APRIL.

Next came fresh April, full of lustyhed,

And wanton as a kid whose horne new buds;

Upon a bull he rode, the same which led

Europa floting through th' Argolick fluds:

His horns were gilden all with golden studs,

And garnished with garlands goodly dight

Of all the fairest flowers and freshest buds

Which th' earth brings forth; and wet he seem'd in sight

With waves, through which he waded for his love's delight.

Spenser.

This is the fourth month of the year. Its Latin name is Aprilis, from aperio, to open or set forth. The Saxons called it, Oster or Eastermonath, in which month, the feast of the Saxon goddess, Eastre, Easter, or Eoster is said to have been celebrated.*[1] April, with us, is sometimes represented as a girl clothed in green, with a garland of myrtle and hawthorn buds; holding in one hand primroses and violets, and in the other the zodiacal sign, Taurus, or the bull, into which constellation the sun enters during this month. The Romans consecrated the first of April to Venus, the goddess of beauty, the mother of love, the queen of laughter, the mistress of the graces; and the Roman widows and virgins assembled in the temple of Virile Fortune, and disclosing their personal deformities, prayed the goddess to conceal them from their husbands.* [2]

In this month the business of creation seems resumed. The vital spark rekindles in dormant existences; and all things "live, and move, and have their being." The earth puts on her livery to await the call of her lord; the air breathes gently on his cheek, and conducts to his ear the warblings of the birds, and the odours of new-born herbs and flowers; the great eye of the world "sees and shines" with bright and gladdening glances; the waters teem with life; man himself feels the revivifying and all-pervading influence; and his

—— spirit holds communion sweet

With the brighter spirits of the sky.

April 1. —All Fools' Day.

St. Hugh, Bp. A.D. 1132. St. Melito, Bp. A.D. 175. St. Gilbert, Bp. of Cathness, A.D. 1240.

On the first of April, 1712, Lord Bolingbroke stated, that in the wars, called the "glorious wars of queen Anne," the duke of Marlborough had not lost a single battle—and yet, that the French had carried their point, the succession to the Spanish monarchy, the pretended cause of these wars. Dean Swift called this statement "a due donation for 'All Fools' Day!'"

On the first of April, 1810, Napoleon married Maria Louisa, archduchess of Austria, on which occasion some of the waggish Parisians called him "un poisson d' Avril," a term which answers to our April fool. On the occasion of his nuptials, Napoleon struck a medal, with Love bearing a thunderbolt for its device.

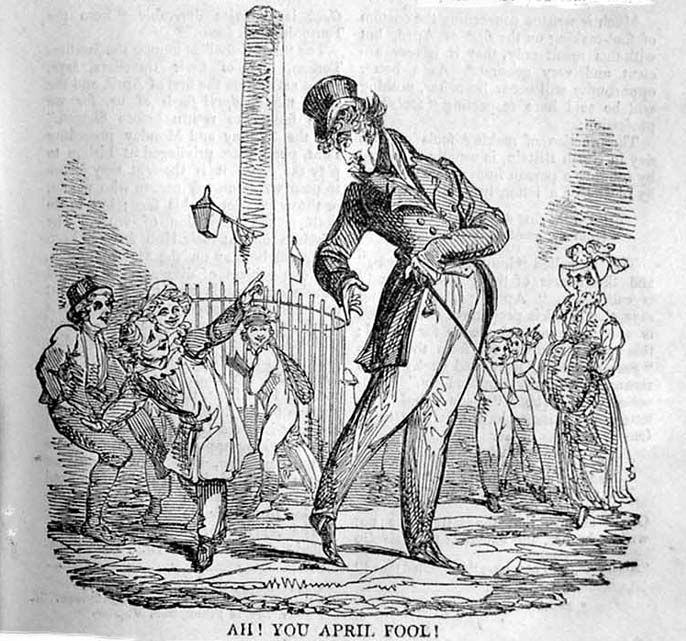

It is customary on this day for boys to practise jocular deceptions. When they succeed, they laugh at the person whom they think they have rendered ridiculous, and exclaim, "Ah! you April fool!"

Thirty years ago, when buckles were worn in shoes, a boy would meet a person in the street with —"Sir, if you please, your shoe's unbuckled," and the moment the accosted individual looked towards his feet, the informant would cry—"Ah! you April fool!" Twenty years ago, when buckles were wholly disused, the urchin-cry was—"Sir, your shoe's untied;" and if the shoe-wearer lowered his eyes, he was hailed, as his buckled predecessor had been, with the said—"Ah! you April fool!" Now, when neither buckles nor strings are worn, because in the year 1825 no decent man "has a shoe to his foot," the waggery of the day is—"Sir, there's something out of your pocket." "Where?" "There!" "What?" "Your hand, sir—Ah! you April fool!"

AH! YOU APRIL FOOL!

Or else some lady is humbly bowed to, and gravely addressed with "Ma'am, I beg your pardon, but you've something on your face!" "Indeed, my man! what is it?" "Your nose, ma'am—Ah! you April fool!"

The tricks that youngsters play off on the first of April are various as their fancies. One, who has yet to know the humours of the day, they send to a cobbler's for a pennyworth of the best "stirrup oil;" the cobbler receives the money, and the novice receives a hearty cut or two from the cobbler's strap: if he does not, at the same time, obtain the information that he is "an April fool," he is sure to be acquainted with it on returning to his companions. The like knowledge is also gained by an errand to some shop for half a pint of "pigeon's milk," or an inquiry at a booksellers for the "Life and Adventures of Eve's Mother."

Then, in-door young ones club their wicked wits,

And almost frighten servants into fits—

"Oh, John! James! John!—oh, quick! oh! Molly, oh!"

Oh, the trap-door! oh, Molly! down below!"

"What, what's the matter!" scream, with wild surprise,

John, James, and Molly, while the young ones' cries

Redouble till they come; then all the boys

Shout "Ah! you April fools!" with clamorous noise;

And little girls enticed down stairs to see,

Stand peeping, clap their hands, and cry "te-hee!"

Each gibing boy escapes a different way,

And meet again some trick, "as good as that," to play. *

Much is written concerning the custom of fool-making on the first of April, but with this result only, that it is very ancient and very general.* [3] As a better opportunity will occur hereafter, nothing will be said here respecting "fools" by profession.

The practice of making fools on this day in North Britain, is usually exercised by sending a person from place to place by means of a letter, in which is written

"On the first day of April

Hunt the gowk another mile."This is called "hunting the gowk;" and the bearer of the "fools' errand" is called an "April gowk." Brand says, that gowk is properly a cuckoo, and is used here metaphorically for a fool; this appears correct; for from the Saxon "geac, a cuckoo," is derived geck, † [4] which means "one easily imposed on." Malvolio, who had been "made a fool" by a letter, purporting to have been written by Olivia, inquires of her

"Why have you suffered me to be—

—Made the most notorious geck and gull

That e'er invention play'd on?"Olivia affirms, that the letter was not written by her, and exclaims to Malvolio

"Alas, poor fool! how have they baffled thee!"

Geck is likewise derivable "from the Teutonic geck, jocus." *[5]

The "April fool" is among the Swedes. Toreen, one of their travellers, says, "We set sail on the first of April, and the wind made April fools of us, for we were forced to return before Shagen." On the Sunday and Monday preceding Lent, people are privileged at Lisbon to play the fool: it is thought very jocose to pour water on any person who passes, or throw powder in his face; but to do both is the perfection of wit.†[6] The Hindoos also at their Huli festival keep a general holiday on the 31st of March, and one subject of diversion is to send people on errands and expeditions that are to end in disappointment, and raise a laugh at the expense of the persons sent. Colonel Pearce says, that "high and low join in it; and," he adds, "the late Suraja Doulah, I am told, was very fond of making Huli fools, though he was a mussulman of the highest rank. They carry the joke here (in India) so far, as to send letters making appointments, in the name of persons, who, it is known, must be absent from their house at the time fixed upon; and the laugh is always in proportion to the trouble given."‡ [7]

The April fool among the French is called "un poisson b Avril." [sic] Their transformation of the term is not well accounted for, but their customs on the day are similar to ours. In one instance a "joke" was carried too far. At Paris, on the 1st of April, 1817, a young lady pocketed a watch in the house of a friend. She was arrested the same day, and taken before the correctional police, when being charged with the fact, she said it was an April trick (un poisson d'Avril.) She was asked whether the watch was in her custody? She denied it; but a messenger was sent to her apartment, and it was found on the chimney-place. Upon which the young lady said, she had made the messenger un poisson d'Avril, "an April fool." The pleasantry, however, did not end so happily, for the young lady was jocularly recommended to remain in the house of correction till the 1st of April, 1818, and then to be discharged as un poisson d' Avril.* [8]

It must not be forgotten, that the practice of "making April fool" in England, is often indulged by persons of maturer years, and in a more agreeable way. There are some verses that pleasantly exemplify this:† [9]

To a LADY, who threatened to make the AUTHOR an APRIL FOOL.

Why strive, dear girl, to make a fool

Of one not wise before,

Yet, having 'scaped from folly's school,

Would fain go there no more?Ah! if I must to school again,

Wilt thou my teacher be?

I'm sure no lesson will be vain

Which thou canst give to me.One of thy kind and gentle looks,

Thy smiles devoid of art,

Avail, beyond all crabbed books,

To regulate my heart.Thou need'st not call some fairy elf,

On any April-day,

To make thy bard forget himself,

Or wander from his way.One thing he never can forget,

Whatever change may be,

The sacred hour when first he met

And fondly gazed on thee.A seed then fell into his breast;

Thy spirit placed it there:

Need I, my Julia, tell the rest?

Thou seest the blossoms here.

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Annual Mercury. Mercurialis annua.

Dedicated to St. Hugh.