June 24.

Nativity of St. John the Baptist. The Martyrs of Rome under Nero, A. D. 64. St. Bartholomew.

Midsummer-day.

Nativity of St. John the Baptist.

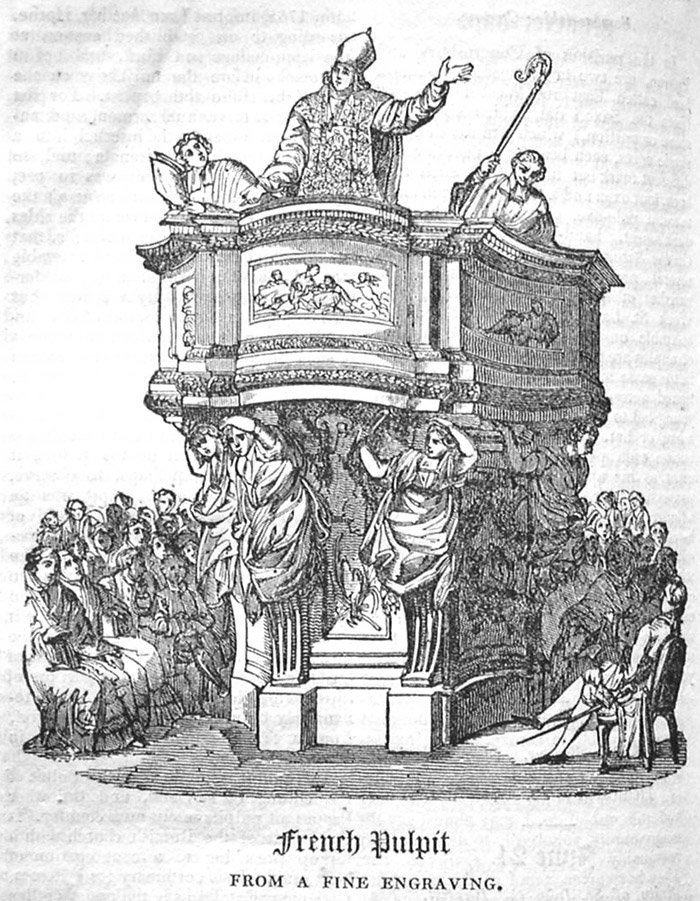

At Oxford on this day there was lately a remarkable custom, mentioned by the Rev. W. Jones of Nayland, in his "Life of Bishop Horne," affixed to the bishop's works. He says, "a letter of July the 25th, 1755, informed me that Mr. Horne, according to an established custom at Magdalen-college in Oxford, had begun to preach before the university on the day of St. John the baptist. For the preaching of this annual sermon, a permanent pulpit of stone is insered into a corner of the first quadrangle; and, so long as the stone pulpit was in use, (of which I have been a witness,) the quadrangle was furnished round the sides with a large fence of green boughs, that the preaching might more nearly resemble that of John the baptist in the wilderness; and a pleasant sight it was: but for many years the custom has been discontinued, and the assembly have thought it safer to take shelter under the roof of the chapel."

Pulpits.

Without descanting at this time on the manifold construction of the pulpit, it may be allowable, perhaps, to observe, that the ambo, or first pulipt, was an elevation consisting of two flights of stairs; on the higher was read the gospel, on the lower the epistle. The pulpit of the present day is that fixture in the church, or place of worship, occupied by the minister while he delivers his sermon. Thus much is observed for the present, in consequence of the mention of the Oxford pulpit; and for the purpose of introducing the representation of a remarkably beautiful structure of this kind, from a fine engraving by Fessard in 1710.

This pulpit is larger than the pulpit of the church of England, and the other Protestant pulpits in our own country. It is a pulpit of the Romish church with a bishop preaching to a congregation of high rank. It is customary for a Roman Catholic prelate to have the ensigns of his prelacy displayed in the pulpit, and hence they are so exhibited in Fessard's print. This, however, is by no means so large as other pulpits in Romish churches, which are of increased magnitude for the purpose of congregating the clergy, when their occupations at the altar have ceased, before the eye of the congregation; and hence it is common for many of them to sit robed, by the side of the preacher, during the sermon.

French Pulpit

FROM A FINE ENGRAVING.

An English lady visiting France, who had been mightily impressed by the rites of the Roman Catholic religion, revived there since the restoration of the Bourbons, was induced to attend the Protestant worship, at the chapel of the British ambassador. She says "the splendour of the Romish service, the superb dresses, the chanting, accompanied by beautiful music, the lights, and the other ceremonies, completely overpowered my mind; at last on the Sunday before I left Paris I went to our ambassador's chapel, just to say that I had been. There was none of the pomp I had been so lately delighted with; the prevailing character of the worship was simplicity; the minister who delivered the sermon was only sufficiently elevated to be seen by the auditors; he preached to a silent and attentive congregation, whose senses had not been previously affected; his discourse was earnest, persuasive, and convincing. I began to perceive the difference between appeals to the feelings and to the understanding, and I came home a better Protestant and I hope a better Christian than when I left England."

Quarter-day.

For the Every-Day Book.

This is quarter-day!—what a variety of thought and feeling it calls up in the minds of thousands in this great metropolis. How many changes of abode, voluntary and involuntary, for the better and for the worse, are now destined to take place! There is the charm of novelty at least; and when the mind is disposed to be pleased, as it is when the will leads, it inclines to extract gratification from the anticipation of advantages, rather than to be disturbed by any latent doubts which time may or may not realize.

Perhaps the removal is to a house of decidedly superior class to the present; and if this stop is the consequence of augmented resources, it is the first indication to the world of the happy circumstance. Here, then, is a an additional ground of pleasure, not very heroic indeed, but perfectly natural. Experience may have shown us that mere progression in life is not always connected with progression in happiness; and therefore, though we may smile at the simplicity which connects them in idea, yet our recollection of times past, when we ourselves indulged the delusion, precludes us from expressing feelings that we have acquired by experience. The pleasure, if from a shallow source, is at least a present benefit, and a sort of counterpoise to vexations from imaginary causes. It does not seem agreeable to contemplate retrogression; to behold a family descending from their wonted sphere, and becoming the inmates of a humbler dwelling; yet, they who have had the resolution, I may almost say the magnanimity, voluntarily to descend, may reasonably be expected again to rise. They have given proof of the possession of one quality indispensible in such an attempt — that mental decision, by which they have achieved a task, difficult, painful, and to many, impracticable. They have shown, too, their ability to form a correct estimate of the value of the world's opinion, so far as it is influenced by external appearances, and boldly disregarding its terrors, have wisely resolved to let go that which could not be much longer held. By this determination, besides rescuing themselves from a variety of perpetually recurring embarrassments and annoyances, they have suppressed half the sneers which the malicious had in store for them had their decline reached its expected crisis, while they have secured the approbation and kind wishes of all the good and considerate. The consciousness of this consoles them for what is past, contents them with the present, and animates their hopes for the future.

Now, let us shift the scene a little, and look at quarter-day under another aspect. On this day some may quit, some may remain; all must pay—that can! Alas, that there should be some unable! I pass over the rich, whether landlord or tenant; the effects of quarter-day to them are sufficiently obvious: they feel little or no sensation on its approach or arrival, and when it is over, they feel not alteration their accustomed necessaries and luxuries. Not so with the poor man; I mean the man who, in whatever station, feels his growing inability to meet the demands periodically and continually making on him. What a day quarter-day is to him! He sees its approach from a distance, tries to be prepared, counts his expected means of being so, finds them short of even his not very sanguine expectations, counts again, but can make no more of them; and while day after day elapses, sees his little stock diminishing. What shall he do? He perhaps knows his landlord to be inexorable; how then shall he satisfy him? Shall he borrow? Alas, of whom? Where dwell the practicers of this precept—"From him that would borrow of thee turn thous not away?" Most of the professors of the religion which enjoins this precept, construe it differently. What shall he do? something must be soon decided on. He sits down to consider. He looks about his neatly-furnished house or apartments, to see what out of his humble possessions, he can convert into money. The faithful wife of his bosom becomes of his council. There is nothing they have, which they did not purchase for some particular, and as they then thought, necessary purpose; how, then, can they spare any thing? they ruminate; they repeat the names of the various articles, they fix on nothing—there is nothing they can part with. They are about so to decide; but their recollection that external resources are now all dried up, obliges them to resume their task, and resolutely determine to do without something, however painful may be the sacrifice. Could we hear the reasons which persons thus situated assign, why this or that article should by no means be parted with, we should be enabled, in some degree, to appreciate their conflicts, and the heart-aches which precede and accompany them. In such inventories much jewellery, diamond rings, or valuable trinkets, are not to be expected. The few that there may be, are probably tokens of affection, either from some deceased relative or dear friend; or not less likely from the husband to the wife, given at their union—"when life and hope were new"—when their minds were so full of felicity, that no room was left for doubts as to its permanence; when every future scene appeared to their glowing imaginations dressed in beauty; when every scheme projected, appeared already crowned with success; when the possibility of contingencies frustating [sic] judicious endeavours, either did not present itself to the mind, or presenting itself, was dismissed as an unwelcome guest, "not having on the wedding garment." At such a time were those tokens presented, and they are now produced. They serve to recal moments of bliss unalloyed by cares, since become familiar. They were once valued as pledges of affection, and now, when that affection endures in full force and tenderness, they wish that those pledges had no other value than affection confers on them, that so there might be no temptation to sacrifice them to a cruel necessity. Let us, however, suppose some of them selected for disposal, and the money raised to meet the portentous day. Our troubled fellow-creatures breathe again, all dread is for the present banished; joy, temporary, but oh! how sweet after such bitterness, is diffused through their hearts, and gratitude to Providence for tranquility, even by such means restored, is a pervading feeling. It is, perhaps, prudent at this juncture to leave them, rather than follow on to the end of the next quarter. It may be that, by superior prudence or some unexpected supply, a repetition of the same evil, or the occurrence of a greater is avoided; yet, we all know that evils of the kind in question, are too frequently followed by worse. If a family, owing to the operation of some common cause, such as a rise in the price of provisions, or a partial diminution of income from the depression of business, become embarrassed and with difficulty enabled to pay their rent; the addition of a fit of sickness, the unexpected failure of a debtor, or any other contingency of the sort, (assistance from without not being afforded,) prevents them altogether. The case is then desperate. The power which the law thus permits a landlord to exercise, is one of feaful magnitude, and is certainly admirably calculated to discover the stuff he is made of. Yet, strange as it seems, this power is often enforced in all its rigour, and the merciless enforcers lose not, apparently, a jot of reputation, nor forfeit the esteem of their intimates: so much does familiarity with an oppressive action deaden the perception of its real nature, and so apt are we to forget that owing to the imperfection of human institutions, an action may be legal and cruel at the same time! The common phrase, "So and so have had their goods seized for rent," often uttered with indifference and heard without emotion, is a phrase pregnant with meaning of the direst import. It means that they—wife, children, and all—who last night sat in a decent room, surrounded by their own furniture, have now not a chair of their own to sit on; that they, who last night could retire to a comfortable bed, after the fatigues and anxieties of the day, have tonight not a bed to lie on—or none but what the doubtful ability or humanity of strangers or relations may supply: it means that sighs and tears are produced, where once smiles and tranquillity existed; or, perhaps, that long cherished hopes of surmounting difficulties, have by one blow been utterly destroyed,—that the stock of expedients long becoming threadbare, is at last quite worn out, and all past efforts rendered of no avail, though some for a time seemed likely to be available. It means that the hollowness of professed friends has been made manifest; that the busy tongue of detraction has found employment; that malice is rejoicing; envy is at a feast; and that the viands are the afflictions of the desolate. Landlord! ponder on these consequences ere you distrain for rent, and let your heart, rather than the law, be the guide of your conduct. The additional money you may receive by distraining may, indeed, add something to the luxuries of your table, but it can hardly fail to diminish your relish. You may, perhaps, by adopting the harsh proceeding, add down to your pillow, but trust not that your sleep will be tranquil or your dreams pleasant. Above all remember the benediction—"Blessed are the merciful for they shall obtain mercy;" and inspired with the sentiment, and reflecting on the fluctuations which are every day occurring, the poor and humble raised, and the wealthy and apparently secure brought down, you will need no other incitement to fulfil the golden rule of your religion—"Do unto others as ye would they should do unto you."

SIGMA.

Concerning the Feast of St. John the Baptist, an author, to whom we are obliged for recollections of preceding customs, gives us information that should be carefully perused in the old versified version:—

Then doth the joyfull feast of John

the Baptist take his turne,

When bonfiers great, with loftie flame,

in every towne doe burne;

And yong men round about with maides,

doe daunce in every streete,

With garlands wrought of Motherwort,

or else with Vervain sweete,

And many other flowres faire,

with Violets in their handes,

Whereas they all do fondly thinke,

that whosoever standes,

And thorow the flowres beholds the flame,

his eyes shall feel no paine.

When thus till night they daunced have,

they through the fire amaine,

With striving mindes doe runne, and all

their hearbes they cast therein,

And then with wordes devout and prayers

they solemnely begin,

Desiring God that all their ills

may there consumed bee;

Whereby they thinke through all that yeare

from agues to be free.

Some others get a rotten Wheele,

all worne and cast aside,

Which covered round about with strawe

and tow, they closely hide:

And caryed to some mountaines top,

being all with fire light,

They hurle it downe with violence,

when darke appears the night:

Resembling much the sunne, that from

the Heavens down should fal,

A strange and monstrous sight it seemes,

and fearefull to them all:

But they suppose their mischiefes all

are likewise throwne to hell,

And that from harmes and daungers now,

in safetie here they dwell.*[1]

A very ancient "Homily" relates other particulars and superstitions relating to the bonfires on this day:—

"In worshyp of Saint Johan the people waked at home, and made three maner of fyres: one was clene bones, and noo woode, and that is called a bone fyre; another is clene woode, and no bones, and that is called a wood fyre, for people to sit and wake thereby; the thirde is made of wode and bones, and it is callyd Saynt Johannys fyre. The first fyre, as a great clerke, Johan Belleth, telleth, he was in a certayne countrey, so in the countrey there was so soo greate hete, the which causid that dragons to go togyther in tokenynge, that Johan dyed in brennygne love and charyte to God and man, and they that dye in charyte shall have part of all good prayers, and they that do not, shall never be saved. Then as these dragons flewe in th' ayre they shed down to that water froth of ther kynde, and so envenymed the waters, and caused moche people for to take theyr deth thereby, and many dyverse sykenesse. Wyse clerkes knoweth well that dragons hate nothyng more than the stenche of brennynge bones, and therefore they gaderyd as many as they mighte fynde, and brent them; and so with the stenche thereof they drove away the dragons, and so they were brought out of greete dysease. The seconde fyre was made of woode, for that wyll brenne lyght, and wyll be seen farre. For it is the chefe of fyre to be seen farre, and betokennynge that Saynt Johan was a lanterne of lyght to the people. Also the people made blases of fyre for that they shulde be seene farre, and specyally in the nyght, in token of St. Johan's having been seen from far in the spirit by Jeremiah. The third fyre of bones betokenneth Johan's martyrdome, for hys bones were brente." —Brand calls this "a pleasant absurdity;" the justice of the denomination can hardly be disputed.

Gebelin observes of these fires, that "they were kindled about midnight on the very moment of the summer solstice, by the greatest part as well of the ancient as of modern nations; and that this fire-lighting was a religious ceremony of the most remote antiquity, which was observed for the prosperity of states and people, and to dispel every kind of evil." He then proceeds to remark, that "the origin of this fire, which is still retained by so many nations, though enveloped in the mist of antiquity, is very simple: it was a feu de joie, kindled the very moment the year began; for the first of all years, and the most ancient that we know of, began at this month of June. Thence the very name of this month, junior, the youngest, which is renewed; while that of the preceding one is May, major, the ancient. Thus the one was the month of young people, while the other belonged to old men. These feux de joie were accompanied at the same time with vows and sacrifices for the propserity of the people and the fruits of the earth. They danced also round this fire; for what feast is there without a dance? and the most active leaped over it. Each on departing took away a fire-brand, great or small, and the remains were scattered to the wind, which, at the same time that it dispersed the ashes, was thought to expel every evil. When, after a long train of years, the year ceased to commence at this solstice, still the custom of making these fires at this time was continued by force of habit, and of those superstitious ideas that are annexed to it." So far remarks Gebelin concerning the universality of the practice.

Bourne, a chronicler of old customs, says, "that men and women were accustomed to gather together in the evening by the sea side, or in some certain houses, and there adorn a girl, after manner of a bride. Then they feasted and leaped after the manner of bacchanals, and danced and shouted as they were wont to do on their holidays; after this they poured into a narrow-necked vessel some of the sea water, and put also into it certain things belonging to each of them; then, as if the devil gifted the girl with the faculty of telling future things, they would inquire with a loud voice about the good or evil fortune that should attend them: upon this the girl would take out of the vessel the first thing that came to hand, and show it, and give it to the owner, who, upon receiving it, was so foolish as to imagine himself wiser as to the good or evil fortune that should attend him." "In Cornwall, particularly," says Borlase, "the people went with lighted torches, tarred and pitched at the end, and made their perambulations round their fires." They went "from village to village, carrying their torches before them, and this is certainly the remains of the Druid superstition."

And so in Ireland, according to sir Henry Piers, In Vallancey, "on the eves of St. John the baptist and St. Peter, they always have in every town a bonfire late in the evenings, and carry about bundles of reeds fast tied and fired; these being dry, will last long, and flame better than a torch, and be a pleasing divertive prospect to the distant beholder; a stranger would go near to imagine the whole country was on fire." Brand cites further, from "The Survey of the South of Ireland," that— "It is not strange that many Druid remains should still exist; but it is a little extraordinary that some of their customs should still be practised. They annually renew the sacrifices that used to be offered to Apollo, without knowing it. On Midsummer's eve, every eminence, near which is a habitation, blazes with bonfires; and round these they carry numerous torches, shouting and dancing, which affords a beautiful sight. Though historians had not given us the mythology of the pagan Irish, and though they had not told us expressly that they worshipped Beal, or Bealin, and that this Beal was the sun, and their chief god, it might, nevertheless, be investigated from this custom, which the lapse of so many centuries has not been able to wear away." Brand goes on to quote from the "Gentleman's Magazine," for February 1795, "The Irish have ever been worshippers of fire and of Baal, and are so to this day. This is owing to the Roman Catholics, who have artfully yielded to the superstitions of the natives, in order to gain and keep up an establishment, grafting christianity upon pagan rites. The chief festival in honour of the sun and fire is upon the 21st of June, when the sun arrives at the summer solstice, or rather begins its retrograde motion. I was so fortunate in the summer of 1782, as to have my curiosity gratified by a sight of this ceremony to a very great extent of country. At the house where I was entertained, it was told me that we should see at midnight the most singular sight in Ireland, which was the lighting of fires in honour of the sun. Accordingly, exactly at midnight, the fires began to appear: and taking the advantage of going up to the leads of the house, which had a widely extended view, I saw on a radius of thirty miles, all around, the fires burning on every eminence which the country afforded. I had a farther satisfaction in learning, from undoubted authority, that the people danced round the fires, and at the close went through these fires, and made their sons and daughters, together with their cattle, pass the fire; and the whole was conducted with religious solemnity."

Mr. Brand notices, that Mr. Douce has a curious French print, entitled "L'este le Feu de la St. Jean;" Mariette ex. In the centre is the fire made of wood piled up very regularly, and having a tree stuck in the midst of it. Young men and women are represented dancing round it hand in hand. Herbs are stuck in their hats and caps, and garlands of the same surround their waists, or are slung across their shoulders. A boy is represented carrying a large bough of a tree. Several spectators are looking on. The following lines are at the bottom:—

"Que de Feux brulans dans les airs!

Qu'ils font une douce harmonie!

Redoublons cette mélodie

Par nos dances, par nos concerts!"This "curious French print," furnished the engraving at page 825, or to speak more correctly, it was executed from one in the possession of the editor of the Every-Day Book.

To enliven the subject a little, we may recur to recent or existing usages at this period of the year. It may be stated then on the authority of Mr. Brand's collections, that the Eton scholars formerly had bonfires on St. John's day; that bonfires are still made on Midsummer eve in several villages of Gloucester, and also in the northern parts of England and in Wales; to which Mr. Brand adds, that there was one formerly at Whiteborough, a tumulus on St. Stephen's down near Launceston, in Cornwall. A large summer pole was fixed in the centre, round which the fuel was heaped up. It had a large bush on the top of it. Round this were parties of wrestlers contending for small prizes. An honest countryman, who had often been present at these merriments, informed Mr. Brand, that at one of them an evil spirit had appeared in the shape of a black dog, since which none could wrestle, even in jest, without receiving hurt: in consequence of which the wrestling was, in a great measure, laid aside. The rustics there believe that giants are buried in these tumuli, and nothing would tempt them to be so sacrilegious [sic] as to disturb their bones.

In Northumberland, it is customary on this day to dress out stools with a cushion of flowers. A layer of clay is placed on the stool, and therein is stuck, with great regularity, an arrangement of all kinds of flowers, so close as to forma beautiful cushion. These are exhibited at the doors of houses in the villages, and at the ends of streets and cross-lanes of larger towns, where the attendants beg money from passengers, to enable them to have an evening feast and dancing.*[2]

One of the "Cheap Repository Tracts," entitled, "Tawney Rachel, or the Fortune-Teller," said to have been written by Miss Hannah More, relates, among other superstitious practices of Sally Evans, that "she would never go to bed on Midsummer eve, without sticking up in her room the well-known plant called Midsummer Men, as the bending of the leaves to the right, or the left, would never fail to tell her whether her lover was true or false." The Midsummer Men were the orpyne plants, which Mr. Brand says is thus elegantly alluded to in the "Cottage Girl," a poem "written on Midsummer eve, 1786:"—

"The rustic maid invokes her swain;

And hails, to pensive damsels dear,

This eve, though direst of the year.

* * * * *

"Oft on the shrub she casts her eye,

That spoke her true-love's secret sigh;

Or else, alas! too plainly told

Her true-love's faithless heart was cold.'In the "Connoisseur," there is mention of divination on Midsummer eve. "I and my two sisters tried the dumb-cake together: you must know, two must make it, two bake it, two break it, and the third put it under each of their pillows, (but you must not speak a word all the time), and then you will dream of the man you are to have. This we did: and to be sure I did nothing all night but dream of Mr. Blossom. The same night, exactly at twelve o'clock, I sowed hemp-seed in our back-yard, and said to myself,---'Hemp-seed I sow, hemp-seed I hoe, and he that is my true-love come after me and mow.' Will you believe me? I looked back, and saw him behind me, as plain as eyes could see him. After that, I took a clean shift and wetted it, and turned it wrong-side out, and hung it to the fire upon the back of a chair; and very likely my sweetheart would have come and turned it right again, (for I heard his step) but I was frightened, and could not help speaking, which broke the charm. I likewise stuck up two Midsummer Men, one for myself and one for him. Now if his had died away, we should never have come together, but I assure you his blowed and turned to mine. Our maid Betty tells me, that if I go backwards, without speaking a word, into the garden upon Midsummer eve, and gather a rose, and keep it in a clean sheet of paper, without looking at it till Christmas-day, it will be as fresh as in June; and if I then stick it in my bosom, he that is to be my husband will come and take it out. My own sister Hetty, who died just before Christmas, stood in the church porch last Midsummer eve, to see all that were to die that year in our parish; and she saw her own apparition."

Gay, in one of his pastorals, says—

At eve last Midsummer no sleep I sought,

But to the field a bag of hemp-seed brought:

I scattered round the seed on every side,

And three times, in a trembling accent cried:—

"This hemp-seed with my virgin hand I sow,

Who shall my true love be, the crop shall mow."

I straight looked back, and, if my eyes speak truth,

With his keen scythe behind me came the youth.It is also a popular superstition that any unmarried woman fasting on Midsummer eve, and at midnight laying a clean cloth, with bread, cheese, and ale, and sitting down as if going to eat, the street-door being left open, the person whom she is afterwards to marry will come into the room and drink to her by bowing; and after filling the glass will leave it on the table, and, making another bow, retire.* [3]

So also the ignorant believe that any person fasting on Midsummer eve, and sitting in the church porch, will, at midnight, see the spirits of the presons of that parish who will die that year, come and knock at the church door, in the order and succession which they will die.

In the "Cottage Girl," before referred to, the gathering the rose on Midsummer eve and wearing it, is noticed as one of the modes by which a lass seeks to divine the sincerity of her suitor's vows:—

The moss-rose that, at fall of dew,

(Ere Eve its duskier curtain drew,)

Was freshly gather'd from its stem,

She values as the ruby gem;

And, guarded from the piercing air,

With all an anxious lover's care,

She bids it, for her shepherd's sake,

Await the new-year's frolic wake—

When, faded, in its alter'd hue

She reads—the rustic is untrue!

But, if it leaves the crimson paint,

Her sick'ning hopes no longer faint.

The rose upon her bosom worn,

She meets him at the peep of morn;

And lo! her lips with kisses prest,

He plucks it from her panting breast.

In "Time's Telescope," there is cited the following literal version of a beautiful ballad which has been sung for many centuries by the maidens, on the banks of the Guadalquivir in Spain, when they go forth to gather flowers on the morning of the festival of St. John the baptist:—

Spanish Ballad.

Come forth, come forth, my maidens, 'tis the day of good St. John,

It is the Baptist's morning that breaks the hills upon;

And let us all go forth together, while the blessed day is new,

To dress with flowers the snow-white wether, ere the sun has dried the dew.

Come forth, come forth, &c.Come forth, come forth, my maidens, the hedgerows all are green,

And the little birds are singing the opening leaves between;

And let us all go forth together, to gather trefoil by the stream,

Ere the face of Guadalquivir glows beneath the strengthening beam.

Come forth, come forth, &c.Come forth, come forth, my maidens, and slumber not away

The blessed, blessed morning of John the Baptist's day;

There's trefoil on the meadow, and lilies on the lee,

And hawthorn blossoms on the bush, which you must pluck with me.

Come forth, come forth, &c.Come forth, come forth, my maidens, the air is calm and cool,

And the violet blue far down ye'll view, reflected in the pool;

The violets and the roses, and the jasmines all together,

We'll bind in garlands on the brow of the strong and lovely wether.

Come forth, come forth, &c.Come forth, come forth, my maidens, we'll gather myrtle boughs,

And we all shall learn, from the dews of the fern, if our lads will keep their vows:

If the wether be still, as we dance on the hill, and the dew hangs sweet on the flowers,

Then we'll kiss off the dew, for our lovers are true, and the Baptist's blessing is ours.

Come forth, come forth, &c.Come forth, come forth, my maidens, 'tis the day of good St. John,

It is the Baptist's morning that breaks the hills upon;

And let us all go forth together, while the blessed day is new,

To dress with flowers the show-white wether, ere the sun has dried the dew.

Come forth, come forth, &c.

There are too many obvious traces of the fact to doubt its truth, that the making of bonfires, and the leaping through them, are vestiges of the ancient worship of the heathen god Bal; and therefore, it is, with propriety, that the editor of "Time's Telescope," adduces a recent occurrence from Hitchin's "History of Cornwall," as a probable remnant of pagan superstition in that county. He presumes that the vulgar notion which gave rise to it, was derived from the druidical sacrifices of beasts. "An ignorant old farmer in Cornwall, having met with some severe losses in his cattle, about the year 1800, was much afflicted with his misfortunes. To stop the growing evil, he applied to the farriers in his neighbourhood, but unfortunately he applied in vain. The malady still continuing, and all remedies failing, he thought it necessary to have recourse to some extraordinary measure. Accordingly, on consulting with some of his neighbours, equally ignorant with himself, and evidently not less barbarous, they recalled to their recollections a tale, which tradition had handed down from remote antiquity, that the calamity would not cease until he had actually burned alive the finest calf which he had upon his farm; but that, when this sacrifice was made, the murrian would afflict his cattle no more[.] The old farmer, influenced by this counsel, resolved immediately on reducing it to practice; that, by making the detestable experiment, he might secure an advantage, which the whisperers of tradition, and the advice of his neighbours, had conspired to assure him would follow. He accordingly called several of his friends together, on an appointed day, and having lighted a large fire, brought forth his best calf; and, without ceremony or remorse, pushed it into the flames. The innocent victim, on feeling the intolerable heat, endeavoured to escape; but this was in vain. The barbarians that surrounded the fire were armed with pitchforks, or pikes, as in Cornwall they are generally called; and, as the burning victim endeavoured to escape from death, with these instruments of cruelty the wretches pushed back the tortured animal into the flames. In this state, amidst the wounds of pitchforks, the shouts of unfeeling ignorance and cruelty, and the corrosion of flames, the dying victim poured out its expiring groan, and was consumed to ashes. It is scarcely possible to reflect on this instance of the superstitious barbarity, without tracing a kind of resemblance between it, and the ancient sacrifices of the Druids. This calf was sacrificed to fortune, or good luck, to avert impending calamity, and to ensure future prosperity, and was selcted by the farmer as the finest among his herd." Every intelligent native of Cornwall will percieve, that this extrct from the history of his county, is here made for the purpose of shaming the brutally ignorant, if it be possible, into humanity.

To conclude the present notices rather pleasantly, a little poem is subjoined, which shows that the superstition respecting the St. John's wort is not confined to England: it is a version of some lines transcribed from a German almanac:—

The St. John's Wort.

The young maid stole through the cottage door,

And blushed as she sought the plant of pow'r;—

"Thou silver glow-worm, O lend me thy light,

I must gather the mystic St. John's wort to-night,

The wonderful herb, whose leaf will decide

If the coming year shall make me a bride."

And the glow-worm came

With its silvery flame,

And sparkled and shone

Thro' the night of St. John,

And soon has the young maid her love-knot tied.With noiseless tread

To her chamber she sped,

Where the spectral moon her white beams shed:—

"Bloom here—bloom here, thou plant of pow'r,

To deck the young bride in her bridal hour!"

But it drooped its head that plant of power,

And died the mute death of the voiceless flower;

And a withered wreath on the ground it lay,

More meet for a burial than bridal day.And when a year was past away,

All pale on her bier the young maid lay

And the glow-worm came

with its silvery flame,

And sparkled and shone

Thro' the night of St. John,

And they closed the cold grave o'er the maid's cold clay.

It would be easy, and perhaps more agreeable to the editor than to his readers, to accumulate many other notices concerning the usages on this day; let it suffice, however, that we know enough to be assured, that knowledge is engendering good sense, and that the superstitions of our ancestors will in no long time have passed away for ever. Be it the business of their posterity to hasten their decay.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

St. John's Wort. Hypericum Pulchrum.

Nativity of St. John.