February 15.

Sts. Faustinus and Jovita, A.D. 121. St. Sigefride, or Sigfrid, of Sweden, Bp. A.D. 1002.

SHROVE TUESDAY.

It is communicated to the Every-Day Book by a correspondent, Mr. R. N. B—, that at Hoddesdon in Hertfordshire, the old curfew-bell, which was anciently rung in that town for the extinction and relighting of "all fire and candle light" still exists, and has from time immemorial been regularly rang on the morning of Shrove Tuesday at four o'clock, after which hour the inhabitants are at liberty to make and eat pancakes, until the bell rings again at eight o'clock at night. He says, that this custom is observed so closely, that after that hour not a pancake remains in the town.

THE CURFEW.

I hear the far-off curfew sound,

Over some wide-water'd shore,

Swinging slow with sullen roar.Milton.

That the curfew-bell came in with William the Conqueror is a common, but erroneous, supposition. It is true, that by one of his laws he ordered the people to put out their fires and lights, and go to bed, at the eight-o'clock curfew-bell; but Henry says, in his "History of Great Britain," that there is sufficient evidence of the curfew having prevailed in different parts of Europe at that period, as a precaution against fires, which were frequent and fatal, when so many houses were built of wood. It is related too, in Peshall's "History of Oxford," that Alfred the Great ordered the inhabitants of that city to cover their fires on the ringing of the bell at Carfax every night at eight o'clock; "which custom is observed to this day, and the bell as constantly rings at eight as Great Tom tolls at nine." Wherever the curfew is now rung in England, it is usually at four in the morning, and eight in the evening, as at Hoddesdon on Shrove Tuesday.

Concerning the curfew, or the instrument used to cover the fire, there is a communication from the late Mr. Francis Grose, the well remembered antiquary, in the "Antiquarian Repertory" (vol. i.) published by Mr. Ed. Jeffery. Mr. Grose enclosed a letter from the Rev. F. Gostling, author of the "Walk through Canterbury," with a drawing of the utensil, from which an engraving is made in that work, and which is given here on account of its singularity. No other representation of the curfew exists.

"This utensil," says the Antiquarian Repertory, "is called a curfew, or couvre-feu, from its use, which is that of suddenly putting out a fire: the method of applying it was thus;— the wood and embers were raked as close as possible to the back of the hearth, and then the curfew was put over them, the open part placed close to the back of the chimney; by this contrivance, the air being almost totally excluded, the fire was of course extinguished. This curfew is of copper, rivetted together, as solder would have been liable to melt with the heat. It is 10 inches high, 16 inches wide, and 9 inches deep. The Rev. Mr. Gostling, to whom it belongs, says it has been in his family for time immemorial, and was always called the curfew. Some others of this kind are still remaining in Kent and Sussex." It is proper to add to this account, that T. Row, in the "Gentleman's Magazine," because no mention is made "of any particular implement for extinguishing the fire in any writer," is inclined to think "there never was any such." Mr. Fosbroke in the "Encyclopædia of Antiquities" says, "an instrument of copper presumed to have been made for covering the ashes, but of uncertain use, is engraved." It is in one of Mr. F.'s plates.

On T. Row's remark, who is also facetious on the subject, it may be observed, that his inclination to think there never was any such implement, is so far from being warrantable, if the fact be even correct, that it has not been mentioned by any ancient writer, that the fair inference is the converse of T. Row's inclination. Had he consulted "Johnson's Dictionary," he would have found the curfew itself explained as "a cover for a fire; a fire-plate.—Bacon." So that if Johnson is credible, and his citation of authorities is unquestionable, Bacon, no very modern writer, is authority for the fact that there was such an implement as the curfew.

Football at Kingston.

Mr. P., an obliging contributor, furnishes the Every-Day Book with a letter from a Friend, descriptive of a custom on this day in the vicinity of London.

Respected Friend,

Having some business which called me to Kingston-upon-Thames on the day called Shrove Tuesday, I got upon the Hampton-court coach to go there. We had not gone above four miles, when the coachman exclaimed to one of the passengers, "It's Foot-ball day;" not understanding the term, I questioned him what he meant by it; his answer was, that I would see what he meant where I was going.—Upon entering Teddington, I was not a little amused to see all the inhabitants securing the glass of all their front windows from the ground to the roof, some by placing hurdles before them, and some by nailing laths across the frames. At Twickenham, Bushy, and Hampton-wick and Kingston, I had an opportunity of seeing the whole of the custom, which is, to carry a foot-ball from door to door and beg money:—at aboout 12 o'clock the ball is turned loose, and those who can, kick it. In the town of Kingston, all the shops are purposely kept shut upon that day; there were several balls in the town, and of course several parties. I observed some persons of respectability following the ball: the game lasts about four hours, when the parties retire to the public-houses, and spend the money they before collected in refreshments.

I understand the corporation of Kingston attempted to put a stop to this practice, but the judges confirmed the right of the game, and it now legally continues, to the no small annoyance of some of the inhabitants, besides the expense and trouble they are put to in securing all their windows.

I was rather surprised that such a custom should have existed so near London, without my ever before knowing of it.

From thy respected Friend,

N—— S——

Third Month, 1815. J. —— B. ——

Pancakes and Confession.

As fit—as a pancake for Shrove Tuesday.

SHAKSPEARE.

PANCAKE DAY is another name for Shrove Tuesday, from the custom of eating pancakes on this day, still generally observed. A writer in the "Gentleman's Magazine, 1790," says, that "Shrive is an old Saxon word, of which shrove is a corruption, and signifies confession. Hence Shrove Tuesday means Confession Tuesday, on which day all the people in every parish throughout the kingdom, during the Romish times, were obliged to confess their sins, one by one, to their own parish priests, in their own parish churches; and that this might be done the more regularly, the great bell in every parish was rung at ten o'clock, or perhaps sooner, that it might be heard by all. And as the Romish religion has given way to a much better, I mean the protestant religion, yet the custom of ringing the great bell in our ancient parish churches, at least in some of them, still remains, and obtains in and about London the name of Pancake-bell: the usage of dining on pancakes or fritters, and such like provision, still continues." In "Pasquil's Palinodia, 1634," 4to. it is merrily observed that on this day every stomach

till it can hold no more,

Is fritter-filled, as well as heart can wish;

And every man and maide doe take their turne,

And tosse their pancakes up for feare they burne;

And all the kitchen doth with laughter sound,

To see the pancakes fall upon the ground.

Threshing the Hen.

This singular custom is almost obsolete, yet it certainly is practised, even now, in at least one obscure part of the kingdom. A reasonable conjecture concerning its origin is, that the fowl was a delicacy to the labourer, and therefore given to him on this festive day, for sport and food.

At Shrovetide to shroving, go thresh the fat hen,

If blindfold can kill her, then give it thy men.

Maids, fritters and pancakes inough [sic] see you make,

Let slut have one pancake, for company sake.So directs Tusser in his "Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry, 1620," 4to. On this his annotator, "Tusser Redivivus, 1710," (8vo. June, p. 15,) annexes an account of the custom. "The hen is hung at a fellow's back, who has also some horse bells about him the rest of the fellows are blinded, and have boughs in their hands, with which they chase this fellow and his hen about some large court or small enclosure. The fellow with his hen and bells shifting as well as he can, they follow the sound, and sometimes hit him and his hen, other times, if he can get behind one of them, they thresh one another well favour'dly; but the jest is, the maids are to blind the fellows, which they do with their aprons, and the cunning baggages will endear their sweethearts with a peeping-hole, whilst the others look out as sharp to hinder it. After this the hen is boil'd with bacon, and store of pancakes and fritters are made."

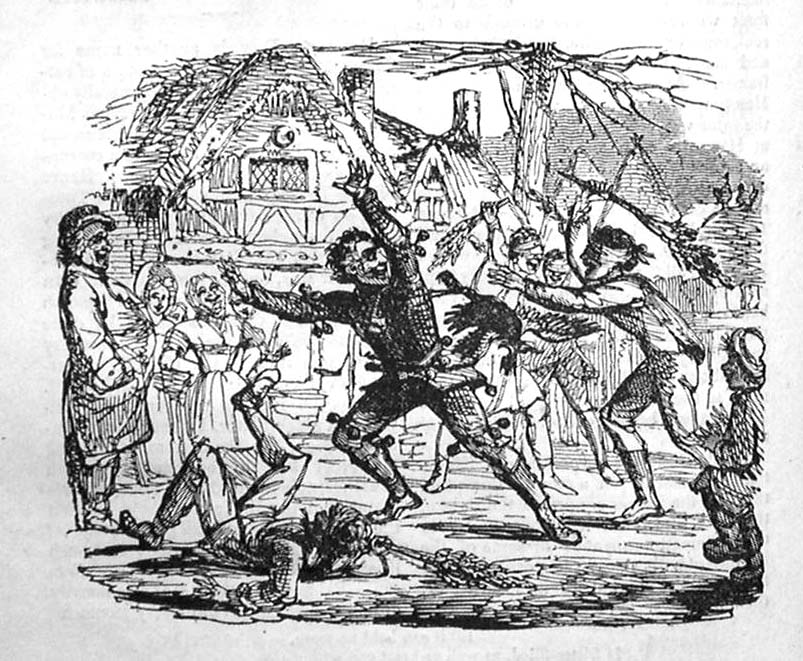

Threshing the Fat Hen at Shrovetide.

Tusser's annotator, "Redivivus," adds, after the hen-threshing. "She that is noted for lying a-bed long, or any other miscarriage, hath the first pancake presented to her, which most commonly falls to the dog's share at last, for no one will own it their due. Thus were youth encourag'd, sham'd, and feasted with very little cost, and always their feasts were accompanied with exercise. The loss of which laudable custom, is one of the benefits we have got by smoking tobacco." Old Tusser himself, by a reference, denotes that this was a sport in Essex and Suffolk. Mr. Brand was informed by a Mr. Jones that, when he was a boy in Wales, the hen that did not lay eggs before Shrove Tuesday was considered useless, and to be on that day threshed by a man with a flail; if he killed her he got her for his pains.

A Hen that spoke on Shrove Tuesday.

On Shrove Tuesday, at a certain ancient borough in Staffordshire, a hen was set up by its owner to be thrown at by himself and his companions, according to the usual custom on that day. This poor hen, after many a severe bang, and many a broken bone, weltering in mire and blood, recovered spirits a little, and to the unspeakable surprise and astonishment of all the company, just as her late master was handling his oaken cudgel to fling at her again, opened her mouth and said—"Hold thy hand a moment, hard-hearted wretch! if it be but out of curiosity, to hear one of my feathered species utter articulate sounds.—What art thou, or any of thy comrades, better than I, though bigger and stronger, and at liberty, while I am tied by the leg? What are thou, I say, that I may not presume to reason with thee, though thou never reasonest with thyself? What have I done to deserve the treatment I have suffered this day, from thee and thy barbarous companions? Whom have I ever injured? Did I ever profane the name of my creator, or give one moment's disquiet to any creature under heaven? or lie, or deceive, or slander, or rob my fellow-creatures? Did I ever guzzle down what should have been for the support and comfort (in effect the blood) of a wife and innocent children, as thou dost every week of thy life? A little of thy superfluous grain, or the sweeping of thy cupboard, and the parings of thy cheese, moistened with the dew of heaven, was all I had, or desired for my support; while, in return, I furnished thy table with dainties. The tender brood, which I hatched with assiduity, and all the anxiety and solicitude of a humane mother, fell a sacrifice to thy gluttony. My new laid eggs enriched thy pancakes, puddings, and custards; and all thy most delicious fare. And I was ready myself, at any time, to lay down my life to support thine, but the third part of a day. Had I been a man, and a hangman, and been commanded by authority to take away thy life for a crime that deserved death, I would have performed my office with reluctance, and with the shortest, and the least pain or insult, to thee possible. How much more if a wise providence had so ordered it, that thou hadst been my proper and delicious food, as I am thine? I speak not this to move thy compassion who hast none for thy own offspring, or for the wife of thy bosom, nor to prolong my own life, which through thy most brutal usage of me, is past recovery, and a burden to me; nor yet to teach thee humanity for the future. I know thee to have neither a head, a heart, nor a hand to show mercy; neither brains, nor bowels, nor grace, to hearken to reason, or to restrain thee from any folly. I appeal from thy cruel and relentless heart to a future judgment; certainly there will be one sometime, when the meanest creature of God shall have justice done it, even against proud and savage man, its lord; and surely our cause will then be heard, since, at present, we have none to judge betwixt us. O, that some good Christian would cause this my first and last speech to be printed, and published through the nation. Perhaps the legislature may not think it beneath them to take our sad case into consideration. Who can tell but some faint remains of common sense among the vulgar themselves, may be excited by a suffering dying fellow-creature's last words, to find out a more good-natured exercise for their youth, than this which hardens their hearts, and taints their morals? But I find myself spent with speaking. And now villain, take good aim, let fly thy truncheon, and despatch at one manly stroke, the remaining life of a miserable mortal, who is utterly unable to resist, or fly from thee." Alas! he heeded not. She sunk down, and died immediately, without another blow. Reader, farewell! but learn compassion towards an innocent creature, that has, at least, as quick a sense of pain as thyself.

This article is extracted from the "Gentleman's Magazine," for the year 1749. It appeals to the feelings and the judgment, and is therefore inserted here, lest one reader should need a dissuasive against the cruelty of torturing a poor animal on Shrove Tuesday.

Hens were formerly thrown at, as cocks are still, in some places.

THROWING AT COCKS.

This brutal practice on Shrove Tuesday is still conspicuuous in several parts of the kingdom. Brand affirms that it was retained in many schools in Scotland within the last century, and he conjectures "perhaps it is still in use:" a little inquiry on his part would have discovered it in English schools. He proceeds to observe, that the Scotch schoolmasters "were said to have presided at the battle, and claimed the run-away cocks, called fugees, as their perquisites." To show the ancient legitimacy of the usage, he instances a petition in 1355, from the scholars of the school of Ramera to their schoolmaster, for a cock he owed them upon Shrove Tuesday, to throw sticks at, according to the usual custom for their sport and entertainment. No decently circumstanced person however rugged his disposition, from neglect in his childhood, will in our times permit one of his sons to take part in this sport. This is a natural consequence of the influence which persons in the higher ranks of life can beneficially exercise. Country gentlemen threw at the poor cock formerly: there is not a country gentleman now who would not discourage the shocking usage.

Strutt says that in some places, it was a common practice to put a cock into an earthen vessel made for the purpose, and to place him in such a position that his head and tail might be exposed to view; the vessel, with the bird in it, was then suspended across the street, about 12 or 13 feet from the ground, to be thrown at by such as chose to make trial of their skill; twopence was paid for four throws, and he who broke the pot, and delivered the cock from his confinement, had him for a reward. At North Walsham, in Norfolk, about 60 years ago, some wags put an owl into one of these vessels; and having procured the head and tail of a dead cock, they placed them in the same position as if they had appertained to a living one; the deception was successful; and at last, a labouring man belonging to the town, after several fruitless attempts, broke the pot, but missed his prize; for the owl being set at liberty, instantly flew away, to his great astonishment, and left him nothing more than the head and tail of the dead bird, with the potsherds, for his money and his trouble; this ridiculous adventure exposed him to the continual laughter of the town's people, and obliged him to quit the place.

Shying at Leaden Cocks.

A correspondent, S. W., says, "It strikes me that the game of pitching at capons, practised by boys when I was young, took its rise from this sport, (the throwing at cocks,) indulged in by the matured barbarians. The capons were leaden representations of cocks and hens pitched at by leaden dumps."

Another correspondent, whose MS. collections are opened to the Every-Day Book, has a similar remark in one of his common-place books, on the sports of boys. He says, "Shying at Cocks.— Probably in imitation of the barbarous custom of 'shying' or throwing at the living animal. The 'cock' was a representation of a bird or a beast, a man, a horse, or some device, with a stand projecting on all sides, but principally behind the figure. These were made of lead cast in moulds. They were shyed at with dumps from a small distance agreed upon by the parties, generally regulated by the size or weight of the dump, and the value of the cock. If the thrower overset or knocked down the cock, he won it; if he failed, he lost his dump.

"Shy for shy.— This was played at by two boys, each having a cock placed at a certain distance, generally about four or five feet asunder, the players standing behind their cocks, and throwing alternately; a bit of stone or wood was generally used to throw with: the cock was won by him who knocked it down. Cocks and dumps were exposed for sale on the butchers' shambles on a small board, and were the perquisite of the apprentices, who made them; and many a pewter plate, and many an ale-house pot, were melted at this season for shying at cocks, which was as soon as fires were lighted in the autumn. These games, and all others among the boys of London, had their particular times or season; and when any game was out, as it was termed, it was lawful to steal the thing played with; this was called smugging and it was expressed by the boys in a doggrel: viz.

"Tops are in. Spin 'em agin.

Tops are out. Smuggin about.or

Tops are in. Spin 'em agin.

Dumps are out, &c."The fair cock was not allowed to have his stand extended behind, more than his height and half as much more, nor much thicker than himself, and he was not to extend in width more than his height, nor to project over the stand; but fraudulent cocks were made extending laterally down sideways, and with a long stand behind; the body of the cock was made thinner, and the stand thicker, by which means the cock bent upon being struck, and it was impossible to knock him over." This information may seem trifling to some, but it will interest many. We all look back with complacency on the amusements of our childhood; and "some future Strutt," a century or two hence, may find this page, and glean from it the important difference between the sports of boys now, and those of our grandchildren's great grandchildren.

Cock-fighting.

The cruelty of cock-fighting was a chief ingredient of the pleasure which intoxicated the people on Shrove Tuesday.

Cock-fighting was practised by the Greeks. Themistocles, when leading his troops against the Persians, saw two cocks fighting, and roused the courage of his soldiers by pointing out the obstinacy with which these animals contended, though they neither fought for their country, their families, nor their liberty. The Persians were defeated; and the Athenians, as a memorial of the victory, and of the incident, ordered annual cock-fighting in the presence of the whole people. Beckmann thinks it existed even earlier. Pliny says cock-fighting was an annual exhibition at Pergamus. Plato laments that not only boys, but men, bred fighting birds, and employed their whole time in similar idle amusements. Beckmann mentions an ancient gem in sir William Hamilton's collection, whereon two cocks are fighting, while a mouse carries away the ear of corn for which they contest: "a happy emblem," says Beckmann, "of our law-suits, in which the greater part of the property in dispute falls to the lawyers." The Greeks obtained their fighting cocks from foreign countries; according to Beckmann, the English import the strongest and best of theirs from abroad, especially from Germany.

Cæsar mentions the English cocks in his "Commentaries;" but the earliest notice of cock-fighting in England is by Fitz-Stephens, who died in 1191. He mentions this as one of the amusements of the Londoners, together with the game of foot-ball. The whole passage is worth transcribing. "Yearly at Shrove-tide, the boys of every school bring fighting-cocks to their masters, and all the forenoon is spent at school, to see the cocks fight together. After dinner, all the youth of the city goeth to play at the ball in the fields; the scholars of every study have their balls; the practisers also of all the trades have every one their ball in their hands. The ancienter sort, the fathers, and the wealthy citizens, come on horseback, to see these youngsters contending at their sport, with whom in a manner they participate by motion; stiffing their own natural heat in the view of the active youth, with whose mirth and liberty they seem to communicate."

Cock-fighting was prohibited in England under Edward III. and Henry VIII., and even later: yet Henry himself indulged his cruel nature by instituting cock-fights, and even James I. took great delight in them; and within our own time, games have been fought, and attendance solicited by public advertisement, at the Royal Cock-pit, Whitehall, which Henry VIII. built.

Beckmann says, that as the cock roused Peter, so it was held an ecclesiastical duty "to call the people to repentance, or at least to church;" and therefore, "in the ages of ignorance, the clergy frequently called themselves the cocks of the Almighty."

Old Shrove-tide Revels.

On Shrove Tuesday, according to an old author, "men ate and drank, and abandoned themselves to every kind of sportive foolery, as if resolved to have their fill of pleasure before they were to die."

The preparing of bacon, meat, and the making of savoury black-puddings, for good cheer after the coming Lent, preceded the day itself, whereon, besides domestic feasting and revelry, with dice and card-playing, there was immensity of mumming. The records of Norwich testify, that in 1440, one John Gladman, who is there called "a man who was ever trewe and feythfull to God and to the kyng" and constantly disportive, made a public disport with his neighbours, crowned as king of christmas, on horseback, having his horse bedizened with tinsel and flauntery, and preceded by the twelve months of the year, each month habited as the season required; after him came Lent, clothed in white and herring-skins, on a horse with trappings of oyster-shells, "in token that sadnesse shulde folowe, and an holy tyme;" and in this sort they rode through the city, accompanied by others in whimsical dresses, "makyng myrth, disportes, and playes." Among much curious observation on these Shrove-tide mummings, in the "Popish Kingdome" it is affirmed, that of all merry-makers,

The chiefest man is he, and one that most deserveth prayse

Among the rest, that can finde out the fondest kinde of playes.

On him they look and gaze upon, and laugh with lustie cheere,

Whom boys do follow, crying foole, and such like other geare.

He in the mean time thinkes himselfe a wondrous worthie man, &c.It is further related, that some of the rout carried staves, or fought in armour; others, disguised as devils, chased all the people they came up with, and frightened the boys: men wore women's clothes, and women, dressed as men, entered their neighbours' or friends' houses; some were apparelled as monks, others arrayed themselves as kings, attended by their guards and royal accompaniments; some disguised as old fools, pretended to sit on nests and hatch young fools; others wearing skins and dresses, became counterfeit bears and wolves, roaring lions, and raging bulls, or walked on high stilts, with wings at their backs, as cranes:

Some like filthy forme of apes, and some like fools are drest,

Which best beseeme those papistes all, that thus keep Bacchus' feast[.]Others are represented as bearers of an unsavoury morsel—

—————that on a cushion soft they lay,

And one there is that, with a flap doth keepe the flies away[.]Some stuffed a doublet and hose with rags or straw—

Whom as a man that lately dyed of honest life and fame,

In blanket did they beare about, and streightways with the same

They hurl him up into the ayre, not suff'ring him to fall,

And this they doe at divers tymes, the citie over all.The Kentish "holly boy," and "ivy girl" are erroneously supposed (at p. 226) to have been carried about on St. Valentine's day. On turning to Brand, who also cites the circumstance, it appears they were carried the Tuesday before Shrove Tuesday, and most probably were the unrecognised remains of the drest mawkin of the "Popish Kingdome," carried about with various devices to represent the "death of good living," and which our catholic neighbours continue. The Morning Chronicle of March the 10th, 1791, represents the peasantry of France carrying it at that time into the villages, collecting money for the "funeral," and, "after sundry absurd mummeries," committing the body to the earth.

Neogeorgus records, that if the snow lay on the ground this day, snow-ball combats were exhibited with great vigour, till one party got the victory, and the other ran away: the confusion whereof troubled him sorely, on account of its disturbance to the "matrone olde," and "sober man," who desired to pass without a cold salutation from the "wanton fellowes."

The "rabble-rout," however, in these processions and mockeries, had the honour of respectable spectators, who seem to have been somewhat affect by the popular epidemic. The same author says that,

————— the noble men, the rich and men of hie degree,

Lest they with common people should not seeme so mad to bee,came abroad in "wagons finely framed before" drawn by "a lustie horse and swift of pace," having trappings on him from head to foot, about whose neck,

———— and every place before,

A hundred gingling belles do hang, to make his courage more,and their wives and children being seated in these "wagons," they

———behinde themselves do stande

Well armde with whips, and holding faste the bridle in their hande.Thus laden and equipped

With all their force throughout the streetes and market place they ron,

As if some whirlwinde mad, or tempest great from skies should come,and thus furiously they drove without stopping for people to get out of their way:

Yea, sometimes legges or arms they breake, and horse and cart and all

They overthrow, with such a force, they in their course do fall!The genteel "wagon"-drivers ceased not with the cessation of the vulgar sports on foot,

But even till midnight holde they on, their pastimes for to make,

Whereby they hinder men of sleepe, and cause their heades to ake

But all this same they care not for, nor do esteeme a boare,

So they may have their pleasure, &c.

APPRENTICES' HOLIDAY.

Shrove Tuesday was until late years the great holiday of the apprentices; why it should have been so is easy to imagine, on recollecting the sports that boys were allowed on that day at school. The indulgencies of the ancient city 'prentices were great, and their licentious disturbances stand recorded in the annals of many a fray. Mixing in every neighbouring brawl to bring it if possible to open riot, they at length assumed to determine on public affairs, and went in bodies with their petitions and remonstrances to the bar of the house of commons, with as much importance as their masters of the corporation. A satire of 1675 says,

They'r mounted high, contemn the humble play

Of trap or foot-ball on a holiday

In Finesbury-fieldes. No, 'tis their brave intent,

Wisely t' advise the king and parliament.But this is not the place to notice their manners further. The successors to their name are of another generation, they have been better educated, live in better times, and having better masters, will make better men. The apprentices whose situation is to be viewed with anxiety, are the out-door apprentices of poor persons, who can scarcely find homes, or who being orphans, leave the factories or work-rooms of the masters, at night, to go where they can, and do what they please, without paternal care, or being the creatures of any one's solicitude, and are yet expected to be, or become good members of society[.]

PANCAKES.

A MS. in the British Museum quoted by Brand states, that in 1560, it was a custom at Eton school on Shrove Tuesday for the cook to fasten a pancake to a crow upon the school door; and as crows usually hatch at this season, the cawing of the young ones for their parent heightened this heartless sport. From a question by Antiquarius, in the "Gentleman's Magazine," 1790, it appears that it is a custom on Shrove Tuesday at Westminster school for the under clerk of the college, preceded by the beadle and the other officers, to throw a large pancake over the bar which divides the upper from the lower school. Brand mentions a similar custom at Eton school. Mr. Fosbroke is decisive in the opinion that pancakes on Shrove Tuesday were taken from the heathen Fornacalia, celebrated on the 18th of February, in memory of making bread, before ovens were invented, by the goddesss Fornax.

FOOT-BALL.

This was, and remains, a game on Shrove Tuesday, in various parts of England.

Sir Frederick Morton Eden in the "Statistical account of Scotland," says that at the parish of Scone, county of Perth, every year on Shrove Tuesday the bachelors and married men drew themselves up at the cross of Scone, on opposite sides; a ball was then thrown up, and they played from two o'clock till sun-set. The game was this: he who at any time got the ball into his hands, run with it till overtaken by one of the opposite part; and then, if he could shake himself loose from those on the opposite side who seized him, he run on; if not, he threw the ball from him, unless it was wrested from him by the other party, but no person was allowed to kick it. The object of the married men was to hang it, that is, to put it three times into a small hole in the moor, which was the dool or limit on the one hand: that of the bachelors was to drown it, or dip it three times in a deep place in the river, the limit on the other: the party who could effect either of these objects won the game; if neither won, the ball was cut into equal parts at sun-set. In the course of the play there was usually some violence between the parties; but it is a proverb in this part of the country that "All is fair at the ball of Scone." Sir Frederick goes on to say, that this custom is supposed to have had its origin in the days of chivalry; when an Italian is reported to have come into this part of the country challenging all the parishes, under a certain penalty in case of declining his challenge. All the parishes declined this challenge except Scone, which beat the foreigner, and in commemoration of this gallant action the game was instituted. Whilst the custom continued, every man in the parish, the genry not excepted, was obliged to turn out and support the side to which he belonged, and the person who neglected to do his part on that occasion was fined; but the custom being attended with certain inconveniences, was abolished a few years before Sir Frederick wrote. He further mentions that on Shrove Tuesday there is a standing match at foot-ball in the parish of Inverness, county of Mid Lothian, between the married and unmarried women, and he states as a remarkable fact that the married women are always successful.

Crowdie is mentioned by sir F. M. Eden, ("State of the Poor,") as a never failing dinner on Shrove Tuesday, with all ranks of people in Scotland, as pancakes are in England; and that a ring is put into the basin or porringer of the unmarried folks, to the finder of which, by fair means, it was an omen of marriage before the rest of the eaters. This practice on Fasten's Eve, is described in Mr. Stewart's "Popular Superstitions of the Highlands," with little difference; only that the ring instead of being in "crowdie" is in "brose," made of the "bree of a good fat jigget of beef or mutton." This with plenty of other good cheer being despatched, the Bannich Junit, or "sauty bannocks" are brought out. They are made of eggs and meal mixed with salt to make the "sauty," and being baked or toasted on the gridiron, "are regarded by old and young as a most delicious treat." They have a "charm" in them which enables the highlander to "spell" out his future: this consists of some article being intermixed in the meal-dough, and he to whom falls the "sauty bannock" which contains it, is sure—if not already married—to be married before the next anniversary. Then the Bannich Brauder, or "dreaming bannocks" find a place. They contain "a little of that substance which chimney-sweeps call soot." In baking them "the baker must be as mute as a stone—one word would destroy the whole concern." Each person has one, slips off quietly to bed, lays his head on his bannock, and expects to see his sweetheart in his sleep.

Shakspeare in King Henry IV. says,

Be merry, be merry, ——

'Tis merry in hall, when beards wag all

And welcome merry Shrovetide.

Be merry, be merry, &c.It is mentioned in the "Shepherd's Almanack" of 1676, that "some say, thunder on Shrove Tuesday foretelleth wind, store of fruit, and plenty. Others affirm that so much as the sun shineth on that day, the like will shine every day in Lent."

FLORAL DIRECTORY.

Cloth of Gold. Crocus sulphurcus.

Dedicated to St. Sigifride.