May 23.

St. Julia, 5th Cent. St. Desiderius, Bp. of Langres, 7th Cent. St. Desiderius, Bp. of Vienne, A.D. 612.

Whitsuntide.

Mr. Fosbroke remarks that this feast was celebrated in Spain with representations of the gift of the Holy Ghost, and of thunder from engines, which did much damage. Wafers, or cakes, preceded by water, oak-leaves, or burning torches, were thrown down from the church roof; small birds, with cakes tied to their legs, and pigeons were let loose; sometimes there were tame white ones tied with strings, or one of wood suspended. A long censer was also swung up and down. In an old Computus, anno 1509, of St. Patrick's, Dublin, we have ivs. viid. for making the angel (thurificantis) censing, and iis. iid. for cords of it—all on the feast of Pentecost. On the day before Whitsuntide, in some places, men and boys rolled themselves, after drinking, &c. in the mud in the streets. The Irish kept the feast with mild food, as among the Hebrews; and a breakfast composed of cake, bread, and a liquor made by hot water poured on wheaten bran. The Whitson Ales were derived from the Agapai, or love-feasts of the early Christians, and were so denominated from the churchwardens buying, and laying in from presents also, a large quantity of malt, which they brewed into beer, and sold out in the church or elsewhere. The profits, as well as those from sundry games, there being no poor rates, were given to the poor, for whom this was one mode of provision, according to the christian rule that all festivities should be rendered innocent by alms. Aubrey thus describes a Whitson Ale. "In every parish was a church-house, to which belonged spits, crocks, and other utensils for dressing provisions. Here the house-keepers met. The young people were there too, and had dancing, bowling, shooting at butts, &c. the ancients sitting gravely by, and looking on." It seems too that a tree was erected by the church door, where a banner was placed, and maidens stood gathering contributions. An arbour, called Robin Hood's Bower, was also put up in the church-yard. The modern Whitson Ale consists of a lord and lady of the ale, a steward, sword-bearer, purse-bearer, mace-bearer, train-bearer, or page, fool, and pipe and tabor man, with a company of young men and women, who dance in a barn.

ODE, WRITTEN ON WHIT-MONDAY.

Hark! how the merry bells ring jocund round,

And now they die upon the veering breeze;

Anon they thunder loud

Full on the musing ear.Wafted in varying cadence, by the shore

Of the still twinkling river, they bespeak

A day of jubilee,

An ancient holiday.And, lo! the rural revels are begun,

And gaily echoing to the laughing sky,

On the smooth-shaven green

Resounds the voice of Mirth—Alas! regardless of the tongue of Fate,

That tells them 'tis but as an hour since they,

Who now are in their graves,

Kept up the Whitsun dance;And that another hour, and they must fall

Like those who went before, and sleep as still

Beneath the silent sod,

A cold and cheerless sleep.Yet why whould thoughts like these intrude to scare

The vagrant Happiness, when she will deign

To smile upon us here,

A transient visitor?Mortals! be gladsome while ye have the power,

And laugh and seize the glittering lapse of joy;

In time the bell will toll

That warns ye to your graves.I to the woodland solitude will bend

My lonesome way—where Mirth's obstreperous shout

Shall not intrude to break

The meditative hour;There will I ponder on the state of man,

Joyless and sad of heart, and consecrate

This day of jubilee

To sad Reflection's shrine;And I will cast my fond eye far beyond

This world of care, to where the steeple loud

Shall rock above the sod,

Where I shall sleep in peace.H. K. White.

Whitsuntide at Greenwich.

I have had another holiday—a Whitsuntide holiday at Greenwich: it is true that I did not take a run down the hill, but I saw many do it who appeared to me happier and healthier for the exercise, and the fragrant breezes from the fine May trees of the park.

I began Whit-Monday by breakfasting on Blackheath hill. It was my good fortune to gain a sight of the beautiful grounds belonging to the noblest mansion on the heath, the residence of the princess Sophia of Gloucester. It is not a "show house," nor is her royal highness a woman of show. "She is a noble lady," said a worthy inhabitant of the neighbourhood, "she is always doing as much good as she can, and more, perhaps, than she ought; her heart is larger than her purse." I found myself in this retreat I scarcely know how, and imagined that a place like this might make good dispositions better, and intelligent minds wiser. Some of its scenes seemed, to my imagination, lovely as were the spots in "the blissful seats of Eden." Delightful green swards with majestic trees lead on to private walks; and gladdening shrubberies terminate in broad borders of fine flowers, or in sloping paths, whereon fairies might dance in silence by the sleeping moonlight, or to the chant of nightingales that come hither, to an amphitheatre of copses surrounding a "rose mount," as to their proper choir, and pour their melody, unheard by earthly beings,

————save by the ear

Of her alone who wanders here, or sits

Intrelissed and enchanted as the Fair

Fabled by him of yore in Comus' song,

Or rather like a saint in a fair shrine

Carved by Cellini's hand.It may not be good taste, in declaring the truth, to state "the whole truth," but it is a fact, that I descended from the heights of royalty to "Sot's hole." There, for "corporal refection," and from desire to see a place which derives its name from the great lord Chesterfield, I took a biscuit and a glass of ginger-beer. His lordship resided in the mansion I had just left, and his servants were acustomed to "use" this alehouse too frequently. On one occasion he said to his butler, "Fetch the fellows from that sot's hole:" from that time, though the house has another name and sign, it is better known by the name or sign of "Sot's hole." Ascending the rise to the nearest parkgate, I soon got to the observatory in the park. It was barely noon. The holiday folks had not yet arrived; the old pensioners, who ply there to ferry the eye up and down and across the river with their telescopes, were ready with their craft. Yielding to the importunity of one, to be freed from the invitations of the rest, I took my stand, and in less than ten minutes was conveyed to Barking church, Epping Forest, the men in chains, the London Docks, St. Paul's Cathedral, and Westminster Abbey. From the seat around the tree I watched the early comers; as each party arrived the pensioners hailed them with good success. In every instance, save one, the sight first demanded was the "men in chains:" these are the bodies of pirates, suspended on gibbets by the river side, to warn sailors against crimes on the high seas. An able-bodied sailor, with a new hat on his Saracen-looking head, carrying a handkerchief full of apples in his left hand, with a bottle neck sticking out of the neck of his jacket for a nosegay, dragged his female companion up the hill with all the might of his right arm and shoulder; and the moment he was at the top, assented to the proposal of a telescope-keeper for his "good lady" to have a view of the "men in chains." She wanted to "see something else first." "Don't be a fool," said Jack, "see them first; it's the best sight." No; not she: all Jack's arguments were unavailing. "Well! what is it you'd like better, you fool you?" "Why I wants to see our house in the court, with the flower-pots, and if I don't see that, I wont see nothing—what's the men in chains to that? Give us an apple." She took one out of the bundle, and beginning to eat it, gave instructions for the direction of the instrument towards Lime-house church, while Jack drew forth the bottle and refreshed himself. Long she looked, and squabbled, and almost gave up home of finding "our house;" but on a sudden she screamed out, "Here Jack! here it is, pots and all! and there's our bed-post; I left the window up o' purpose as I might see it!" Jack himself took an observation. "D'ye see it, Jack?" "Yes." "D'ye see the pots?" "Yes." "And the bed-post?" "Ay; and here Sal, here, here's the cat looking out o' the window." "Come away, let's look again;" and then she looked, and squalled "Lord! what a sweet place it is!" and then she assented to seeing the "men in chains," giving Jack the first look, and they looked "all down the river," and saw "Tom's ship," and wished Tom was with them. The breakings forth of nature and kind-heartedness, and especially the love of "home, sweet home," in Jack's "good lady," drew forth Jack's delight, and he kissed her till the apples rolled out of the bundle, and then he pulled her down the hill. From the moment they came up they looked at nobody, nor saw any thing but themselves, and what they paid for looking at through the telescope. They were themselves a sight: and though the woman was far from

whatever fair

High fancy forms or lavish hearts could wish,yet she was all that to Jack; and all that she seemed to love or care for, were "our house," and the "flower-pots," and the "bed-post," and "Jack."

At the entrances in all the streets of Greenwich, notices from the magistrates were posted, that they were determined to put down the fair; and accordingly not a show was to be seen in the place wherein the fair had of late been held. Booths were fitting up for dancing and refreshment at night, but neither Richardson's nor any other itinerant company of performers, was there. There were gingerbread stall, but no learned pig, no dwarf, no giant, no fire-eater, no exhibition of any kind. There was a large round-about of wooden horses for boys, and a few swings, none of them half filled. The landlord of "the Struggler" could not struggle his stand into notice. In vain he chalked up "Hagger's entire, two-pence a bottle:" this was ginger-beer; if it was not brisker than the demand for it, it was made "poor indeed;" he had little aid, but unsold "Lemmun aid, one penny a glass." Yet the public-houses in Greenwich were filling fast, and the fiddles squeaked from several first-floor windows. It was now nearly two o'clock, and the stage-coaches from London, thoroughly filled inside and out, drove rapidly in: these, and the flocking down of foot passengers, gave sign of great visitation. One object I cannot pass by, for it forcibly contrasted in my mind with the joyous disposition of the day. It was a poor blackbird in a cage, from the first-floor window of a house in Melville-place. The cage was high and square; its bars were of a dark brown bamboo; the top and bottom were of the same dolorous colour; between the bars were strong iron wires; the bird himself sat dull and mute; I passed the house several times; not a single note did he give forth. A few hours before I had heard his fellows in the thickets whistling in full throat; and here was he, in endless thrall, without a bit of green to cheer him, or even the decent jailery of a light wicker cage. I looked at him, and though of the Lollards at Lambeth, of Thomas Delaune in Newgate, of Prynne in the Gatehouse, and Laud in the Tower: —all these were offenders; yet wherein had this poor bird offended that he should be like them, and be forced to keep Whitsuntide in prison? I wished him a holiday, and would have given him one to the end of his life, had I known how.

After dining and taking tea at the "Yorkshire Grey," I returned to the park, through the Greenwich gate, near the hospital. The scene here was very lively. Great numbers were seated on the grass, some refreshing themselves, others were lookers at the large company of walkers. Surrounded by a goodly number was a man who stood to exhibit the wonders of a single-folded sheet of writing paper to the sight of all except himself; he was blind. By a motion of his hand he changed it into various forms. "Here," said he, "is a garden-chair for your seat—this is a flight of stairs to your chamber—here is a flower-stand for your mantle-piece;" and so he went on; presenting, in rapid succession, the well-shaped representation of more than thirty forms of different utensils or conveniences: at the conclusion, he was well rewarded for his ingenuity. Further on was a larger group; from the centre whereof came forth sounds unlike those heard by him who wrote—

"Orpheus play'd so well, he moved old Nick,

But thou mov'st nothing but thy fiddle-stick."This player so "imitated Orpheus," that he moved the very bowels, uneasiness seemed to seize on all who heard his discords. He was seated on the grass, in the garb of a sailor. At his right hand lay a square board, whereon was painted "a tale of woe," in letters that disdained the printer's art; at the top, a little box, with a glass cover, discovered that it was "plus" of what himself was "minus;" its inscription described its contents—"These bones was taken out of my leg." I could not withstand his claim to support. He was effecting the destruction of "Sweet Poll of Plymouth," for which I gave him a trifle more than his "fair" audience usually bestowed, perhaps. He instantly begged I would name my "favourite;" I desired to be acquainted with his; he said he could not "deny nothing to so noble a benefactor," and he immediately began to murder "Black-eyed Susan." If the man at the wall of the Fishmongers' almshouses were dead, he would be the worst player in England.

There were several parties playing at "Kiss in the ring," an innocent merriment in the country; here it was certainly not merriment. On the hill the runners were abundant, and the far greater number were, in appearance and manners, devoid of that vulgarity and grossness from whence it might be inferred that the sport was any way improper; nor did I observe, during a stay of several hours, the least indication of its being otherwise than a cheerful amusement. One of the prettiest sights was a game at "Thread my needle," played by about a dozen lasses, with a grace and glee that reminded me of Angelica's nymphs. I indulged a hope that the hilarity of rural pastimes might yet be preserved. There was no drinking in the park. It lost its visitants fast while the sun was going down. Many were arrested in their progress to the gate by the sight of the boys belonging to the college, who were at their evening play within their own grounds, and who, before they retired for the night, sung "God save the King," and "Rule Britannia," in full chorus, with fine effect.

The fair, or at least such part of it as was suffered to be continued, was held in the open space on the right hand of the street leading from Greenwich to the Creek bridge. "The Crown and Anchor" booth was the great attraction, as indeed well it might. It was a tent, three hundred and twenty-three feet long, and sixty feet wide. Seventy feet of this, at the entrance, was occupied by seats for persons who chose to take refreshment, and by a large space from whence the viands were delivered. The remaining two hundred and fifty feet formed the "Assembly room" wherein were boarded floors for four rows of dancers throughout this extensive length; on each side were seats and tables. The price of admission to the assembly was one shilling. The check ticket was a card, whereon was printed,

VAUXHALL.

CROWN AND ANCHOR,

WHIT MONDAY.This room was thoroughly lighted up by depending branches from the roofs handsomely formed; and by stars and festoons, and the letters G. R. and other devices, bearing illumination lamps. It was more completely filled with dancers and spectators, than were convenient to either. Neither the company nor the scene can be well described. The orchestra, elevated across the middle of the tent, consisting of two harps, three violins, a bass viol, two clarionets, and a flute, played airs from "Der Freishütz," and other popular tunes. Save the crowd, there was no confusion; save in the quality of the dancers and dancing, there was no observable difference between this and other large assemblies; except, indeed, that there was no master of the ceremonies, nor any difficulty in obtaining or declining partners. It was neither a dancing school, nor a school of morals; but the moralist might draw conclusions which would here, and at this time, be out of place. there were at least 2,000 persons in this booth at one time. In the fair were about twenty other dancing booths; yet none of them comparable in extent to the "Crown and Anchor." In one only was a price demanded for admission; the tickets to the "Albion Assembly" were sixpence. Most of these booths had names; for instance, "The Royal Standard;" "The Lads of the Village," "The Black Boy and Cat Tavern," "The Moon-rakers," &c. At eleven o'clock, stages from Greenwich to London were in full request. One of them obtained 4s. each for inside, and 2s. 6d. for outside passengers; the average price was 3s. inside, and 2s. outside; and though the footpaths were crowded with passengers, yet all the inns in Greenwich and on the road were thoroughly filled. Certainly, the greater part of the visitors were mere spectators of the scene.

*

NIGHT

The late Henry Kirke White, in a fragment of a poem on "Time," beautifully imagines the slumbers of the sorrowful. Reader, bear with its melancholy tone. A summer's day is not less lovely for a passing cloud.

Behold the world

Rests, and her tired inhabitants have paused

From trouble and turmoil. The widow now

Has ceased to weep, and her twin-orphans lie

Lock'd in each arm, partakers of her rest.

The man of sorrow has forgot his woes;

The outcast that his head is shelterless,

His griefs unshared. The mother tends no more

Her daughter's dying slumbers, but surprised

With heaviness, and sunk upon her couch,

Dreams of her bridals. Even the hectic lull'd

On Death's lean arm to rest, in visions wrapt,

Crowning with Hope's bland wreath his shuddering nurse,

Poor victim! smiles. — Silence and deep repose

Reign o'er the nations; and the warning voice

Of Nature utters audibly within

The general moral;— tells us that repose,

Deathlike as this, but of far longer span,

Is coming on us—that the weary crowds,

Who now enjoy a temporary calm,

Shall soon taste lasting quiet, wrapt around

With grave-clothes; and their achng restless heads

Mouldering in holes and corners unobserved

Till the last trump shall break their sullen sleep.

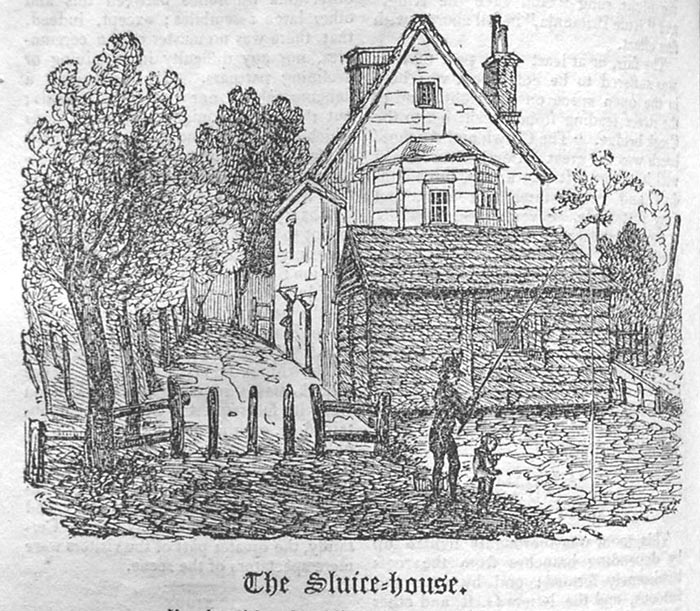

The Sluice-house.

Ye who with rod and line aspire to catch

Leviathans that swim within the stream

Of this fam'd River, now no longer New,

Yet still so call'd, come hither to the Sluice-house!

Here, largest gudgeons live, and fattest roach

Resort, and even barbel have been found.

Here too doth sometimes prey the rav'ning shark,

Of streams like this, that is to say, a jack.

If fortune aid ye, ye perchance shall find

Upon an average within one day,

At least a fish, or two; if ye do not,

This will I promise ye, that ye shall have

Most glorious nibbles: come then, haste ye here,

And with ye bring large stock of baits and patience.

From Canonbury tower onward by the New River, is a pleasant summer afternoon's walk. Highbury barn, or, as it is now called, Highbury tavern, is the first place of note beyond Canonbury. It was anciently a barn belonging to the ecclesiastics of Clerkenwell; though it is at present only known to the inhabitants of that suburb, by its capacity for filling them with good things in return for the money they spend there. The "barn" itself is the assembly-room, whereon the old roof still remains. This house has stood in the way of all passengers to the Sluice-house, and turned many from their firm-set purpose of fishing in the waters near it. Every man who carries a rod and line is not an Isaac Walton, whom neither blandishment nor obstacle could swerve from his mighty end, when he went forth to kill fish.

He was the great progenitor of all

That war upon the tenants of the stream,

He neither stumbled, stopt, nor had a fall

When he essay'd to war on dace, bleak, bream,

Stone-loach or pike, or other fish, I deem.The Sluice-house is a small wooden building, distant about half a mile beyond Highbury, just before the river angles off towards Newington. With London anglers it has always been a house of celebrity, because it is the nearest spot wherein they have hope of tolerable sport. Within it is now placed a machine for forcing water into the pipes that supply the inhabitants of Holloway, and other parts adjacent. Just beyond is the Eel-pie house, which many who angle thereabouts mistake for the Sluice-house. To instruct the uninformed, and to gratify the eye of some who remember the spot they frequented in their youth, the preceding view, taken in May 1825, has been engraved. If the artist had been also a portrait painter, it would have been well to have secured a sketch of the present keeper of the Sluice-house; his manly mien, and mild expressive face, are worthy of the pencil: if there be truth in physiognomy, he is an honest, good-hearted man. His dame, who tenders Barcelon nuts and oranges at the Sluice-house door for sale, with fishing-lines from two-pence to six-pence, and rods at a penny each, is somewhat stricken in years, and wholly innocent of the metropolis and its manners. She seems of the times—

"When our fathers pluck'd the blackberry

And sipp'd the silver tide."

An etching of the eccentric individual, from whence the present engraving is taken, was transmitted by a respectable "Cantab," for insertion in the Every-Day Book, with the few particulars ensuing:—

James Gordon was once a respectable solicitor in Cambridge, till "love and liquor"

"Robb'd him of that which once enriched him,

And made him poor indeed!"He is well known to many resident and non-resident sons of alma mater, as a déclamateur, and for ready wit and re partee, which few can equal. One or two instances may somewhat depict

Gordon meeting a gentleman in the streets of Cambridge who had recently received the honour of knighthood, Jemmy approached him, and looking him full in the face, exclaimed,

"The king, by merely laying sword on,

Could make a knight of Jemmy Gordon."At a late assize at Cambridge, a man named Pilgrim was convicted of horse-stealing, and sentenced to transportation. Gordon seeing the prosecutor in the street, loudly vociferated to him, "You, sir, have done what the pope of Rome cannot do; you have put a stop to Pilgrim's Progress!"

Gordon was met one day by a person of rather indifferent character, who pitied Jemmy's forlorn condition, (he being without shoes and stockings,) and said, "Gordon, if you will call at my house, I will give you a pair of shoes." Jemmy, assuming a contemptuous air, replied, "No, sir! excuse me, I would not stand in your shoes for all the world!"

Some months ago, Jemmy had the misfortune to fall from a hay-loft, wherein he had retired for the night, and broke his thigh; since then he has reposed in a workhouse. No man's life is more calculated

"To adorn a moral, and to point a tale."

N.

These brief memoranda suffice to memorialize a peculiar individual. James Gordon at one time possessed "fame, wealth, and honours:" Now—his "fame" is a hapless notoriety; all the "wealth" that remains to him is a form that might have been less careworn had he been less careless; his honour is "air—thin air," "his gibes, his jests, his flashes of merriment, that were wont to set the table in a roar," no longer enliven the plenteous banquet:—

"Deserted in his utmost need by men his former bounty fed,"

the bitter morsel for his life's support is parish dole. "The gayest of the gay" is forgotten in his age—in the darkness of life; when reflection on what was, cannot better what is. Brilliant circles of acquaintance sparkle with frivolity, but friendship has no place within them. The prudence of sensuality is selfishness. [1]

The Cambridge communication concerning James Gordon is accompanied by an amusing list of names derived from "men and things."

Personages and their Callings at Cambridge in 1825.

A King ... is ... a brewer

A Bishop ... a tailor

A Baron ... a horse-dealer

A Knight ... a turf-dealer

A Proctor ... a tailor

A Marshall ... a cheesemonger

An Earl ... a laundress

A Butler ... a picture-frame maker

A Page ... a bookbinder

A Pope ... an old woman

An Abbott ... a bonnet-maker

A Monk ... a waterman

A Nun ... a horse-dealer

A Moor ... a poulterer

A Savage ... a carpenter

A Scott ... an Englishman

A Rose ... a fishmonger

A Lilly ... a brewer

A Crab ... a butcher

A Salmon ... a linendraper

A Leech ... a fruiterer

A Pike ... a milkman

A Sole ... a shoemaker

A Wood ... a grocer

A Field ... a confectioner

A Tunnell ... a baker

A Marsh ... a carrier

A Brook ... a turf-dealer

A Greenwood ... a baker

A Lee ... an innkeeper

A Bush ... a carpenter

A Grove ... a shoemaker

A Lane ... a carpenter

A Green ... a builder

A Hill ... a butcher

A Haycock ... a publican

A Barne ... a grocer

A Shed ... a butler

A Hutt ... a shoeblack

A Hovel ... a draper

A Hatt ... a bookseller

A Capp ... a gardener

A Spencer ... a butcher

A Bullock ... a baker

A Fox ... a brazier

A Lamb ... a sadler

A Lion ... a grocer

A Mole ... a town-crier

A Roe ... an engraver

A Buck ... a college gyp.

A Hogg ... a gentleman

A Bond ... a grocer

A Binder ... a fruiterer

A Cock ... a shoemaker

A Hawk ... a paperhanger

A Drake ... a dissenting minister

A Swan ... a shoemaker

A Bird ... an innkeeper

A Peacock ... a lawyer

A Rook ... a tailor

A Wren ... a bricklayer's labourer

A Falcon ... a gentleman

A Crow ... a builder

A Pearl ... a cook

A Stone ... a glazier

A Cross ... a boatwright

A Barefoot ... an innkeeper

A Leg ... a mantua-maker

White ... a shoemaker

Green ... a carpenter

Brown ... a fishmonger

Grey ... a painter

Pink ... a publican

Tall ... a printer

Short ... a tailor

Long ... a shopkeeper

Christmas ... an ironmonger

Summer ... a carpenter

Sad ... a barber

Grief ... a glazier

Peace ... a carpenter

Bacon ... a tobacconist.

A Hard-man

A Wise-man

A Good-man

A Black-man

A Chap-man

A Free-man

A New-man

A Bow-man

A Spear-man

A Hill-man

A Wood-man

A Pack-man

A Pit-man

A Red-man

A True-man.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Lilac. Syringa vulgaris.

Dedicated to St. Julia.