards the pig-market, and from thence to Long-lane; from Long-lane, they ran along the east side of Smithfield to the great gate of Cloth-fair, and so from Duke-street, went on the south side, to the great front gate of Bartholomew-hospital, and from thence to the carriage entrance of the hospital, from whence they were continued along Giltspur-street to the Compter, where they joined the uncovered stalls before described. These covered stalls, thus surrounding Smithfield, belonged to dealers in gingerbread, toys, hardware, garters, pocket-books, trinkets, and articles of all prices, from a halfpenny to a half sovereign. The gingerbread stalls varied in size, and were conspicuously fine, from the dutch gold on their different shaped ware. The largest stalls were the toy-seller's; some of these had a frontage of five and twenty feet, and many of eighteen. The usual frontage of the stalls was eight, ten, and twelve feet; they were six feet six inches, or seven feet, high in front, and from four feet six inches, to five feet, in height at the back, and all formed of canvass, tightly stretched across light poles and railing; the canvass roofings, declined pent-house-ways to the backs, which were enclosed by canvass to the ground. The fronts, as before mentioned, were entirely open to the thronging passengers, for whom a clear way was preserved on the pavements between the fronts of the stalls and the fronts of the houses, all of which necessarily had their shutters up and their doors closed.

The shows of all kinds had their fronts towards the area of Smithfield, and their backs close against the backs of the stalls, without any passage between them in any part. There not being any shows or booths, save as thus described, the area of Smithfield was entirely open. Thus, any one standing in the carriage-way might see all the shows at one view. They surrounded and bounded Smithfield entirely, except on the north side, which small part alone was without shows, for they were limited to the other three sides; namely, Cloth-fair side, Bartholomew-hospital side, and Hosier-lane side. Against the pens in the centre, there were not any shows, but the space between the pens and the shows quite free for spectators, and persons making their way to the exhibitions. Yet, although no coach, cart, or vehicle of any kind, was permitted to pass, this immense unobstructed carriage-way was so thronged, as to be wholly impassable. Officers were stationed at the entrance of Giltspur-street, Hosier-lane, and Duke-street, to prevent carriages and horsemen from entering. The only ways by which they were allowed ingress to Smithfield at all, were through Cow-lane, Chick-lane, Smithfield-bars, and Long-lane; and then they were to go on, and pass without stopping, through one or other of these entrances, and without turning into the body of the Fair, wherein were the shows. Thus the extent of carriage-way was bounded from Cow-lane to Long-lane, in a right line, nor were carriages or horses suffered to stand or linger, but the riders or drivers were compelled to go about their business, if business they had, or to alight for their pleasure, and enter the Fair, if they came thither in search of pleasure. So was order so far preserved; and the city officers, to whom was comitted the power of enforcing it, exercised their duty rigorously, and properly; because, to their credit, they swerved not from their instructions, and did not give just cause of offence to any whom the regulations displeased.

The sheep-pens occupying the area of Smithfield, heretofore the great public cookery at Fair times, was this day resorted to by boys and others in expectation of steaming abundance; nor were they disappointed. The pens immediately contiguous to the passage through them from Bartholomew-hospital-gate towards Smithfield-bars, were not, as of old, decked out and denominated, as they were within recollection, with boughs and inscriptions tempting hungry errand boys, sweeps, scavengers, dustmen, drovers, and bullock-hankers to the "princely pleasures" within the "Brighton Pavilion," the "Royal Eating Room," "Fair Rosamond's Bower," the "New London Tavern," and the "Imperial Hotel:" these names were not:—nor were there any denominations; but there was sound, and smell, and sight, from sausages almost as large as thumbs, fried in miniature dripping-pans by old women, over fires in saucepans; and there were oysters, which were called "fine and fat," because their shells were as large as tea saucers. Cloths were spread on tables or planks, with plates, knives and forks, pepper and salt, and, above all, those alluring condiments to persons of the rank described, mustard and vinegar. Here they came in crowds; each selecting his table-d'-hote, dined handsomely for threepence, and sumptuously for fourpence. The purveyors seemed aware of the growing demand for cleanliness of appearance, and whatever might be the quality of the viands, they were served up in a more decent way than many of the consumers were evidently accustomed to. Some of them seemed appalled by being in "good company," and handled their knives and forks in a manner which bespoke the embarrassment of "dining in public" with such implements.

My object in going to Bartholomew Fair was to observe its present state, and record it as I witnessed it in the Every-Day Book. I therefore first took a perambulatory view of the exterior, from Giltspur-street, and keeping to the left, went completely round Smithfield, on the pavement, till I returned to the same spot; from thence I ventured "to take the road" in the same direction, examined the promising show-cloths and inscriptions on each show, and shall now describe or mention every show in the Fair. It may be more interesting to read some years hence than now. Feeling that our ancestors have slenderly acquainted us with what was done here in their time, and presuming that our posterity may cultivate the "wisdom of looking backward" in some degree, as we do with the higher wisdom of "looking forward," I write as regards Bartholomew Fair, rather to amuse the future, than to inform the present, generation.

SHOW I.

This was the first show, and stood at the corner of Hosier-lane. The inscription outside, painted in black letters, a little more than an inch in height, on a piece of white linen, was as follows:—

"Murder of Mr. Weare, and Probert's cottage.—The Execution of William Probert.

"A View to be seen here of the Visit of Queen Sheba to King Soloman on the Throne.—Daniel in the Den of Lions.—St. Paul's Conversion.—The Tower of Babel.—The Greenland Whale-Fishery.—The Battle of Waterloo.—A View of the City of Dublin.—Coronation of George IV."

This was what is commonly, but erroneously called a puppet-show; it consisted of scenes rudely painted, successively let down by strings pulled by the showman; and was viewed through eye-glasses of magnifying power, the spectators standing on the ground. A green curtain from a projecting rod was drawn round them while viewing. "Only a penny—only a penny," cried the showman; I paid my penny, and saw the first and the meanest show in the Fair.

SHOW II.

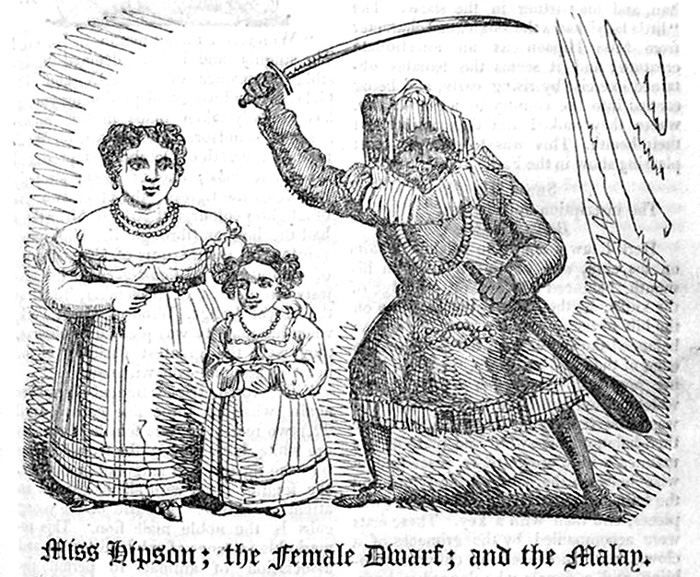

"Only a penny—only a penny, walk up—pray walk up." So called out a man with a loud voice, on an elevated stage, while a long drum and hurdy-gurdy played away; I complied with the invitation, and went in to see what the show-cloths described, "MISS HIPSON, the Middlesex Wonder; the Largest Child in the Kingdom, when young the Handsomest Child in the World.—The Persian Giant.—The Fair Circassian with Silver Hair.—The Female Dwarf, Two Feet, Eleven Inches high.—Two Wild Indians from the Malay Islands in the East," and other wonders. One of these "Wild Indians" had figured outside the show, in the posture represented in the engraving; in that position he was sketched by an artist who accompanied me into the show, and who there drew the "little lady" and the "gigantic child," Miss Hipson.

Miss Hipson; the Female Dwarf; and the Malay.

When a company had collected, they were shown from the floor of a caravan on wheels, one side whereof was taken out, and replaced by a curtain, which was either drawn to, or thrown back as occasion required. After the audience had dispersed, I was permitted by the proprietor of the show, Nicholas Maughan, of Ipswich, Suffolk, to go "behind the curtain," where the artist completed his sketches, while I entered into conversation with the persons exhibited. Miss Hipson, only twelve years of age, is remarkably gigantic, or rather corpulent, for her age, pretty, well-behaved, and well-informed; she weighed sixteen stone a few months before, and has since increased in size; she has ten brothers and sisters, nowise remarkable in appearance: her father, who is dead, was a bargeman at Brentford. The name of the "little lady" is Lydia Walpole, she was born at Addiscombe, near Yarmouth, and is sociable, agreeable, and intelligent. The fair Circassian is of pleasing countenance and manners. The Persian giant is a good-natured, tall, stately negro. The two Malays could not speak English, except, however, three words, "drop o' rum," which they repeated with great glee. One of them, with long hair reaching below the waist, exhibited the posture of drawing a bow; Mr. Maughan described them as being passionate, and showed me a severe wound on his finger which the little one, in the engraving, had given him by biting, while he endeavoured to part him and his countryman , during a quarrel a few days ago. A "female giant" was one of the attractions to this exhibition, but she could not be shown for illness: Miss Hipson described her to be a very good young woman.

There was an appearance of ease and good condition, with content of mind, in the persons composing this show, which induced me to put several questions to them, and I gathered that I was not mistaken in my conjecture. They described themselves as being very comfortable, and that they were taken great care of, and well treated by the proprietor, Mr. Maughan, and his partner in the show. The "little lady" had a thorough good character from Miss Hipson as an affectionate creature; and it seems the females obtained exercise by rising early, and being carried into the country in a post-chaise, where they walked and thus maintained their health. This was to me the most pleasing show in the Fair.

SHOW III.

The inscription outside was,

Ball's Theatre.

Here I saw a man who balanced chairs on his chin, and holding a knife in his mouth, balanced a sword on the edge of the knife; he then put a pewter plate on the hilt of the sword horizontally, and so balanced the sword with the plate on the edge of the knife as before, the plate having previously received a rotary motion, which it communicated to the sword and was preserved during the balancing. He then balanced the sword and plate in like manner, with a crown-piece placed edgewise between the point of the sword and the knife, and afterwards with two crown-pieces, and then with a key. These feats were accompanied by the grimaces of a clown, and succeeded by children tumbling, and a female who danced a horn-pipe. A learned horse found out a lady in the company who wished to be married; a gentleman who preferred a quart of beer to going to church to hear a good sermon; a lady who liked to lie abed in the morning; and made other discoveries which he was requested to undertake by his master in language not only "offensive to ears polite," but to common decency. The admission to this show was a penny.

SHOW IV.

Atkin's Menagerie.

This inscription was in lamps on one of the largest shows in the fair. The display of show-cloths representing some of the animals exhibited within, reached about forty feet in height, and extended probably the same width. The admission was sixpence. As a curiosity, and because it is a singularly descriptive list, the printed bill of the show is subjoined.

"MORE WONDERS IN

ATKINS'S ROYAL MENAGERIE."Under the Patronage of HIS MAJESTY.

"Wonderful Phenomenon in Nature! The singular and hitherto deemed impossible occurrence of a LION and TIGRESS cohabiting and producing young, has actually taken place in this menagerie, at Windsor. The tigress, on Wednesday, the 27th of October last, produced three fine cubs; one of them strongly resembles the tigress; the other two are of a lighter colour, but striped. Mr. Atkins had the honour (through the kind intervention of the marquis of Conyngham,) of exhibiting the lion-tigers to his majesty, on the first of November, 1824, at the Royal Lodge, Windsor Great Park, when his majesty was pleased to observe, they were the greatest curiosity of the beast creation he ever witnessed.

"The royal striped Bengal Tigress has again whelped three fine cubs, (April 22,) two males and one female: the males are white, but striped; the female resembles the tigress, and singular to observe, she fondles them with all the care of an attentive mother. The sire of the young cubs is the noble male lion. This remarkable instance of subdued temper and association of animals to permit the keeper to enter their den, and introduce their young to the spectators, is the greatest phenomenon in natural philosophy.

"That truly singular and wonderful animal, the AUROCHOS. Words can only convey but a very confused idea of this animal's shape, for there are few so remarkably formed. Its head is furnished with two large horns, growing from the forehead, in a form peculiar to no other animal; from the nostrils to the forehead, is a stiff tuft of hair, and underneath the jaw to the neck is a similar brush of hair, and between the forelegs is hair growing about a foot and a half long. The mane is like that of a horse, white, tinged with black, with a beautiful long flowing white tail; the eye remarkably keen, and as large as the eye of the elephant: colour of the animal, dark chestnut; the appearance of the head, in some degree similar to the buffalo, and in some part formed like the goat, the hoof being divided; such is the general outline of this quadruped, which seems to partake of several species. This beautiful animal was brought over by captain White, from the south of Africa, and landed in England, September 20, 1823, and is the same animal so frequently mistaken by travellers for the unicorn: further to describe its peculiarities would occupy too much space in a handbill. The only one in England.

"That colossal animal, the wonderful performing

Elephant,

Upwards of ten feet high!!—Five tons weight!! His consumption of hay, corn, straw, carrots, water, &c., exceeds 800lbs. daily. The elephant, the human race excepted, is the most respectable of animals. In size, he surpasses all other terrestrial creatures, and by far exceeds any other travelling animal in England. He has ivory tusks, four feet long, one standing out on each side of his trunk. His trunk serves him instead of hands and arms, with which he can lift up and seize the smallest as well as the largest objects. He alone drags machines which six horses cannot move. To his prodigious strength, he adds courage, prudence, and an exact obedience. He remembers favours as long as injuries: in short, the sagacity and knowledge of this extraordinary animal are beyond any thing human imagination can possibly suggest. He will lie down and get up at the word of command, notwithstanding the many fabulous tales of their having no joints in their legs. He will take a sixpence from the floor, and place it in a box he has in the caravan; bolt and unbolt a door; take his keeper's hat off, and replace it; and by the command of his keeper will perform so many wonderful tricks, that he will not only astonish and entertain the audience, but justly prove himself the half-reasoning beast. He is the only elephant now travelling.

"A full grown LION and LIONESS, with four cubs, produced December 12, 1824, at Cheltenham.

"Male Bengal Tiger. Next to the lion, the tiger is the most tremendous of the carnivorous class; and whilst he possesses all the bad qualities of the former, seems to be a stranger to the good ones: to pride, to strength, to courage, the lion adds greatness, and sometimes, perhaps, clemency; while the tiger, without provocation, is fierce—without necessity, is cruel. Instead of instinct, he hath nothing but a uniform rage, a blind fury; so blind, indeed, so undistinguishing, that he frequently devours his own progeny; and if the tigress offers to defend them, he tears in pieces the dam herself.

"The Onagra, a native of the Levant, the eastern parts of Asia, and the northern parts of Africa. This race differs from the zebra by the size of the body, (which is larger,) slenderness of the legs, and lustre of the hair. The only one now alive in England.

"Two Zebras, one full grown, the other in its infant state, in which it seems as if the works of art had been combined with those of nature in this wonderful production. In symmetry of shape, and beauty of colour, it is the most elegant of all quadrupeds ever presented; uniting the graceful figure of a horse, with the fleetness of a stag: beautifully striped with regular lines, black and white.

"A Nepaul Bison, only twenty-four inches high.

"Panther, or spotted tiger of Buenos Ayres, the only one travelling.

"A pair of rattle-tail Porcupines.

"Striped untameable Hyæna, or tiger wolf.

"An elegant Leopard, the handsomest marked animal ever seen.

"Spotted Laughing Hyæna, the same kind of animal described never to be tamed; but singular to observe, it is perfectly tame, and its attachment to a dog in the same den is very remarkable.

"The spotted Cavy.

"Pair of Jackalls.

"Pair of interesting Sledge Dogs, brought over by captain Parry from one of the northern expeditions: they are used by the Esquimaux to draw the sledges on the ice, which they accomplish with great velocity.

"A pair of Rackoons, from North America.

"The Oggouta, from Java.

"A pair of Jennetts, or wild cats.

"The Coatimondi, or ant-eater.

"A pair of those extraordinary and rare birds, PELICANS of the wilderness. The only two alive in the three kingdoms. — These birds have been represented on all crests and coats of arms, to cut their breasts open with the points of their bills, and feed their young with their own blood, and are justly allowed by all authors to be the greatest curiosity of the feathered tribe.

"Ardea Dubia, or adjutant of Bengal, gigantic emew, or Linnæus's southern ostrich. The peculiar characteristics that distinguish this bird from the rest of the feathered tribe;—it comes from Brazil, in the new continent; it stands from eight to nine feet high when full grown; it is too large to fly, but is capable o. [sic] out-running the fleetest horses of arabia; what is still more singular, every quill produces two feathers. The only one travelling.

"A pair of rapacious Condor-Minors, from the interior of South America, the largest birds of flight in the world when full grown; it is the same kind of bird the Indians have asserted to carry off a deer or young calf in their talons, and two of them are sufficient to destroy a buffalo, and the wings are as much as eighteen feet across.

"The great Horned Owl of Bohemia. Several species of gold and silver pheasants, of the most splendid plumage, from China and Peru. Yellow-crested cockatoo. Scarlet and buff macaws.—Admittance to see the whole menagerie, 1s.—Children, 6d.—Open from ten in the forenoon till feeding-time, half-past-nine, 2s."

Here ends Atkins's bill; which was plentifully stuck against the outside, and the people "tumbled up" in crowds, to the sound of clarionets, trombones, and a long drum, played by eight performers in scarlet beef-eater coats, with wild-skin caps, who sat fronting the crowd, while a stentorian showman called out "don't be deceived; the great performing elephant—the only lion and tigress in one den that are to be seen in the Fair, or the proprietor will forfeit a thousand guineas! Walk in! walk in!" I paid my sixpence, and certainly the idea of the exhibition raised by the invitation and the programme, was in no respect overcharged. The "menagerie" was thoroughly clean, and the condition of the assembled animals, told that they were well taken care of. The elephant, with his head through the bars of his cage, whisked his proboscis diligently in search of eatables from the spectators, who supplied him with fruit or biscuits, or handed him halfpence, which he uniformly conveyed by his trunk to a retailer of gingerbread, and got the money's-worth in return. Then he unbolted the door to let in his keeper, and bolted it after him; took up a six-pence with his trunk, lifted the lid of a little box fixed against the wall and deposited it within it, and some time afterwards relifted the lid, and taking out the sixpence with a single motion, returned it to the keeper; he knelt down when told, fired off a blunderbuss, took off the keeper's hat, and afterwards replaced it on his head with as fitting propriety as the man's own hand could have done; in short, he was perfectly docile, and performed various feats that justified the reputation of his species for high understanding. The keeper showed every animal in an intelligent manner, and answered the questions of the company readily and with civility. His conduct was rewarded by a good parcel of half-pence, when his hat went round with a hope, that "the ladies and gentlemen would not forget the keeper before he showed the lion and the tigress." The latter was a beautiful young animal, with two playful cubs about the size of bulldogs, but without the least fierceness. When the man entered the den, they frolicked and climbed about him like kittens; he took them up in his arms, bolted them in a back apartment, and after playing with the tigress a little, threw back a partition which separated her den from the lion's, and then took the lion by the beard. This was a noble animal; he was couching, and being inclined to take his rest, only answered the keeper's command to rise, by extending his whole length, and playfully putting up one of his magnificent paws, as a cat does when in a good humour. The man then took a short whip, and after a smart lash or two upon his back, the lion rose with a yawn, and fixed his eye on his keeper with a look that seemed to say — "Well, I suppose I must humour you." The man then sat down at the back of the den, with his back against the partition, and after some ordering and coaxing, the tigress sat on his right hand, and the lion on his left, and all three being thus seated, he threw his arms round their necks, played with their noses, and laid their heads in his lap. He arose and the animals with him; the lion stood in a fine majestic position, but the tigress reared, and putting one foot over his shoulder, and patting him with the other, as if she had been frolicking with one of her cubs, he was obliged to check her playfulness. Then by coaxing, and pushing him about, he caused the lion to sit down, and while in that position opened the animal's ponderous jaws with his hands, and thrust his face down into the lion's throat, wherein he shouted, and there held his head nearly a minute. After this he held up a common hoop for the tigress to leap through, and she did it frequently. The lion seemed more difficult to move to this sport. He did not appear to be excited by command or entreaty; at last, however, he went through the hoop, and having been once roused, repeated the action several times; the hoop was scarcely two feet in diameter. The exhibition of these two animals concluded by the lion lying down on his side, when the keeper stretched himself to his whole length upon him, and then calling to the tigress she jumped upon the man, extended herself with her paws upon his shoulders, placed her face sideways upon his, and the whole three lay quiescent till the keeper suddenly slipped himself off the lion's side, with the tigress on him, and the trio gambolled and rolled about on the floor of the den, like playful children on the floor of a nursery.

Of the beasts there is not room to say more, than that their number was surprising, considering that they formed a better selected collection and showed in higher condition from cleanliness and good feeding, than any assemblage I ever saw. Their variety and beauty, with the usual accessory of monkeys, made a splendid picture. The birds were equally admirable, especially the pelicans, and the emew. This sixpenny "show" would have furnished a dozen sixpenny "shows," at least, to a "Bartlemy Fair" twenty years ago.

SHOW V.

This was a mare with seven feet, in a small temporary stable in the passage-way from the road to the foot-pavement, opposite the George Inn, and adjoining to the next show: the admission to this "sight" was threepence. The following is a copy of the printed bill:—

"To Sportsmen and Naturalists.—Now exhibiting, one of the greatest living natural curiosities in the world; namely, a thorough-bred chesnut MARE, with seven legs! four years of age, perfectly sound, free from blemish, and shod on six of her feet. She is very fleet in her paces, being descended from that famous hourse Julius Cæsar, out of a thorough-bred race mare descended from Eclipse, and is remarkably docile and temperate. She is the property of Mr. T. Checketts, of Balgrave-hall, Leicestershire; and will be exhibited for a few days as above."

This mare was well worth seeing. Each of her hind legs, besides its natural and well-formed foot, had another growing out from the fetlock joint: one of these additions was nearly the size of the natural foot; the third and least grew from the same joint of the fore-leg. Mr. Andrews, the proprietor, said, that they grew slowly, and that the new hoofs were, at first, very soft, and exuded during the process of growth. This individual, besides his notoriety from the possession of this extraordinary mare, attained further distinction by having prosecuted to conviction, at the Warwick assizes, in August, 1825, a person named Andrews, for swindling. He complained bitterly of the serious expense he had incurred in bringing the depredator to justice; his own costs, he said, amounted to the sum of one hundred and seventy pounds.

SHOW VI.

Richardson's Theatre.

The outside of this show was in height upwards of thirty feet, and occupied one hundred feet in width. The platform on the outside was very elevated; the back of it was lined with green baize, and festooned with deeply-fringed crimson curtains, except at two places where the money-takers sat, which were wide and roomy projections, fitted up like gothic shrine-work, with columns and pinnacles. There were fifteen hundred variegated illumination-lamps disposed over various parts of this platform, some of them depending from the top in the shape of chandeliers and lustres, and others in wreaths and festoons. A band of ten performers in scarlet dresses, similar to those worn by beef-eaters, continually played on clarionets, violins, trombones, and the long drum; while the performers paraded in their gayest "properties" before the gazing multitude. Audiences rapidly ascended on each performance being over, and paying their money to the receivers in their gothic seats, had tickets in return; which, being taken at the doors, admitted them to descend into the "theatre." The following "bill of the play" was obtained at the doors upon being requested:—

* * * Change of Performance each Day.

RICHARDSON'S

THEATRE.

This Day will be performed, an entire New

Melo-Drama, called theWANDERING

OUTLAW,

Or, the Hour of Retribution.Gustavus, Elector of Saxony, Mr. Wright.

Orsina, Baron of Holstein, Mr. Cooper.

Ulric and Albert, Vassals to Orsina,

Messrs. Grove and Moore.

St. Clair, the Wandering Outlaw, Mr. Smith.

Rinalda, the Accusing Spirit, Mr. Darling.

Monks, Vassals, Hunters, &c.

Rosabella, Wife to the Outlaw, Mrs. Smith.

Nuns and Ladies.

The Piece concludes with the DEATH OF

ORSINA, and the Appearance of the

ACCUSING SPIRIT.

The Entertainments to conclude with a New

Comic Harlequinade, with New Scenery,

Tricks, Dresses, and Decorations, called,HARLEQUIN

FAUSTUS!OR, THE

DEVIL WILL HAVE HIS OWN.

Luciferno, Mr. Thomas.

Dæmon Amozor, afterwards Pantaloon, Mr. WILKINSON.—DæZiokos, afterwards Clown, Mr. HAYWARD.—Violencello Player, Mr. HARTEM.—Baker, Mr. THOMPSON.—Landlord, Mr. WILKINS.—Fisherman, Mr. RAE.—Doctor Faustus, afterwards Harlequin, Mr. SALTER.

Adelada, afterwards Columbine,

Miss WILMOT.Attendant Dæmons, Sprites, Fairies, Bal-

lad Singers, Flower Girls, &c. &c.

The Pantomime will finish with

A SPLENDID PANORAMA,

Painted by the First Artists.

BOXES, 2s. PIT, 1s. GALLERY, 6d.

The theatre was about one hundred feet long, and thirty feet wide, hung all round with green baize, and crimson festoons. "Ginger beer, apples, nuts, and a bill of the play," were cried; the charge for a bill to a person not provided with one was "a penny." The seats were rows of planks, rising gradually from the ground at the end, and facint the stage, without any distinction of "boxes, pit, or gallery." The stage was elevated, and there was a painted proscenium like that in a regular theatre, with a green curtain, and the king's arms above, and an orchestra lined with crimson cloth, and five violin-players in military dresses. Between the orchestra and the bottom row of seats, was a large space, which, after the seats were filled, and greatly to the discomfiture of the lower seat-holders, was nearly occupied by spectators. There were at least a thousand persons present.

The curtain drew up and presented the "Wandering Outlaw," with a forest scene and a cottage; the next scene was a castle; the third was another scene in the forest. The second act commenced with a scene of an old church and a marketplace. The second scene was a prison, and a ghost appeared to the tune of the "evening hymn." The third scene was the castle that formed the second scene in the first act, and the performance was here enlivened by a murder. The fourth scene was rocks, with a cascade, and there was a procession to an unexecuted execution; for a ghost appeared, and saved the "Wandering Outlaw" from a fierce-looking headsman, and the piece ended. Then a plump little woman sung, "He loves and he rides away," and the curtain drew up to "Harlequin Faustus," wherein, after columbine and a clown, the most flaming character was the devil, with a red face and hands, in a red Spanish mantle and vest, red "continuations," stockings and shoes ditto to follow, a red Spanish hat and plume above, and a red "brass bugle horn." As soon as the fate of "Faustus" was concluded, the sound of a gong announced the happy event, and these performances were, in a quarter of an hour, repreated to another equally intelligent and brilliant audience.

SHOW VII.

ONLY A PENNY.

There never was such times, indeed!

NERO

The largest Lion in the Fair for a Hun-

dred Guineas!These inscriptions, with figured show-clothes, were in front of a really good exhibition of a fine lion, with leopards, and various other "beasts of the forest." They were mostly docile and in good condition. One of the leopards was carried by his keeper a pick-a-back. Such a show for "only a penny" was astonishing.

SHOW VIII.

"SAMWELL'S COMPANY."

Another penny show: "The Wonderful Children on the tight Rope, and Dancing Horse, Only a Penny!" I paid my penny to the money-taker, a slender "fine lady," with three feathers in a "jewelled turban," and a dress of blue and white muslin and silver; and withinside I saw the "fat, contented, easy" proprietor, who was arrayed in corresponding magnificence. If he loved leanness, it was in his "better half," for himself had none of it. Obesity had disqualified him for activity, and therefore in his immensely tight and large satin jacket, he was, as much as possible, the active commander of his active performers. He superintended the dancing of a young female on the tight rope. Then he announced, "A little boy will dance a hornpipe on the rope," and he ordered his "band" inside to play; this was obeyed without difficulty, for it merely consisted of one man, who blew a hornpipe tune on a Pan's-pipe; while it went on, the "little boy" danced on the tight rope; so far it was a hornpipe dance and no farther. "The little boy will stand on his head on the rope," said the manager, and the little boy stood on his head accordingly. Then another female danced on the slack-wire; and after her came a horse, not a "dancing horse," but a "learned" horse, quite as learned as the horse at Ball's theatre, in Show III. There was enough for "a penny."

SHOW IX.

"CLARKE FROM ASTLEY'S"

This was a large show, with the back against the side of "Samwell's Company," and its front in a line with Hosier-lane, and therefore looking towards Smithfield-bars. Large placards were pasted at the side, with these words, "CLARKE'S FROM ASTELY'S, Lighted with Real Gas, In and Outside." The admission to this show was sixpence. The platform outside was at least ten feet high, and spacious above, and here there was plenty of light. The interior was very large, and lighted by only a single hoop, about two feet six inches in diameter, with little jets of gas about an inch and a half apart. A large circle or ride was formed on the ground. The entertainment commenced by a man dancing on the tight-rope. The rope was removed, and a light bay horse was mounted by a female in trowsers, with a pink gown fully frilled, flounced, and ribboned, with the shoulders in large puffs. While the horse circled the ring at full speed, she danced upon him, and skipped with a hoop like a skipping-rope; she performed other dexterous feats, and concluded by dancing on the saddle with a flag in each hand, while the horse flew round the ring with great velocity. These and the subsequent performances were enlivened by tunes from a clarionet and horn, and jokes from a clown, who, when she had concluded, said to an attendant, "Now, John, take the horse off, and whatever you do, rub him well down with a cabbage." Then a man rode and danced on another horse, a very fine animal, and leaped from him three times over garters, placed at a considerable height and width apart, alighting on the horse's back while he was going round. This rider was remarkably dexterous. In conclusion, the clown got up and rode with many antic tricks, till, on the sudden, an apparently drunken fellow rushed from the audience into the ring, and began to pull the clown from the horse. The manager interfered, and the people cried—"Turn him out;" but the man persisted, and the clown getting off, offered to help him up, and threw him over the horse's back to the ground. At length the intruder was seated, with his face to the tail, though he gradually assumed a proper position; and riding as a man thoroughly intoxicated would ride, fell off; he then threw off his hat and great coat, and threw off his waistcoat, and then an under-waistcoat, and a third, and a fourth, and more than a dozen waistcoats. Upon taking off the last, his trowsers fell down and he appeared in his shirt; whereupon he crouched, and drawing his shirt off in a twinkling, appeared in a handsome fancy dress, leaped into the saddle of the horse, rode standing with great grace, received great applause, made his bow, and so the performance concluded.

This show was the last in the line on the west side of Smithfield.

SHOW X.

The line of shows on the east of Smithfield, commencing at Long-lane, began with "The Indian Woman—Chinese Lady and Dwarf," &c. A clown outside cried, "Be assured they're alive—only one penny each." The crowd was great, and the shows to be seen were many, I therefore did not go in.

SHOW XI.

On the outside was inscribed, "To be seen alive! The Prodigies of Nature!—The Wild Indian Woman and Child, with her Nurse from her own country.—The Silver-haired Lady and Dwarf. Only a Penny."—The showmaster made a speech: "Ladies and gentlemen, before I show you the wonderful prodigies of nature, let me introduce you to the wonderful works of art;" and then he drew a curain, where some wax-work figures stood. "This," said he, "ladies and gentlemen, is the famous old Mother Shipton; and here is the unfortunate Jane Shore, the beautiful mistress of king Edward the Second; next to her is his majesty king George the Fourth of most glorious memory; and this is queen Elizabeth in all her glory; then here you have the princess Amelia, the daughter of his late majesty, who is dead; this is Mary, queen of Scots, who had her head cut off; and this is O'Bryen, the famous Irish giant; this man, here, is Thornton, who was tried for the murder of Mary Ashford; and this is the exact resemblance of Othello, the moor of Venice, who was a jealous husband, and depend upon it every man who is jealous of his wife, will be as black as that negro. Now, ladies and gentlemen, the two next are a wonderful couple, John and Margaret Scott, natives of Dunkeld, in Scotland; they lived about ninety years ago; John Scott was a hundred and five years old when he died, and Margaret lived to be a hundred and twelve; and what is more remarkable, there is not a soul living can say he ever heard them quarrel." Here he closed the curtain, and while undrawing another, continued thus: "Having shown you the dead, I have now to exhibit to your two of the most extraordinary wonders of the living; this," said he, "is the widow of a New Zealand Chief, and this is the little old woman of Bagdad; she is thirty inches high, twenty-two years of age, and a native of Boston, in Lincolnshire." Each of these living subjects was quite as wonderful as the waxen ones: the exhibition, which lasted about five minutes, was ended by courteous thanks for the "approbation of the ladies and gentlemen present," and an evident desire to hurry them off, lest they might be more curious than his own curiosities.

SHOW XII.

"Only a penny" was the price of admission to "The Black Wild Indian Woman.—The White Indian Youth—and the welsh Dwarf.—All Alive!" There was this further announcement on the outside, "The Young American will Perform after the Manner of the French Jugglers at Vauxhall Gardens, with Balls, Rings, Daggers," &c. When the "Welsh dwarf" came on he was represented to be Mr. William Phillips, of Denbigh, fifteen years of age. The "white Indian youth" was an Esquimaux, and the exhibitor assured the visitors upon his veracity, that "the black wild Indian woman" was "a court lady of the island of Madagascar." The exhibitor himself was "the young American," an intelligent and clever youth in a loose striped jacket or frock tied round the middle. He commenced his performances by throwing up three balls, which he kept constantly in the air, as he afterwards did four, and then five, with great dexterity, using his hands, shoulders, and elbows, apparently with equal ease. He afterwards threw up three rings, each about four inches in diameter, and then four, which he kept in motion with similar success. To end his performance he produced three knives, which, by throwing up and down, he contrived to preserve in the air altogether. These feats reminded me of the Anglo-Saxon Glee-man, who "threw three balls and three knives alternately in the air, and caught them, one by one, as they fell; returning them again in regular rotation."* [2] The young American's dress and knives were very similar to the Glee-man's, as Strutt has figured them from a MS. in the Cotton collection. This youth's was one of the best exhibitions in the Fair, perhaps the very best. The admission it will be remembered was "only a penny."

SHOW XIII.

The inscriptions and paintings on the outside of this show were, "The White Negro, who was rescued from her Black Parents by the bravery of a British Officer—the only White Negro Girl Alive.—the Great Giantess and Dwarf.—Six Curiosities Alive!—only a Penny to see them All Alive!" While waiting a few minutes till the place filled, I had leisure to observe that one side of the place was covered by a criminal attempt to represent a tread-mill, in oil colours, and the operators at work upon it, superintended by gaolers, &c. On the other side were live monkies in cages; an old bear in a jacket, and sundry other animals. Underneath the wheels of the machine, other living creatures were moving about, and these turned out to be the poor neglected children of the showman and his wife. The miserable condition of these infants, who were puddling in the mud, while their parents outside were turning a bit of music, and squalling and bawling with all their might, "walk in—only a penny," to get spectators of the objects that were as yet concealed on their "proud eminence," the caravan, by a thin curtain, raised a gloom in the mind. I was in a reverie concerning these beings when the curtain was withdrawn, and there stood confessed to sight, she whom the showman called "the tall lady," and "the white negro, the greatest curiosity ever seen—the first that has been exhibited since the reign of George the Second—look at her head and hair, ladies and gentlemen, and feel it; there's no deception, it's like ropes of wool." There certainly was not any deception. The girl herself, who had the flat nose, thick lips, and peculiarly shaped scull of the negro, stooped to have her head examined, and being close to her I felt it. Her hair, if it could be called hair, was of a dirtyish flaxen hue; it hung in ropes, of a clothy texture, the thickness of a quill, and from four to six inches in length. Her skin was the colour of an European's. Afterwards stepped forth a little personage about three feet high, in a military dress, with top boots, who strutted his tiny legs, and held his head aloft with not less importance than the proudest general officer could assume upon his promotion to the rank of field-martial. Mr. Samuel Williams, whose versatile and able pencil has frequently enriched this work, visited the Fair after me, and was equally struck by his appearance. He favours me with the subjoined engraving of this

Little Man.

I took my leave of this show pondering on "the different ends our fates assign," but the jostling of a crowd in Smithfield, and the clash of instruments, were not favourable to musing, and I walked into the next.

SHOW XIV.

BROWN'S GRAND TROOP,

FROM PARIS.This was "only a penny" exhibition, notwithstanding that it elevated the king's arms, and bore a fine-sounding name. The performance began by a clown going round and whipping a ring; that is, making a circular space amongst the spectators with a whip in his hand to force the refractory. This being effected, a conjurer walked up to a table and executed several tricks with cups and balls; giving a boy beer to drink out of a funnel, making him blow through it to show that it was empty, and afterwards applying it to each of the boy's ears, from whence, through the funnel, the beer appeared to reflow, and poured on the ground. Afterwards girls danced on the single and double slack wire, and a melancholy looking clown, among other things, said they were "as clever as the barber and blacksmith who shaved magpies at twopence a dozen." The show concluded with a learned horse.

SHOW XV.

Another, and a very good menagerie—the admission "only a penny!" It was "GEORGE BALLARD'S Caravan," with "The Lioness that attacked the Exeter mail.—The great Lion.—Royal Tiger.—Large White Bear.—Tiger Owls," with monkies, and other animals, the usual accessories to the interior of a managerie [sic].

The chief attraction was "The Lioness." Her attack on the Exeter Mail was on a Sunday evening, in the year 1816. The coach had arrived at Winderslow-hut, seven miles on the London side of Salisbury. In a most extraordinary manner, at the moment when the coachman pulled up to deliver his bags, one of the leaders was suddenly seized by some ferocious animal. This produced a great confusion and alarm; two passengers who were inside the mail got out, ran into the house, and locked themselves up in a room above stairs; the horses kicked and plunged violently, and it was with difficulty the coachman could prevent the carriage from being overturned. It was soon perceived by the coachman and guard, by the light of the lamps, that the animal which had seized the horse was a huge lioness. A large mastiff dog came up and attacked her fiercely, on which she quitted the horse and turned upon him. The dog fled, but was pursued and killed by the lioness, within forty yards of the place. It appears that the beast had escaped from its caravan which was standing on the road side with others belonging to the proprietors of the menagerie, on their way to Salisbury Fair. An alarm being given, the keepers pursued and hunted the lioness into a hovel under a granary, which served for keeping agricultural implements. About half-past eight they had secured her so effectually, by barricading the place, as to prevent her escape. The horse, when first attacked, fought with great spirit, and if at liberty, would probably have beaten down his antagonist with his fore feet, but in plunging he embarrassed himself in the harness. The lioness attacked him in the front, and springing at his throat, fastened the talons of her fore feet on each side of his neck, close to the head, while the talons of her hind feet were forced into his chest. In this situation she hung, while the blood was seen flowing as if a vein had been opened by a fleam. He was a capital horse, the off-leader, the best in the set. The expressions of agony in his tears and moans were most pitious and affecting. A fresh horse having been procured, the mail drove on, after having been detained three quarters of an hour. As the mail drew up it stood exactly abreast of the caravan from which the lioness made the assault. The coachman at first proposed to alight and stab the lioness with a knife, but was prevented by the remonstrance of the guard; who observed, that he would expose himself to certain destruction, as the animal if attacked would naturally turn upon him and tear him to pieces. The prudence of the advice was clearly proved by the fate of the dog. It was the engagement between him and the lioness that afforded time for the keepers to rally. After she had disengaged herself from the horse, she did not seem to be in any immediate hurry to move; for, whether she had carried off with her, as prey, the dog she had killed, or from some other cause, she continued growling and howling in so loud a tone, as to be heard for nearly half a mile. All had called out loudly to the guard to despatch her with his blunderbuss, which he appeared disposed to do, but the owner cried out to him, "For God's sake do not kill her—she cost me 500l., and she will be as quiet as a limb if not irritated." This arrested his hand, and he did not fire. She was afterwards easily enticed by the keepers, and placed in her usual confinement.

The collection of animals in Ballard's menagerie is altogether highly interesting, but it seems impossible that the proprietor could exhibit them for "only a penny" in any other place than "Bartholomew Fair," where the people assemble in great multitudes, and the shows are thronged the whole day.

SHOW XVI.

"Exhibition of Real Wonders."

This announcement, designed to astonish, was inscribed over the show with the usual notice, "Only a Penny!"—the "Wonders of the Deep!" the "Prodigies of the Age!" and "the Learned Pig!" in large letters. The printed bill is a curiosity:—

To be Seen in a Commodious Pavilion in

this Place.

REAL WONDERS!

SEE AND BELIEVE.

Have you seen

THE BEAUTIFUL DOLPHIN,

The Performing Pig & the Mermaid?

If not, pray do! as the exhibition contains more variety than any other in England. Those ladies and gentlemen who may be pleased to honour it with a visit will be truly gratified.

TOBY,

The Swinish Philosopher, and Ladies' Fortune Teller.

That beautiful animal appears to be endowed with the natural sense of the human being. He is in colour the most beautiful of his race; in symmetry the most perfect; in temper the most docile; and far exceeds any thing yet seen for his intelligent performances. He is beyond all conception: he has a perfect knowledge of the alphabet, understands arithmetic, and will spell and cast accounts, tell the points of the globe, the dice-box, the hour by any person's watch, &c.

the Real Head of

MAHOWRA,

THE CANNIBAL CHIEF.

At the same time, the public will have an opportunity of seeing what was exhibited so long in London, under the title of

THE MERMAID:

The wonder of the deep! not a fac-simile

or copy, but the same curiosity.Admission Moderate.

* * * Open from Eleven in the Morning till

Nine in the Evening.The great "prodigies" of this show were the "performing pig," and the performing show-woman. She drew forth the learning of the "swinish philosopher" admirably. He told his letters, and "got into spelling" with his nose; and could do a sum of two figures "in addition." Then, at her desire, he routed out those of the company who were in love, or addicted to indulgence; and peremptorily grunted, that a "round, fat, oily"-faced personage at my elbow, "loved good eating, and a pipe, and a jug of good ale, better than the sight of the Living Skeleton!" The beautiful dolphin was a fish-skin stuffed. The mermaid was the last manufactured imposture of that name, exhibited for half-a-crown in Piccadilly, about a year before. The real head of Mahowra, the cannibal chief, was a skull that might have been some English clodpole's, with a dried skin over it, and bewigged; but it looked sufficiently terrific, when the lady show-woman put the candle in at the neck, and the flame illuminated the yellow integument over the holes where eyes, nose, and a tongue had been. There was enough for "a penny!"

SHOW XVII.

Another "Only a penny!" with pictures "large as life" on the show-cloths outside of the "living wonders within," and the following inscription:—

ALL ALIVE!

No False Paintings!

THE WILD INDIAN,

THE

GIANT BOY,

And the

DWARF FAMILY,

Never here before,

TO BE SEEN ALIVE!

Mr. Thomas Day was the reputed father of the dwarf family, and exhibited himself as small enough for a great wonder; as he was. He was also proprietor of the show; and said he was thirty-five years of age, and only thirty-five inches high. He fittingly descanted on the living personages in whom he had a vested interest. There was a boy six years old, only twenty-seven inches high. The Wild Indian was a civil-looking man of colour. The Giant Boy, William Wilkinson Whitehead, was fourteen years of age on the 26th of March last, stood five feet two inches high, measured five feet around the body, twenty-seven inches across the shoulders, twenty inches round the arm, twenty-four inches round the calf, thirty-one inches round the thigh, and weighed twenty-two stone. His father and mother were "travelling merchants" of Manchester; he was born at Glasgow during one of their journies, and was as fine a youth as I ever saw, handsomely formed, of fair complexion, and intelligent countenance, active in motion, and of sensible speech. He was lightly dressed in plaid to show his limbs, with a bonnet of the same. The artist with me sketched his appearance exactly as we saw him, and as the present engraving now represents him; it is a good likeness of his features, as well as of his form.

The Giant Boy.

SHOW XVIII."Holden's Glass Working and Blowing."

This was the last show on the east-side of Smithfield. It was limited to a single caravan; having seen exhibitions of the same kind, and the evening getting late, I declined entering, though "Only a penny!"

SHOW XIX.

This was the first show on the south-side of Smithfield. It stood, therefore, with its side towards Cloth-fair, and the back towards the corner of Duke-street. The admission was "Only a penny!" and the paintings flared on the show-cloths with this inscription, "They're all Alive Inside! Be assured They're All Alive!—The Yorkshire Giantess.—Waterloo Giant.—Indian Chief.—Only a Penny!"

An overgrown girl was the Yorkshire Giantess. A large man with a tail, and his hair frizzed and powdered, aided by a sort of uniform coat and a plaid rocquelaire, made the Waterloo Giant. The abdication of such an Indian Chief as this, in favour of Bartholomew Fair, was probably forced upon him by his tribe.

SHOW XX.

The "Greatest of all Wonders! — Giantess and Two Dwarfs. — Only a Penny!" They were painted on the show-cloths quite as little, and quite as large, as life. The dwarfs inside were dwarfish, and the "Somerset girl, taller than any man in England," (for so said the show-cloth,) arose from a chair, wherein she was seated, to the height of six feet nine inches and three quarters, with, "ladies and gentlemen, your most obedient." She was good looking and affable, and obliged the "ladies and gentlemen" by taking off her tight-fitting slipper and handing it round. It was of such dimension, that the largest man present could have put his booted foot into it. She said that her name was Elizabeth Stock, and that she was only sixteen years old.

SHOW XXI.

CHAPPELL—PIKE.

This was a very large show, without any show-cloths or other announcement outside to intimate the performances, except a clown and several male and female performers, who strutted the platform in their exhibiting dresses, and in dignified silence; but the clown grimaced, and, assisted by others, bawled "Only a penny," till the place filled, and then the show commenced. There was slack-rope dancing, tumbling, and other representations as at Ball's theatre, but better executed.

SHOW XXII.

WOMBWELL.

The back of this man's menagerie abutted on the side of the last show, and ran the remaining length of the north-side of Smithfield, with the front looking towards Giltspur-street; at that entrance into the Fair it was the first show. This front was entirely covered by painted show-cloths representing the animals, with the proprietor's name in immense letters above, and the words "The Conquering Lion" very conspicuous. There were other show-cloths along the whole length of the side, surmounted by this inscription, stretching out in one line of large capital letters, "NERO AND WALLACE; THE SAME LIONS THAT FOUGHT AT WARWICK." One of the front show-cloths represented one of the fights; a lion stood up with a dog in his mouth, crunched between his grinders; the blood ran from his jaws; his left leg stood upon another dog squelched by his weight. A third dog was in the act of flying at him ferociously, and one, wounded and bleeding, was fearfully retreating. There were seven other show-cloths on this front, with the words "NERO AND WALLACE" between them. One of these show-cloths, whereon the monarch of the forest was painted, was inscribed, "Nero, the Great Lion, from Caffraria!"

The printed bill described the whole collection to be in "fine order." Six-pence was the entrance money demanded, which having paid, I entered the show early in the afternoon, although it is now mentioned last, in conformity to its position in the Fair. I had experienced some inconvenience, and witnessed some irregularities incident to a mixed multitude filling so large a space as Smithfield; yet no disorder without, was equal to the disorder within Wombwell's. There was no passage at the end, through which persons might make their way out: perhaps this was part of the proprietor's policy, for he might imagine that the universal disgust that prevailed in London, while he was manifesting his brutal cupidity at Warwick, had not subsided; and that it was necessary his show-place here should appear to fill well on the first day of the Fair, lest a report of general indifference to it, should induce many persons to forego the gratification of their curiosity, in accommodation to the natural and right feeling that induced a determination not to enter the exhibition of a man who had freely submitted his animals to be tortured. Be that as it may, his show, when I saw it, was a shameful scene. There was no person in attendance to exhibit or point out the animals[.] They were arranged on one side only, and I made my way with difficulty towards the end, where a loutish fellow with a broomstick, stood against one of the dens, from whom I could only obtain this information, that it was not his business to show the beasts, and that the showman would begin at a proper time. I patiently waited, expecting some announcement of this person's arrival; but no intimation of it was given; at length I discovered over the heads of the unconscious crowd around, that the showman, who was evidently under the influence of drink, had already made his way one third along the show. With great difficulty I forced myself through the sweltering press somewhat nearer to him, and managed to get opposite Nero's den, which he had by that time reached and clambered into, and into which he invited any of the spectators who chose to pay him sixpence each, as many of them did, for the sake of saying that they had been in the den with the noble animal, that Wombwell, his master, had exposed to be baited by bull-dogs. The man was as greedy of gain as his master, and therefore without the least regard to those who wished for general information concerning the different animals, he maintained his post as long as there was a prospect of getting the sixpences. Pressure and heat were now so excessive, that I was compelled to struggle my way, as many others did, towards the door at the front end, for the sake of getting into the air. Unquestionably I should not have entered Wombwell's, but for the purpose of describing his exhibition in common with others. As I had failed in obtaining the information I sought, and could not get a printed bill when I entered, I re-ascended to endeavour for one again; here I saw Wombwell, to whom I civilly stated the great inconvenience within, which a little alteration would have obviated; he affected to know nothing about it, refused to be convinced, and exhibited himself, to my judgment of him, with an understanding and feelings perverted by avarice. He is undersized in mind as well as form, "a weazen, sharp-faced man," with a skin reddened by more than natural spirits, and he speaks in a voice and language that accord with his feelings and propensities. His bill mentions, "A remarkably fine tigress in the same den with a noble British lion!!" I looked for this companionship in his menagerie, without being able to discover it.

Here ends my account of the various shows in the Fair. In passing the stalls, the following bill was slipped into my hand, by a man stationed to give them away.

SERIOUS NOTICE,

IN PERFECT CONFIDENCE.

The following extraordinary comic performances at

Sadler's Wells,

Can only be given during the present week; the proprietors, therefore, most respectfully inform that fascinating sex, so properly distinguished by the appropriate appellation of

THE FAIR!

And all those well inclined gentlemen who are happy enough to protect them, that the amusements will consist of a romantic tale, of mysterious horror and broad grin, never acted, called the

ENCHANTED

GIRDLES;

OR,

WINKI THE WITCH,

And the Ladies of Samarcand.

A most whimsical burletta, which sends

people home perfectly exhausted from

uninterrupted risibility, calledTHE LAWYER, THE JEW,

AND

THE YORKSHIREMAN.

With, by request of 75 distinguished families, and a party of 5, that never-to-be-sufficiently-praised pantomime, called

Magic in Two Colours;

OR,

FAIRY BLUE & FAIRY RED:

Or, Harlequin and the Marble Rock.

It would be perfectly superfluous for any man in his sense to attempt any thing more than the mere announcement in recommendation of the above unparalleled representations, so attractive in themselves as to threaten a complete monopoly of the qualities of the magnet; and though the proprietors were to talk nonsense for an hour, they could not assert a more important truth than that they possess

The only Wells from which you may draw

WINE,

THREE SHILLINGS AND SIXPENCE

A full Quart.Those whose important avocations prevent their coming at the commencement,

will be admitted forHALF-PRICE, AT HALF-PAST EIGHT.

Ladies and gentlemen who are not judges of superior entertainments announced, are respectfully requested to bring as many as possible with them who are.

N. B. A full Moon during the Week.

This bill is here inserted as a curious specimen of the method adopted to draw an audience to the superior entertainments of a pleasant little summer theatre, which, to its credit, discourages the nuisances that annoy every parent who takes his family to the boxes at the other theatres.

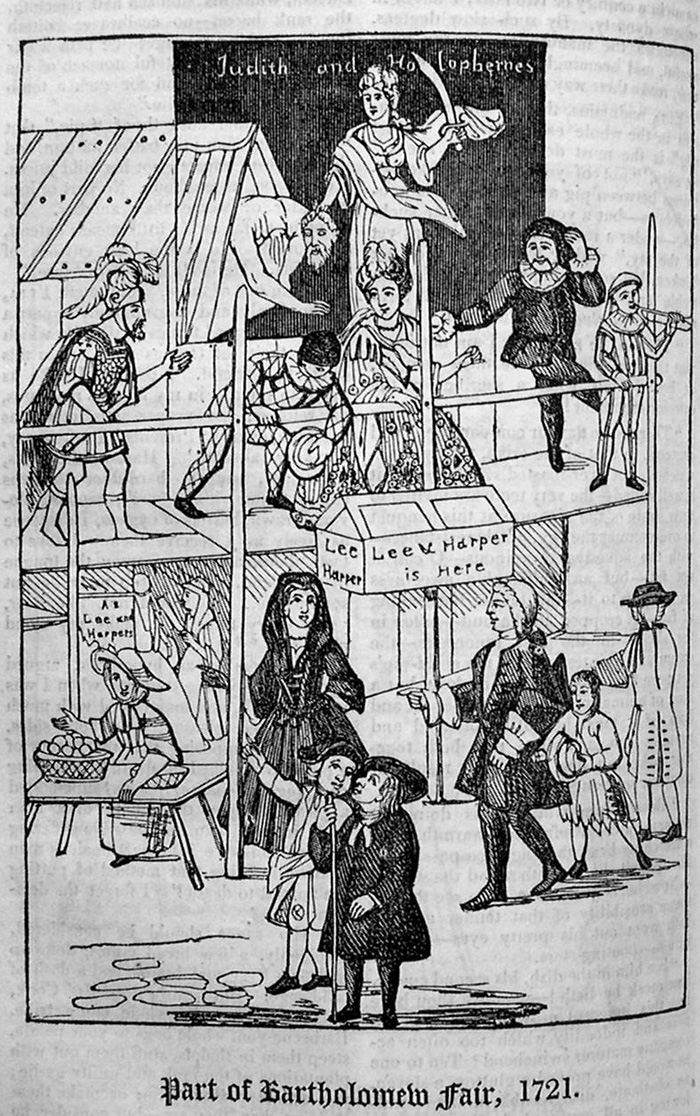

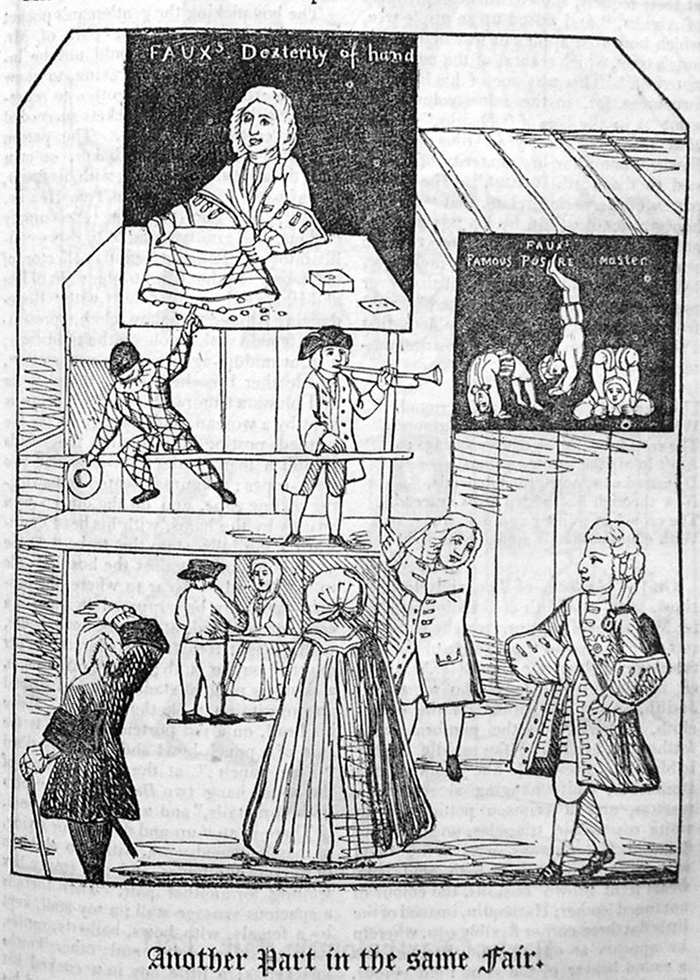

Before mentioning other particulars concerning the Fair here described, I present a lively representation of it in former times.

Bartholomew Fair in 1614.

"O, rare Ben Jonson!" To him we are indebted for the only picture of Smithfield at "Barthol'me'-tide" in his time.

In his play of "Bartholomew Fair," we have John Littlewit, a proctor "o' the Archdeacon's-court," and "one of the pretty wits o' Paul's" persuading his wife, Win-the-fight, to go to the Fair. He says "I have an affair i' the Fair, Win, a puppet-play of mine own making.—I writ for the motion-man." She tells him that her mother, dame Purecraft, will never consent; whereupon he says, "Tut, we'll have a device, a dainty one: long to eat of a pig, Sweet Win, i' the Fair; do you see? i' the heart o' the Fair; not at Pye-corner. Your mother will do any thing to satisfie your longing." Upon this hint, Win prevails with her mother, to consult Zeal-of-the-land Busy, a Banbury man "of a most lunatick conscience and spleen;" who is of opinion that pig "is a meat, and a meat that is nourishing, and may be eaten; very exceeding well eaten; but in the Fair, and as a Bartholomew pig, it cannot be eaten; for the very calling it a Bartholomew pig, and to eat it so, is a spice of idolatry." After much deliberation, however, he allows that so that the offence "be shadowed, as it were, it may be eaten, and in the Fair, I take it—in a booth." He says "there may be a good use made of it too, now I think on't, by the public eating of swine's flesh, to profess our hate and loathing of Judaism;" and therefore he goes with them.

In the Fair a quarrel falls out between Lanthorn Leatherhead, "a hobby-horse seller," and Joan Trash, "a gingerbread woman."

"Leatherhead. Do you hear, sister Trash, lady o' the basket? sit farther with your gingerbread progeny there, and hinder not the prospect of my shop, or I'll ha' it proclaim'd i' the Fair, what stuff they are made on.

"Trash. Why, what stuff are they made on, brother Leatherhead? nothing but what's wholesome, I assure you.

"Leatherhead. Yes; stale bread, rotten eggs, musty ginger, and dead honey, you know.

"Trash. Thou too proud pedlar, do thy worst: I defy thee, I, and thy stable of hobby-horses. I pay for my ground, as well as thou dost, and thou wrongs't me, for all thou art parcel-poet, and an ingineer. I'll find a friend shall right me, and make a ballad of thee, and thy cattle all over. Are you puft up with the pride of your wares? your arsedine?

"Leatherhead. Go too, old Joan, I'll talk with you anon; and take you down too—I'll ha' you i' the Pie-pouldres."

They drop their abuse and pursue their vocation. Leatherhead calls, "What do you lack? what is't you buy? what do you lack? rattles, drums, halberts, horses, babies o' the best? fiddles o' the finest?" Trash cries, "Buy my gingerbread, gilt gingerbread!" A "costard-monger" bawls out, "buy any pears, pears! fine, very fine pears!" Nightingale, another character, sings,

"Hey, now the Fair's a filling

O, for a tune to startle

The birds o' the booths, here billing,

Yearly with old Saint Barthle!

The drunkards they are wading,

The punks and chapmen trading,

Who 'ld see the Fair without his lading?

Buy my ballads! new ballads!"

Ursula, "a pig-woman," laments her vocation: — "Who would wear out their youth and prime thus, in roasting of pigs, that had any cooler occupation? I am all fire and fat; I shall e'en melt away—a poor vex'd thing I am; I feel myselft dropping already as fast as I can: two stone of sewet a-day is my proportion: I can but hold life and soul together." Then she soliloquizes concerning Mooncalf, her tapster, and her other vocations: "How can I hope that ever he'll discharge his place of trust, tapster, a man of reckoning under me, that remembers nothing I say to him? but look to't, sirrah, you were best; threepence a pipe-full I will ha' made of all my whole half pound of tobacco, and a quarter of a pound of colts-foot, mixt with it to, to eech it out. Then six-and-twenty shillings a barrel I will advance o' my beer, and fifty shillings a hundred o' my bottle ale; I ha' told you the ways how to raise it. (a knock.) Look who's there, sirrah! five shillings a pig is my price at least; if it be a sow-pig sixpence more." Jordan Knockhum, "a horse-courser and a ranger of Turnbull," calls for "a fresh bottle of ale, and a pipe of tobacco." Passengers enter, and Leatherhead says, "What do you lack, gentlemen? Maid, see a fine hobby-horse for your young master." A corn-cutter cries, "Ha' you any corns i' your feet and toes?" Then "a tinder-box man" calls, "Buy a mouse-trap, a mouse-trap, or a tormentor for a flea!" Trash cries, "Buy some ginger-bread!" Nightingale bawls, "Ballads, ballads, fine new ballads!" Leatherhead repeats, "What do you lack, gentlemen, what is't you lack? a fine horse? a lion? a bull? a bear? a dog? or a cat? an excellent fine Bartholomew bird? or an instrument? what is't you lack?" The pig-woman quarrels with her guests and falls foul on her tapster: "In, you rogue, and wipe the pigs, and mend the fire, that they fall not; or I'll both baste and wast you till your eyes drop out, like 'em." Knockhum says to the female passengers, "Gentlewomen, the weather's hot! whither walk you? Have a care o' your fine velvet caps, the Fair is dusty. Take a sweet delicate booth, with boughs, here, i' the way, and cool yourselves i' the shade; you and your friends. The best pig and bottle ale i' the Fair, sir, old Urs'la is cook; there, you may read; the pig's head speaks it." Knockhum adds, that she roasted her pigs "with fire o' juniper, and rosemary branches." Littlewit, the proctor, and his wife, Win-the-fight, with her mother, dame Purecroft, and Zeal-of-the-land enter. Busy Knockhum suggests to Ursula that they are customers of the right sort, "In, and set a couple o' pigs o' the board, and half a dozen of the bygist bottles afore 'em—two to a pig, away!" In another scene Leatherhead cries, "Fine purses, pouches, pincases, pipes; what is't you lack? a pair o' smiths to wake you i' the morning? or a fine whistling bird?" Bartholomew Cokes, a silly "esquire of Harrow," stops at Leatherhead's to purchase: "Those six horses, friend, I'll have; and the three Jews trumps; and a half a dozen o' birds; and that drum; and your smiths (I like that device o' your smiths,)—and four halberts; and, let me see, that fine painted great leady, and her three women for state, I'll have. A set of those violins I would buy too, for a delicate young noise I have i' the country, that are every one a size less than another, just like your fiddles." Trash invites him to buy her gingerbread, and he turns to her basket, whereupon Leatherhead says, "Is this well, Goody Joan, to interrupt my market in the midst, and call away my customers? can you answer this at the Pie-pouldres?" whereto Trash replies, "Why, if his master-ship have a mind to buy, I hope my ware lies as open as anothers; I may shew my ware as well as you yours." Nightingale begins to sing,

"My masters and friends, and good

people draw near."Cokes hears this, and says, "Ballads! hark, hark! pray thee, fellow, stay a little! What ballads hast thou? let me see, let me see myself—How dost thou call it? 'A Caveat against Cut-purses!' — a good jest, i' faith; I would fain see that demon, your cut-purse, you talk of." He then shows his purse boastingly, and inquires, "Ballad-man, do any cut-purses haunt hereabout? pray thee raise me one or two: begin and shew me one." Nightingale answers, "Sir, this is a spell against 'em, spick and span new: and 'tis made as 'twere in mine own person, and I sing it in mine own defence. But 'twill cost a penny alone if you buy it." Cokes replies, "No matter for the price; thou dost not know me I see, I am an odd Bartholmew." The ballad has "pictures," and Nightingale tells him, "It was intended, sir, as if a purse should chance to be cut in my presence, now; I may be blameless though; as by the sequel will more plainly appear." He adds, it is "to the tune of 'Paggington's Pound,' sir," and he finally sings—

A Caveat against Cut-purses.

My masters, and friends, and good people draw near,

And look to your purses, for that I do say;

And though little money, in them you do bear,

It cost more to get, than to lose in a day,

You oft' have been told,

Both the young and the old,

And bidden beware of the cut-purse so bold:

Then if you take heed not, free me from the curse,

Who both give you warning, for, and the cut-purse,

Youth, youth, thou hadst better been starved by thy nurse,

Than live to be hanged for cutting a purse.It hath been upbraided to men of my trade,

That oftentimes we are the cause of this crime:

Alack, and for pity, why should it be said?

As if they regarded or places, or time.

Examples have been

Of some that were seen

In Westminster-hall, yea, the pleaders between;

They why should the judges be free from this curse

More than my poor self, for cutting the purse?

Youth, youth, thou hadst better been starved by thy nurse,

Than live to be hanged for cutting a purse.At Worc'ter 'tis known well, and even i' the jail,

A knight of good worship did there shew his face,

Against the foul sinners in zeal for to rail,

And lost, ipso facto, his purse in the place,

Nay, once from the seat

Of judgment so great,

A judge there did lose a fair pouch of velvet;

O, Lord for thy mercy, how wicked, or worse,

Are those that so venture their necks for a purse.

Youth, youth, thou hadst better been starved by thy nurse,

Than live to be hanged for stealing a purse.At plays, and at sermons, and at the sessions,

'Tis daily their practice such booty to make;

Yea, under the gallows, at executions,

They stick not the stare-abouts' purses to take.

Nay, one without grace,

At a better place,

At court, and in Christmas, before the king's face.

Alack! then, for pity, must I bear the curse,

That only belongs to the cunning cut-purse.

Youth, youth, thou hadst better been starved by thy nurse,

Than live to be hanged for stealing a purse.But O, you vile nation of cut-purses all,

Relent, and repent, and amend, and be sound,

And know that you ought not by honest men's fall,

Advance your own fortunes to die above ground.

And though you go gay

In silks as you may,

It is not the highway to heaven (as they say.)

Repent then, repent you, for better, for worse;

And kiss not the gallows for cutting a purse.

Youth, youth, thou hadst better been starved by thy nurse,

Than live to be hanged for cutting a purse.

While Nightingale sings this ballad, a fellow tickles Cokes's ear with a straw, to make him withdraw his hand from his pocket, and privately robs him of his purse, which, at the end of the song, he secretly conveys to the ballad-singer; who, notwithstanding his "Caveat against Cut-purses," is their principal confederate, and, in that quality, becomes the unsuspected depository of the plunder.

Littlewit tells his wife, Win, of the great hog, and of a bull with five legs, in the Fair. Zeal-of-the-land loudly declaims against the Fair, and against Trash's commodities:—"Hence with thy basket of popery, thy nest of images, and whole legend of ginger-work." He rails against "the prophane pipes, the tinkling timbrels;" and Adam Overdoo, a reforming justice of peace, one of "the court of Pie-powders," who wears a disguise for the better observation of disorder, gets into the stocks himself. Then "a western man, that's come to wrestle before my lord mayor anon," gets drunk, and is cried by "the clerk o' the market all the Fair over here, for my lord's service." Zeal-of-the-land Busy, too, is put with others into the stocks, and being asked, "what are you, sir?" he answers, "One that rejoiceth in his affliction, and sitteth here to prophesy the destruction of fairs and may-games, wakes and whitsun-ales, and doth sigh and groan for the reformation of these abuses." During a scuffle, the keepers of the stocks leave them open, and those who are confined withdraw their legs and walk away.

From a speech by Leatherhead, preparatory to exhibiting his "motion," or puppet-show, we become acquainted with the subjects, and the manner of the performance. He says, "Out with the sign of our invention, in the name of wit; all the fowl i' the Fair, I mean all the dirt in Smithfield, will be thrown at our banner to-day, if the matter does not please the people. O! the motions that I, Lanthorn Leatherhead, have given light to, i' my time, since my master, Pod, died! Jerusalem was a stately thing; and so was Nineveh and The City of Norwich, and Sodom and Gomorrah; with the Rising o' the Prentices, and pulling down the houses there upon Shrove-Tuesday; but the Gunpowder Plot, there was a get-penny! I have presented that to an eighteen or twenty pence audience nine times in an afternoon. Look to your gathering there, good master Filcher—and when there come any gentlefolks take twopence a-piece." He has a bill of his motion which reads thus: "The Ancient Modern History of Hero and Leander, otherwise called, the Touchstone of True Love, with as true a Trial of Friendship between Damon and Pythias, two faithful Friends o' the Bank-side." This was the motion written by Littlewit. Cokes arrives, and inquires, "What do we pay for coming in, fellow?" Filcher answers, "Twopence, sir."

"Cokes. What manner of matter is this, Mr. Littlewit? What kind of actors ha' you? are they good actors?

"Littlewit. Pretty youths, sir, all children both old and young, here's the master of 'em, Master Lantern, that gives light to the business.

"Cokes. In good time, sir, I would fain see 'em; I would be glad to drink with the young company; which is the tiring-house?

"Leatherhead. Troth, sir, our tiring-house is somewhat little; we are but beginners yet, pray pardon us; you cannot go upright in't.

"Cokes. No? not now my hat is off? what would you have done with me, if you had had me feather and all, as I was once to-day? Ha' you none of your pretty impudent boys now, to bring stools, fill tobacco, fetch ale, and beg money, as they have at other houses? let me see some o' your actors.

"Littlewit. Shew him 'em, shew him 'em. Master Lantern; this is a gentleman that is a favourer of the quality.

[Leatherhead brings the puppets out in a basket.]

"Cokes. What! do they live in baskets?

"Leatherhead. They do lie in a basket, sir: they are o' the small players.

"Cokes. These be players minor indeed. Do you call these play;rs? [sic]