April 5.

St. Vincent Ferrer, A.D. 1419. St. Gerald, Abbot, A.D. 1095. St. Tigernach, Bishop in Ireland, A.D. 550. St. Becan, Abbot.

EASTER TUESDAY.

Holidays at the Public Offices; except Excise, Stamp, and Custom.

CHRONOLOGY .

1605. John Stow, the antiquary, died, aged 80. He was a tailor.

1800. The rev. William Mason died. He was born at Hull, in Yorkshire, in 1725.

1804. The rev. William Gilpin, author of "Picturesque Tours," "Remarks on forest Scenery," an "Essay on Prints," &c. died aged 80.

1811. Robert Raikes, of Gloucester, died, aged 76. He was the originator of sunday-schools, and spent his life in acts of kindness and compassion; promoting education as a source of happiness to his fellow beings, and bestowing his exertions and bounty to benefit the helpless.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Yellow Crown Imperial. Fritillaria Imperialis Lutea.

Dedicated to St. Vincent Ferrer.

Easter Customs.

Dancing of the Sun.

The day before Easter-day is in some parts called "Holy Saturday." On the evening of this day, in the middle districts of Ireland, great preparations are made for the finishing of Lent. Many a fat hen and dainty piece of bacon is put in the pot by the cotter's wife about eight or nine o'clock, and woe be to the person who should taste it before the cock crows. At twelve is heard the clapping of hands, and the joyous laugh, mixed with "Shidth or mogh or corries," i. e. out with the Lent: all is merriment for a few hours, when they retire, and rise about four o'clock to see the sun dance in honour of the resurrection. This ignorant custom is not confined to the humble labourer and his family, but is scrupulously observed by many highly respectable and wealthy families, different members of whom I have heard assert positively that they had seen the sun dance on Easter morning.*[1]

It is inquired in Dunton's "Athenian Oracle," "Why does the sun at his rising play more on Easter-day than Whit-Sunday?" The question is answered thus:— "The matter of fact is an old, weak, superstitious error, and the sun neither plays nor works on Easter-day more than any other. It is true, it may sometimes happen to shine brighter that morning than any other; but, if it does, it is purely accidental. In some parts of England they call it the lamb-playing, which they look for, as soon as the sun rises, in some clear or spring water, and is nothing but the pretty reflection it makes from the water, which they may find at any time, if the sun rises clear, and they themselves early, and unprejudiced with fancy." The folly is kept up by the fact, that no one can view the sun steadily at any hour, and those who choose to look at it, or at its reflection in water, see it apparently move, as they would on any other day. Brand points out an allusion to this vulgar notion in an old ballad:—

But, Dick, She dances such away!

No sun upon an Easter-day

Is half so fine a sight.Again, from the "British Apollo," a presumed question to the sun himself upon the subject, elicits a suitable answer:

Q. Old Wives, Phœbus, say

That on Easter-day

To the music o' th' spheres you do caper;

If the fact, sir, be true,

Pray let's the cause know,

When you have any room in your paper.A. The old wives get merry

With spic'd ale or sherry,

On Easter, which makes them romance;

And whilst in a rout

Their brains whirl about,

They fancy we caper and dance.A bit of smoked glass, such as boys use to view an eclipse with, would put this matter steady to every eye but that of wilful self-deception, which, after all, superstition always chooses to see through.

Lifting.

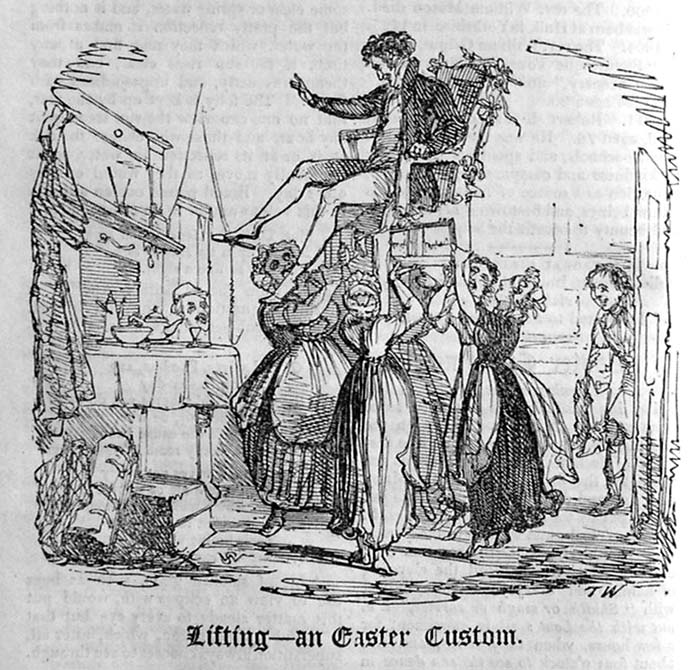

Mr. Ellis inserts, in his edition of Mr. Brand's "Popular Antiquities," a letter from Mr. Thomas Loggan of Basinghall-street, from whence the following extract is made: Mr. Loggan says, "I was sitting alone last Easter tuesday, at breakfast, at the Talbot in Shrewsbury, when I was surprised by the entrance of all the female servants of the house handing in an armchair, lined with white, and decorated with ribbons and favours of different colours. I asked them what they wanted, their answer was, they came to heave me; it was the custom of the place on that morning, and they hoped I would take a seat in their chair. It was impossible not to comply with a request very modestly made, and to a set of nymphs in their best apparel, and several of them under twenty. I wished to see all the ceremony, and seated myself accordingly. The group then lifted me from the ground, turned the chair about, and I had the felicity of a salute from each. I told them, I supposed there was a fee due upon the occasion, and was answered in the affirmative; and, having satisfied the damsels in this respect, they withdrew to heave others. At this time I had never heard of such a custom; but, on inquiry, I found that on Easter Monday, between nine and twelve, the men heave the women in the same manner as on the Tuesday, between the same hours, the women heave the men."

Lifting—an Easter Custom

In Lancashire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire, and some other parts of England there prevails this custom of heaving or lifting at Easter-tide. This is perfromed mostly in the open street, though sometimes it is insisted on and submitted to within the house. People form into parties of eight or a dozen or even more for the purpose, and from every one lifted or heaved they extort a contribution. The late Mr. Lysons read to the Society of Antiquaries an extract from a roll in his custody, as keeper of the records in the tower of London, which contains a payment to certain ladies and maids of honour for taking king Edward I. in his bed at Easter; from whence it has been presumed the he was lifted on the authority of that custom, which is said to have prevailed among all ranks throughout the kingdom. The usage is a vulgar commemoration of the resurrection which the festival of Easter celebrates.

Lifting or heaving differs a little in different places. In some parts the person is laid horizontally, in others placed in a sitting position on the bearers' hands. Usually, when the lifting or heaving is within doors, a chair is produced, but in all cases the ceremony is incomplete without three distinct elevations.

A Warwickshire correspondent, L. S., says, Easter Monday and Easter Tuesday were known by the name of heaving-day, because on the former day it was customary for the men to heave and kiss the women, and on the latter for the women to retaliate upon the men. the womens' heaving-day was the most amusing. Many a time have I passed along the streets inhabited by the lower orders of people, and seen parties of jolly matrons assembled round tables on which stood a foaming tankard of ale. There they sat in all the pride of absolute sovereignty, and woe to the luckless man that dared to invade their prerogatives!—as sure as he was seen he was pursued—as sure as he was pursued he was taken—and as sure as he was taken he was heaved and kissed, and compelled to pay sixpence for "leave and license" to depart.

Conducted as lifting appears to have been by the blooming lasses of Shrewsbury, and acquitted as all who are actors in the usage any where must be, of even the slightest knowledge that this practice is an absurd performance of the resurrection, still it must strike the reflective mind as at least an absurd custom, "more honored i' the breach than the observance." It has been handed down to us from the bewildering ceremonies of the Romish church, and may easily be discountenanced into disuse by opportune and mild persuasion. If the children of ignorant persons be properly taught, they will perceive in adult years the gross follies of their parentage, and so instruct their own offspring, that not a hand or voice shall be lifted or heard from the sons of labour, in support of a superstition that darkened and dismayed man, until the printing-press and the reformation ensured his final enlightenment and emancipation.

Easter Eggs.

Another relic of the ancient times, are the eggs which pass about at Easter week under the name of pask, paste, or pace eggs. A communication introduces the subject at once.

To the Editor of the Every-Day Book.

19th March, 1825

Sir,

A perusal of the Every-Day Book induces me to communicate the particulars of a custom still prevalent in some parts of Cumberland, although not as generally attended to as it was twenty or thirty years ago. I allude to the practice of sending reciprocal presents of eggs, at Easter, to the children of families respectively, betwixt whom any intimacy subsists. For some weeks preceding Good Friday the price of eggs advances considerably, from the great demand occasioned by the custom referred to.The modes adopted to prepare the eggs for presentation are the following: there may be others which have escaped my recollection.

The eggs being immersed in hot water for a few moments, the end of a common tallow-candle is made use of to inscribe the names of individuals, dates of particular events, &c. The warmth of the egg renders this a very easy process. Thus inscribed, the egg is placed in a pan of hot water, saturated with cochineal, or other dye-woods; the part over which the tallow has been passed is impervious to the operation of the dye; and consequently when the egg is removed from the pan, there appears no discolouration of the egg where the inscription has been traced, but the egg presents a white inscription on a coloured ground. The colour of course depends upon the taste of the person who prepared the egg; but usually much variety of colour is made use of.

Another method of ornamenting "pace eggs" is, however, much neater, although more laborious, than that with the tallow-candle. The egg being dyed, it may be decorated in a very pretty manner, by means of a penknife, with which the dye may be scraped off, leaving the design white, on a coloured ground. An egg is frequently divided into compartments, which are filled up according to the taste and skill of the designer. Generally one compartment contains the name and (being young and unsophisticated) also the age of the party for whom the egg is intended. In another is, perhaps, a landscape; and sometimes a cupid is found lurking in a third: so that these "pace eggs" become very useful auxiliaries to the missives of St. Valentine. Nothing was more common in the childhood of the writer, than to see a number of these eggs preserved very carefully in the corner-cupboard; each egg being the occupant of a deep, long-stemmed ale-glass, through which the inscription could be read without removing it. Probably many of these eggs now remain in Cumberland, which would afford as good evidence of dates in a court of justice, as a tombstone or a family-bible.

It will be readily supposed that the majority of pace aggs are simply dyed; or dotted with tallow to present a pie-bald or bird's-eye appearance. These are designed for the junior boys who have not begun to participate in the pleasures of "a bended bow and quiver full of arrows;"—a flaming torch, or a heart and a true-lover's knot. These plainer specimens are seldom promoted to the dignity of the ale-glass or the corner-cupboard. Instead of being handed down to posterity they are hurled to swift destruction. In the process of dying they are boiled pretty hard— so as to prevent inconvenience if crushed in the hand or the pocket. But the strength of the shell constitutes the chief glory of a pace egg, whose owner aspires only to the conquest of a rival youth. Holding his egg in his hand he challenges a companion to give blow for blow. One of the eggs is sure to be broken, and its shattered remains are the spoil of the conqueror: who is instantly invested with the title of "a cock of one, two, three," &c. in proportion as it may have fractured his antagonist's eggs in the conflict. A successful egg, in a contest with one which had previously gained honours, adds to its number the reckoning of its vanquished foe. An egg which is a "cock" of ten or a dozen, is frequently challenged. A modern pugilist would call this a set-to for the championship. Such on the borders of the Solway Frith were the youthful amusements of Easter Monday.

Your very proper precaution, which requires the names of correspondents who transmit notices of local customs, is complied with by the addition of my name and address below. In publication I prefer to appear only as your constant reader. J. B.

A notice below, the editor hopes will be read and taken by the reader, for whose advantage it is introduced, in good part.* [2]

Pasch eggs are to be found at Easter in different parts of the kingdom. A Liverpool gentleman informs the editor, that in that town and neighbourhood they are still common, and called paste eggs. One of his children brought to him a paste egg at Easter, 1824, beautifully mottled with brown. It had been purposely prepared for the child by the servant, by being boiled hard within the coat of an onion, which imparted to the shell the admired colour. Hard boiling is a chief requisite in preparing the pasch egg. In some parts they are variously coloured with the juices of different herbs, and played with by boys, who roll them on the grass, or toss them up for balls. Their more elegant preparation is already described by our obliging correspondent, J. B.

The terms pace, paste, or pasch, are derived from paschal, which is a name given to Easter from its being the paschal season. Four hundred eggs were bought for eighteen-pence in the time of Edward I., as appears by a royal roll in the tower; from whence it also appears they were purchased for the purpose of being boiled and stained, or covered with leaf gold, and afterwards distributed to the royal household at Easter. They were formerly consecrated, and the ritual of pope Paul V. for the use of England, Scotland, and Ireland, contains the form of consecration.* [3] On Easter eve and Easter day, the heads of families sent to the church large chargers, filled with the hard boiled eggs, and there the "creature of eggs" became sacred by virtue of holy water, crossing and so on.

Ball. Bacon. Tansy Puddings.

Eating of tansy pudding is another custom at Easter derived from the Romish church. Tansy symbolized the bitter herbs used by the Jews at their paschal; but that the people might show a proper abhorrence of Jews, they ate from a gammon of bacon at Easter, as many still do in several country places, at this season, without knowing from whence this practice is derived. Then we have Easter ball-play, another ecclesiastical device, the meaning of which cannot be quite so clearly traced; but it is certain that the Romish clergy abroad played at ball in the church, as part of the service; and we find an archbishop joining in the sport. "A ball, not of size to be grasped by one hand only, being given out at Easter, the dean and his representatives began an antiphone, suited to Easter-day; then taking the ball in his left hand, he commenced a dance to the tune of the antiphone, the others dancing round hand in hand. At intervals, the ball was bandied or passed to each of the choristers. The organ played according to the dance and sport. The dancing and antiphone being concluded, the choir went to take refreshment. It was the privilege of the lord, or his locum tenens, to throw the ball; even the archbishop did it."† [4] Whether the dignified clergy had this amusement in the English churches is not authenticated; but it seems that "boys used to claim hard, eggs, or small money, at Easter, in exchange for the ball-play before mentioned."* [5] Brand cites the mention of a lay amusement at this season, wherein both tansy and ball-play is referred to.

Stool-ball.

At stool-ball, Lucia, let us play,

For sugar, cakes, or wine.

Or for a tansy let us pay,

The loss be thine or mine.

If thou, my dear, a winner be

At trundling of the ball,

The wager thou shall have, and me,

And my misfortunes all.1679.

Also, from "Poor Robin's Almanack" for 1677, this Easter verse, denoting the sport at that season:

Young men and maids,

Now very brisk,

At barley-break and

Stool-ball frisk.A ball custom now prevails annually at Bury St. Edmund's, Suffolk. On Shrove Tuesday, Easter Monday, and the Whitsuntide festivals, twelve old women side off for a game at trap-and-ball, which is kept up with the greatest spirit and vigour until sunset. One old lady, named Gill, upwards of sixty years of age, has been celebrated as the "mistress of the sport" for a number of years past; and it affords much of the good old humour to flow round, whilst the merry combatants dextrously hurl the giddy ball to and fro. Afterwards they retire to their homes, where

"Voice, fiddle, or flute,

No longer is mute,"and close the day with apportioned mirth and merriment.† [6]

Corporations formerly went forth to play at ball at Easter. Both then and at Whitsuntide, the mayor, aldermen, and sheriff of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, with a great number of the burgesses, went yearly to the Forth, or little mall of the town, with the mace, sword, and cap of maintenance, carried before them, and patronised the playing at hand-ball, dancing, and other amusements, and sometimes joined in the ball-play, and at others joined hands with the ladies.

There is a Cheshire proverb, "When the daughter is stolen, shut the Pepper-gate." This is founded on the fact that the mayor of Chester had his daughter stolen as she was playing at ball with other maidens in Pepper-street; the young man who carried her off, came through the Pepper-gate, and the mayor wisely ordered the gate to be shut up:* [7] agreeable to the old saying, and present custom agreeable thereto, "When the steed's stolen, shut the stable-door." Hereafter it will be seen that persons quite as dignified and magisterial as mayors and aldermen, could compass a holiday's sport and a merry-go-round, as well as their more humble fellow subjects.

Clipping the Church at Easter.

L. S., a Warwickshire correspondent, communicates this Easter custom to the Every-Day Book:

"When I was a child, as sure as Easter Monday came, I was taken 'to see the children clip the churches.' This ceremony was performed, amid crowds of people and shouts of joy, by the children of the different charity-schools, who at a certain hour flocked together for the purpose. The first comers placed themselves hand in hand with their backs against the church, and were joined by their companions, who gradually increased in number, till at last the chain was of sufficient length completely to surround the sacred edifice. As soon as the hand of the last of the train had grasped that of the first, the party broke up, and walked in procession to the other church, (for in those days Birmingham boasted but of two,) where the ceremony was repeated."

Old Easter Customs in Church.

In the celebration of this festival, the Romish church amused our forefathers by theatrical representations, and extraordinary dramatic worship, with appropriate scenery, machinery, dresses, and decorations. The exhibitions at Durham appear to have been conducted with great effect. In that cathedral, over our lady of Bolton's altar, there was a marvellous, lively, and beautiful image of the picture of our lady, called the lady of Bolton, which picture was made to open with gimmes, (or linked fastenings,) from the breast downward; and within the said image was wrought and pictured the image of our saviour marvellously finely gilt, holding up his hands, and betwixt his hands was a large fair crucifix of Christ, all of gold; the which crucifix was ordained to be taken forth every Good Friday, and every man did creep into it that was in the church at that time; and afterwards it was hung up again within the said image. Every principal day the said image of our lady of Bolton, was opened, that every man might see pictured within her, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, most curiously and finely gilt; and both the sides within her were very finely varnished with green varnish, and flowers of gold, which was a goodly sight for all the beholders thereof. On Good Friday, there was marvellous solemn service, in which service time, after the Passion was sung, two of the ancient monks took a goodly large crucifix, all of gold, of the picture of our saviour Christ nailed upon the cross, laying it upon a velvet cushion, having St. Cuthbert's arms upon it, all embroidered with gold, bringing it betwixt them upon the cushion to the lowest steps in the choir, and there betwixt them did hold the said picture of our saviour, sitting on either side of it. And then one of the said monks did rise, and went a pretty space from it, and setting himself upon his knees with his shoes put off, very reverently he crept upon his knees unto the said cross, and most reverently did kiss it; and after him the other monk did so likewise; and then they sate down on either side of the said cross, holding it betwixt them. Afterward, the prior came forth of his stall, and did sit him down upon his knees with his shoes off in like sort, and did creep also unto the said cross, and all the monks after him did creep one after another in the same manner and order; in the mean time, the whole choir singing a hymn. The service being ended, the said two monks carried the cross to the sepulchre with great reverence.*[8]

The sepulchre was erected in the church near the altar, to represent the tomb wherein the body of Christ was laid for burial. At this tomb there was a grand performance on Easter-day. In some churches it was ordained, that Mary Magdalen, Mary of Bethany, and Mary of Naim, should be represented by three deacons clothed in dalmaticks and amesses, with their heads in the manner of women, and holding a vase in their hands. These performers came through the middle of the choir, and hastening towards the sepulchre, with downcast looks, said together this verse, "Who will remove the stone for us?" Upon this a boy, clothed like an angel, in albs, and holding a wheat ear in his hand, before the sepulchre, said, "Whom do you seek in the sepulchre?" The Maries answered "Jesus of Nazareth who was crucified." The boy-angel answered, "He is not here, but is risen;" and pointed to the place with his finger. The boy-angel departed very quickly, and two priests in tunics, sitting without the sepulchre, said, "Woman, whom do ye mourn for? Whom do ye seek?" the middle one of the women said, "Sir, if you have taken him away, say so." The priest, showing the cross, said, "They have taken away the Lord." The two sitting priests said, "Whom do ye seek, women?" The Maries, kissing the place, afterwards went from the sepulchre. In the mean time a priest, in the character of Christ, in an alb, with a stole, holding a cross, met them on the left horn of the altar, and said, "Mary!" Upon hearing this, the mock Mary threw herself at his feet, and, with a loud voice, cried Cabboin. The priest representing Christ replied, nodding, "Noli me tangere," touch me not. This being finished, he again appeared at the right horn of the altar, and said to them as they passed before the altar, "Hail! do not fear." This being finished, he concealed himself; and the women-priests, as though joyful at hearing this, bowed to the altar, and turning to the choir, sung "Alleluia, the Lord is risen." This was the signal for the bishop or priest before the altar, with the censer, to begin and sing aloud, Te Deum.* [9]

The making of the sepulchre was a practice founded upon ancient tradition, that the second coming of Christ would be on Easter-eve; and sepulchre-making, and watching it, remained in England till the reformation. Its ceremonies varied in different places. In the abbey church of Durham it was part of the service upon Easter-day, betwixt three and four o'clock in the morning, for two of the eldest monks of the quire to come to the sepulchre, set up upon Good Friday after the Passion, which being covered with red velvet, and embroidered with gold, these monks, with a pair of silver censers, censed the sepulchre on their knees. Then both rising, went to the sepulchre, out of which they took a marvellous beautiful image of the resurrection, with a cross in the hand of the image of Christ, in the breast whereof was inclosed, in bright crystal, the host, so as to be conspicuous to the beholders. Then, after the elevation of the said picture, it was carried by the said two monks, upon a velvet embroidered cushion, the monks singing the anthem of Christus resurgens. They then brought it to the high altar, setting it on the midst thereof, and the two monks kneeling before the altar, censed it all the time that the rest of the quire were singing the anthem, which being ended, the two monks took up the cushion and picture from the altar, supporting it betwixt them, and proceeded in procession from the high altar to the south quire door, where there were four ancient gentlemen belonging to the quire, appointed to attend their coming, holding up a rich canopy of purple velvet, tasselled round about with red silk and gold fringe; and then the canopy was borne by these "ancient gentlemen," over the said images with the host carried by the two monks round the church, the whole quire following, with torches and great store of other lights; all singing, rejoicing, and praying, till they came to the high altar again; upon which they placed the said image, there to remain till Ascension-day, when another ceremony was used.

In Brand's "Antiquities," and other works, there are many items of expenses from the accounts of different church-books for making the sepulchre for this Easter ceremony. The old Register Book of the brethren of the Holy Trinity of St. Botolph without Aldersgate, now in the possession of the editor of the Every-Day Book, contains the following entries concerning the sepulchre in that church:— "Item, to the wexchaundler, for makyng of the Sepulcre light iii times, and of other dyvers lights that longyn to the trynite, in dyvers places in the chirche, lvii s. 10 d ." In An. 17 Henry VI. there is another "Item, for xiii tapers unto the lyght about the Sepulcre, agenst the ffeste of Estern, weying lxxviii lb. of the wich was wasted xxii lb." &c. In Ann. 21 & 22 K. Henry VI. the fraternity paid for wax and for lighting of the sepulchre "both yers, xx s. viii d." and they gathered in those years for their sepulchre light, xlv s. ix d. This gathering was from the people who were present at the representation; and when the value of money at that time is considered, and also that on the same day every church in London had a sepulchre, each more or less attractive, the sum will not be regarded as despicable.

The only theatres for the people were churches, and the monks were actors; accordingly, at Easter, plays were frequently got up for popular amusement. Brand cites from the churchwardens' accounts of Reading, set forth in Coate's history of that town, several items of different sums paid for nails for the sepulchre; "for rosyn to the Resurrection play;" for setting up off poles for the scaffold whereon the plays were performed; for making "a Judas;" for the writing of the plays themselves; and for other expenses attending the "getting up" of the representations. Though the subjects exhibited were connected with the incidents commemorated by the festival, yet the most splendid shows must have been in those churches which performed the resurrection at the sepulchre with a full dramatis personæ of monks, in dresses according to the characters they assumed.

Mr. Fosbroke gives the "properties" of the sepulchre show belonging to St. Mary Redcliff's church at Bristol, from an original MS. in his possession formerly belonging to Chatterton, viz. "Memorandum:— That master Cannings hath delivered, the 4th day of July, in the year of our Lord 1470, to master Nicholas Pelles, vicar of Redclift, Moses Conterin, Philip Berthelmew, and John Brown, procurators of Redclift beforesaid, a new Sepulchre, well guilt with fine gold, and a civer thereto; an image of God Almighty rising out of the same Sepulchre, with all the ordinance that longeth thereto; that is to say, a lath made of timber and iron work thereto. Item, hereto longeth Heven, made of timber and stained cloths. Item, Hell made of timber and iron work thereto, with Devils the number of thirteen. Item, four knights armed, keeping the Sepulchre, with their weapons in their hands; that is to say, two spears, two axes, with two shields. Item, four pair of Angel's wings, for four Angels, made of timber, and well-painted. Item, the Fadre, the crown and visage, the ball with a cross upon it, well gilt with fine gold. Item, the Holy Ghost coming out of Heven into the Sepulchre. Item, longeth to the four Angels, four Perukes." The lights at the sepulchre shows, and at Easter, were of themselves a most attractive part of the Easter spectacle. The paschal or great Easter taper at Westminster Abbey was three hundred pounds' weight. Sometimes a large wax light called a serpent was used; its name was derived from its spiral form, it being wound round a rod. To light it, fire was struck from a flint consecrated by the abbot. The paschal in Durham cathedral was square wax, and reached to within a man's length of the roof, from whence this waxen enormity was lighted by "a fine convenience." From this superior light all others were taken. Every taper in the church was purposely extinguished in order that this might supply a fresh stock of consecrated light, till at the same season in the next year a similar parent torch was prepared.* [10]

EASTER IN LONDON.

Easter Monday and Tuesday, and Greenwich fair, are renowned as "holidays" throughout most manufactories and trades conducted in the metropolis. On Monday, Greenwich fair commences. The chief attraction to this spot is the park, wherein stands the Royal Observatory on a hill, adown which it is the delight of boys and girls to pull each other till they are wearied. Frequently of late this place has been a scene of rude disorder. But it is still visited by thousands and tens of thousands from London and the vicinity; the lowest join in the hill sports; others regale in the public-houses; and many are mere spectators, of what may be called the humours of the day.

On Easter Monday, at the very dawn of day, the avenues from all parts towards Greenwich give sign of the first London festival in the year. Working men and their wives; 'prentices and their sweethearts; blackguards and bullies; make their way to this fair. Pickpockets and their female companions go later. The greater part of the sojourners are on foot, but the vehicles for conveyance are unnumerable. The regular and irregular stages are, of course, full inside and outside. Hackney-coaches are equally well filled; gigs carry three, not including the driver; and there are countless private chaise-carts, public pony-chaises, and open accommodations [sic]. Intermingled with these, town-carts, usually employed in carrying goods, are now fitted up, with boards for seats; hereon are seated men, women, and children, till the complement is complete, which is seldom deemed the case till the horses are overloaded. Now and then passes, like "some huge admiral," a full-sized coal-waggon, laden with coal-heavers and their wives, and shadowed by spreading boughs from every tree that spreads a bough; these solace themselves with draughts of beer from a barrel aboard, and derive amusement from criticising walkers, and passengers in vehicles passing their own, which is of unsurpassing size. The six-mile journey of one of these machines is sometimes prolonged from "dewy morn" till noon. It stops to let its occupants see all that is to be seen on its passage; such as what are called the "Gooseberry fairs," by the wayside, whereat heats are run upon half-killed horses, or spare and patient donkeys. Here are the bewitching sounds to many a boy's ears of "A halfpenny ride O!" "A halfpenny ride O!"; upon that sum "first had and obtained," the immediately bestrided urchin has full right to "work and labour" the bit of life he bestraddles, for the full space or distance of fifty yards, there and back; the returning fifty being done within half time of the first. Then there is "pricking in the belt," an old exposed and still practised fraud. Besides this, there are numberless invitations to take "a shy for a halfpenny," at a "bacca box, full o' ha'pence," standing on a stick stuck upright in the earth at a reasonable distance for experienced throwers to hit, and therefore win, but which is a mine of wealth to the costermonger proprietor, from the number of unskilled adventurers.

Greenwich fair, of itself, is nothing; the congregated throngs are every thing, and fill every place. The hill of the Observatory, and two or three other eminences in the park, are the chief resort of the less experienced and the vicious. But these soon tire, and group after group succeeds till evening. Before then the more prudent visitors have retired to some of the numerous houses in the vicinage of the park, whereon is written, "Boiling water here," or "Tea and Coffee," and where they take such refreshment as these places and their own bundles afford, preparatory to their toil home after their pleasure.

At nightfall, "Life in London," as it is called, is found at Greenwich. Every room in every public-house is fully occupied by drinkers, smokers, singers and dancers, and the "balls" are kept up during the greater part of the night. The way to town is now an indescribable scene. The vehicles congregated by the visitors to the fair throughout the day resume their motion, and the living reflux on the road is dense to uneasiness. Of all sights the most miserable is that of the poor broken-down horse, who having been urged three times to and from Greenwich with a load thither of pleasure-seekers at sixpence per head, is now unable to return, for the fourth time, with a full load back, through whipped and lifted, and lifted and whipped, by a reasoning driver, who declares "the hoss did it last fair, and why shouldn't he do it again." The open windows of every house for refreshment on the road, and clouds of tobacco-smoke therefrom, declare the full stowage of each apartment, while jinglings of the bells, and calls "louder and louder yet," speak wants and wishes to waiters, who disobey the instructions of the constituent bodies that sent them to the bar. Now from the wayside booths fly out corks that let forth "pop" and "ginger-beer," and little party-coloured lamps give something of a joyous air to appearances that fatigure and disgust. Overwearied children cry before they have walked to the halfway house; women with infants in their arms pull along their tipsey well-beloveds, others endeavour to wrangle or drag them out of drinking rooms, and, until long after midnight, the Greenwich road does not cease to disgorge incongruities only to be rivalled by the figures and exhibitions in Dutch and Flemish prints.

While this turmoil, commonly called pleasure-taking, is going on, there is another order of persons to whom Easter affords real recreation. Not less inclined to unbend than the frequenters of Greenwich, they seek and find a mode of spending the holiday-time more rationally, more economically, and more advantageously to themselves and their families. With their partners and offspring they ride to some of the many pleasant villages beyond the suburbs of London, out of the reach of the harm and strife incident to mixing with noisy crowds. Here the contented groups are joined by relations or friends, who have appointed to meet them, in the quiet lanes or sunny fields of these delightful retreats. When requisite, they recruit from well-stored junket baskets, carried in turn; and after calmly passing several hours in walking and sauntering through the open balmy air of a spring-day, they sometimes close it by making a good comfortable teaparty at a respectable house on their way to town. Then a cheerful glass is ordered, each joins in merry conversation, or some one suspected of a singing face justifies the suspicion, and "the jocund song goes round," till, the fathers being reminded by the mothers, more than once possibly, that "it's getting late," they rise refreshed and happy, and go home. Such an assembly is composed of honest and industrious individuals, whose feelings and expressions are somewhat, perhaps, represented below.

INDEPENDENT MEN

A HOLIDAY SONG.

We're independent men, with wives, and sweethearts, by our side,

We've hearts at rest, with health we're bless'd, and, being Easter tide,

We make our spring-time holiday, and take a bit of pleasure,

And gay as May, drive care away, and give to mirth our leisure.It's for our good, that thus, my boys, we pass the hours that stray,

We'll have our frisk, without the risk of squabble or a fray;

Let each enjoy his pastime so, that, without fear or sorrow,

When all his fun is cut and run, he may enjoy to-morrow.To-morrow may we happier be for happiness to-day,

That child or man, no mortal can, or shall, have it to say,

That we have lost both cash and time, and been of sense bereft,

For what we've spent we don't relent, we've time and money left.And we will husband both, my boys, and husband too our wives;

May sweethearts bold, before they're old, be happy for their lives;

For good girls make good wives, my boys, and good wives make men better,

When men are just, and scorning trust, each man is no man's debtor.Then at this welcome season, boys, let's welcome thus each other,

Each kind to each, shake hands with each, each be to each a brother;

Next Easter holiday may each again see flowers springing,

And hear birds sing, and sing himself, while merry bells are ringing.The clear open weather during the Easter holidays in 1825, drew forth a greater number of London holiday keepers than the same season of many preceding years. They were enabled to indulge by the full employment in most branches of trade and manufacture; and if the period was spent not less merrily, it was enjoyed more rationally and with less excess than before was customary. Greenwich, though crowded, was not so abundant of boisterous rudeness. "It is almost the only one of the popular amusements that remains: Stepney, Hampstead, Westend, and Peckham fairs have been crushed by the police, that 'stern, rugged nurse' of national morality; and although Greenwich fair continues, it is any thing but what it used to be. Greenwich, however, will always have a charm: the fine park remains—trees, glades, turf, and the view from the observatory, one of the noblest in the world—before you the towers of these palaces built for a monarch's residence, now ennobled into a refuge from life's storms for the gallant defenders of their country, after their long and toilsome pilgrimage—then the noble river; and in the distance, amidst the din and smoke, appears the 'mighty heart' of this mighty empire; these are views worth purchasing at the expense of being obliged to visit Greenwich fair in this day of its decline. 'Punch' and his 'better half' seemed to be the presiding deities in the fair, so little of merriment was there to be found. In the park, however, the scene was different; it was nearly filled with persons of all ages: the young came there for amusement, to see and be seen—the old to pay their customary annual visit. On the hills was the usual array of telescopes; there were also many races, and many sovereigns in the course of the day changed hands on the event of them; but one race in particular deserves remark, not that there was any thing in the character, appearance, or speed of the competitors, to distinguish them from the herd of others; the circumstances in it that afforded amusement was the dishonesty of the stakeholder, who, as the parties had just reached the goal, scampered off with the stakes, amidst the shouts of the by-standers, and the ill-concealed chagrin of the two gentlemen who had foolishly committed their money to the hands of a stranger." *[11]

According to annual custom on Easter Monday, the minor theatres opened on that day for the season, and were thronged, as usual, by spectators of novelties, which the Amphitheatre, the Surrey theatre, Sadler's-wells, and other places of dramatic entertainment, constantly get up for the holiday-folks. The scene of attraction was much extended, by amusements long before announced at distant suburbs. At half-past five on Monday afternoon, Mr. Green accompanied by one of his brothers, ascended in a balloon from the Eagle Tavern, the site of the still remembered "Shepherd and Shepherdess," in the City-road. "The atmosphere being extremely calm, and the sun shining brightly, the machine, after it had ascended to a moderate height, seemed to hang over the city for nearly half an hour, presenting a beautiful appearance, as its sides glistened with the beams of that orb, towards which it appeared to be conveying two of the inhabitants of a different planet." It descended near Ewell in Surrey. At a distance of ten miles from this spot, Mr. Graham, another aërial navigator, let off another balloon from the Star and Garter Tavern, near Kew-bridge. "During the preparations, the gardens began to fill with a motley company of farmers' families, and tradesmen from the neighbourhood, together with a large portion of city folks, and a small sprinkle of some young people of a better dressed order. The fineness of the day gave a peculiar interest to the scene, which throughout was of a very lively description. Parties of ladies, sweeping the 'green sward,' their gay dresses, laughing eyes, and the cloudless sky, make every thing look gay. Outside, it was a multitude, as far as the eye could see on one side. The place had the appearance of a fair, booths and stalls for refreshments being spread out, as upon these recreative occasions. Carts, drays, coaches, and every thing which could enable persons the better to overlook the gardens, were put into eager requisition, and every foot of resting-room upon Kew-bridge had found an anxious and curious occupant. In the mean time, fresh arrivals were taking place from all directions, but the clouds of dust which marked the line of the London-road, in particular, denoted at once the eagerness and numbers of the new comers. A glimpse in that direction showed the pedestrians, half roasted with the sun, and half suffocated with the dust, still keeping on their way towards the favoured spot. About five o'clock, Mr. Graham having seated himself in the car of his vehicle, gave the signal for committing the machine to its fate, She swung in the wind for a moment, but suddenly righting, shot up in a directly perpendicular course, amidst the stunning shout of the assembled multitude, Mr. Graham waving the flags and responding to their cheers. Nothing could be more beautiful than the appearance of the balloon at the distance of about a mile from the earth, for from reflecting back the rays of the sun, it appeared a solid body of gold suspended in the air. It continued in sight nearly an hour and a half; and the crowd, whose curiosity had brought them together, had not entirely dispersed from the gardens before seven o'clock. On the way home they were gratified with the sight of Mr. Green's balloon, which was seen distinctly for a considerable time along the Hammersmith-road. The shadows of evening were lengthening, and

—— midst falling dew,

While glow the Heavens with the last steps of day,

Far through their rosy depths it did pursue

Its solitary way." *[12]

SPITAL SERMONS.

In London, on Easter Monday and Tuesday, the Spital Sermons are preached. "On Easter Monday, the boys of Christ's Hospital walk in procession, accompanied by the masters and steward, to the Royal Exchange, from whence they proceed to the Mansion-house, where they are joined by the lord mayor, the lady mayoress, the sheriffs, aldermen, recorder, chamberlain, town clerk, and other city officers, with their ladies. From thence the cavalcade proceeds to Christ church, where the Spital Sermon is preached, always by one of the bishops, and an anthem sung by the children. His lordship afterwards returns to the Mansion-house, where a grand civic entertainment is prepared, which is followed by an elegant ball in the evening.

On Easter Tuesday, the boys again walk in procession to the Mansion-house, but, instead of the masters, they are accompanied by the matron and nurses. On Monday, they walk in the order of the schools, each master being at the head of the school over which he presides; and the boys in the mathematical school carry their various instruments. On Tuesday, they walk in the order of the different wards, the nurses walking at the head of the boys under her immediate care. On their arrival at the Mansion-house, they have the honour of being presented individually to the lord mayor, who gives to each boy a new sixpence, a glass of wine, and two buns. His lordship afterwards accompanies them to Christ church, where the service is the same as on Monday. The sermon is on Tuesday usually preached by his lordship's chaplain."* [13]

The most celebrated Spital Sermon of our times, was that preached by the late Dr. Samuel Parr, upon Easter Tuesday, 1800, against "the eager desire of paradox; the habit of contemplating a favourite topic in one distinct and vivid point of view, while it is disregarded under all others; a fondness for simplicity on subjects too complicated in their inward structure on their external relations, to be reduced to any single and uniform principle;" and against certain speculations on "the motives by which we are impelled to do good to our fellow creatures, and adjusting the extent to which we are capable of doing it." This sermon induced great controversy, and much misrepresentation. Few of those who condemned it, read it; and many justified their ignorance of what they detracted, by pretending they could not waste their time upon a volume of theology. This excuse was in reference to its having been printed in quarto, though the sermon itself consists of only about four and twenty pages. The notes are illustrations of a discourse more highly intellectual than most of those who live have heard or read. † [14]

The Spital Sermon derives its name from the priory and hospital of "our blessed Lady, St. Mary Spital," situated on the east side of Bishopsgate-street, with fields in the rear, which now form the suburb, called Spitalfields. This hospital founded in 1197, had a large churchyard with a pulpit cross, from whence it was an ancient custom on Easter Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, for sermons to be preached on the Resurrection before the lord mayor, aldermen, sheriffs, and others who sat in a house of two stories for that purpose; the bishop of London and other prelates being above them. In 1594, the pulpit was taken down and a new one set up, and a large house for the governors and children of Christ's Hospital to sit in.* [15] In April 1559, queen Elizabeth came in great state from St. Mary Spital, attended by a thousand men in harness, with shirts of mail and croslets, and morris pikes, and ten great pieces carried through London unto the court, with drums, flutes, and trumpets sounding, and two morris dancers, and two white bears in a cart.† [16] On Easter Monday, 1617, king James I. having gone to Scotland, the archbishop of Canterbury, the lord keeper Bacon, the bishop of London, and certain other lords of the court and privy counsellors attended the Spital Sermon, with sir John Lemman, the lord mayor, and aldermen; and afterwards rode home and dined with the lord mayor at his house near Billingsgate. ‡ [17] The hospital itself was dissolved under Henry VIII.; the pulpit was broken down during the troubles of Charles I.; and after the restoration, the sermons denominated Spital Sermons were preached at St. Bride's church, Fleet-street, on the three usual days. A writer of the last century * [18] speaks of "a room being crammed as full of company, as St. Bride's church upon the singing a Spittle psalm at Easter, or an anthem on Cicelia's day," but within the last thirty years the Spital Sermons have been removed to Christ church, Newgate-street, where they are attended by the lord mayor, the aldermen, and the governors of Christ's, St. Bartholomew's, St. Thomas's, Bridewell, and Bethlem Hospitals; after the sermon, it is the usage to read a report of the number of children, and other persons maintained and relieved in these establishments. In 1825, the Spital Sermon on Easter Monday was preached by the bishop of Gloucester, and the psalm sung by the children of Christ's Hospital was composed by the rev. Arthur William Trollope, D. D. head classical master. It is customary for the prelate on this occasion, to dine with the lord mayor, sheriffs, and aldermen at the Mansion-house. Hereafter there will be mention of similar invitations to the dignified clergy, when they discourse before the civic authorities. In 1766, bishop Warburton having preached before the corporation, dined with the lord mayor, and was somewhat facetious: "Whether," says Warburton, "I made them wiser than ordinary at Bow (church,) I cannot tell. I certainly made them merrier than ordinary at the Mansion-house; where we were magnificently treated. The lord mayor told me—'The common council were much obliged to me, for that this was the first time he ever heard them prayed for;' I said, 'I considered them as a body who much needed the prayers of the church.'"† [19]

An Easter Tale.

Under this title a provincial paper gives the following detail:— In Roman catholic countries it is a very ancient custom for the preacher to divert his congregation in due season with what is termed a Fabula Paschalis, an Eastern Tale, which was becomingly received by the auditors with peals of Easter laughter. During Lent the good people had mortified themselves, and prayed so much that at length they began to be rather discontented and ill-tempered; so that the clergy deemed it necessary to make a little fun from the pulpit for them and thus give as it were the first impulse towards the revival of mirth and cheerfulness. This practice lasted till the 17th and in many places till the 18th century. Here follows a specimen of one of these tales, extracted from a truly curious volume, the title of which may be thus rendered:— Moral and Religious Journey to Bethlem: consisting of various Sermons for the safe guidance of all strayed, converted, and misled souls, by the Rev. Father ATTANASY, of Dilling. "Christ our Lord was journeying with St. Peter, and had passed through many countries. One day he came to a place where there was no inn, and entered the house of a blacksmith. This man had a wife, who paid the utmost respect to strangers, and treated them with the best that her house would afford. When they were about to depart, our Lord and St. Peter wished her all that was good, and heaven into the bargain. Said the woman, 'Ah! if I do but go to heaven, I care for nothing else.'—'Doubt not,' said St. Peter, 'for it would be contrary to scripture if thou shouldest not go to heaven. Let what will happen, thou must go thither. Open thy mouth. Did I not say so? Why, thou canst not be sent to hell, where there is wailing and gnashing of teeth, for thou hast not a tooth left in thy head. Thou art safe enough; be of good cheer.' Who was so overjoyed as the good woman? Without doubt, she took another cup on the strength of this assurance. But our Lord was desirous to testify his thanks to the man also, and promised to grant him four wishes. 'Well,' said the smith, 'I am heartily obliged to you, and wish that if any one climbs up the pear-tree behind my house, he may not be able to get down again without my leave.' This grieved St. Peter not a little, for he thought that the smith ought rather to have wished for the kingdom of heaven; but our Lord, with his wonted kindness, granted his petition. The smith's next wish was, that if any one sat down upon his anvil, he might not be able to rise without his permission; and the third, that if any one crept into his old flue, he might not have power to get out without his consent. St. Peter said, 'Friend smith, beware what thou dost. These are all wishes that can bring thee no advantage; be wise, and let the remaining one be for everlasting life with the blessed in heaven.' The smith was not to be put out of his way, and thus proceeded: 'My fourth wish is, that my green cap may belong to me for ever, and that whenever I sit down upon it, no power or force may be able to drive me away.' This also received the fiat. Thereupon our Lord went his way with Peter, and the smith lived some years longer with his old woman. At the end of this time grim death appeared, and summoned him to the other world. 'Stop a moment,' said the smith; 'let me just put on a clean shirt, meanwhile you may pick some of the pears on yonder tree.' Death climbed up the tree; but he could not get down again; he was forced to submit to the smith's terms, and promised him a respite of twenty years before he returned. When the twenty years were expired, he again appeared, and commanded him in the name of the Lord and St. Peter to go along with him. Said the smith, 'I know Peter too. Sit down a little on my anvil, for thou must be tired; I will just drink a cup to cheer me, and take leave of my old woman, and be with thee presently. But death could not rise again from his seat, and was obliged to promise the smith another delay of twenty years. When these had elapsed, the devil came, and would fain have dragged the smith away by force. 'Holla, fellow!' said the latter; 'that won't do. I have other letters, and whiter than thou, with thy black carta-bianca. But if thou art such a conjuror as to imagine that thou has any power over me, let us see if thou canst get into this old rusty flue.' No sooner said than the devil slipped onto the flue. The smith and his men put the flue into the fire, then carried it to the anvil, and hammered away at the old-one most unmercifully. He howled, and begged and prayed; and at last promised that he would have nothing to do with the smith to all eternity, if he would but let him go. At length the smith's guardian-angel made his appearance. The business was now serious. He was obliged to go; the angel conducted him to hell. The devil, whom he had so terribly belaboured, was just then attending the gate; he looked out at the little window, but quckly shut it again, and would have nothing to do with the smith. The angel then conducted him to the gate of heaven. St. Peter refused to admit him. 'Let me just peep in, said the smith, 'that I may see how it looks within there.' No sooner was the wicket opened than the smith threw in his cap, and said, 'Thou knowest it is my property, I must go and fetch it.' Then slipping past, he clapped himself down upon it, and said, 'Now I am sitting on my own property; I should like to see who dares drive me away from it.' So the smith got into heaven at last.'* [20]

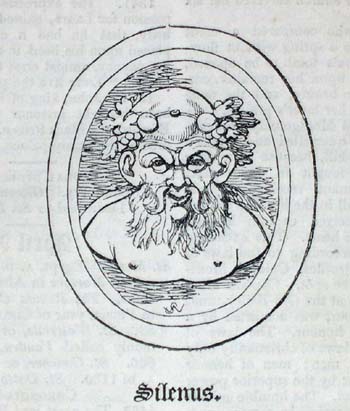

Silenus.

There is a remarkable notice by Dr. E. D. Clarke, the traveller, respecting a custom in the Greek islands. He says, "A circumstance occurs annually at Rhodes which deserves the attention of the literary traveller: it is the ceremony of carrying Silenus in procession at Easter. A troop of boys, crowned with garlands, draw along, in a car, a fat old man, attended with great pomp. I unfortunately missed bearing testimony to this remarkable example, among many others which I have witnessed, of the existence of pagan rites in popular superstitions. I was informed of the fact by Mr. Spurring, a naval architect, who resided at Rhodes, and Mr. Cope, a commissary belonging to the British army; both of whom had seen the procession. The same ceremony also takes place in the island of Scio." It is only necessary here to mention the custom, without adverting to its probable origin. According to ancient fable, Silenus was son to Pan, the god of shepherds and huntsmen; other accounts represent him as the son of Mercury, and foster-father of Bacchus. He is usually described as a tipsey old wine-bibber; and one story of him is, that having lost his way in his cups, and being found by some peasants, they brought him to king Midas, who restored him "to the jolly god" Bacchus, and that Bacchus, grateful for the favour, conferred on Midas the power of turning whatever he touched into gold. Others say that Silenus was a grave philosopher, and Bacchus an enterprising young hero, a sort of Telemachus, who took Silenus for his Mentor and adopted his wise counsels. The engraving is after an etching by Worlidge from a sardonyx gem in the possession of the duke of Devonshire.